Kingship in Ancient Egypt

advertisement

Kingship in Ancient Egypt

What is a king in Ancient Egypt?

There are several Ancient Egyptian words for king: nswt and ity are perhaps the most

common. The Ancient Egyptian word for kingship is nsyt. In Ancient Egyptian lists of words

('onomastica'), kings are a separate category of beings. The character of kingship doubtless

changed considerably over the three thousand years of Ancient Egyptian history, but there are

some constant features:

from the First Dynasty to the Roman Period (about 3000BC-AD300), the king of

Egypt is called Horus (god of order and celestial power), and has a separate 'Horus

name', identifying him as a unique manifestation of that god

from the Fourth Dynasty to the Roman Period (about 2600BC-AD300), the king of

Egypt is called 'son of Ra' - for most of that period, the phrase 'son of Ra' is a

prominent title placed before the name that the king was given when he was born

the king of Egypt had a special set of names and titles - by the Middle Kingdom (about

2025-1700 BC) there were five: Horus name, name '(of) the Two Goddesses', HorusGold name, title nswt bity (dual king) with another name taken at accession to the

throne (throne name), and son of Ra title with birth name

the throne name and birth name were each written in a special motif, an oval with flat

end-line - this was called Sn 'ring' in Egyptian, and seems to correspond to the

description of king and sun-god as ruling all that the sun-disk encircles in hieroglyphic

inscriptions - early Egyptologists gave the name 'cartouche' to the motif

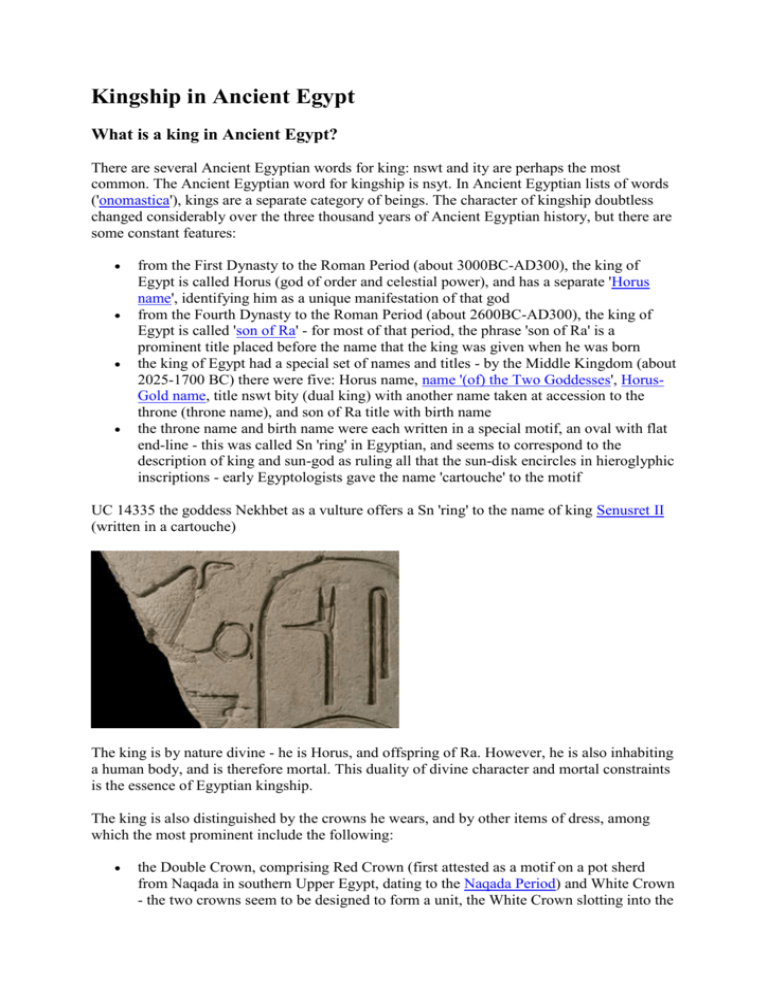

UC 14335 the goddess Nekhbet as a vulture offers a Sn 'ring' to the name of king Senusret II

(written in a cartouche)

The king is by nature divine - he is Horus, and offspring of Ra. However, he is also inhabiting

a human body, and is therefore mortal. This duality of divine character and mortal constraints

is the essence of Egyptian kingship.

