1

TOWARD A CRITICAL FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING MNE OPERATIONS:

REVISITING COCA-COLA’S EXIT FROM INDIA

Abstract

The exit of Coca- Cola from India in the 1970s has been extensively used in IB textbooks as illustrating

the challenges faced by MNEs in difficult political/regulatory environments. In this paper, we use critical

hermeneutics to challenge the conventional understanding and interpretation of the event. Instead, an

understanding of the macro-economic and historical context suggests that the company had other options

available to it and may have lost a valuable opportunity due to inflexible policies. IB textbooks should be

wary of falling prey to naïve managerialism and instead provide a critical understanding of the operations

within a larger context to their readers.

2

TOWARD A CRITICAL FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING MNE OPERATIONS:

REVISITING COCA-COLA’S EXIT FROM INDIA

This article seeks to develop a critical framework for understanding multinational enterprises

(MNEs) and national governments that overcomes the naïve managerialism of widely used international

business (IB) textbooks produced in the West. Toward that end, we specifically focus upon the

frequently-cited incident of Coca-Cola Company’s exit from the Indian market in the 1970s. This case has

repeatedly been held up in the mainstream Western IB literature as a manifestation of poorly conceived

protectionist policies in India. Our paper, however, strongly challenges such an interpretation of the CocaCola case. In so doing, the present paper’s analysis leads to a significant revision of existing IB

knowledge about Coca-Cola’s exit from India, while simultaneously underscoring the importance of

adopting a critical perspective for understanding not only MNE operations, but also Western IB

textbooks, generally speaking.

International business (IB) and other management textbooks are not only repositories of the

sedimented knowledge of the field, they also play an important role in preparing future managers.

Interestingly, however, during recent years a number of scholars have questioned the perspective being

presented in management textbooks in general (Cummings & Bridgman, 2011; McLaren, Durepos &

Mills, 2009), as well as in IB textbooks more specifically (Coronado, 2012; Fougère & Moulettes , 2011;

Tipton, 2008). For instance, Cummings and Bridgman (2011) have critiqued management textbooks’

general neglect of the history of management knowledge, and suggested that greater historical awareness

among management students would likely encourage them to be more creative managers in the future.

Similarly, on the basis of their critical analysis of a large number of North American management

textbooks published since 1940, McLaren et al. have offered important insights about the role of sociopolitical context in “the social construction and dissemination of management knowledge” (2009: 388).

3

Within the IB field, on the other hand, Coronado (2012) has critically interrogated popular

Western textbooks’ problematic representations of Latin American national cultures, and the role of such

representations in constructing, what she calls, the ‘neocolonial’ manager. Along similar lines, Fougère

and Moulettes (2011) offer a postcolonial critique of discussions of culture in mainstream IB textbooks in

the West. Their study suggests, among other things, that notwithstanding the IB textbook’s repeated calls

for cultural sensitivity, the treatment of other cultures in those textbooks is generally characterized by

cultural insensitivity rather than sensitivity. In a similar vein, Tipton’s study of IB textbooks has identified

a range of “serious weaknesses”—including “errors of fact ... errors of interpretation, and ... problems

with definitions and application of theories of cultural difference”—in those textbooks’ discussion of

culture (2008: 7). Broadly paralleling the endeavors of past scholarly critiques of management and IB

textbooks, one of our objectives in this paper is to understand how certain simplistic and misinformed

interpretations of Coke’s exit from India continue to persist in mainstream IB textbooks. Among other

things, therefore, this article seeks to alert scholars to the importance of developing a self-reflexive and

critical orientation toward the ‘knowledge’ being disseminated by major IB textbooks.

The conceptual approach adopted in this study is situated in the twin scholarly traditions of

political economy and postcolonial theory. While on the one hand, political economy has provided us

with a useful perspective in this paper for critically analyzing the actions of Coca-Cola Company in the

context of economic, political and regulatory developments in India, on the other hand, postcolonial

theory has proved to be of value for examining certain issues of cultural representation relevant to the

present case. It may be useful to note here that the scholarly traditions of political economy and

postcolonial theory seem to exist in a unique relationship which, while often being somewhat tense, is

also highly productive in intellectual terms (Lazarus, 2004; Prasad, 2003, 2012; Spivak, 1999). Not

surprisingly, therefore, researchers from a variety of fields have made increasing calls for creatively

combining the insights of these two traditions for purposes of in-depth critical inquiry (see, e.g., Chari &

Verdery, 2009; Loomba, Kaul, Bunzl, Burton & Esty, 2005). Indeed, an important example of such a call

4

is to be found within the pages of this very journal itself. Specifically, writing their introduction to the

special issue on ‘Postcolonialism’ brought out by Organization in 2011, the special issue editors

explicitly called for ‘deepening and broadening’ postcolonial inquiry in organization studies by means of,

among other things, developing “critique via political economy” (Jack, Westwood, Srinivas & Sardar,

2011: 281). Accordingly, the present paper may be seen as an instance of critical organizational research

informed by a postcolonial sensibility that draws significantly upon the insights of political economy. For

purposes of data analysis, this paper utilizes the methodology of critical hermeneutics. The usefulness of

critical hermeneutics for this research has been discussed later in the methodological section of the paper.

We focus upon Coca-Cola in this article for a number of reasons. As all of us are well aware,

descriptions of corporate actions are quite commonly used to illustrate concepts in textbooks, and

publishers frequently advertise that their books are ‘packed with examples.’ These examples seek to show

how theory works in the ‘real world.’ Examples are drawn, most often, from the experience of MNEs for

two reasons. First, the field of IB has generally focused on the activities of MNEs as they have led

internationalization of business and thereby provided the environment for scholars to study. Second, there

is publicly available information about the activities of MNEs and textbook authors can find examples

more easily to draw upon.

Coca-Cola is an MNE that is frequently referred to in IB textbooks owing to the extent of its

internationalization. Out of 694 companies listed in the Company Index in the Griffin/Pustay (2007)

book, only two companies are cited more frequently than Coca-Cola. It earns more revenues and profits

overseas than in its home country. Moreover, operating in over 197 countries, the company’s main

product, the cola soft-drink, also serves to illustrate a product that is almost the same all across the world.

All in all, as Rugman and Hodgetts’ (1995) analysis of Coke’s various corporate characteristics (e.g.,

production and distribution, strategic orientation, international partnerships, etc.) indicates, the company

may be seen as the quintessential MNE.

5

Coca-Cola, thus, is widely viewed as an example of a company that genuinely illustrates

internationalization in its various forms and serves as an exemplar of international management. We

chose Coca-Cola’s exit from India as a specific issue of interest for our study because the event is

frequently mentioned in a number of IB textbooks as an illustration of the many challenges of doing

international business. Moreover, the example continues to be cited in textbooks even 30 years after the

event suggesting that it has achieved a certain level of acceptance among educators in the field.

Set against the preceding backdrop, our objective in this article is to develop an enhanced critical

understanding of Coca-Cola’s exit from India, as well as of major IB textbooks’ interpretations of that

event. The rest of this article consists of four sections. First, we discuss our use of critical hermeneutics as

the methodology for the present paper. Second, we outline salient details regarding Coca-Cola’s exit from

India, and sketch out how Coke’s exit has generally been interpreted in IB textbooks. Next, we present

our critical analysis of the business situation under consideration and, in so doing, considerably enrich the

current understanding and knowledge about Coke’s exit from India. Finally, we conclude with a brief

discussion of implications.

