History, Current Policies and Future Challenges

advertisement

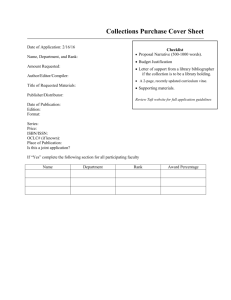

The Australian Classification Board: History, Current Policies and Future Challenges The invitation to speak here tonight came to me in my capacity as the Director of the Classification Board or as it might be better understood in the old parlance of Chief Censor. That certainly was the title in the time of the “lewd and scandalous” books that are the subject of the exhibition that has just opened. So here I am to discuss the history of classification, the current classification system and the challenges the Classification Board faces in a rapidly evolving, technologydriven, increasingly borderless environment. I will punctuate the discussion with some examples and observations on the classification (and previously censorship) of books in Australia. Australia has certainly come a long way since the early days of censorship when (prior to the advent of films) the law was mainly concerned with the importation of books. Under the classification scheme that exists today books – that is novels and literature as we know it – rarely come before the Classification Board. In Australia, the Commonwealth has always had a role in censorship. For most of the 20th century, censorship, occurred under Customs Regulations1 which prevented the 1 The Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations and the Customs (Cinematograph Films) Regulations Page 1 of 24 importation of films or publications if they offended against the criteria set out in those regulations. Books could be seized by Customs for being blasphemous, indecent or obscene. Some famous titles that have been prohibited imports in the past included Ulysees, Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the subject of a recent episode of the ABC’s First Tuesday Book Club – Portnoy’s Complaint. Until reforms in the 1970s and 80s the basis of most Australian censorship law rested on concepts of obscenity and indecency. The English definition of obscenity, known as the Hicklin test, was incorporated with variations, into Australian law. It was articulated in 1868 by Chief Justice Cockburn who said: “. . .I think the test of obscenity is this, whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscene is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”2 Since the 1970s there have been profound changes in the approach to censorship in Australia including the adoption of the concept of classifying material on the basis of the views of 2 R v Hicklin (1868) LR 3 QB 360 at p 371 Page 2 of 24 reasonable adults and changing the names of the Censorship Board and the Censorship Review Board to reflect that: “… rather than focussing on preventing material from being disseminated, policy now concentrates more on classifying films and publications into defined categories, with restrictions on dissemination only being imposed at the upper limits of what is considered acceptable by the general community.”3 As a result of the significant evolution of censorship in the latter part of the 20th century, we now have a classification scheme that classifies material into appropriate categories rather than looking for reasons why it should be banned. The primary purpose of the scheme is to provide information to consumers, particularly parents, so that they may make informed decisions about what they or their children see, read and play. Australia has a fully cooperative National Classification Scheme which was established under legislation introduced in 1995. Under this model the Commonwealth is generally responsible for classification while the States and Territories are responsible for enforcing breaches of classification requirements. Each State and Territory makes their own laws about what material is permissible in their jurisdiction – while there is 3 Australian Law Reform Commission Report #51 on Censorship Procedure (1991) Page 3 of 24 significant uniformity – there are some distinct differences. Eg. Material classified X18+ may be legally sold, hired and distributed in the ACT and the Northern Territory but not in any of the States. The Board is a statutory body, independent from the Government and also separate and independent from the Classification Review Board. The Board makes classification decisions by applying provisions in the Classification Act, the National Classification Code and the relevant classification guidelines. These legislative instruments require unanimous agreement by Commonwealth, State and Territory Ministers with responsibility for censorship matters. The Board currently has seven full time members – three men and four women - ranging in age from their mid twenties to 70 years old - who represent a variety of academic qualifications, professional backgrounds and life experience (including people who are parents and grandparents). As required by legislation, membership of the Board is broadly representative of the community. Each Board member is generally appointed for a fixed term of three years. Members have a statutory limit of seven years service after which time they cannot be reappointed. In Page 4 of 24 actual fact, the Board turns over much more frequently than that. This is important for ensuring that the Board makes decisions which are consistent with community standards - regular turnover of Board members injects not only “new