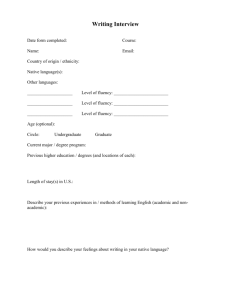

A person (learns, figures out, induces) a general idea (verbal

advertisement

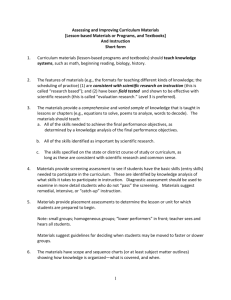

Designing Instruction Phases of Mastery Martin A. Kozloff Copyright 2006 Review We’ve been studying tools for designing instruction. Let’s review them. 1. We find out what our state standard course of study requires us to teach. We add skills and make the wording of standards concrete and clear. 2. We determine what KIND or form of knowledge the standard is: verbal association, concept, rule relationship, cognitive routine. This is important, because the way we communicate information (the way we instruct) depends on the kind of information (form of knowledge) we are trying to communicate. To teach concepts, we present examples. To teach verbal associations, we do not present examples. 3. Then we determine which phase of mastery we are teaching: acquisition (new knowledge; aim for accuracy), fluency (aim for accuracy plus speed), generalization (aim for application to new examples), retention (aim to sustain skill over time). WHAT we teach, HOW we teach, and how we ASSESS learning depends on the phase of mastery we are working on. 4. Now we determine exactly which skills students must learn in order to achieve the curriculum standard. What does someone have to know to DO long division? (a) Some of these are new skills that we will teach. (b) And some of these are pre-skills that students need before we begin the new instruction, so that they can understand and learn from the new instruction. So, we do a TASK ANALYSIS of long division to find out the pre-skills and the steps that we must teach and must review and firm up before we start on long division. 5. Next, we state clear and concrete OBJECTIVES. What will students DO to show whether they have achieved the standard. The objective tells us what students will DO, what we must TEACH, and what we must ASSESS with respect to the phase of mastery. 6. Finally, we select EXAMPLES that will clearly communicate the information---the concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine. 7. Now we know what to teach. So, we can plan the instructional procedure that will effectively communicate the information students need in order to achieve the objective and standard. [Please read that sentence again.] Specifically, we plan how to review prior knowledge and pre-skills; gain attention; how to frame (introduce) the task; how to tell (model) the new information; how to lead students through the new information; how to test/check whether students learned it; how to correct errors, and so on. The first tool we studied was curriculum standards [in “Designing instruction: Curriculum standards”]. We saw how to use scientific research and subject matter experts to add standards to a curriculum, and how to improve poorly worded standards. Then we studied the different forms of knowledge [“Designing instruction: Forms of knowledge”]. Here are the main points you learned regarding forms of knowledge. 1. Experience is of specific things and events. See a dog. Hear music. But knowledge is general. Knowledge is general ideas about how specific things are connected. a. Verbal associations are knowledge of how specific words and things go together. “The dog’s name is Rover.” (simple fact). “Sugar consists of three elements: carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.” (verbal chain) b. Concepts are an idea (far, on, green, government) based on features that are shared by a set of things. The common features are the concept. The name of the concept (“canine”) is NOT the concept. The name is just a way to communicate the concept. 2 c. Rule-relationships are connections between sets of things. For example, “All dogs are canines” is a rule that connects the set of dogs with the set of canines. d. Cognitive routines are sequences of steps (governed by rules) that accomplish something. 2. However, you cannot teach a general idea all by itself. For example, you cannot teach the concept---blue---without SHOWING examples of blue. You cannot teach the cognitive routine for decoding words without using words that show the routine. Without EXAMPLES, instruction is literally empty. 3. You can’t learn a concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine by seeing just one example. Because any one thing has many features. If a teacher holds up a pencil and says, “This is a pencil,” WHAT is pencil? Yellow? Point? Piece of wood? Something with an eraser? Something in the teacher’s hand? In other words, one example does not give precise enough information so that a learner can figure out what it is an example OF. Students are likely to make the WRONG interpretation. 4. Therefore, to learn concepts, rule-relationships, and cognitive routines, the teacher presents several examples that are DIFFERENT in many (unimportant) ways, but are the SAME in the most important way that defines the concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine. For example, the teacher holds up blue squares, blue circles, and blue triangles and calls them all “blue.” Students learn (get, figure out) the general idea (concept--blue) by comparing these examples. They see that they are the same in only one way (color) and they are called the same ONE name (“blue”). Therefore, logically, the one way they are the same (color) MUST be what MAKES them “blue.” Then the teacher juxtaposes examples of blue and nonexamples of blue, and names them. A blue circle. [“This is blue.”] A yellow circle. [“Not blue.”] By CONTRASTING the example and nonexample, the students learn, get, figure out that the one way they are DIFFERENT 3 (color) must logically be what MAKES them different things---“blue” vs. “not blue.” [Don’t worry if you quite don’t get this yet. We will examine how we learn from examples a little later in the course. And you will get it!] 5. Certain elements make it possible to communicate information (e.g., definitions, examples) clearly, so that students learn quickly, without struggling and making lots of errors---which is a huge waste of precious time. The elements include concrete and clear objectives; reviewing background knowledge or pre-skills needed to learn new material; gaining attention; framing the instruction; providing focused instruction (instruction focused on the objective) using model, lead, and immediately testing/checking to see if students learned from the model and lead; error correction; presenting examples and nonexamples; delayed testing/checking (at the end of the instruction) to see if students learned ALL of the examples; and review of instruction. These are organized into what we called a General Procedure for Teaching. However, we add a few elements to the general procedure so that we can effectively communicate each form of knowledge. For instance, to teach concepts, rule-relationships, and cognitive routines, we use examples and nonexamples; and to teach cognitive routines, we also teach the steps. The document “Designing Instruction: Forms of Knowledge,” showed you examples of how to teach each form of knowledge. This document focuses on the next tool for designing instruction--- namely, the phase of mastery we are working on. You see, the objective, the instructional procedure, and the assessment all depend on whether we are working on new knowledge (acquisition); whether we want students to use their new knowledge fluently; whether we want students to generalize their new knowledge; or whether we want students to retain what they learned earlier. [Please read that sentence again.] 