THE METHODOLOGY OF CRITICAL HERMENEUTICS

During past years, there seems to have been a marked growth of hermeneutics oriented research

in several business-related scholarly fields, such as accounting (Francis, 1994; Llewellyn, 1993), business

communication (Phillips & Brown, 1993; Prasad & Mir, 2002), management information systems (Butler,

1998; Klein & Myers, 1999), marketing (Arnold & Fischer, 1994; Hirschman, 1990), organizational

behavior and theory (Gabriel, 1991; Mercier, 1994), and so forth. In this connection, moreover,

Noorderhaven has pointed out that hermeneutics may well be especially valuable for the field of IB

because the hermeneutic approach “does justice to the challenges formed by the unique character of

international business … as a field” (2004: 84). Noorderhaven (2004: 84) identifies the concept of

distance in its two senses—namely, (a) “the geographical, social, political, economic, cultural and

6

linguistic distance” between the actual actors involved in international business transactions, and (b) the

distance between researchers and their objects of research which invariably involve “a social reality

which is much more distant to them than if they were studying domestic organizations or management

processes”—as indicative of the unique character of the field of international business. At a fundamental

level, therefore, IB research requires a methodology that would help scholars bridge the said distance.

According to Noorderhaven (2004), hermeneutics is precisely such a methodology. The various

methodological elements that enable hermeneutics-oriented research to meaningfully bridge the aforesaid

distance will be outlined below during the course of our discussions in this section of the paper.

Hermeneutics originally emerged as an approach for interpreting complex religious, legal and

literary texts. During recent years, however, hermeneutic scholars have significantly broadened the

meaning of the term, text, to include not only written documents, but also social and economic practices,

culture and cultural artifacts, institutional activities and structures, and so on (Ricoeur, 1971).

Hermeneutics, hence, now serves qualitative/critical management research as a valuable methodology,

allowing scholars to interpret not only documents, but also the much wider range of ‘texts’ spanning a

variety of micro- and macro-level organizational practices and phenomena (Gabriel, 1991; Noorderhaven,

2004; Prasad, A. 2002; Prasad, P. 2005).

Although the origins of hermeneutics may be traced back to ancient Greece, the conceptual

architecture of contemporary hermeneutics has been fashioned primarily by the intellectual efforts of

major modern European philosophers like Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger, Gadamer, Habermas, and

Ricoeur (Bleicher, 1980; Ormiston & Schrift, 1990; Palmer, 1969). Space considerations here do not

permit a detailed discussion of hermeneutics, which may be found in various other sources cited in this

article (e.g., Noorderhaven, 2004; Prasad, 2002). In brief, the hermeneutic approach to interpretation—or,

to be more precise, the critical hermeneutic approach to interpretation—is based upon five major

methodological concepts: (a) hermeneutic circle, (b) hermeneutic horizon, (c) interpretation as dialogue

7

and fusion of horizons, (d) non-author-intentional view of textual meaning, and (e) the significance of

critique in interpretation. Taken together, these five elements enable IB researchers to (1) bridge the

distance which, as we noted earlier, Noorderhaven (2004) has identified as a unique characteristic of

international business, and also (2) allow scholars to develop a critical understanding of the phenomenon

under investigation

The concept of hermeneutic circle proposes that “the part [can only be] understood from the

whole and whole from … its parts” (Palmer, 1969: 77). In other words, any text—such as a corporate

document or an organizational event (“the part”)—can only be understood by situating the said text

within the overall totality of its cultural and historical context (“the whole”), and understanding “the

whole” only takes place by means of understanding the various “parts” that constitute the “whole”. For

management researchers, therefore, the concept of hermeneutic circle emphasizes the crucial importance

of context and history in interpreting any organizational phenomenon. The concept of hermeneutic

horizon, on the other hand, draws attention to the fact that (a) similar to the embeddedness of a text in its

own cultural and historical context, any person undertaking to interpret a given text is likewise embedded

in her/his own context, and (b) that the interpreter’s historico-cultural context is never precisely the same

as that of the text being interpreted (Prasad, 2002; Prasad & Mir, 2002). Hence, according to the

hermeneutic approach, interpreting and understanding a text involves a dialogue (between the text and the

interpreter of the text) that seeks to achieve a fusion and integration of the respective horizons of the text

and that of the interpreter. Such a fusion of horizons “requires … the … suspension of [the interpreter’s

unproductive] prejudices” (Gadamer, 1975: 266).

The nature of hermeneutic interpretation as a fusion of horizons, however, involves also a

profound recognition that the interpretive act is irrevocably rooted in the present, and is necessarily

mediated via the hermeneutic situatedness of the interpreter in the present. According to the hermeneutic

perspective, therefore, interpretation does not imply an attempt to reconstruct or recover the intended

8

meaning of the text’s author. In other words, hermeneutic interpretation subscribes to a non-authorintentional view of meaning, and holds that “the meaning of a text [always] goes beyond its author”

(Gadamer, 1975: 264). The need to critically suspend unproductive prejudices and the rejection of authorintentionality alert us to the importance of the critical dimension in hermeneutics. Hermeneutic

interpretation requires both a self-critical orientation on the part of the interpreter, as well as a critical

stance toward the ‘text’ being interpreted. This aspect of critique in hermeneutic interpretation may

sometimes be facilitated by recourse to various critical scholarly perspectives (e.g., Marxism, neoMarxism, feminism, postcolonialism, etc.), with the result that hermeneutics comes to be transformed into

critical hermeneutics. As already indicated in our introduction, the critical element in the present research

is provided by this paper’s mobilization of insights from the intellectual traditions of political economy as

well as postcolonial theory.

As the foregoing discussion suggests, documents and texts often serve as key data elements in

(critical) hermeneutic research. For purposes of data collection and analysis, we began our study by

scrutinizing a number of popular IB textbooks for references to Coca-Cola’s exit from India. In all, our

research identified 18 textbooks, representing those that have been published by major publishers and/or

have gone through repeated editions. Four textbooks were subsequently dropped from the study because

they had no reference to the Coke exit, leaving 14 textbooks in our final data pool. We then followed up

and accessed the specific citations (newspaper and/or journal references) that the authors of these

textbooks had provided in connection with their discussion of this event. Thereafter, we extended our

document search to the Academic Universe (Lexis/Nexis) data base for references to the Coca-Cola

episode in prominent news sources like the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and Business Week.

Alongside, we also conducted a similar search in the accessible archives of The Hindu, and Times of

India, two of the leading newspapers in India.

9

In order to deepen our understanding of Coke’s exit, we examined India’s FERA legislation

(discussed below). We also undertook a Google Scholar database search of journal articles that mentioned

the subject, and looked at articles dealing with multinationals in Third World countries, as well as articles

that examined exit of MNEs (whether or not such articles specifically referenced the issue of Coke’s exit

from India). In addition, our research also involved interviews with two senior Government of India

officials (now retired)—one from the Ministry of Industry and the other from the Ministry of Finance—

who were responsible for dealing with the Coca-Cola issue in the 1970s.

We wrote to Coca-Cola Company in Atlanta, requesting copies of relevant internal documents. In

their reply, the company’s Executive Counsel stated that “the company does not maintain correspondence

from that time period” in its Atlanta office and will, in due course, try to send any relevant information

the company might still have in its Indian office. However, the company has been unable to send us any

materials thus far and, conceivably, the relevant materials have not been retained in the company’s Indian

office either. Hence, our research mainly confines itself to publicly available materials. In the next section

of the article, we first provide some brief background information about Coca-Cola’s exit from India, and

then review how Coke’s exit has been commonly interpreted in widely-used IB textbooks.

COCA-COLA’S EXIT FROM INDIA

Coca-Cola first began operating in the Indian market in 1956. In 1973, the Indian parliament

passed the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), which came into effect on January 1, 1974. The act

sought to regulate payments and dealings in foreign exchange for the purpose of “conservation of the

foreign exchange resources of the country and the proper utilization thereof in the interests of the

economic development of the country” (FERA, 1973). The various sections of the act laid out rules

relating to who was authorized to deal in foreign exchange, the conditions under which money could be

changed, regulations about making payments in foreign exchange for imports, how money received from

exports was to be accounted for, and so on. Section 29(2)(a) of the Act (and accompanying guidelines)

10

required that foreign companies that owned more that 40% equity in their Indian operations get the

permission of the Reserve Bank of India to continue in business (Nayak, Chakravarthi, & Rajib, 2005).