blood” but is a mechanism for keeping pace with changes in attitudes and community standards over time. Along with the other members of the Classification Board, it is my job to apply the legislation to decide on classifications for films, computer games and certain publications. The primary purpose of the scheme is to provide information and advice to the public so that they can make informed choices about entertainment material for themselves and those in their care. In fact, the Board does not “censor” material at all and must classify it in the form it is submitted. Unlike schemes in other countries, the Board does not edit material or recommend modifications to publishers or filmmakers – we only determine a classification and consumer advice. The classification scheme is fundamentally based on the principle that adults should be free to choose what they read, hear and see – with some limited exceptions. Exceptions include child pornography, gratuitous or exploitative depictions of sexual violence, cruelty and detailed Page 5 of 24 instructions in crime or violence. This type of content is Refused Classification and not able to be sold or distributed in Australia. As mentioned earlier, another important principle underpinning today’s classification decision-making is the concept of community standards. The ‘community standards’ test refers to ‘the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults’. A ‘reasonable adult’ is considered to possess common sense and an open mind, and an ability to balance personal opinion with generally accepted community standards. The ‘reasonable adult’ test is used in two different senses - as a measure of community standards and also as an acknowledgment that adults have different personal tastes. Of course community standards are not a clear cut concept and they are often in a state of flux. Views vary widely within any community, so there will always be differences of opinion about where the balance should lie when applying a community standards test and the principle that adults should be able to read, hear and see what they wish. There will always be certain material such as child pornography which the community will not tolerate for obvious reasons. Page 6 of 24 However, for other material – particularly at the high-end of the spectrum where decisions may result in material being restricted or banned entirely - the views of individuals within a community can be distinctly at odds with one another. The most controversial classification decisions today typically illustrate this point…..I’m sure many of you will have followed the commentary on the recent decision for the film, Salo. Both ends of the spectrum – the supporters and the detractors – are equally vocal, passionate and convinced that they hold the ‘right’ view and also that they speak for the majority of the community! Similar controversy has surrounded classification decisions for several books in the past few years….but first let me explain a little about the classification of publications today. Page 7 of 24 Publications Under the current system only publications which are deemed to be ‘submittable’ must be classified by the Classification Board. In accordance with the Classification Act, ‘submittable’ publications are defined as those which are: - likely be Refused Classification (ie. banned), - likely to be offensive to the extent that they should not be sold or displayed as an unrestricted publication, or - unsuitable for a minor to see or read. It is generally the responsibility of the publisher or distributor to determine whether their publication fits the definition of a ‘submittable publication’ and should therefore be submitted for classification. I do on occasion use my legislative powers to call in unclassified publications that are believed to be submittable which come to my attention (generally through complaints from the public). The Classification Board classifies a range of submittable publications each year – the significant majority are adult magazines – but also include naturist publications and even the occasional board game. Page 8 of 24 As mentioned earlier, unlike the censorship regime of the early 1900s, books and novels are no longer a focus of the Boards’ activities. That said, the Board will classify books for which a valid application for classification has been made. It is in this context that the Board has classified a range of books including the Bible (1993), Art publications and books that discuss issues such as euthanasia and terrorism. It is in the realm of publications that perhaps the greatest visible shift in censorship has occurred. Consider that many of the books that were previously not allowed into Australia were considered offensive for their descriptions and discussions of sexual activity or other apparently depraved and permissive behaviour. Today we have an entire genre legally available of such material that is not simply text-based but represented in full colour pictures and images of real people! It could be argued that controversy generated today by Board decisions on publications, is sparked by the fact that the item in question is, in fact, a book. I would now like to share with you the background to some of the interesting decisions involving books that have prompted significant debate in the broader community, the media, members of Parliament and indeed posed