4 Four Phases of Mastery You can’t take mastery for granted. Merely going over material won’t do it. You have to pay attention to students getting it right, becoming faster while maintaining accuracy, applying knowledge to new examples, and retaining knowledge over time. Students will not learn these without you. And students with diverse learning needs will fail miserably. I know of cases where a teacher used a reading curriculum with 165 lessons. The class was almost finished. When the teacher tested to see how much students retained, she learned that students had learned almost nothing after lesson 30. So, please pay attention, and learn the simple methods to assess and teach the four phases of mastery. [Please see the table at the end of this document. It summarizes main points in this document.] You’ve probably seen ballroom dancers on TV. Flawless. Their routine goes on for five minutes and they don’t miss a beat; they don’t miss a step. They have mastered the dance. Now imagine they are learning a new one—the bolero. http://www.ballroomdancers.com/Dances/media.asp?Dance=BOL&StepNum=43 6 http://www.ballroomdancing.com.au/photogallery/qldopen2001/index.htm How will they master the bolero? Probably like this. Acquisition Phase First they will learn one step or position. 5 Their teacher will model it for them. They will do it with the teacher (lead). Then they will try it on their own (immediate acquisition test/check). Model. “Watch me…Like this.” Lead. “Try it with me.” Immediate Acquisition Test/check. “Your turn.” If they make any errors, or if they are off a bit (for example, not holding their arms just right), the teacher will correct them. “Like this” (model)… “Now you do it” (test/check) They practice this step or position until they do it the right way—accurately--until they are FIRM. Then they begin to learn the next step in the routine. Maybe the next step is a turn. Notice that the turn builds on the first thing they learned—the starting position. Strategic integration is part of the phase of acquisition. When the dancers have mastered the first step or position, they learn another, and another. Then they learn to assemble these separate steps and positions (elements) into a longer ROUTINE. This is called “strategic integration.” For example, they begin in the start position; then they move across the dance floor turning a few times; then the female partner bends to the side; then she straightens up and they twirl a few times. That is a little routine that is part of their whole performance. The little routine integrates of the elementary steps and positions that they learned. Just as when students are learning 6 long division, sounding out words, or writing essays (routines consisting of steps), the dancers practice the routine until they “have it down”---they don’t make mistakes. As the days go by, they learn more new steps and add them to the routine sequence, until finally (through practice) they have integrated all the steps into a five minute performance. This is the same as students learning to read words, and then read sentences, and then read whole paragraphs. 7 Independence. Independence is another aspect of acquisition of new knowledge. At first, the dancers receive a lot of assistance from their teacher—live, video, diagrams in a book. But as the dancers acquire the skills (that is, as they become more accurate), the teacher FADES OUT the assistance, until the dancers can perform (first, each step; then each little routine; and finally the whole performance) by themselves. In summary, in the phase of acquisition, 1. The teacher may be teaching single skills or knowledge only (such as a simple fact or a concept or a rule-relationship in history); or the teacher may be teaching the ELEMENTS of what WILL BE a routine. For example, she will teach students to strategically integrate the elementary facts, concepts, and rule-relationships into an essay on an historical period. Just as the routine for doing long division integrates elementary skills such as estimation, multiplication, writing numbers, and subtracting, so the routine for writing an essay integrates the facts, concepts, and rulerelationships students have learned. [Please read that sentence again] 2. The goal is accuracy. 3. Gradually, the teacher fades assistance as students become more consistently accurate, to build independence. Fluency Let’s say the dancers are (1) learning a new step (acquisition phase for the new step), or (2) working on strategically integrating steps INTO a sequence---a routine. They practice, identify weak spots, firm up the weak spots, and practice some more. The more they practice and firm up their skills, the more automatic the step or routine becomes. They no longer have to guide themselves with reminders (“Head high.) or by counting “One..two…three…fast…fast…one…two…three…fast…fast.” Their steps and the routine become more graceful—much like little kids reading more smoothly. And they do the routine faster and faster because they no longer are slowed down by errors and by thinking about what they are doing. 8 Generalization The dancers borrow from earlier steps and routines to do new steps and routines. For example, the dancers use (apply) the first position they learned to a later step in the routine. This is called generalization, transfer, or application. The dancers apply something they learned earlier to a new situation. “Okay, in this new step we hold our heads and arms the same way we do when we start.” Likewise, when students know the routine for writing essays (learned from performing three earlier examples of the essay-writing routine), they apply (generalize) the routine to different topics. Retention Imagine that every time the dancers learn a new step or routine, they forget or become sloppy with the earlier ones. By the end of their course of instruction, the only thing they’d be able to do (remember) would be the last thing they learned. This often happens in schools, especially with students who have diverse learning needs. Why is there little retention of what was learned? The answer is: 1. The students’ knowledge wasn’t firm, but the teacher moved ahead to new material. For instance, the teacher didn’t use an effective 9 instructional procedure, such as the General Procedure for Teaching. Therefore, some students had no idea what the teacher was talking about. Other students “sort of” got it, but soon forgot it. And other students “got it” but still made errors. 2. Memory naturally decays as time goes by, especially if you don’t regularly USE what you learned. The teacher did not schedule frequent cumulative review and practice. 3. New material interferes with remembering and properly using earlier material. For example, if a teacher first teaches the sound that goes with the letter d, and soon after teaches the sound that goes with the letter b, some students will confuse the two. Instruction is almost completely wasted if there is little retention. Are students going to pay attention and try hard if they know they will soon forget it all? Are teachers going to work hard if they know that students will forget it all? Of course not. There are four ways to retain skill: 1. Make sure students are firm (100% correct) in the phase of mastery when learning a new verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine---before you teach something new. How do you know they are firm? You assess their knowledge. You’ll see how in a minute. 2. Schedule frequent cumulative review and practice. 3. Have students apply or generalize their knowledge. This is another way to practice it. For example, students will remember the definitions of different figures of speech (metaphor, alliteration) if they USE these to write poems. 