Almost everyone agrees that the current East Coast Main Line

advertisement

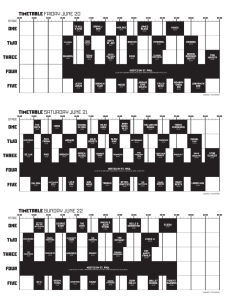

The East Coast timetable : regulatory failure and the case for integration Jonathan Tyler Almost everyone agrees that the East Coast Main Line [ECML] timetable needs recasting. It has evolved incrementally. Such patterns as there are disappear in a cloud of variations. Trains are badly spaced and connections are erratic. Line capacity is poorly used. Two strategies for change are available. Our railway could, collectively, determine that it needs to offer good connectivity across the network and a sense of integration and convenience – in sum, the public service through which progressive countries in Europe have built high patronage and solid popular esteem for their railways. The aim would be to challenge the car culture and to carry a higher proportion of travellers as environmental constraints bite (as distinct from stimulating new trips). With that vision the ECML timetable could only be recast from first principles unencumbered by history and preconditions, but the benefits would be substantial. However, that is not how Britain's railway now works. The model is competition in a free market, despite evidence of its limitations in the particular technology of a railway system. Provision of the infrastructure is separated from the supply of train services, which is itself open to multiple operators with private agendas. Because the monopolistic track provider must be regulated and because the operators make contracts with it the whole is wrapped in a complex legal framework. Yet few people are aware of the alternatives at stake because processes are arcane and often misleadingly focussed on stories about plucky entrepreneurs challenging the big players. This article aims to shift the perspective. The planning process has two elements: the Route Utilisation Strategy [RUS] prepared by Network Rail [NR] and applications for Track Access Contracts. The ECML RUS was "established" in April 2008. The Strategic Rail Authority had identified nearly all the issues in 2005. Little happened during the long gestation of the RUS. It then turned out to be repetitious in analysis and short on committed plans. It eschewed timetabling. Theoretical calculations did not acknowledge the fundamental truth that the real capacity of a multi-purpose railway is a function of the ordering of its train-paths, which itself must be a considered function of the underlying demands. The RUS used no matrix of flows and produced no fresh insights on service priorities (a caution against allocating scarce capacity to short trains was removed between the draft and the final text). Why the RUS followed this course has not been explained, but NR was probably all too aware that it should not pre-empt the applications for access contracts from four sources. The holder of the franchise for the core passenger services, presently National Express East Coast [NXEC], must apply for rights to operate the timetable agreed with the Department for Transport [DfT]. Open Access [OA] companies can apply, and judging by the insubstantial status of Platinum Trains they can do so before they have fulfilled the statutory requirements for a train operator. Freight operating companies [FOCs] are entitled to seek rights for paths they might need in future. And all the other Train Operating Companies [TOCs] running services on or associated with the ECML have existing rights. That would be a difficult mix even for a railway with a Supreme Controller. Instead we have the Office of Rail Regulation [ORR]. Its ideology is competition. It presupposes that each applicant knows its market. It has no timetable vision of its own and relies for technical advice on NR, which understands trains but not passengers. And its procedures only judge the relative merits of applications, although the fact that consultants generate widely differing answers ought to cast doubt on their validity. ORR does have statutory duties to protect the wider interests of users and to facilitate journeys involving more than one operator, but it does not interpret these as an obligation to ask whether mere aggregation of proposals will deliver the optimal result overall. It has certainly not queried the focussing of branding, marketing and ticket discounts almost exclusively on each TOC’s ‘own' internal flows and the corresponding collapse of any real concept of a network. And neither ORR nor DfT seems concerned that strategic timetabling has no champion. In February ORR invited interested parties to state their aspirations (it was reassuring that Merseytravel expressed no intention of running trains on the ECML). ORR did not issue instructions to NR until July to examine the welter of applications. And following the three lost years of the RUS, NR was to report in 11 weeks. To be fair, NR faced an impossible task. This article criticises the system, not the hapless timetablers charged with implementing it. About the only point of agreement was that a new timetable should be based on a repeating pattern. There are six huge problems. In combination the characteristics of the paths being sought self-evidently surpass what can sensibly be planned in a robust timetable. NXEC has franchise commitments that, if unmet, could jeopardise its agreement with DfT. It has already negotiated changes and must safeguard its revenue. (That a franchise of such importance can have been let on a draft timetable that had profound weaknesses is another strange – and expensive – aspect of the system.) Nevertheless, some items spell trouble for any rational plan. In particular, the promise to serve Lincoln 2-hourly rests not on a sound business case but on opening up a regular path for latent Class 6 freights. Hull Trains and Grand Central have disparate operating plans, stopping patterns influenced more by abstruse regulatory conditions than by logic (eg. HT stops at Retford and Grantham but not at Newark and Peterborough) – and ambitions to provide through services for all manner of places. Of course everybody prefers a through train, but it is not physically possible. On the franchised railway new interchanges are being introduced in the name of 'better' timetables. It is peculiar that ORR mechanically processes the OA applications instead of objectively appraising the balance between well-organised frequent connections and occasional through trains. The availability of rolling stock is unclear, since the operators are haggling over the limited fleet of Class 180 units. The Freight RUS forecast growth in traffic. This has been consolidated with a legal status. No matter that previous forecasts have failed to materialise. No matter that a single scenario of endlessly-expanding consumption was quite at variance with the auguries and with the railway's claims to be an agent of environmental sustainability. And no matter that the FOCs are asserting their rights at just the moment when the assumptions have crashed: is it sensible to distort the ECML passenger timetable to accommodate a fourfold increase in container traffic ? All paths other than those of NXEC and existing OA and freight services were to be assumed fixed, except for a (contended) degree of flexing. This imposition