The king is also distinguished by the crowns he wears, and by other items of dress, among

which the most prominent include the following:

the Double Crown, comprising Red Crown (first attested as a motif on a pot sherd

from Naqada in southern Upper Egypt, dating to the Naqada Period) and White Crown

- the two crowns seem to be designed to form a unit, the White Crown slotting into the

Red Crown and being held in place by its distinctive frontal coil; the first monument

on which a king is shown wearing both crowns is the siltstone cosmetic palette of king

Narmer (depicted on one side of the palette wearing the White Crown, and on the

other side wearing the Red Crown); some deities wear one or other of these crowns,

but they are not worn by the human subjects of the king

the headcloth of kingship, in Egyptian 'nemes'

an adaptation of a close-fitting cap, the Blue Crown (sometimes called 'War Crown' in

earlier literature, but more research is needed on the precise meaning of all crowns

relative to one another and to their contexts)

the long straight-edged beard, distinct from a shorter beard worn by officials and a

tubular beard with curling rounded end worn by gods

pleated kilt with ornate frontal panel, in Egyptian 'shendyt'

Depictions of the king often show a rearing cobra at the brow (in Egyptian iart 'the rising

goddess', source of the term uraeus often used in Egyptology); the rearing cobra also protects

the sun-god, and appears on the solar disk worn by goddesses. This is another feature

reinforcing the solar character of Ancient Egyptian kingship.

'red crown'

'white

crown'

king's head

with a

king with

nemes 'blue crown'

headdress

The Divine Birth Cycle in Egyptian art

How literally should the title 'son of Ra' be interpreted? In the temple built for queen

Hatshepsut as king at Deir el-Bahri, on the West Bank at Thebes (about 1450 BC), there is a

cycle of figurative scenes narrating the divine birth of the king. The same sequence of scenes

is found for the birth of king Amenhotep III in the temple of Amun at Luxor (about 1375 BC),

and again in temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, where the birth of the god Horus is

the subject. This Cycle of Divine Birth shows the creator-god Amun-Ra taking the form of a

human man to impregnate the woman chosen to give birth to the future king: she is the human

vessel within which the purely divine seed of the creator can grow. Thoth, god of knowledge

and writing, appears to the woman to reveal that she is to give birth to the son of the creator.

In addition to these formal royal depictions, there is an earlier informal version in a literary

narrative cycle preserved in one copy on a papyrus (Papyrus Westcar, now in the Egyptian

Museum, Berlin). The copy dates to the Second Intermediate Period (about 1600 BC); the

composition is in a late form of the Middle Egyptian phase of the language, indicating a date

of composition in the late Middle Kingdom (about 2025-1700 BC) or Second Intermediate

Period (1850-1600 BC). The tale relates the birth of three Fifth Dynasty kings to a woman

named Ruddjedet, wife of a priest of Ra in Lower Egypt, during the reign of the Fourth

Dynasty king Khufu; the birth is assisted by the goddesses Isis, Nephthys and Heqet, with the

god Khnum as their porter.

What are the implications of this narrative?

1. the king is the same substance as the creator - he is not human, but divine

2. there is no such thing as 'royal blood' or a royal family as we might understand it there is only the direct descent from the sun-god

3. human women are not easily 'sons of Ra' - the sun-god is male, and so his offspring is

most naturally also male; nevertheless, there are several cases in Egyptian history

where a woman claimed kingship, most notably Hatshepsut, but also Sobekneferu in

the Twelfth Dynasty (1800BC) and Tausret in the Nineteenth Dynasty (shortly before

1200 BC)

4. although the king is regularly male, all others in close connection with kingship are

female - it is human women who come into direct physical contact with the sun-god to

produce the next king, and with the reigning king as his wife; therefore 'king's mother'

and 'king's wife' are all-important religious positions in court, higher than 'king's

daughter' and 'king's son' - there is no king's father, as that is the sun-god, but, where

the sun-god chooses a woman who is not wife of the reigning king, her husband is

given the title 'god's father when the child becomes king

Questioning the divinity of the king

Although there seems never to have been any expression of opposition to the belief in the

divinity of the king, the mortality of the human body occupied by the king during his reign on

earth provided opportunities for attitudes other than reverence. These find expression

principally in literature: narrative tales may depict a king with qualities at variance with

behavioural norms (Sneferu as lascivious, and Khufu as over-zealous in his quest for

knowledge, both in the Tales from the Court of King Khufu, on Papyrus Westcar), and the

Teaching of King Amenemhat I seems to describe the murder of the king.