4. Separate instruction on material that could be confusing---metaphor and simile, mitosis and meiosis. Very important!! There are assessments for every phase of mastery. Basically, what do students know before you begin instruction on that phase; what are they learning during instruction on that phase; and what did they learn by the end of instruction on that phase? You must USE assessment 10 information to make decisions. Is the class overall (and especially your diverse learners) “ready” to learn new material? Are some students weak on pre-skills, or not making satisfactory progress? Is the whole class, or are certain students, forgetting what you taught them? If students DON’T have the pre-skills, or are not making adequate progress, or have not learned or retained enough by the end of instruction (e.g., the end of a unit), then you must determine whether: 1. Your curriculum materials are not adequate. For example, they do not teach a wide enough range of examples for students to learn concepts. 2. Your instructional design is weak. For example, your objectives are not clear enough that you know what to teach. 3. Your instructional delivery is weak in spots. For example, you do not correct errors immediately or well enough. 4. Your students merely need to have errors corrected, or they need “partfirming” (basically, reteaching a chunk of a task), or they need reteaching, or they need intensive instruction. All of this is discussed in the document, “Four level procedure for remediation.” Let’s look at each phase of mastery. What it is. How to teach it. How to assess it. Acquisition Phase Definition of Acquisition In acquisition, the student learns (figures out, induces) a new verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine from the set of examples---called an acquisition set (and perhaps nonexamples) presented and described. Instruction must focus precisely on the objective. Communication (examples, descriptions) must clearly reveal the verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or steps in the cognitive routine. The General Procedure for Teaching (e.g., reviewing pre-skills, gaining attention, framing the new task, 11 modeling the information, etc.) is one way of delivering focused and effective instruction. Objectives or Aims for Acquisition What does it look like when students “get” or learn a new verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine? They USE IT ACCURATELY, or CORRECTLY. The percentage of correct responses is close to 100. For example, the teacher holds up cards. Each one has a letter on it whose sound the teacher taught during the lesson. The teacher says “What sound?” Almost every student gets every one right. The 100% correct rule is crucial! If students are not FIRM on what you have just taught, how can you go on to next things to teach—especially if the next things require skill at the earlier? For example, how can students learn the next skill---sounding out the new words sun, fun, and run---if students are not 100 percent accurate at saying sss when they see s, fff when they see f, rrr when they see r, and uhhh when they see u? How can they sound out words if they are not firm on what the letters say? How can students multiply two-digit numbers if they are not firm on one-digit multiplication? How can they analyze an historical document if they don’t know what the words in it mean? What happens when you add another layer of bricks to a wall whose lower layers are weak? Assessment of Acquisition Assessment happens at three different times: before (pre-instruction), during instruction (progress monitoring), and at the end of instruction on new material (post-instruction or outcome). Let’s say acquisition instruction is on two-digit multiplication. The teacher will use an acquisition set of examples of two-digit multiplication to reveal the common steps in the routine. Pre-instruction Assessment Do students know the pre-skills or elements of two-digit multiplication: counting, writing numbers, renaming, multiplication facts? If so, they are ready to learn two-digit multiplication. If not, the teacher must firm up or even reteach these elements. [This is discussed in the document, “Four level procedure for remediation.”] 12 Progress monitoring or During-instruction Assessment When the teacher models and then leads students through each example of two-digit multiplication, the teacher immediately has students do it on their own. This is an immediate acquisition test. If they make an error, she corrects it by modeling it again, leading them through it, and testing. If and when they do the example correctly, the teacher goes on to the next example. Post-instruction or Outcome Assessment Post-instruction or outcome assessment can be (1) at the end of a lesson; (2) at the end of a unit (series of lessons on the same topic and with the same objective); or better (3) both. Lesson 1 and Test Lesson 2 and Test Lesson 3 and Test Lesson 4, end of unit, and Comprehensive Test. By the end of a lesson the teacher has modeled, led students through, and tested/checked to see whether students can do each example problem on their own. Now the teacher presents ALL of the SAME problems to see if students can do them all, on their own. This is a delayed acquisition test. If any student makes an error, the teacher immediately corrects it (directing the correction to the whole class) with the model, lead, test/check procedure. The teacher knows that she must review these problems before the next lesson. And perhaps she must provide reteaching to some students. It is also post-instruction or outcome assessment if the teacher tests/checks learning after a number of lessons (e.g., a unit) that focused on a objective. For example, 13 1. Students might write an essay describing the main disputes in the writing of the U.S. Constitution, in which they use all of the concepts, dates, political philosophies, persons, and events they were taught. 2. The teacher makes up an exam that asks questions about the concepts, dates, political philosophies, persons, and events they were taught. Most assessment should be connected directly to what you are teaching. That is, you assess students on what you will teach, what you are teaching, and what you just finished teaching. Sometimes this is called “curriculum based measurement” or CBM. Here is an excerpt from Curriculum-based measurement: A manual for teachers, at http://www.jimwrightonline.com/pdfdocs/cbaManual.pdf [Italics added for emphasis.] Curriculum-based measurement, or CBM, is a method of monitoring student educational progress through direct assessment of academic skills. CBM can be used to measure basic skills in reading, mathematics, spelling, and written expression. It can also be used to monitor readiness skills. When using CBM, the instructor gives the student brief, timed samples, or "probes," made up of academic material taken from the child's school curriculum. These CBM probes are given under standardized conditions. For example, the instructor will read the same directions every time that he or she gives a certain type of CBM probe. CBM probes are timed and may last from 1 to 5 minutes, depending on the skill being measured. The child's performance on a CBM probe is scored for speed, or fluency, and for accuracy of performance. Since CBM probes are quick to administer and simple to score, they can be given repeatedly (for example, twice per week). The results are then charted to offer the instructor a visual record of a targeted child's rate of academic progress. 