arose partly because NR has 2 no authority or inclination to engage in comprehensive recasts, however desirable, but chiefly because the rigid legal structure renders them infeasible. As it happens, other services are also being changed, but in discrete, uncoordinated projects. Piecemeal adjustment engenders poor timetables, and it compares unfavourably with long-term planning in Europe (to 2030 in Switzerland) and successful 'big bang' changes. Network Rail produced its findings on 26 September. Tellingly, the document is entitled 'Capacity Assessment Report'. In other words it does not purport to be a coherent timetable. Rather, it is a commentary on how a bundle of aspirations could be shoehorned onto the line. The Report comprises a description of the proposed paths (but no tabulation of a standard hour), an analysis of performance and an evaluation of whether paths on routes over which operators wish to run through trains can be made compatible with ECML paths (its detail is incommensurate with the size of these markets). In my judgment the Report is bizarre and discreditable. NR has not applied the rules that structure timetables in mainland Europe in order to ensure that every A is linked with every B at an appropriate speed and frequency and through interchanges that are brisk when they are unavoidable. The 'clean sheet' timetable contains buckets of pathing time: eg. an average of 5 minutes in the principal NXEC services, the southbound York 'all stations' standing at Newark for 7 minutes to be passed and a Harrogate service waiting 10 minutes to cross at Poppleton. In any decent modern timetable calling points should be the same and end-to-end times similar for the two directions, but here times vary by as much as 18 minutes, while the Lincoln only calls at Stevenage northbound. NR has no stated policy objective. It passively accepts disruptive constraints. Stops are nonchalantly inserted or taken out without regard to the consequences for markets or connectivity, and provided a station gets a 'quantum' (a revealing term) it is of little concern if they are bunched together (eg. four trains in 31 minutes, then a 29-minute gap) or if valued choices for time-sensitive travellers are negated when a faster train catches up the previous slower one. This approach reaches its nadir with the Scottish services. Attempts to weave the Glasgow extensions of fast Edinburgh paths into the ScotRail plan end in a proposal that the up trains (only) should omit Motherwell, a principal reason for their routeing, and Haymarket, which no one familiar with the geography of Edinburgh could contemplate. The Aberdeen and Inverness trains would run as extensions of the slower Newcastle, which decelerates them. Then, the ECML path having been determined independently, the search for paths in Scotland results in prolonged dwells at Waverley, an admission that the 10:30 from London cannot run to Aberdeen, and timing of the southbound 'Highland Chieftain' so early from Inverness (at 06:22) as to destroy its raison d'etre – and it cannot stop at Gleneagles because a Dunblane local is in the way ! Exacerbating the problems is the presumption that a Class 4 freight should be incorporated every hour between Doncaster and Peterborough and a Class 6 in alternate hours, despite there being at present only seven daytime freights in both directions together and no specification of when the additional paths would be taken up. Moreover these paths depend on precision operating which, if not achieved, will regularly disrupt the passenger service. Other services are only considered where they cause conflicts. The fact that some connections will markedly worsen is not mentioned: for example, the train from Scarborough arrives in York at xx.37, but NR plans the main London departures at xx.09 and xx.30. 3 The proposals are not a standard hour of any distinction, and they only apply for a short interpeak period, since reorganising the peak sits in the 'too difficult' box. NR admits that large tracts of planning have been ignored and that this is a single 'solution' (there having been no time to explore others). Having cobbled together a scheme that shows what can – after a fashion – be fitted in, NR subjects it to a performance analysis that is as detailed as analysis of the quality of the offer is inadequate. One can understand NR's dilemma since performance has become such a fetish, yet one does get a sense of an organisation thinking negatively to protect its own interests. And two important questions are not asked: whether a point comes at which performance is good enough, because customers would prefer a higher frequency and sufficient seats to marginal advances in reliability; and whether regularity itself will promote more disciplined operation (experienced managers believe it will). When ORR initiated a consultation stakeholders weighed in. DfT and NXEC were diplomatic, with curate's-egg comments and a somewhat optimistic belief that, given further work, a passable timetable might be designed. Other TOCs complained about threats to their businesses. Transport Scotland, quite rightly, protested that the plan for their trains is unacceptable. Only London TravelWatch stressed the case for a comprehensive approach. Faced with an impasse ORR has postponed a decision on the allocation of paths from October to January and has asked NR to review the issues. In 11 pages of pettifogging instructions there is no realisation that the exercise is fundamentally flawed. Meanwhile the companies are fighting a battle of partial press-releases. My own researches, supported by players in the industry, have demonstrated that an integrated timetable could yield five times the revenue growth predicted for the NR version, an advantage of over £15 million/year. The plan is believed to be operationally feasible, it optimises the pattern of services for the whole day, it incorporates OA activity, and it best serves the environment by diverting freight to the alternative route via Lincoln. Yet the rules are such that these proposals cannot be studied as an option (ORR, barely understanding the concepts, passed the buck to NR, which has no incentive to respond). For the premier main line (ECML carries more passenger-kilometres than the West Coast) this saga marks a pathetic end to years of planning. Perhaps it was inevitable that the defects in the 'regulated market' model of how to run a railway should come to a head on a route with inadequate infrastructure and rising demand. What happens next is open, but one might hope that at last questions will be asked. Will anyone have the courage to recognise that a railway works best and uses its capacity most effectively when its timetable is planned by a central authority with priorities specified in the broad public interest ? As the London Buses exemplar shows, that can yield excellent results – and of course services are delivered by private operators under contract. It may be too late to achieve a good outcome for the ECML for 2009, but it could still be done for 2010 – as the first stage of a National Timetable Plan that could capture people's imaginations about their railway's future. Jonathan Tyler is an independent consultant [www.passengertransportnetworks.co.uk] 12 Nov 08 4