Four levels of foreign equity participation were permitted under FERA. First, trading companies and

manufacturing companies not using sophisticated technology (e.g., Coca-Cola) were required to restrict

foreign equity holding to 40% of total equity. Second, ‘high-tech’ companies could retain foreign equity

up to a maximum of 74% of the total. Third, multi-activity companies in both high-tech and trading

businesses could retain 51% foreign equity. Fourth, purely export oriented companies were permitted to

retain 100% foreign equity (FERA, 1973; Negandhi & Palia, 1988).

Faced with the stipulations of FERA, some 63 foreign companies in India that did not want to

dilute their equity decided to wind-up operations by 1980-81. In contrast, over 1000 foreign companies

complied with FERA. The Government of India (GOI) allowed majority holdings in the case of over 100

enterprises. Many who chose to stay by diluting equity, where necessary, benefited as it allowed them to

raise fresh capital at a time when access to capital markets was restricted, and also enabled them to raise

market shares (Athreye & Kapur, 2001; Nayak et al., 2005; Subramanian, 2002, 2007).

In accordance with FERA, Coca-Cola Export Corporation (which was 100% US owned and

operated a branch in India) was asked to sell 60% of the equity to Indian nationals. In response, CocaCola made a counter offer stating that two companies be formed: one company with 40% equity to be in

charge of bottling and distribution, and a separate company—termed a technical or administrative unit, in

which the US parent firm would retain 100% equity—to be responsible for importing the concentrate

used in making the soft drink, and to exercise control over the other company. This proposal was found

unacceptable by the GOI. These facts were extensively reported in the press.

Independent of the requirement of dilution of equity, Coca-Cola (along with all other companies

that needed to import materials) was required to obtain every quarter a license to import the concentrate

needed for the soft drink. At about the same time as the equity dilution issue was under negotiation, a new

11

official took charge of the GOI office responsible for approving import licenses. In accordance with

extant government regulations that covered import of food items into the country, he required Coca-Cola

to report to GOI the specific ingredients used in the concentrate and/or have the product safety tested in

the government food laboratories as a condition for grant of import license. Coca-Cola refused to do so

(Mahadevan, 2007). The company then decided to withdraw from India.

Current Interpretations of Coca-Cola’s Exit from India

Our review of existing interpretations of Coca-Cola’s exit draws upon discussions of the event

appearing in a set of 14 popular IB textbooks widely used in the United States and elsewhere. In general,

IB textbooks aim to provide a causal explanation for Coke’s exit, and often frame their discussions

around certain concerns the firm is said to have had about losing its secret formula for the Coca-Cola

concentrate. For instance, according to Wild, Wild and Han (2010), “Coca-Cola … left India when the

[Indian] government demanded that it disclose its secret formula as a requirement for doing business” in

India (p.329). Similarly, Peng (2009) asserts that the company withdrew because the “Indian government

… demanded that Coca-Cola share its secret formula” (p.161), and Holt and Wigginton (2002) declare

that the company exited from the Indian market because “India attempted to gain access to Coke’s highly

guarded formula for its syrup” (p.75). Likewise, Griffin and Pustay (2007:43) argue that:

“… as a condition for remaining in the country, the Coca-Cola company was retroactively

required in the 1970s to divulge its secret soft drink formula. Coca-Cola refused and chose to

leave the market.”

Somewhat distinct from the aforementioned accounts, which seek to portray Coke’s withdrawal as a fairly

direct result of GOI’s demand that the company share its concentrate’s secret formula, other textbooks

offer an explanation for Coca-Cola’s exit that relies more upon the FERA requirement for dilution of

foreign equity and the supposed risks such dilution posed for the company’s intellectual property rights

involving its secret concentrate formula. For instance, Deresky (2006:318) argues that:

12

“In the regulatory environment of the late 1970s, foreign companies operating in any non-priority

sector in India could not own more than 40% stake in the venture. Coca-Cola ran its operations

through a 100% subsidiary. After the company refused to partner with an Indian company and

share its technology it had to stop its operations and leave the country” (emphasis added).

Similarly, Hill (2011a: 84; 2011b:79) provides the following clarification for Coke’s exit:

“… in the 1970s when the Indian government passed a law requiring all foreign investors to

enter into joint ventures with Indian companies, US companies … [like] Coca-Cola closed their

investments in India. They believed that the Indian legal system did not provide for adequate

protection of intellectual property rights, creating the very real danger that their Indian partners

might expropriate … intellectual property…” (emphasis added).

In other words, authors like Deresky (2006) and Hill (2011a&b) do not make the argument that CocaCola withdrew from India because the GOI demanded that the company divulge Coke’s secret formula.

Rather, their contention seems to be that GOI enacted new legislation (namely, FERA) requiring CocaCola to reduce its foreign equity and enter into joint venture with an Indian firm, and that Coca-Cola was

unwilling to do so because partnering with an Indian firm put Coke’s secret formula at risk. Explanations

that follow this line of reasoning are offered also by some other textbooks (e.g., Czinkota, Ronkainen, &

Moffett, 2005; Punnett & Ricks, 1997), as well as by certain scholarly articles (e.g., Encarnation &

Vachani, 1985). Tallman (2009:30) refers to a ‘loss of proprietary resources’ for the company. In our

review, Hodgetts, Luthans & Doh (2006:32) stood out from the other textbooks by referring to the exit as

having been caused by ‘a change of rules’ in the country and not providing any interpretation.

In certain cases, the aforesaid explanations are accompanied by references to specific reports

published in US newspapers during the 1970s that seem to support the textbooks’ contentions. A

representative sample of those newspaper reports is given below.

Wall Street Journal (Editorial, August 10, 1977): “… [the Government of India demanded that]

… Coca-Cola deliver the secret of 7X [beverage concentrate]…”

New York Times (August 25, 1977): “The Government [of India] has asked Coca-Cola to

surrender its secret syrup formula to an Indian-controlled concern or get out by next April.”

New York Times (August 31, 1977): “… Indian Government demands … a controlling interest in

the company and … full disclosure of the soft drink formula so that Indian manufacturers can

produce the beverage.”

13

New York Times (September 5, 1977): “… the Company [is required to] … transfer … the

formula for its concentrate to Indian shareholders or cease operations in India.”

In sum, IB textbooks’ explanations for Coke’s exit do seem to run in tandem with US newspaper accounts

published at the time, that contend that Coca-Cola withdrew either because (a) the GOI demanded that the

company reveal its secret concentrate formula, or (b) because the GOI demanded that the company dilute

its equity to 40% of total, and become a junior partner in a joint venture with an Indian firm that would

hold the remaining 60% equity.

At this juncture, it becomes important for purposes of analysis to pay close attention to some of

the finer empirical details of the business situation under consideration. When we do so, we find that the

two basic assumptions—namely, (a) GOI’s alleged demand for the secret concentrate formula and (b)

GOI’s supposed requirement that Coca-Cola become a junior partner in a joint venture—which provide

the foundation for various accounts appearing in US newspapers as well as IB textbooks, are unwarranted

and cannot be justified. A careful examination of the empirical details indicates that (a) the GOI neither

demanded the secret concentrate formula for itself nor did GOI insist that an Indian partner be given the

formula, and (b) that the GOI did not require Coca-Cola to become a junior partner: in other words, the

60% equity required to be held by Indian shareholders as per FERA could be widely dispersed among the

Indian public, leaving effective control in the hands of Coca-Cola (Encarnation & Vachani, 1985; FERA,

1973; Negandhi & Palia, 1988; Mahadevan, 2007; Subramanian, 2007).