14 Assessment of students’ acquisition of knowledge can also be provided by validated, standardized instruments. However, these do not measure students’ proficiency with the same examples that you used during instruction. They measure the more general skill. You can find examples of reading assessments here http://idea.uoregon.edu/assessment/analysis_results/assess_results_by_test.html Let’s look at examples of the pre-instruction, during-instruction, and postinstruction assessment during acquisition. Pre-instruction assessment. Pre-instruction assessment tells you what students already know or do not know so you can plan instruction; for example, which letter-sounds to start with; how much to review. You can also use pre-instruction assessment to create temporary homogeneous groups so that students who are at the same spot in a curriculum are taught exactly what they are ready to learn. Let’s say you are a first grade teacher. It’s the first week of school. Your state and district standard course of study tells you to begin teaching students to sound out words. Decoding and Word Recognition 1.10 Generate the sounds from all the letters and letter patterns [lettersound correspondence. f says fff], including consonant blends and longand short-vowel patterns (i.e., phonograms), and blend those sounds into recognizable words. http://www.cde.ca.gov/be/st/ss/enggrade1.asp However, students can’t sound out (blend sounds into) words if they are not firm on letter-sound correspondence, because letter-sound correspondence is an element or part or pre-skill of sounding out. Therefore, you give a preinstruction assessment of letter-sound knowledge. For example, you have cards. Each card has a letter (a , s, m, i, t) or a blend (br, st, fl). You also have a sheet of paper that lists all the sounds and blends, and has three columns to score students’ responses. You hold up each card, and say, “Boys and girls, what sound?” You mark the sheet after each sound or blend. When 15 you are finished, you know that a few students need extra practice (firming up) on certain letter-sounds. You also know which sounds and blends require more than extra practice (firming up), but need beginning instruction (on acquisition). Pre-instruction Assessment of Letter-sound Correspondence All students were correct a m s t Only a few students made errors Many students Preparation made errors x x x x e x d x i x f x Review Review Review Teach these students Teach these students Teach the whole class Teach the whole class Teach the whole class You could also test each student individually, using the same method. This would enable you to track the progress of each student, by giving the same assessment every few weeks. You should conduct pre-instruction assessments in almost every subject you teach. For instance, 1. Before teaching long division, pre-test students on the elements or preskills of long division: estimation (27 goes into 110 how many times?); multiplication; addition. This tells you which skills are firm; which skills need a bit of review and firming; and which skills (or which students) need reteaching or initial instruction (acquisition). [Please skim the document “Four-level procedure for remediation.”] 16 2. Before beginning the first chapter in a second semester algebra course, pre-assess students to determine what they have retained (or forgotten) from the first semester. Again, this tells you which skills are firm; which skills need a bit of review and firming; and which skills (or which students) need reteaching or initial instruction (acquisition). 3, Before second semester Spanish, pre-assess students on what they have retained (or forgotten) from the first semester: pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary. Again, this tells you which skills are firm; which skills need a bit of review and firming; and which skills (or which students) need reteaching or initial instruction (acquisition). 4. Before starting material in physics, pre-assess students on the math preskills they will need. Again, this tells you which skills are firm; which skills need a bit of review and firming; and which skills (or which students) need reteaching or initial instruction (acquisition). 5. Before starting second semester U.S. history, pre-assess students on concepts (federalism, representative democracy, checks and balances, manifest destiny), events, persons, and processes (e.g., elections, industrialization, how bills become law), that are needed to learn the new material. This tells you which skills are firm; which skills need a bit of review and firming; and which skills (or which students) need reteaching or initial instruction (acquisition). During-instruction, or progress assessment. During-instruction (or progress-monitoring) assessment tells you how much students are learning as you teach. You don’t want to keep going if they aren’t getting it! For example, you just told (modeled) the verbal definition of the concept mitosis (cell division). Teacher. http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/VL/GG/mitosis.html “Boys and girls. New concept.” [writes mitosis on the board.] “Spell mitosis.” 17 Class. “m i t o s i s” Teacher. “Yes, mitosis.” Teacher. “Get ready to write the definition on your note cards. Mitosis is a process of cell division which results in the production of two daughter cells from a single parent cell. The daughter cells are identical to one another and to the parent cell.” [Model] [Teacher repeats the definition.] Teacher. “Say the definition of mitosis with me…” [Lead] Teacher/ “Mitosis is a process of cell division which results in the Class production of two daughter cells from a single parent cell. The daughter cells are identical to one another and to the parent cell.” Now you give an immediate acquisition test/check (to monitor progress) to see if students learned (and correctly wrote) the definition. Teacher. “Your turn. Define mitosis.” Class. “Mitosis is a process of cell division which results in the production of two daughter cells from a single parent cell.” This progress assessment (immediate acquisition test/check) tells you (1) whether students are firm on the definition, and so you can go on to the next task (e.g., identifying the phases of mitosis); or (2) whether students are not firm, and so you should go back and reteach the definition. Post-instruction, or outcome assessment. Post-instruction, or outcome, assessment tells you how much of the new material students learned in a lesson. Therefore, it tells you whether they achieved the curriculum standard or instructional objective. Let’s start with a simple example of postinstruction, or outcome assessment---a delayed acquisition test. 18 Outcome assessment of sounding out new words. You taught students to sound our six new words. fun sun run ran man fan. Here is the procedure you used. Teacher. ma n o--------> “Listen. mmaann Teacher/ man.” [Model] “Read it with me. mmmaaannn. man.” [Lead] Class. Teacher. “Your turn.” [Immediate acquisition or progressmonitoring test] Class. “mmmaaannn man.” Teacher. “Yes, man!” [Verification] At the end of the lesson, point to each word and have students READ THEM ALL. This is the delayed acquisition test---outcome or post-instruction assessment. 1. Put all the words on the board (or on cards). 2. Point to each word. 3. Say, “What word?” 4. Correct any errors with the model, lead, test, verification procedure. “That word is man.” “Say it with me.” man “What word?” man “Yes, man.” 5. This tells you which words you need to firm up or even reteach. [See the document, “Four level procedure for remediation.] Outcome assessment of learning a new concept. Here’s another example. You have taught students the definition of granite---both the verbal definition and examples/nonexamples. How do you test the outcome of instruction? Simple, give a delayed acquisition test. 19 1. Show the examples and the nonexamples one by one. 2. Ask, “Is this granite?” 3. When students answer, ask a follow up question. “How do you know?” This requires them to use the definition. 4. Correct any errors. Outcome assessment of learning several new concepts. Let’s say you taught five new vocabulary words (concepts) during today’s history lesson. Federalism. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/federalism/ Federalist. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h375.html Anti-federalist. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h374.html Representative democracy. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Representative_democracy Tyranny. http://dictionary.laborlawtalk.com/tyranny You taught these definitions using the General Procedure for Teaching. [Please review the procedure for teaching higher-order concepts in the document, “Designing Instruction: Forms of Knowledge,” before you go on.] Teacher. “Boys and girls. New concept. Tyranny. [Write tyranny on the board.] Spell tyranny.” Class. “t y r a n n y” Teacher. “Yes, tyranny. Get ready to write the definition of tyranny on your note cards.” [Check to see if ready.] Teacher. “Tyranny is a form of government in which the ruler is an absolute dictator not restricted by a constitution or laws or opposition.” “Got that?” [Repeat definition.] Teacher. “Say it with me.” [If the class is now skilled at listening, writing, and remembering, the teacher can TRY to fade out the Lead step.] 20 Teacher/ “Tyranny is a form of government in which the ruler is an Class. absolute dictator not restricted by a constitution or laws or opposition.” Teacher. “Your turn. What is the definition of tyranny?” [Immediate acquisition test/check. Progress-monitoring.] [Now---to illustrate the verbal definition---you present examples and nonexamples of tyranny one after another and label each one. “This is tyranny…. Notice its features from the definition….. This is NOT tyranny. Notice the features it does NOT have.” Teach each new concept the same way.] After you have taught all the new concepts, you give a delayed acquisition test to assess the outcome of the instruction. Use the SAME examples and nonexamples that you used during instruction. Teacher. “Class. Let’s review all of our new concepts.” “Representative democracy. What is the verbal definition?” Class. “Representative democracy is a form of democracy founded on the exercise of popular sovereignty by the people's representatives.” Teacher. “Excellent stating the definition of representative democracy. Teacher. Okay, here’s a political system. You tell me if it is a representative democracy. Ancient Sparta. At the top was a dual monarchy: two kings. Below the monarchy was a council composed of the two kings and twenty-eight nobles who created laws and foreign policy. There was also an assembly of all the high ranking males, called the Spartiate. They elected the council and approved or vetoed proposals from the council. But above them all was a group of five men who led the council, military, educational system, and could veto anything from the 21 council or assembly of Spartiates—the ephores. They could even depose the king.” [Adapted from http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/GREECE/SPARTA.HTM] Class. “It has some features of representative democracy--the Spartiate assembly. But it is also a monarchy.” Teacher. “Good use of the definition. Ancient Sparta was not a representative democracy. It was a mixed type of government.” [The teacher than tests all of the other new concepts—democracy, tyranny, federalism, etc.] Note. This delayed acquisition test/check, outcome assessment, or postinstruction assessment uses the same examples and nonexamples that were presented during acquisition instruction. If you use different examples, you are not testing exactly what you taught. You are testing generalization of knowledge to new examples. Instruction During the Phase of Acquisition. It’s essential that instruction during the phase of acquisition is effective. All students must learn the material to 100% accuracy. How do you design and deliver instruction during the phase of acquisition to ensure that all students learn to the point of 100% accuracy? The answer is, Use the General Procedure for Teaching. Please review examples of the General Procedure in the document, “Designing instruction: Forms of Knowledge.” Notice how the General Procedure (modified slightly depending on whether you are teaching a verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine) pays attention to every detail: students are attending to the right thing; students know what to expect; the set of examples clearly reveals the essential information (e.g., the minerals in granite); students are shown again and again, and led through the examples; every error is corrected; everything taught is checked to see if students learned it. 22 Fluency Definition of Fluency A person whose skill is fluent no longer has to think about what he or she is doing. 67 x23 “Let’s see. First I multiply the numbers in the ones column. That’s 7 and 3. 7 times 3 is 21. I write 1 and carry the 2….” When a person is fluent, knowledge (of a verbal association, concept, rulerelationship, or cognitive routine) is internalized, or covertized; it is automatic. The time between steps is shorter; the person makes fewer errors; therefore, the person applies the knowledge faster and more smoothly. For example, students read word lists, read connected text, define concepts, solve math problems, conduct lab experiments, and analyze poems accurately (they do it right) and quickly. Objectives or Aims for Fluency The objective or aim for the phase of fluency is accurate (or correct) plus quick and smooth (no gaps and hesitations) performance. Research has determined useful fluency aims or benchmarks for different reading skills. For example, 23 http://reading.uoregon.edu/flu/flu_cm_1.php http://reading.uoregon.edu/flu/flu_cm_2.php http://reading.uoregon.edu/flu/flu_cm_3.php So, the benchmark fluency objectives for word reading are: end of grade 1, 60 words correct per minute; end of grade 2, 90-100 words correct per minute; and end of grade 3, 120 words correct per minute. Assessment of Fluency As with acquisition, you should assess fluency before, during, and at the end of fluency instruction on a certain skill. Here are some examples of the skills whose fluency you would want to increase: 24 1. Saying the sounds that go with letters. “What sound?”… rrr. 2. Reading words from a list. 3. Reading connected text: sentences in paragraphs. 4. Writing letters of the alphabet. 5. Identifying and correcting spelling errors in a prepared text. 6. Writing numbers. 7. Addition, subtraction, and multiplication facts. 6 26 7 +3 -12 x4 8. Multi-digit multiplication. 9. Long division. 10. Operations with fractions and percentages. 11. Algebra operations. (12 + 2) (16 -5) Calculating slope Solving equations. 12. Determining distances on a map. 13. Finding locations on a map, given latitude and longitude. 14. Circling examples of metaphors, given examples of different figures of speech. 15. Sorting or identifying samples: rocks, fungi, trees. 16. Anything else you are teaching that students ought to do more quickly. Building fluency for a particular skill takes time. One way to assess fluency over time—from pre-instruction on fluency, through progress on fluency, to outcome of fluency instruction—is with a graph. Each student has his or her own graph for the fluency target. You can even establish an outcome fluency aim with the students. For example, 60 words correct per minute by the end of the year with your first graders. (See the table above.) The class has just learned how to read connected text in story books (acquisition phase of this skill). 25 The cat ran and ran. It ran fast. The cat can see a rat. The rat can see the cat. The rat was sad. Students read the above text accurately, but they read slowly—stopping between words, and sounding out some of the words. You continue teaching new words and sentences, AND you teach them to read the above story more fluently. Here’s how you might assess fluency. 