challenges for the Page 9 of 24 Board during my time as Director and also under my predecessor. Islamic texts In late 2005 eight ‘Islamic texts’ were submitted for classification as law enforcement applications. The Board classified them as Unrestricted. The Unrestricted category for publications encompasses a wide range of material, but is not likely to include material that offends a reasonable adult to the extent that it should be restricted. In July 2006, the Board’s decisions were subject to review by the Classification Review Board, at the request of the Commonwealth Attorney-General at the time. The Review Board confirmed the Unrestricted classifications for six of the eight texts, but decided that two of the texts, Join the Caravan and Defence of the Muslim Lands should be Refused Classification. In accordance with the National Classification Code, the Review Board was of the opinion that the books ‘promote, incite or instruct in matters of crime or violence,’ specifically the crime of committing a terrorist act. In the latter half of 2007, amendments were made to the Classification Act to require that publications, films or Page 10 of 24 computer games that advocate the doing of a terrorist act must be Refused Classification. It became clear in 2007 when these amendments were being debated in Parliament that they were being made, at least in part, to deal with the type of material that was the subject of decisions made by the Board and Review Board in the previous year. The legislative provisions cover material that ‘directly praises the doing of a terrorist act in circumstances where there is a risk that such praise might have the effect of leading a person … to engage in a terrorist act.’ It is not designed to capture depictions or descriptions of terrorist acts ‘done merely as part of public discussion or debate or as entertainment or satire.’ Since these amendments came into effect, the Board has only Refused Classification to one item on the basis of this legislative provision. Online content was referred to the Board for classification in July 2009 by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (the ACMA). The film, Islamic Army in Iraq, consisted of a webpage which opened with a prayer of praise to Allah followed by a list of American losses incurred during the war. It was Refused Classification on the basis that it advocates the Page 11 of 24 doing of a terrorist act and in this particular instance ‘…directly praises the doing of a terrorist act…’ Matters relating to online content and websites are the responsibility of the ACMA. I will touch on this point later in this presentation. The Peaceful Pill Handbook Also in late 2006, the Classification Board classified The Peaceful Pill Handbook by euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke, Category 1 restricted. This classification means the book is restricted to adults. In early 2007, the Classification Review Board received two applications to review this decision, one from the interest group The Right to Life Association, and the other from the Attorney-General at the time. The Review Board decided to set aside the decision made by the Board and Refused Classification to the book, as in their view, it instructed in matters of crime relating to the manufacture, storage, use, possession and importation of barbiturates, which are generally a prohibited drug. The Review Board decision means that the Peaceful Pill Handbook cannot be sold in Australia, nor can it be legally downloaded online. Page 12 of 24 In 2008, another of Mr Nitschke’s books, Killing Me Softly, came to my attention through various media reports. I decided to use my legislative powers to call in this book for classification. The Classification Board subsequently classified this book Unrestricted. In the view of the Board, the book dealt with adult themes with a high degree of intensity in a discreet way, that was low in impact and not exploitative, and did not instruct or incite the committing of a crime. Page 13 of 24 In relation to these examples there is a fine line between content which discusses themes, issues and legitimate debate about euthanasia, and content which instructs and encourages criminal acts that facilitate euthanasia, such as the manufacture of drugs or removal of evidence of suicide to prevent the reporting of such a death to a Coroner. A major challenge for the Board when dealing with contentious material, is determining at what point material goes beyond discussing an illegal act to clearly instructing or inciting an illegal act. A key feature of the publications discussed above is that they all discuss highly controversial and sometimes criminal acts. These are vexed issues that elicit emotive responses and raise serious questions that are debated by policy-makers and regulators not just here in Australia but also abroad. That these publications came before the Board at all demonstrates that community standards are often in a state of flux and can appear to change quite dramatically, for example, in response to global events. Widespread community concerns about ensuring safety from terrorist attacks is a relatively new priority in Australia – driven by events such as the 9/11 and Bali terrorist attacks. Lewd and scandalous – no – but offensive by today’s community standards and concerns – yes possibly. Page 14 of 24 By contrast, in 