Clearly, therefore, many popular textbooks’ explanations of Coke’s exit seem to rely upon

mistaken statements of important ground-level facts and, as a result, may be seen as seriously limited.

However, in addition to recognizing the significance of such errors, we can develop deeper insights into

the limitations of the IB textbooks’ interpretations by examining the somewhat restricted way in which

these textbooks tend to define the context for their analysis of the event. As noted earlier, hermeneutics

emphasizes the importance of overall context and history for purposes of adequately interpreting

14

organizational activities. From the hermeneutic perspective, therefore, IB textbooks’ interpretations are

rather limited because these textbooks invariably choose to proceed with their analysis within a narrowly

defined context, specifically, only the context of political and regulatory changes taking place in India at

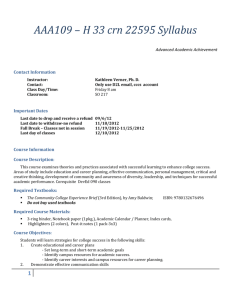

that time. Table 1 summarizes our analysis of the ways in which major IB textbooks portray Coke’s exit.

______________________

Place Table 1 about Here

______________________

Table 1 identifies (a) the specific chapters and/or major sections, as well as (b) the sub-section

and/or paragraph under which popular IB textbooks generally place their discussions of this incident. As

the table indicates, these textbooks mostly locate Coca-Cola’s exit within the context of the regulatory or

political environment of the country, the changes occurring within this environment, and the risks such

changes might pose for foreign firms. Once the context has been so defined, the explanations being

offered by the textbooks follow certain specific trajectories. These include claims like Coke withdrew

from India because of (a) GOI’s demand for the secret concentrate formula, or (b) as a result of a new

GOI requirement that all foreign investors enter into joint ventures with Indian companies, or (c) owing to

the emergence of some new risk close to that of nationalization/expropriation of assets, or (d) on account

of political blackmail, or (e) due to corruption and political avarice in India, or (f) in consequence of lax

intellectual property rights (IPR) protection under Indian legal conditions, and so on (Table 1).

We have already noted that the first two claims in the preceding list cannot be supported on the

basis of empirical details relating to the event. But what about some of the other claims? For instance, did

the GOI’s actions amount to some kind of attempted nationalization, as Peng’s (2009) textbook suggests

when it observes: “Coca-Cola’s experience in India is not isolated. Numerous governments in Africa,

Asia and Latin America have expropriated assets through nationalization” (p.161). Or did the GOI’s

actions amount to political blackmail, and was there corruption involved? Holt and Wigginton (2002: 75)

15

assert that the GOI’s action “was called a blatant form of political blackmail”, but do not provide the

necessary reference to a source. The same authors’ discussion alludes also to “corruption or political

avarice” (Holt & Wigginton, 2002: 75). And was IPR protection inadequate in India? Indian laws seem to

have been in conformity with the global IPR regime prevailing at the time but, in view of recent changes,

the old regime might be seen as insufficient by some.

Irrespective of the actual substance of many of these claims, however, what is clear is that IB

textbooks generally tend to regard the Indian political/regulatory environment as a key problem. Not

surprisingly, perhaps, this tendency can sometimes result in unjustifiable claims being made. For instance,

viewing the regulatory changes of that time as a major problem, Shenkar and Luo (2004: 185) assert that

those changes led to an “exodus of … foreign MNEs” from India (emphasis added). As noted earlier,

following the enactment of FERA, 63 or so foreign MNEs withdrew from India while more than 1000

foreign companies stayed in the country: not exactly an ‘exodus’. However, Shenkar and Luo’s inference

of an ‘exodus’ is plausible if the starting point of analysis is the assumption that FERA, inherently, was a

significant problem and was viewed as such by an overwhelming number of foreign MNEs.

However, rather than attempting to either substantiate or refute various claims documented

above—a somewhat fraught enterprise, in any case, in view of the nature of some of the claims—it might

be useful to examine the persistent tendency in IB textbooks to interpret Coke’s exit only as a result of

problems/inadequacies/risks that are said to characterize India’s political/regulatory environment. What

could be some of the implications of this tendency? What might account for the tendency to see India’s

political/regulatory environment as beset by serious problems? How might our understanding of the event

shift if we decide to move away from the limited way in which IB textbooks define the context for their

analysis? The next section of the article addresses some of these issues and, in so doing, seeks to develop

an enhanced critical understanding of Coca-Cola’s exit from India.

TOWARD A CRITICAL UNDERSTANDING OF COCA-COLA’S EXIT

16

One of the important motivations driving the present study is the desire for a more comprehensive

and critical understanding of Coca-Cola’s exit from India. With that end in view—and in line with (a) the

concept of hermeneutic circle, which holds that interpretation emerges via a circular movement between

‘text’ and ‘context’, and (b) the notion of interpretation as a fusion of the hermeneutic horizons of the

‘text’ and of the interpreter—it is necessary to define the context for our analysis at multiple levels of

increasing comprehensiveness and, in so doing, to work toward expanding and broadening our own

hermeneutic horizons (Gadamer, 1975; Noorderhaven, 2004; Prasad, 2002).

Hence, in this section of the article, we will move beyond the limited context of proximate

political/regulatory environment (within which IB textbooks’ discussions of Coke’s exit are commonly

confined), and develop a more broad-based, inclusive, nuanced and critical understanding of Coca-Cola’s

exit from India. In particular, our analysis will focus upon the following three broader levels of context:

(a) the larger macro-economic context of India during the 1970s, (b) the longer-term historical context of

India’s economic development, and (c) the cultural context as regards the place occupied by India within

wider Western/American consciousness. Moreover, while the first two levels of context—which are

primarily economic in nature—will be analyzed in this paper from a scholarly vantage point largely

located in the domain of political economy, our analysis of the third (i.e., cultural) level of the broader

context will also draw upon Edward Said’s (1978) contributions to postcolonial theory. In what follows,

we will briefly outline some of the key aspects of each of these higher levels of context, and analyze the

significance of such broadened delineation of context for enhancing our understanding of Coca-Cola’s

exit.

Indian Macro-Economy during the 1970s

The FERA legislation (discussed earlier) had been enacted under a general situation of

deteriorating macro-economic conditions in India. The first half of the 1970s was marked by serious

economic difficulties for India: average annual GDP growth rate, which had registered 4.8% during 1966-

17

1971, fell precipitously to 3.3% during 1971-1976 (Nayar & Paul, 2003). This steep decline was triggered

by a number of factors, including the economic burdens relating to the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 and the

influx of some 10 million refugees into India from Pakistan, as well as the dramatic escalation of oil

prices by OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) in 1973. Developments like these

resulted in deep problems for the Indian economy and, in particular, created grave strains on the foreign

exchange resources of the country.

In the early 1970s, the developing shortage of foreign exchange led to considerable policy

emphasis on import restriction/substitution and export promotion, and serious concerns were expressed

about large amounts of foreign exchange flowing out of the country owing to foreign MNE operations

involving payments for imports as well as repatriation of dividends. This was also a time when different

aspects of MNE behavior in developing markets (e.g., shipping of old technology, employing only

expatriates at managerial levels, monopolistic practices, etc.) led to a generalized reputation of MNEs as

being exploitative. Governments of many developing countries argued that there was a genuine need to

control and regulate MNEs in order to encourage the growth of indigenous business enterprises. These

sentiments were shared by significant sections of Indian policy makers. The enactment of FERA took

place within these very developments involving a deteriorating economy, growing foreign exchange

shortage, and increasing antipathy toward foreign MNEs.