1. Assess each student’s rate and accuracy before you begin fluency instruction. Use a story whose words they can accurately decode. 2. Have each student read for one minute. 3. Mark on your copy of the story each time a student makes an error--reads a word incorrectly or adds a word that isn’t there. Count the same word error (e.g., rans) only once. 4. Count how many words the student read correctly in a minute. And count how many total errors the student made. 5. Plot these numbers on the student’s graph, and help the student to do this. 6. Every week, repeat the assessment (progress assessment), and plot the number correct and the number of errors on the graph. Naturally, students will be reading new stories; so, draw a vertical line on the graph. 7. At the end of the year, assess the student’s outcome fluency. Of course, each next story will have new and longer words. It might look like this. 26 Stories 80 First | New 2 | New 3 | New 4 | Final New | 75 | | | | | 70 | | | | | 65 | | | Objective * 60 Words 55 | | | Correct 50 | | | Per 45 | | Minute 40 | | (* *) 35 | 30 * | Total 25 Errors 20 (+ +) 15 10 ** + | | | |* | | | | | | | |* | | | | | | | | | | + + | | | | * * + + |+ + | + + + + 4 5 6 7 * * |* ++ | 123 | | | * | * * |* * * * * | |+ + + + | + + 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Weeks The graph shows that each time you added a new story, the student’s accuracy and/or speed decreased, but with repeated reading (one way to build fluency), errors decreased and speed increased. Was your fluency-building instruction effective? Yes. The student reached the outcome aim or objective. If students are NOT making adequate progress (for example, the errors do not decrease, or speed does not increase) you have to look closely at HOW they are reading? Are they weak on letter-sound correspondence? If so, reteach this. Are they weak on reading whole words (e.g., they are still sounding them out 27 rather than saying them fast)? Then firm this skill through practice sessions. [See the document entitled, “Four level procedure for remediation.”] You can do the same thing in other subjects. How many math problems, spelling errors corrected, numbers written, letters written, concepts defined, rocks correctly sorted per minute? Sometimes these fluency assessments are part of fluency instruction itself. For example, students do short “speed drills” (for instance, using math worksheets) to build fluency, and you and the students count and graph the number correct per minute and the number of errors. Instruction During the Phase of Fluency Building There are several ways to build fluency: modeling, special cues, and practice. 1. Modeling. The teacher demonstrates what fluent (quicker and smoother, and accurate) performance look like, and then gives students a chance to do it. Sometimes, the teacher adds little rules or reminders as she does this. Here are examples. [This is a phonemic awareness skill.] Teacher. “Boys and girls. Listen. foot…ball. I can say it fast. football.” Teacher. “Listen. foot…ball. Say it fast!!” Class. “football!!” [This is an alphabetic principle, or phonics, skill.] Teacher. “Boys and girls. First I’ll sound out a word. Then I’ll say it fast. Here I go. run o-------> [Teacher moves her finger slowly under each letter.] “rrrruuunnn.” “I can say it fast.” [Teacher moves her finger quickly under the word.] 28 “run” Teacher. “Your turn. First you’ll sound it out. Then you’ll say it fast. Get ready.” run o-------> [Teacher moves her finger slowly under each letter.] Class. “rrruuunnn” Teacher. “Say it fast!” run o-------> [Teacher moves her finger quickly under the word.] Class. “run!” Likewise, the teacher can model how to perform the routine for multiplication and division, reading sentences, calculating the slope, and other skills more quickly, and then have students do it. 2. Special Cues. The faster the conductor waves the baton, the faster the orchestra plays. Likewise, the teacher can use special cues that provide a tempo for the students’ performance. For example, there is a list of words on the board. run runs buns sock socks docks flocks flip slip slips slipped 29 The teacher says, “”Let’s read all these words the fast way. Try not to make mistakes. The error limit is two.” The teacher points to the top word… Teacher. “First word. What word?” Class. “run.” Teacher . (moves down and points to runs.) “Next word. What word?” Class. “runs.” Teacher. (moves down and points to buns) “Next word. What word?” Class. “buns.” Etc. Teacher. “Oh, you are such fast readers. But we can do it EVEN faster. Here we go.” Next, the teacher moves down the list faster. She barely stops between words. Also, the teacher shortens the signal. Instead of “Next word. What word?” the teacher simply moves her finger down to the next word and says “Word?” With practice every day, students will become very fast readers of word lists. The teacher can also use special cues to help students become fluent at reading connected text. For example, students have already learned to track under each word and then say it. The question is how to move them from one word to the next faster. The teacher does this by clapping before each word. Teacher. “When I clap, you say the word. Then move your finger to the next word. Get ready.” Class. “The…cat…ran…and…ran…She…was…a…fast…cat.” [When students are skilled at following the teacher’s cue or signal, the teacher speeds it up.] “The.cat.ran.and.ran…She.was.a.fast.cat.” 30 3. Practice. We already spoke of practice. Repetition. One kind of practice is simply repetition. For example, students read a passage once (and the teacher corrects every error). They read it again (the teacher corrects every error). And once more (the teacher corrects every error). Or, students conjugate a French verb once, twice, and one more time. Or they say all the phases of mitosis once, again, and once more. Or the teacher says the number of the amendment in the Bill of Rights (“First Amendment.”) and students say the rights that are protected (speech, religion, assembly, petition). http://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/constitution.billofrights.html The class does this again. And one last time. Speed drills. Practice can also be in the form of short speed drills or sprints. These should only be for 1 to 3 minutes. Here are examples. “Okay, here’s a page with 15 misspelled words. Circle each misspelled word and correct it. I want you to get at least 12. Get ready? GO!” [Afterwards, the class goes over the page and checks work. If done every few days, students will become fluent at spelling and at checking.] “Here’s a math worksheet. There are 30 multiplication facts. Do them quickly but try not to make errors. Think. Check your answer. You have two minutes. GO!” [Afterwards, the class checks work. The teacher notes which students made more than a few accidental errors. These students may need more practice on accuracy.] Remember that students can also have their own graphs of fluency drills on, for example, math problems correctly solved per minute and words read correctly per minute. Aside from the teacher working with each student, students can do this in pairs. One student reads and the partner follows along and marks errors on his or her own copy of the text. Then the partners review the text and correct errors. Then the partners graph 31 the number of words correctly read and the number of errors. And then they switch roles of reader and checker. Generalization Definition of Generalization Let’s say that during the phase of acquisition you used five examples of conifers to reveal the features that define the general idea (concept) of conifer. Giant Sequoia Juniper Red Cedar Spruce Fir And let’s say that during the phase of acquisition you used five examples of poems so that students learned the steps in the general cognitive routine for analyzing poems. The point of using examples is not ONLY that students learn these examples (e.g., what a Giant Sequoia looks like), but that they learn the general idea (concept, cognitive routine) revealed by the examples, so that that they can apply the knowledge gained from the examples to new examples. Generalization is the application or transfer of knowledge to new examples. Objectives or Aims for Generalization The objectives or aims are straightforward. Once students have learned a concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine, they properly apply this knowledge to examples they have not seen. They sound out new words, analyze new poems, multiply new two-digit numbers, identify new conifers. 