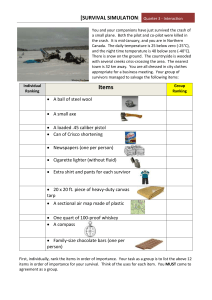

Child Survival Manual - Partners for Development

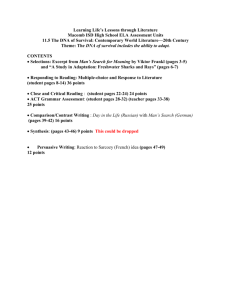

advertisement