When we broaden the context to include India’s macro-economy during the 1970s, it becomes

possible to recognize FERA as GOI’s response to a specific problem (namely, escalating foreign

exchange shortages), and move beyond the tendency displayed by IB textbooks to consider this

legislation itself as the problem, and as a mere manifestation of GOI’s desire to increase control over

MNEs. In other words, understanding the macro-economic context helps us realize that regulatory

changes of the period were intended to address a serious economic problem, rather than simply increase

GOI’s control over MNEs merely for the sake of greater control. Indeed, the fact that FERA itself

18

permitted majority foreign equity holding for specific categories of MNEs suggests that control, on its

own, need not be seen as the guiding objective of this legislation. Moreover, this element of FERA also

helps us understand that exit was not Coke’s only option under the situation; with somewhat greater

ingenuity and flexibility, the company had a range of options for continuing its operations in India. These

aspects of the situation, however, tend to be ignored in IB textbooks’ interpretations because of their

limited definition and understanding of the overall context.

Interestingly, Encarnation and Vachani (1985) have examined how a set of MNEs responded to

FERA. Their analysis points out that, rather than quitting like Coca-Cola, those firms that continued

operating in India often benefited through protected markets, succeeded in lowering capital costs by

improving the equity base, continued to retain control through wide distribution of new equity, and

entered into useful diversification of business. From this perspective, Coca-Cola, while undoubtedly a

company faced with changes in the political/regulatory environment, may also be seen as a company that

lost an opportunity due to somewhat inflexible corporate policies.

The Historical Context of India’s Economic Development

In the 1750s, when Britain began its century-long process of Indian conquest, India’s economy

produced roughly 25% of total global output; by the time India won back its independence in 1947, the

Indian economy accounted for just about 2% of the global economy (Huntington, 1996). This

extraordinary collapse of Indian economy between the 18th and 20th centuries was the result of a policy of

Indian de-industrialization, economic neglect, and colonial plunder pursued by Britain (Guha, 2007). It is

interesting to note, moreover, that Britain’s conquest of India was largely accomplished by a private

company, the East India Company.

After independence, the country sought to reverse its long economic decline, and the GOI

assumed a key role in directing Indian economic development by instituting a system of centrally-

19

coordinated national economic planning. This model of planned economic development yielded positive

results and the country’s annual GDP growth rate, which had stagnated under 1% before independence,

climbed to an average of about 4.8% during the period 1966-1971 (Nayar & Paul, 2003). The Indian

model of economic development emphasized the creation of a significant industrial base for the country,

with particular focus upon heavy industries, development of scientific and technological capabilities, and

economic self-reliance (Guha, 2007; Nayar & Paul, 2003). Moreover, partly in view of certain conditions

unique to India, the GOI decided also that the public sector would assume direct responsibility for

industrial development in many strategically important sectors of the economy.

Despite its focus on the public sector, the Indian developmental model also involved a significant

role for the private sector. Hence, it needs to be emphasized that the Indian model of a mixed economy

(i.e., a mix of public and private sectors) was substantially different from the economic model adopted by

“communist” countries like the erstwhile USSR, which prohibited private enterprise altogether. In pursuit

of its policy of developing a mixed economy, the GOI classified industries into different categories, some

of which (e.g., atomic energy, defense, etc.) were reserved for the public sector, others (e.g., chemicals,

pharmaceuticals, etc.) that were open to both sectors, and yet others (e.g., consumer products, food, soft

drinks, etc.) that were generally for the private sector alone. Coca-Cola Company, hence, operated in a

sector of the economy in which the GOI, by virtue of its explicitly-stated policy, had little interest in

promoting public sector ownership. On the other hand, in several other industries (e.g., banking,

insurance, coal, petroleum, etc.) the GOI promoted significant public sector participation including, where

necessary, nationalization of private sector enterprises.

This overview of the historical context is useful for deepening our understanding of the event.

Among other things, the historical context helps us develop a better appreciation of the role of

nationalization in India’s economic policy. Specifically, it appears that nationalization, while indeed an

important part of the Indian model, was generally confined to sectors of considerable strategic

20

importance. Therefore, there would seem to be little justification for interpreting Coke’s Indian

experience as being parallel to that of a firm being nationalized, unless the analyst assumes that a soft

drink company was a company of strategic significance for India’s economy in the 1970s. Such an

assumption, however, is difficult to sustain in light of the relative sophistication achieved by the Indian

economy by the 1970s. Hence, Peng’s (2009) conclusion that Coke’s experience in India has its parallel

in various acts of expropriation of MNE assets in “Africa, Asia and Latin America” (p.161) does not seem

tenable.

Moreover, the historical context also draws attention to the fact that FERA’s differential

treatment of different types of industries (e.g., priority, non-priority, etc.) was broadly in step with the role

accorded to different categories of industries in India’s post-Independence economic policy. Hence, GOI

appears to us in the form of a rational actor taking actions that are broadly consonant with a long-term

policy set in place at Independence. For such an actor to be engaging in “political blackmail” to get the

formula for a soft-drink syrup—as Holt and Wigginton (2002) suggest—seems somewhat improbable.

What this suggests is that researchers may need to steer clear of interpretations that view Coke’s exit as a

response either to increased risk of nationalization or alleged political blackmail.

India in Western Cultural Consciousness

Recent postcolonial theoretic scholarship in a range of academic fields, including IB, has pointed

out that Western cultural perceptions of the Third World have been significantly shaped by the long

history of European colonial domination of the world (Jack & Westwood, 2006; Özkazanç-Pan, 2008;

Prasad, 2003). For instance, Said (1978) has drawn attention to the ideological discourse of

‘Orientalism’—developed in tandem with European colonial expansion—as a key influence in molding

Western cultural understandings of various Eastern countries and regions. According to Said (1978),

‘Orientalism’ as a Western ideological discourse provides an epistemological framework, as well as a

cultural “style of thought” (p.2), that systematically regards (a) the East and the West as binary opposites,

21

(b) considers the West as superior to the East, (c) views the East as a constant source of danger, and (d)

perceives the East to be weighed down by a host of negative attributes such as backwardness, corruption,

irrationality, lawlessness, and the like.

Not surprisingly, views like these have long circulated in the United States as well, and have

deeply conditioned American cultural perceptions of the Third World, including those about India. For

instance, President Theodore Roosevelt himself wrote glowingly about British colonization of India as

“one of the mighty feats of civilization, one of the mighty feats to the credit of the white race” (Roosevelt

quoted in Nayar & Paul, 2003: 94-95) and, for various reasons, the United States was not at all

“enthusiastic” about India’s independence (Nayar & Paul, 2003: 67). Moreover, barring brief

improvement during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the place occupied by India in American/Western

cultural consciousness seems to have significantly deteriorated after Indian independence (Nayar & Paul,

2003).

Considerations of space prevent us from discussing various developments (e.g., Indian economic

policies, Cold War geo-politics, Vietnam War, etc.) that apparently contributed toward the aforesaid

deterioration (Guha, 2007; Nayar & Paul, 2003). In any event, American/Western cultural understanding

of India after India’s independence was set on a path of steady decline; Western media reports largely

offered unfavorable views of Indian economy, society and politics; and America and the West generally

came to see only “the bleak side of India” (Nayar & Paul, 2003: 97).

Hence, by the first half of the 1970s, India seems to have become entrenched in

American/Western cultural consciousness in a rather negative light. This was reflected in the way India

came to be portrayed in Western textbooks, media, and scholarly writings. Indeed, the prestigious Asia

Society’s review of 300 textbooks being used in US schools during 1974-1975 revealed that the

textbooks’ depiction of India “was the most negative of all Asian countries” (Asia Society, 1976; quoted

in Nayar & Paul, 2003: 95). The stereotypical depictions of India at the time included representations of

22

India as a land of rampant corruption, political turmoil, disorder and absence of rule of law, underdevelopment and economic failures, and as a country that was mystical and ‘other-worldly’ but also ‘soft’

on “communism” (Guha, 2007).