32 Assessment of Generalization. There are three parts to assessment of generalization. 1. Pre-instruction assessment of generalization. It makes no sense to teach students to generalize knowledge to new examples if their knowledge (from instruction during acquisition) is not firm. So, you should review the knowledge you want students to generalize. Review a set of two-digit multiplication problems that students have done before. Correct any errors in the steps (e.g., multiplication or addition facts, lining up the numbers below the line). When they do these problems without errors, then give new examples to which they can generalize the prior---and firm---knowledge. Review words students have been taught to sound out. Correct any errors. When they read the words without errors, then give new examples. 2. During-instruction, or progress-monitoring assessment of generalization. Give new examples (for generalization) in a set—a generalization set. These new examples must be similar to earlier examples that students learned. For example, you taught the sounding out routine with this acquisition set. am ram ma sun run man What new words can you make using the same letters? sam, ran, sum, san (pseudo-word), rum. These are the generalization set. If you use unsimilar new examples, students are likely to be confused or not to see them as basically the same as earlier examples, and they won’t generalize or try their earlier skills. 33 “I can’t read THESE words!” Present these new examples one at a time, and note how well students sound them out. “Boys and girls. Here are some new words. You can sound them out. Don’t let them fool you just because they are new. When I touch under a sound, you say the sound. Don’t stop between sounds.” s u m o---------> Did every student do it correctly? THAT is the progress assessment. Repeat it with each next word in the generalization set. Correct any errors. Note any weak knowledge and firm it up. For example, a few students have forgotten the sound that goes with n; a few other students stopped between sounds. 3. Post-instruction, or outcome assessment of generalization. You have seen this several times now. Simply present the whole generalization set. Correct any errors. Note any weak knowledge and firm it up. Instruction on Generalization The examples in the generalization set must be similar enough to examples in the acquisition set that students know all they need to do the generalization examples. [Please read that sentence again.] If the acquisition set of words does not contain the letter l, then you can’t expect students to sound out new words that have the letter l. 1. Prepare students for generalization by reviewing background knowledge. 2. Tell them they will be applying knowledge to new examples. 3. Assure them that they can do it. 4. Give them reminders. “Don’t stop between the sounds.” “Multiply numbers in the ones column first.” 5. Provide students with a list of steps or a visual guide (e.g., what the solution to a multiplication problem looks like) so that students can guide themselves and check their own work. 34 6. Correct errors. 7. Identify week spots. Firm these at the end of the lesson and before the next lesson. 8. In future lessons, teach new knowledge (for example, new letter-sounds, new figures of speech, new examples of symbolism, new rhyme schemes). Then create a new generalization set (words to sound out, poems to analyze) that enables students to apply the new knowledge. Retention Definition of Retention Retention means that knowledge remains firm (accurate, fluent) despite the passage of time and despite acquiring new and possibly interfering knowledge. What’s the point of education if students forget everything but a few facts? No point. There are three enemies of retention. 1. Students were not firm on the knowledge taught during acquisition. [Maybe the teacher did not do progress monitoring or outcome assessment.] Therefore, there is nothing for students to retain. The solution is simple. Do not go on until students are 100% accurate on new material. 2. Time goes by and students are not using what they learned earlier. So, memory decays. The solution is simple. a. Schedule distributed practice on a sample of things taught earlierto-recently. b. Give students many opportunities to generalize/apply (practice) earlier knowledge. 3. New knowledge interferes with earlier knowledge. This is often because the new knowledge looks similar to the earlier (so students treat it as the same), but isn’t. The solution is simple. Separate instruction on similar looking (but actually different) items. Make sure students are firm on the earlier before you teach the later, similar looking items. 35 Objectives or Aims of Retention The objective is that when you present a retention set (a sample of earlier items worked on), students get most of them right. They are still accurate and fast. Assessment and Instruction on Retention You are teaching many things at once. In elementary school, you are teaching letter-sound correspondence (r says rrr), sounding out words (run ---> “rrruuunn” ---> “run”), spelling, handwriting, addition, subtraction, concepts in science, facts in social studies, and many more. Are you aware of what you are teaching? “Of course! I am teaching new letter-sounds. e, d, f. I have already taught students the sounding out routine with am, ram, ma, sun, run, man. As soon as they know the sounds that go with e, d, and f, I will teach them to sound out new words----seed, feed, seem, fan, and fun. I have already taught students to write all the letters. Now we are working on fluency…” Since you know what you are working on and what you have worked on, it’s no big problem to schedule review and practice to build and assess retention. Every day, before each lesson on a particular subject, review (assess) and have students practice a small sample of what you have already worked on in that subject---cumulative review. For example, students practice translating some Spanish vocabulary words worked on during the week before you teach them new ones during the lesson. This sample is your retention set. In addition, schedule longer sessions for cumulative review---the retention set should draw on material relevant to the new subject, going back a month or so---very early as well as recent items. For example, 1. Before you teach vocabulary found in a new historical document, review/assess earlier vocabulary. 2. Before you teach new letter-sounds, review/assess earlier ones. 36 3. Before you teach new figures of speech (synecdoche, oxymoron), review/assess earlier ones (metaphor, simile, alliteration). http://www.nipissingu.ca/faculty/williams/figofspe.htm 4. Before you teach the phases of meiosis http://www.biology.arizona.edu/CELL_BIO/tutorials/meiosis/page3.html review/assess the phases of mitosis. http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/VL/GG/mitosis.html 5. Before you teach new examples of simple addition, review/assess earlier examples. 