2009, following an application form the ACMA, the Board classified an electronic (ie. online) version of the Marquis de Sade’s novella, Justine, Unrestricted. The novella, published in 1788 and in print since that date, was deemed to be a bona fide artwork. The Guidelines for the Classification of Publications state that ‘Bona fide artworks are not generally required to be submitted for classification as they are not generally considered to be submittable publications’. Art Monthly Another publication which attracted significant attention in recent years was the infamous July 2008 issue of Art Monthly, with a cover photograph by Australian photographer Polixeni Papapetrou of her daughter, entitled ‘Olympia as Lewis Carroll’s Beatrice Hatch before White Cliffs’. The photograph depicted the child sitting nude, in three quarter view, in a painted landscape. This issue of Art Monthly was published very soon after the Bill Henson exhibition at a Sydney Gallery attracted media and community attention. I used my powers to call in the publication for classification. Page 15 of 24 The Board subsequently classified the publication Unrestricted with the consumer advice ‘M - Not recommended for readers under 15 years’. The Board was of the view that the publication was a bona fide arts publication addressing serious issues of interest to the arts community. A minority of the Board was of the view that the images in the publication depicted a child under 18 in such a manner that it was likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult and should therefore be Refused Classification. As a result of community pressure and political decisions in the wake of the Bill Henson and Art Monthly matters, the Australia Council for the Arts’ developed protocols for working with children in art, that came into effect on 1 January 2009. The protocols require Australia Council funded artists and organisations to apply, in certain circumstances, for classification of images of naked real children. The Board has only received one application submitted in accordance with these protocols - the images were classified Unrestricted. In this particular instance, there were two equally interesting and important debates: - whether the images constituted art or (in the extreme view) inappropriate sexualised images of children; and - whether, as art, it should even be subject to classification. Page 16 of 24 Art may fall within the definition of a publication and the Board must classify images if an application for classification is submitted. However the Classification Guidelines allow for bona fide artworks to be classified Unrestricted if they are set in a historical or cultural context, even though the work may offend some sections of the adult community. In the past decade concerns related to the sexualisation of children in the media and protecting children from sexual predators have risen. A change in community standards is evident in the profile and number of interest lobby groups and their success in focussing attention on the issues and for instigating legislative changes. That the Bill Henson images, which have been exhibited in the past, caused such a furore resulting in several applications for classification in the ensuing period, is another example of the shift in community standards in response to technological and social changes that have increased concerns about children’s safety. Another element of the classification scheme is to protect children (including child actors/models) by ensuring that offensive material that contains descriptions and depictions of persons who are, or look like they are under 18, is refused classification. Page 17 of 24 The Classification Code was amended several years ago to bring the age definition of a minor into line with ILO 182 - the international treaty aimed at the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour including child pornography. Under this treaty a “child” is defined as a person under the age of 18 years compared with the age of consent which is 16 years old. The Board has an important role – that it treats very seriously – in relation to classifying material submitted by law enforcement authorities, including items used in prosecutions for child pornography offences. The Board’s experience in dealing with genuine examples of child pornography gives them a very useful perspective that can be applied to the classification of other material. Board members are able to apply their knowledge of child pornography to distinguish between it and, for example, high impact material in dramatic films or artistic representations in publications such as Art Monthly. Adult Publications So is there anything that might be considered ‘lewd and scandalous’ in contemporary Australia? I’ve no doubt that there are people who would point to the proliferation of adult magazines – despite their regulation –as lewd and scandalous. However, complaints are limited and more likely to target Page 18 of 24 concerns around potential depictions of minors rather than the availability or the content of the magazines in and of themselves. On this matter, over the past 18 months a prominent issue raised in public complaints, has been the content and availability of unclassified ‘teen title’ adult publications sold in unrestricted premises such as petrol stations and convenience stores. With titles such as Purely 18 