In the limited data on political history, event by event, there are indications of strife at court,

and attempted or successful plots against the reigning king:

a group of documents on papyrus indicate that king Ramesses III was the victim of a

conspiracy involving members of court

from ancient Greek historiographical sources for the Twenty-sixth Dynasty it is known

that Ahmose II (Amasis) usurped the throne from Wahibre (Apries)

Such events seem not to have disrupted the structure of kingship and belief in the divinity of

the king: human beings have unlimited capacity for adaptation, and devout believers are able

to destroy what seems, externally, central to the belief system.

What does a king have to do in ancient Egypt?

There is no ancient Egyptian treatise on kingship, but one religious composition, first attested

from the New Kingdom (about 1550-1069 BC), but perhaps composed earlier, includes a

passage explaining the principal functions in Egyptian terms (Assmann 1970):

'Ra has placed the king on the earth of the living for ever and eternity

to judge between men

to make the gods content,

to make what is Right happen,

to annihilate what is Wrong,

to offer divine offerings to the gods

and voice offerings to the blessed dead.'

This ethical and ritual definition of kingship is of exceptional importance, but it is inevitably

partial, notably in concealing beneath the phrase 'to make what is Right happen, to annihilate

what is Wrong' the economic and military aspects of control. These economic and military

aspects are more prominent in other ancient writings about kingship, above all the annals. An

early and unusually detailed example is a fragmentary inscription of Amenemhat II from

Memphis, preserved on at least two reused blocks, one recorded in an excavation by W M F

Petrie, and a much larger segment first recognised in modern times by W K Simpson. The

events at the royal court are documented in chronological sequence, though without

specifying month and year dates. The larger block preserves the following entries (see the

preliminary report by Altenmüller/Moussa 1991):

Summary:

(1) Income

Arrival of foreign delegations: 14-15, 19

Trading and mining expeditions: 8 (and 9?), 16, 21

Military expeditions: (9?), 10, 20

Other activity by the king: 22

(2) Expenditure

Offerings and cult: 1-7, 11-13, 17-18, 24-29

Distribution of income: 23

More detailed breakdown, line by line (the division into entries is not always the same as that

in the interpretation by

Altenmüller/Moussa 1991):

Item 1: establishment of offerings (line 1, mainly lost)

Item 2: establishment of daily cult and festival cult offerings (line 2, mainly lost)

Item 3: 'offering to the dual king Kheperkara in the lake of ...' (lines 2-3? part lost: 'lake' is a

broad term that may refer to an irrigated estate here; Kheperkara is the throne-name of

Senusret I; it is not certain that the items offered from the pr-nswt 'king's domain' are part of

the same entry, or separate)

Item 4: offerings from the wine-production centre on days 25 and 26 of a month in the season

of flood (perhaps the fourth month of that season, as days 25 and 26 are the festival of Sokar,

one of the most important in the ancient Egyptian religious calendar) (line 4)

Item 5: 'giving the house to its lord in the temple ...' ('giving the house to its lord' is the name

of the ceremony for founding a temple; it is possible that this is part of the same series of

entries in the preceding lines, involving the establishment of a cult for Senusret I, perhaps in

the Fayum) (line 4)

Item 6: 'following the acacia-wood statue of Nubkaura' (Nubkaura is the throne-name of

Amenemhat II; the following lines include a reference to 'the chest of giving the house to its

lord, with its full equipment', indicating that this is a continuation of the previous item) (lines

5-6, perhaps including more than one item)

Item 7: 'offering divine offerings when they are set up' (presumably the one-off offerings

made at the installation of the objects cited in item 6) (line 7)