Expanding the context of our analysis to encompass elements of the wider Western cultural

consciousness is useful for further enhancing our understanding of Coke’s exit. Noorderhaven (2004)

notes that adopting the hermeneutic perspective in IB research implies that “practitioners of international

business … [need to be] regarded as [practicing] hermeneuticians” (p.96). This entails the necessity of

understanding international managers’ interpretations of the external environment and the business

situation they are confronted with. We suggest here that recognizing the mediating influence of Western

cultural consciousness on Coca-Cola’s managers’ interpretations of the external environment in India

helps us gain deeper insights into the firm’s decision to withdraw from the country.

For instance, the Western cultural view of India as a country where there is absence of rule of law

implies that its government might be seen as prone to taking capricious actions. Hence, as far as CocaCola is concerned, the letter and spirit of any law (e.g., India’s IPR law) loses its sanctity, and the

company’s decisions would likely be mediated by the belief that it cannot rely upon Indian courts of law

to uphold its legitimate IPR relating to the syrup formula. Similarly, if India is culturally seen as

economically ‘irrational’—or as a country where “politics often prevailed over economic interests,” to

quote the Rugman and Hodgetts (1995: 554) textbook—then Coca-Cola would likely believe that

conducting reasonable discussions and negotiations with the GOI might be exceedingly difficult.

Likewise, to the extent that Coca-Cola’s managers saw India as “socialistic”, they likely regarded

nationalization to be an uncompromising ideological goal for the Indian government and, moreover, they

might have been highly apprehensive that the GOI could arbitrarily expropriate the company’s assets

without due compensation.

23

Once we factor in the mediating role of the aforesaid cultural consciousness, it may no longer be

a matter of surprise that the GOI’s requirement that the concentrate be made locally in India was

interpreted by Coca-Cola as attempted expropriation of the company's intellectual property; sale of equity

to the Indian public was interpreted as handing over control to a majority Indian partner; and the GOI

requiring a detailing of the drink’s ingredients for food safety testing purposes was interpreted as the

government requiring that the concentrate formula be divulged. In sum, the cultural lens provided by

stereotypical Western understandings of India likely helped create within the Coca-Cola Company an

amplified perception of political/regulatory risk and, consequently, exit from India came to be seen as the

only viable option for the firm. Indeed, such stereotypical understandings may be said to have played an

important role also in the various newspaper accounts and textbook discussions.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have sought to develop a more critical and comprehensive understanding of

MNE operations and national governments through an analysis of Coca-Cola’s exit from India during the

1970s, and in this process, also provided a critical revision of popular Western IB textbooks’

interpretations of this event. Current IB textbooks seem to contend not only that (a) the company

withdrew because of increased risks/problems in India’s political/regulatory environment in those years,

but also (b) that Coke might have been left with no option other than to quit the Indian market. In other

words, IB textbooks make the case that the company’s decision was strategically correct. Our critical

analysis, on the other hand, questions the interpretation offered in mainstream IB textbooks, and proposes

that the option to exit from India was not the only option available to the firm, and that in deciding to quit,

the company could also be said to have lost a valuable opportunity as a result of inflexible policies.

It needs to be noted, moreover, that Coca Cola’s re-entry into India in 1993—pursuant to the

liberalization of the Indian economy in 1991—seems to have been seen in certain quarters as a further

vindication of the narrow managerialist interpretation of the firm’s exit offered in IB textbooks. Our

24

critical re-examination of the record, hence, provides an important corrective, suggesting that Coke’s exit

from India in the 1970s needs to be viewed as having been significantly mediated by elements of Western

cultural consciousness, combined with an inadequate appreciation of India’s broader macro-economic and

long term historical contexts.

This study has a number of important implications for management and international business. To

begin with, the study emphasizes the crucial significance of history and the wider economic, political, and

cultural context for developing a more complete and informed understanding of organizational actions,

processes, events and so forth. As this paper has sought to demonstrate, current IB textbooks’

interpretations of Coke’s exit turn out to be inadequate largely as a result of those textbooks’ decision to

focus exclusively on the immediate context of political/regulatory changes in India, and to summarily

ignore important aspects of wider context and history. Management and IB researchers, hence, need to

recognize that developing a comprehensive and well-rounded understanding of organizational phenomena

requires that such phenomena be seen as deeply embedded in much larger contexts and histories.

However, it needs to be emphasized here that becoming familiar with the larger contexts and

histories of organizational phenomena is not an easy task, particularly for those IB scholars who may be

required to have dealings in their research with different countries having widely divergent cultures,

histories, local categories for configuring the social world, “modes of organizing” (Ibarra-Colado, 2006:

474), and so on. Following Spivak (2003), we would like to suggest that becoming familiar with the

broader context and history of a country/culture different from one’s own requires serious effort aimed at

developing an ‘idiomatic understanding’ of the country/culture in question. Such an ‘idiomatic

understanding’—which may often necessitate extended intellectual preparation directed at learning that

‘other’ society’s culture, history, politics, language(s), and so on—requires also a deep commitment to

non-Eurocentric thinking, and genuine respect for difference. Consequently, we believe that developing

the kind of understanding suggested above may be especially difficult for Western IB scholars for a

25

variety of reasons including, for instance, the pressures of a ‘publish or perish’ academic ‘research

industry’, as well as the Eurocentrism and provincialism that seem to pervade large sections of Western

culture and academe (Prasad, 2003, 2012; Said, 1978; Spivak, 1999). This implies that Western IB

scholars may need an extra degree of caution and considerable added effort while conducting research

that deals with non-Western countries and cultures.

Our paper also suggests the need for a concerted program of IB research designed to critically

revisit all other present and/or future business cases (especially, perhaps, the cases dealing with ‘Third

World’ countries) in mainstream IB textbooks. This paper has examined the limitations of IB textbooks in

the context of only one single case. Many other similar studies, however, are needed to fully cover the

spectrum of business cases discussed in IB textbooks. Such a program of critique is necessary not only for

underscoring the need for much greater scholarly rigor and caution in contemporary IB research, but also

for pedagogical purposes. Briefly stated, this kind of critical examination of business cases would seem to

be essential for alerting students to be on guard against the Eurocentrism and other limitations of IB

textbooks, and for adequately preparing today’s business students for a rapidly globalizing and

transforming world.

Kuhn (1970), in his analysis of history of science, points out that textbooks in their descriptions

of theories and concepts establish a paradigm that serves the purpose of normal science for a while,

explaining events and allowing for interpretation, till a new scientific revolution challenges the

established paradigm. Similarly, it could be argued that mainstream IB textbooks in the West adhere to a

particular paradigm of MNE operations in the ‘Third World’, and viewed Coke’s exit from India through

the prism of that particular paradigm. As suggested in our discussion, Said’s (1978) notion of Orientalism

appears to be an important element of that paradigm, under which alleged political risks and dangers in

the Third World are often viewed as compelling triggers for MNE behavior. Our analysis, however,

suggests that a more comprehensive understanding of context might be valuable in developing a relatively

26

moderate assessment of such perceived threats. Our study, hence, has certain parallels with studies of

government intervention in ‘Third World’ countries, which argue for the need to develop a nuanced

notion of ‘political risk’ and to look at the perspective of governments involved (e.g., Makhija, 1993;

Poynter, 1982).

In the process of examining IB textbooks, we found certain errors relating to statements of

empirical details surrounding Coke’s exit. We were able to ascertain one possible source of those errors,

namely, newspaper reports cited by the authors. In addition, similarities in comments across some

textbooks lead us to speculate as to one more plausible explanation for recurring errors. Loewen’s (1995)

analysis of persistence of errors in US history textbooks suggests that one author often takes her/his cue

from another, and the same (or similar) erroneous statements survive and continue to circulate through

future textbooks. It is possible that a similar dynamic might have obtained also in the case of IB textbooks

examined in our study.