6. Before you teach conjugation of re verbs in French, review/assess er verbs. 7. Before you teach long division, review/assess estimation, multiplication, and subtraction. In addition to review and practice, make sure that you separate instruction on items that may be confusing. For example, do not teach metaphor and simile near one another. They differ only by the words “like” or “as.” Do not teach mitosis and meiosis near one another or at the same time. Do not teach the sounds that go with b and d near each other. Instead, make sure students are firm and automatic on the early item before you teach the later. Another way to assist retention is to provide students with written routines or diagrams that they can use to guide and check themselves. For example, the list of steps in analyzing poems. Summary You have learned another tool for designing instruction---phases of mastery. Too often, teachers work only on the first phase---acquisition of new knowledge. The result is that students forget most of it. What a waste! When students are firm on new knowledge learning during the phase of acquisition, you 37 1. Build fluency, by modeling faster performance, adding special tempo cues, practice, and speed drills. 2. Work on generalization, by modeling how to transfer earlier knowledge to new---similar---examples, in a generalization set. 3. Increase retention, with cumulative review and practice (of a retention set of examples) and by frequent opportunities for generalization. Each phase has objectives or aims, and each phase has its own kind of preinstruction assessment; during instruction or progress monitoring assessment (immediate acquisition tests; speed drills and charting rates); and postinstruction or outcome assessment (delayed acquisition tests; retention tests). Use this information to evaluate and to improve your curriculum materials, instructional designs, delivery of instruction, and your students’ skills. We have used the words pre-skills and background knowledge many times. We’ve said that you have to assess and firm up students’ pre-skills before you teach something new that REQUIRES the pre-skills. For example, it makes no sense to teach students tw-digit multiplication if they can’t do (or if you don’t KNOW if they can do) single-digit multiplication. But how do you know what the pre-skills are that you should assess and firm up? Task analysis tells you. Task analysis is our next tool for designing instruction. Useful Readings Binder, C. (1996). Behavioral fluency: Evolution of a new paradigm. The Behavior Analyst, 19, 163-197. Brophy, J.E., & Good, T.L. (1986). Teacher behavior and student achievement. In M.C. Witrock (Ed.), Third handbook of research on teaching (pp. 328375). New York: McMillan. Dougherty, K.M., & Johnston, J.M. (1996). Overlearning, fluency, and automaticity. The Behavior Analyst, 19, 289-292. Haring, N.G., White, O.R., & Liberty, K.A. (1978). An investigation of phases of learning and facilitating instructional events for the severely 38 handicapped. An annual progress report, 1977-78. Bureau of Education of the Handicapped, Project No. 443CH70564. Seattle: University of Washington, College of Education. Horner, R.H., Dunlap, G., & Koegel, R.L. (Eds.) (1988). Generalization and maintenance: Life-style changes in applied settings. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Kame’enui, E.J., & Simmons, D.C. (1990). Designing instructional strategies: The prevention of academic learning problems. Columbus, OH: Merrill. Rosenshine, B. (1986). Synthesis of research on explicit teaching. Educational Leadership, 43, 60-69. 39 Summary of Phases of Mastery Definition Relevant Instructional Objectives or Aims Relevant Instructional Procedures Acquisition of Verbal Associations, Concepts, or Rulerelationships. The student learns a new verbal association, concept, rule-relationship, or cognitive routine from the examples (and perhaps nonexamples) presented and described---the acquisition set. Accuracy. 100% correct. Fluency Generalization Retention Accurate, rapid, smooth (nearly automatic) performance. The accurate application or transfer of knowledge to new examples--called a generalization set. Knowledge remains firm (accurate and fluent) despite the passage of time and despite acquiring new and possibly interfering knowledge. Accuracy plus speed (rate), usually with respect to a benchmark. When presented with a generalization set (new but similar examples) students respond accurately and quickly. Focused instruction: clear and concrete objective; gain attention; frame; model, lead, immediate acquisition test; examples and nonexamples; error correction; delayed acquisition test; Modeling fluent performance 1. Review and firm up knowledge to be generalized. When presented with a retention set (a sample of earlier items worked on), students respond accurately and quickly. 1. Every day, before each lesson on a particular subject, review (assess) a sample of what you have already worked on in that subject. Special cues; e.g., for tempo. Repetition (practice) Speed drills (practice) 2. Use a generalization set (new examples) that are similar to earlier examples that students learned. 2. Separate instruction on items review. Examples and nonexamples are selected from an acquisition set. Work on fluency should at first be with familiar materials—text to read, math problems to solve. Why? 3. Model how to examine new examples to determine of they are the same kind as earlier-taught examples, and therefore can be treated the same way. If you use NEW examples, you are really working on generalization. Therefore, if students do poorly on fluency assessments, you won’t know if they just can’t generalize or whether they were never firm to begin with. Assess pre-skills or background knowledge essential to the new material. Measure rate (correct and errors) before instruction on fluency During-instruction, or progressmonitoring assessment Immediate acquisition test/check after the model (“This letter makes the sound ffff”) and the lead (“Say it with me.”). Frequent (e.g., daily) measure of rate (correct and errors) during instruction on fluency, in relation to a fluency aim or benchmark 3. Provide written routines or diagrams that students can use to guide and check themselves 4. Assure students they can do it. 5. Provide reminders of rules and definitions. 6. Correct errors, and reteach as needed. Review/test knowledge you want students to generalize. Pre-instruction assessment that may be confusing; e.g., simile and metaphor. Add new examples to the growing generalization set. Have students work them. 41 Review/test knowledge you want students to retain. This would probably be the most current delayed acquisition test—after a lesson or unit. Add examples from the most recent lessons and rotate examples from earlier lessons, to form a retention set. Post-instruction, or outcome assessment The immediate acquisition test/check is, for example, “Your turn. (What sound?” “Is this granite?” “Now, you solve the problem.”) Delayed acquisition test using all of the new material. “Read these words. First word. What word?...Next word. What word?” Do this every time to assess retention. Rate (correct and errors) at the end of instruction on fluency, in relation to a fluency aim or benchmark. If students have responded accurately to past generalization sets, the latest one given is the outcome assessment. Or, “Is this an example of tyranny? [Yes] How do you know?... Is this an example of a republic? [No] How do you know?” 42 If students have responded accurately to past retention sets, the latest one given is the outcome assessment. 43