Item 8: 'despatching an expedition to Khenty-she' (Khenty-she means 'the one in front of the

lake', and has the mountain-land determinative used for foreign lands - it has been identified

as Lebanon from the products brought back by the expedition, recorded later in the

inscription) (line 7)

Item 9: recruiting manpower (unclear whether this refers to item 8 or item 10, or another need

for manpower) (line 8)

Item 10: 'despatching an expedition with an overseer of troops to destroy Syrian Iwa [...]' (the

place-name has not been identified with certainty) (line 8)

Item 11: donation of cult equipment from the pr-nswt 'king's domain' to the cult of the god

Mont in Iun(y) (Armant) and Djert(y) (Tod), each receiving a vessel of 'Asiatic copper' (it is

not clear which other items in line 9 go to the Mont cult) (line 9 and lower end of line 10)

Item 12: 'following the goddess [..] to her temple in Wadi Natrun' (probably part of the next

entry) (line 10)

Item 13: 'making a wood statue of the overseer of Wadi Natrun dwellers Ameny permitted (?)

to him in Djefa-Amenemhat' (the place-name Djefa-Amenemhat has the hieroglyphic

determinatives pyramid and town, and is probably therefore a settlement, small or large, near

the pyramid of Amenemhat II at Dahshur) (line 10)

Item 14: arrival of deputation from Kush and Webat-sepet (Nubian Nile Valley and desert

valleys), and record of the produce brought by them (lines 11-12)

Item 15: 'arrival in obeisance of the children of rulers of Syria, bringing with them...'

(followed by list of produce) (lines 12-13)

Item 16: 'return of the expedition despatched to the terrace of turquoise, bringing with them...'

(followed by list of produce, including types of object not found in Sinai, the turquoise

source) (lines 13-14)

Item 17: 'setting up a birth window' and related items in Djefa-Amenemhat (the place-name

Djefa-Amenemhat here has the hieroglyphic determinative pyramid without the town, and is

probably therefore the pyramid or pyramid-complex of Amenemhat II at Dahshur) (line 14)

Item 18: installing architectural elements 'in the temple of the dual king Kheperkara which is

in the Landing-stage of Senusret in the region of the Ways of Horus' (Kheperkara is the throne

name of Senusret I; the ways of Horus are the land routes from the eastern Delta across

northern Sinai to western Asia) (line 15)

Item 19: 'arrival in obeisance of the prospectors of Tjempau, bringing with them...' (followed

by list of produce) (Tjempau has not been identified) (line 15)

Item 20: '[return of the expedition and overseer of] troops despatched to destroy Iwai and to

destroy Iasy; number of living captives brought back from those two hill-lands - 1554'

(followed by list of produce) (Iwai and Iasy have not been identified; Iwai is presumably the

same as the land named Iwa in Syria in item 10 - this would be the return of that expedition)

(lines 16-18)

Item 21: 'return of the expedition despatched to Khentyshe in two boats, bringing with them...'

(followed by list of produce, and specification of the distribution of some part of the total) (for

Khentyshe, see the entry for the despatch of this expedition, Item 8 above) (lines 18-23)

Item 22: 'resting of the king in the southern Fayum, Lake of Kheperkara; weaving by His

Majesty of a net of 12 cubits in span length with his courtiers' (followed by account of a catch

as foretold by the king; for the Lake and Kheperkara, see Item 3 above) (lines 23-25)

Item 23: 'giving favour (consisting of) estate-workers, fields, gold, cloth, all good things in

great quantity, to the overseer of troops Ameny and to the soldiers who returned from

destroying Iwai and Iasy' and to other groups (passage partly destroyed, but apparently all on

distribution, including to the cults of deities) (lines 25-27)

Between lines 27 and 28 is a thicker vertical emerging from the head of a kneeling deity with

arms raised, probably the hieroglyph for year on the head of the personification of eternity.

Line 28 contains the titulary of king Amenemhat II with the epithets 'beloved of Atum lord of

Iunu (Heliopolis)' and 'given life like Ra eternally', followed by the name of the goddess

Seshat 'Writing' and two small figures, one named ir 'action', the name of the other lost

(perhaps, as in later New Kingdom (about 1550-1069 BC) examples, 'action' and hearing')

This is probably the end of one year of entries; the number of the regnal year might have been

written at the top of the column, now lost.