It might be useful here to comment also on the role of textbooks in knowledge creation.

Textbooks are an attempt to bridge the gap between theory and practice when they provide description of

theory and examples to illustrate the theory. In this process, however, apart from playing a role in

transmitting knowledge, they may also be seen as creating knowledge, and by their choice of illustrations

and description of events, promoting/establishing a certain view of the world. Authors of textbooks

always seek to provide examples to illustrate the concepts being discussed. This can be an extremely

difficult task when writing on international topics since these often deal with countries, cultures and

contexts with which the authors may have little or no familiarity.

There is, thus, need for great care in choice of illustrations and comments. It is easy enough for

errors to persist and seemingly take a life of their own, as shown by Tipton (2008) who found persistent

errors on the topic of cultural difference in 19 widely used IB textbooks. Harzing (2002), in her review of

referencing errors in general, and references to her expatriate study in particular, comments that textbooks

27

and professional journals should be expected to maintain academic standards of citation and referencing.

Harzing cautions us that the implications of inaccurate referencing are serious for academics and

practitioners alike. For instance, certain reports from 2002 claiming that Coke was ‘banned from India’ in

the 1970s may be seen as continuing, even after a lapse of several years, the rather limited understanding

of the event. This suggests the need for considerable self-reflexivity on the part of authors of IB

textbooks.

28

REFERENCES

Arnold, S., and Fischer, E. (1994) ‘Hermeneutics and consumer research’, Journal of Consumer

Research 21: 55-70.

Asia Society. (1976) Asia and American Textbooks. New York: Asia Society.

Athreye, S. and Kapur, S. (2001) ‘Private foreign investment in India: Pain or Panacea’, The World

Economy 24(3): 399-424.

Bleicher, J. (1980) Contemporary hermeneutics. London: Routledge.

Butler, T. (1998) ‘Towards a hermeneutic method for interpretive research in information systems’,

Journal of Information Technology 13: 285-300.

Chari, S., & Verdery, K. (2009). Thinking between the posts: Postcolonialism, postsocialism, and

ethnography after the Cold War. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 51(1): 6-34.

Coronado, G. (2012) (forthcoming). Constructing the neocolonial manager: Orientalizing Latin America

in the textbooks. In A. Prasad (ed.), Against the grain: Advances in postcolonial organization

studies. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Cummings, S. & Bridgman, T. (2011). The relevant past: Why history of management should be critical

for our future, AOM Learning & Education, 10(1): 77-93.

Czinkota, M. R., Ronkainen, I. A., and Moffett, M. H. (2005) International Business, 7ed. Ohio:

Thomson/Southwestern.

Daft, R. and MacIntosh, N. (1981) ‘A tentative exploration into the amount and equivocality of

information processing in organizational work units’, Administrative Science Quarterly 26: 207224.

29

Deresky, H. (2006) International Management, 5ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Encarnation, D. J. and Vachani, S. (1985) ‘Foreign ownership: when hosts change the rules’, Harvard

Business Review 63(5): 152-160.

FERA (1973) Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973, (Act 46 of 1973), Government of India, New

Delhi.

Fougère , M. & Moulettes , A.. (2011). Disclaimers, dichotomies and disappearances in international

business textbooks: A postcolonial deconstruction, Management Learning, Published online

before print May 31, 2011, doi: 10.1177/1350507611407139.

Francis, J.R. (1994) ‘Auditing, hermeneutics, and subjectivity’, Accounting, Organizations and Society

19: 235-269.

Frank, V. H. (1984) ‘Living with price control abroad’, Harvard Business Review 62: 137-142.

Gabriel, Y. (1991) ‘Turning facts into stories and stories into facts: A hermeneutic exploration of

organizational folklore’, Human Relations 44: 857-875.

Gadamer, H-G. (1975) Truth and Method. New York: Seabury Press.

Griffin, R. W. and Pustay, M. W. (2007) International Business, 5ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Prentice Hall.

Guha, R. (2007) India after Gandhi. New York: HarperCollins.

Harzing, Anne-Will, (2002). ‘Are our referencing errors undermining our scholarship and credibility? The

case of expatriate failure rates’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 23, 127-148.

Hill, C. W. L. (2011a) Global Business Today, 7ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Irwin.

30

Hill, C. W. L. (2011b) International Business: Competing in the Global Marketplace, 8ed . NY:

McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Hirschman, E.C. (1990) ‘ Secular immortality and the American ideology of affluence’, Journal of

Consumer Research 17: 31-42.

Hodgetts, R. M., Luthans, F. and Doh, J. P. (2006) International Management, 6ed. NY: McGraw Hill.

Holt, D. H. and Wigginton, K. W. (2002) International Management. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College

Publishers.

Huntington, S. (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York:

Simon & Schuster.

Ibarra-Colado, E. (2006). Organization studies and epistemic coloniality in Latin America. Organization,

13: 463-488.

Jack, G., and Westwood, R. (2006) ‘ Postcolonialism and the politics of qualitative research in

international business’, Management International Review 46: 481-501.

Jack, G., Westwood, R., Srinivas, N., & Sardar, Z. (2011). Deepening, broadening and re-asserting a

postcolonial interrogative space in organization studies. Organization, 18(3): 275-302.

Klein, H. and Myers, M. (1999) ‘A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field

studies in information systems’, MIS Quarterly 23: 67-93.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lazarus, N. (Ed.). (2004). The Cambridge companion to postcolonial studies. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

31

Llewellyn, S. (1993) ‘Working in hermeneutic circles in management accounting research’, Management

Accounting Research 4: 231-249.

Loewen, J. W. (1995) Lies My Teacher Told Me. New York: The New Press.

Loomba, A., Kaul, S., Bunzl, M., Burton, A. & Esty, J. (Eds.). 2005. Postcolonial studies and beyond.

Durham: Duke University Press.

Mahadevan, I. (2007) Former Joint Secretary, Industrial Licensing and Joint Secretary, Consumer

Industries, Ministry of Industry, Government of India. Personal interview on 19 August.

Makhija, M. (1993) ‘Government intervention in the Venezuelan petroleum industry: An empirical

investigation of political risk’, Journal of International Business Studies 24(3): 531-555.

McLaren, P. G., Durepos, G. & Mills, A. J. (2009). Disseminating Drucker: Knowledge, tropes and the

North American management textbook, Journal of Management History, 15(4): 388-403.

Mercier, J. (1994) ‘Looking at organizational culture, hermeneutically’, Administration & Society 26: 2847.

Nayak, A. K. J. R., Chakravarti, K., and Rajib, P. (2005) ‘Globalization process in India: A historical

perspective since independence, 1947’, South Asian Journal of Management 12(1).

Nayar, B. and Paul, T. (2003) India in the World Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Negandhi, A. R. and Palia, A. P. (1988) ‘Changing multinational corporation – Nation State relationship:

The case of IBM in India’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management 6(1): 15-38.

New York Times (1977) ‘India stands firm against Coca-Cola’, September 5: 22.

New York Times (1977) ‘India to honor US commitments despite problems with Coca-Cola’, August 31:

66.

32

New York Times (1977). ‘India chooses ‘77’ name for its Coke substitute’, August 25: 76.

Noorderhaven, N. G. (2000) ‘Positivist, hermeneutical and postmodern positions in the comparative

management debate,’ in M. Maurice and Sorge, A. (eds), Embedding organizations: Societal

analysis of actors, organizations and socio-economic context, p. 117-137. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Noorderhaven, N. G. (2004) ‘Hermeneutic methodology and international business research’, in

Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for

International Business, p. 84-104. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Ormiston, G., and Schrift, A. (eds.) (1990) The hermeneutic tradition. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Ozkazanc-Pan, B. (2008) ‘International management research meets ‘the rest of the world’, Academy of

Management Review 33: 964-974.