and Finally Legal, it is safe to assume and I can indeed confirm, that such publications contain images of young persons who are depicted to be on the borderline of 18 years old. Classification guidelines in Australia expressly state that exploitative or offensive depictions or descriptions involving someone who is or appears to be under the age of 18 years, must be Refused Classification. Investigations into the matter revealed that the publications being sold had either not been classified by the Board or were different to the versions that the Board had classified. The Board found in many, but not all instances, that the content in these publications contained offensive depictions Page 19 of 24 and descriptions of persons who were or appeared to be under 18 years. In other instances, the Board found that the content was higher in impact than that allowed to be sold in unrestricted premises, and therefore be should be sold in restricted, adult only premises. Interestingly and perhaps the most ‘scandalous’ accusation recently directed at the Board - likely to have been prompted by the Boards attention to the breaches I have just discussed above - is that we display a bias against small breasted women…and on this basis… are banning material! Criticisms have been levelled at the Board regarding the factors it considers when determining the age of persons depicted in publications, particularly the accusation that small breasted women are determined by the Board to appear to be children. This is categorically untrue. The Board members take their responsibilities seriously and consider the overall appearance of persons and the context in which they are depicted, including text, props and poses when making classification decisions. Page 20 of 24 Depicting small-breasted women is not grounds for a publication to be Refused Classification, nor do the classification guidelines refer to the size of a woman's breasts! Classification of online content Generation Y and the ones to follow, who embrace technology and enjoy immediate access to endless streams of information from all over the globe, are now arguably redefining the boundaries of lewd and scandalous. I would posit to you that lewd and scandalous may cease to be so in the age of you-tube videos that instantaneously transmit all manner of behaviour and facebook pages where individuals actively put themselves (all of themselves) on display to the world, as it were. By comparison the content of books that was once so lewd and scandalous is today more likely to elicit a disdainful “is that it?” or dissected and appreciated for its humour value! The online environment is potentially where the greatest challenges lie for governments (here and elsewhere) and for communities in determining standards and boundaries about what is acceptable, permissible and indeed legal. Page 21 of 24 Debates about limits on nudity, privacy issues, racism and bullying online (particularly in relation to social networking sites) are now emerging and gaining momentum. It is these forums that will act as a mechanism for defining community standards into the future. Currently the Board’s role is to classify online content on application from the ACMA. As mentioned earlier, online content is regulated by the ACMA. The Board classifies online content in the same manner as it would classify films, computer games or publications. The content submitted to the Board by the ACMA is vast and varied and the context in which the material is submitted is vital for the Board in determining the correct classification. Once a classification decision is made, this is communicated to the ACMA and it is their responsibility to determine what action is taken from there. The proposals for an internet filter and other matters of policy are for the Government to decide. The Board only applies the law as it is made so it is not appropriate for me to comment on policy issues. What role the Board plays in the future in relation to online content remains to be seen. Page 22 of 24 What is certain is that balancing individual freedoms with practical and enforceable laws that provide an appropriate level of protection online will be difficult and complex. Keeping pace with a rapidly evolving and all encompassing online environment together with highly convergent technologies will also be very challenging. Page 23 of 24 Conclusion The challenge for the Board is to continue to appreciate and understand the evolving nature of community standards and to apply these appropriately when making decisions. Robust community debates, including academic forums such as this conference, are important for gauging what is and what isn’t considered acceptable. The Board monitors this type of exchange of opinions and discourse closely and also welcomes the opportunity to participate. Statistically, from over 7,000 decisions the Board makes each year, publications only make up about 200 decisions. The examples I have discussed today are just a snapshot of the vast and varied work the Board does across a variety of media formats. I hope the matters that the Board has dealt with in recent times have been of interest to you all and that this presentation has provided you with some insights into how the Board operates today including the limits and challenges it faces. Once again, thank you very much for inviting me to take part today. Page 24 of 24