Item 24: broken entry involving the ritual of 'giving the house to its lord' and ritual equipment

(compare Item 5, above) (line 29)

Item 25: 'following Sobek lord of Rewamhu to the temple of Sobek lord of Rewamhu' and

reference to ritual equipment (line 29)

Item 26: broken entry with reference to a province named after a bull (in the Delta?) and

(same entry?) a deity in Ipetsut (Karnak) and Mont (lines 29-30)

Item 27: 'following a [.. and] gold image of Nubkaura to the temple of Amun in Ipetsut' and

reference to ritual equipment (line 30)

Item 28: 'following [...] and Nephthys in the double-sceptre province; giving the house to its

lord [...]' with reference to ritual equipment (line 31)

Item 29: broken entry referring to donation of fields to provide daily and festival offerings for

the god Igay in the double-sceptre province (lines 32-33?)

The last lines at the left of the block are more extensively damaged; the lower edge of line 36

mentions the god Seth in the town Wenes, and, as this cult seems related to the cult of Igay in

the double-sceptre province, the donations to cults in that province may have taken up all of

lines 28 to 36. Of lines 37 to 41, very little remains.

The cult of the reigning King in ancient Egypt

Like the Emperors of early imperial Rome, ancient Egyptian kings received formal worship

during their lifetimes. However, they were mortal: this creates a duality, of divine eternal

kingship and mortal body in human form.

Temples to the cult of the king at the burial place

At the burial place of each king, there is a place for the worship of that king, attested in

architecture at least from the First Dynasty to the New Kingdom (about 3000-1070 BC).

Examples:

First Dynasty,

Second

Dynasty

Old Kingdom

Middle

Kingdom

New Kingdom

pyramid

variations on

cult enclosures

complex for

the theme of temples of kings on

for each king

the cult of each the pyramid

the West Bank at

buried at

king, as at

complex, as at

Thebes

Abydos

Meydum

Lahun

Additional temples to the cult of the king

Other places of worship for the king would have included the palace, and secondary chapels

in the precincts of temples to deities; in some reigns there were also major temples for the

king constructed at several places in addition to the focus of the eternal cult at the burial

place, most strikingly for Amenhotep III and Ramesses II.

Example of a chapel for the cult of the king (Hwt-nswt) in the precinct of the local main deity

(Koptos) and a kingship temple connected with a palace (Gurob):

chapel of

temple for the

Nubkheperra

cult of

Intef at Koptos Thutmose III

The lifespan of a temple to the cult of the king

Such temples would have had lives of varying length: there is evidence that the cult might be

maintained, but the economic resources diminished, a century or two after the death of the

king, as George Reisner found in his excavation of the temples in the pyramid complex of

Menkaura at Gizeh. Each new king would have concentrated the resources of the land on their

own cult, once the predecessor had been buried: therefore the cult probably enjoyed its peak

during the lifetime of the reigning king, and its resources in land, equipment and sculpture

were probably already being diverted in the immediately following reign.

Hymns to the King

An important literary expression of kingship cult is the Hymn to the King (in Egyptian dwA

nswt). Many examples survive from the New Kingdom (about 1550-1069 BC), and there are

depictions of such worship in the form of an official kneeling with arms raised before the

name of the king; an example found at Memphis and dating to the reign of Saamun (Twentyfirst Dynasty) is accompanied by a hieroglyphic inscription giving the phrase dwA nswt.

The ancient Egyptian expression of kingship seems not to distinguish in essence between the

cult of the living and the cult of the dead king: in both stages of existence, this is the divine

king. Therefore the depictions and inscriptions concerning the cult of the king cannot

necessarily be dated directly from their contents. W. M. F. Petrie retrieved from the town site

near Lahun a papyrus bearing hymns to King Senusret III; these are the earliest such hymns

preserved in manuscript form. Their contents do not reveal whether they were to be sung in

the presence, or lifetime, of the king, or in a festival or ritual involving the statues of that king

in the temple for the cult of his father Senusret II at Lahun.

compare: Cult of kings after their death: the success stories