Palmer, R.E. (1969) Hermeneutics: Interpretation theory in Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger, and

Gadamer. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Peng, M. W. (2009) Global Strategy, 2ed. Mason, Ohio: Cengage/Southwestern.

Peng, M. W. (2011) Global Business. Mason, Ohio: Cengage/Southwestern.

Phillips, N., and Brown, J. (1993) ‘Analyzing communication in and around organizations: A critical

hermeneutic approach’, Academy of Management Journal 36 (6): 1547-1576.

Poynter, T. (1982) ‘Government intervention in less developed countries: The experience of multinational

companies’, Journal of International Business Studies 13(1): 9-25.

Prasad, A. (2002) ‘The contest over meaning: Hermeneutics as an interpretive methodology for

understanding texts’, Organizational Research Methods 5(1): 12-33.

33

Prasad, A. (2003) Postcolonial Theory and Organizational Analysis. New York: Palgrave.

Prasad, A. (2012) (forthcoming). Working against the grain: Beyond Eurocentrism in organization

studies. In A. Prasad (ed.), Against the grain: Advances in postcolonial organization studies.

Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Prasad, A. and Mir, R. (2002) ‘Digging deep for meaning: A critical hermeneutic analysis of CEO letters

to shareholders in the oil industry’, Journal of Business Communication 39(1): 92-116.

Prasad, P. (2005) Crafting qualitative research: Working in the postpositivist traditions. Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

Punnett, B. J. and Ricks, D. A. (1997) International Business, 2 ed. Cambridge MA: Blackwell.

Ricoeur, P. (1971) ‘The model of the text: Meaningful action considered as a text’, Social Research 38:

529-562.

Rugman, A. and Hodgetts, R. M. (1995) International Business. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Said, E. W. (1978) Orientalism. New York: Random House.

Shenkar, O. and Luo, Y. (2004) International Business. NY: John Wiley.

Spivak, G. C. 1999. A critique of postcolonial reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Spivak, G. C. 2003. Death of a discipline. New York: Columbia University Press.

Subramanian, K. (2002) ‘ Coca-Cola's continuing saga on equity’, The Hindu, 10 June, p. 16.

Subramanian, K. (2007) Former Director, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance,

Government of India. Personal interview, 5 September.

Tallman, S. (2009) Global Strategy. UK: John Wiley.

34

Tipton, F. B. (2008) ‘Thumbs-up is a rude gesture in Australia: The presentation of culture in

international business textbooks’, Critical perspectives in international business 4(1): 7-24.

Wall Street Journal (1977) ‘Coke is right’, August 10: A14.

Wall Street Journal, 1977. Coke is right. August 10: A14.

Westwood, R., and Jack, G. (2007) ‘Manifesto for a postcolonial international business and management

studies’, Critical Perspectives on International Business 3(3): 246-265.

Wild, J. J., Wild, K. L., and Han, J. C. Y. (2010) International Business 5ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Pearson.

35

Table 1: Select Portrayals of Coca-Cola’s Exit in IB Textbooks

No.

Book

Chapter/ Major

Section

Section/

Paragraph

Context

Quote

1.

Czinkota,

et al., 7ed.,

2005, p.

95.

Trade &

Investment

Policies

Managing the

Policy

Relationship

Host countries, on the other hand, try to enhance their role by instituting control

policies and performance requirements. …In some cases, demands of this type

have led to firms’ packing their bags. For example, Coca-Cola left India when

the government demanded access to what the firm considered to be confidential

intellectual property.

2.

Deresky

2006,

p.318

(Case

written by

ICFAI)

Case: ‘Pepsi's

entry into

India’

Letter to Pepsi

“In the regulatory environment of the late 1970s, foreign enterprises operating

in any non-priority sector in India could not own more than a 40% stake in the

ventures. Coca-Cola ran its operations through a 100% subsidiary. After the

company refused to partner with an Indian company and share its technology, it

had to stop its operations and leave the country.”

3.

Griffin &

Pustay,

2007, p.43

Global

India/ Profile

marketplaces

and business

centers/ The

marketplaces of

Asia

“Until 1991, India discouraged foreign investment, limiting foreign owners to

minority positions in Indian enterprises and imposing other onerous

requirements. For example, as a condition for remaining in the country, the

Coca-Cola company was retroactively required in the 1970s to divulge its secret

soft drink formula. Coca-Cola refused and chose to leave the market.”

4.

Hill, 7ed.,

2011a,

National

differences in

“When legal risks in a country are high, an international business may hesitate

entering into a long-term contract or joint-venture agreement with a firm in that

Focus on

managerial

36

p.84

political

economy

implications /

Risks

country. For example, in the 1970s when the Indian government passed a law

requiring all foreign investors to enter into joint ventures with Indian

companies, US companies such as IBM and Coca-Cola closed their investments

in India. They believed that the Indian legal system did not provide for adequate

protection of intellectual property rights, creating the very real danger that their

Indian partners might expropriate the intellectual property of the American

companies - which for IBM and Coca-Cola amounted to the core of their

competitive advantage.”

5.

Hill, 8ed.,

2011b,

p.79

National

differences in

political

economy/

Focus on

managerial

implications

Implications for

managers/ Risks

[Text same as Hill (2011a: 84); see above]

6.

Hodgetts,

et al., 2006,

p. 32.

Globalization

& Worldwide

Developments

India

In the mid 1970s, the country changed its rules and required that foreign

partners hold no more than 40 percent ownership in any business. As a result,

some MNCs left India.

7.

Holt &

Wigginton

2002, p.75

Government

relations and

political

risk/Profile

Douglas Daft,

CEO/

Experience of

crises

“Goizuetta and Coca-Cola also experienced more than a few crises. Early on,

India attempted to gain access to Coke's highly guarded formula for its syrup. In

what was called a blatant form of political blackmail, Indian officials and

investors wanted trade secrets in return for Coca-Cola's licensing rights to bottle

and market in India.”

“Goizuetta stood his ground, and Coke withdrew from India until agreements

could be reached without corruption or political avarice.”

8.

Peng,

2009,

Entering

foreign

Regulatory

risks/

“The government's tactics include removing incentives, demanding a higher

share of profits and taxes, and even confiscating foreign assets - in other words,

37

p.161

markets/

Institution

based

considerations

Expropriation

expropriation. The Indian government in the 1970s, for example, demanded that

Coca-Cola share its secret formula, something that the MNE did not even share

with the US government. At this time, the MNE had already invested substantial

sums of resources (called sunk costs) and often has to accommodate some new

demands; otherwise it may face expropriation or exit at a huge loss (as CocaCola did in India)…. Coca-Cola, for example, agreed to return to India in the

1990s with an explicit commitment from the government that its secret formula

would be untouchable.”

9.

Peng, 2ed.,

2011, p.

14/15.

Globalizing

Business

An Institution

Based View

Prior to 1991, India’s rules severely discriminated against foreign firms. As a

result, few foreign firms bothered to show up, and the few that did had a hard

time. For example, in 1the 1970s, the Indian government demanded that Coca

Cola either hand over the recipe for its secret syrup, which it does not even

share with the US government, or get out of India. Painfully, Coca Cola chose

to leave. Its return to India since the 1990s speaks volumes about how much the

rules of the game have changed in India.

10.

Punnett &

Ricks,

1997,

p.188

The political

environment of

international

business/

Integrative

approaches to

political risk

management

Choosing the

right

combination/

Protection of

firm specific

advantages

“Coca-Cola considers it 'secret formula' for producing the special taste of Coke

a key component to its success and protects this secret. The company has been

willing to forgo foreign investments in countries such as India because the

investment would put the secret formula at risk. The potential of profitable

operations was not enough of a benefit to offset the risk associated with loss of

such an important firm- specific advantage.”

11.