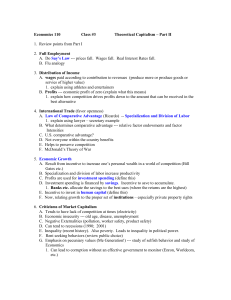

Lecture 2 – ECMC54

advertisement

Lecture 2 – ECMC54 Why Do Families Exist? Why do families exist = why do individuals bond together in more or less permanent groupings and share tasks such as: - Having, raising and supporting children - purchase, production and consumption of meals and necessities of life (i.e., sharing incomes and housework) - mutual care, affection, love and recreation Something like the question “Why do firms exist?” See Chapter 3 - neoclassical model of specialization and exchange - other economic reasons - why (too much) specialization may be disadvantageous to women - transaction cost, bargaining, other models of family - what we know about changes in the household division of labour Neoclassical (Becker) model Families have a productivity advantage. Family members join and make division of labour decisions to maximize utility of family members. Two types of work: market work and home work. Both are necessary to produce commodities. Individuals may have different abilities, comparative advantage in one type of production over another. Like theories of international trade. Specialization according to comparative advantage and trade with other country (family member) maximizes output. Obvious case – Where each family member has absolute advantage in one type of production John produces $10 of value each hour in market work; produces $5 of value in each hour of home work Jane produces $5 of value each hour of market work; produces $10 of value in each hour of home work. If John and Jane remain separate, and each has 8 hours of time per day, John might decide to do 6 hours market work and 2 hours home work for total output of 6x$10 + 2 x $5 = $70. Jane might do 7 hours of market work and 1 hour of home work to 7x$5 + 1x$10 = $45. If John and Jane co-operate, specialize and consume together, John could specialize 100% in market work (giving 8 x $10 = $80) and Jane could do 3 hours of home work and 5 hours of market work (giving 3 x $10 + 5 x $5 = $55). Total output has risen from $115 to $135. And market income has risen from $95 to $105, while the value of home work has risen from $20 to $30. Less obvious case – each has comparative advantage. Dave produces $10 of value each hour in market work; produces $5 of value in each hour of home work Diane produces $15 of value each hour of market work; produces $15 of value in each hour of home work. Diane’s OC of $1 home work = $1 market. Dave’s OC of $1 home work = $2 market. Comparative advantage = lower OC. If Dave and Diane remain separate, and each has 8 hours of time per day, Dave might decide to do 6 hours market work and 2 hours home work for total output of 6x$10 + 2 x $5 = $70. Diane might do 7 hours of market work and 1 hour of home work to 7x$15 + 1x$15 = $120. If Dave and Diane co-operate, specialize and consume together, Dave could specialize 100% in market work (giving 8 x $10 = $80) and Diane could do 2 hours of home work and 6 hours of market work (giving 2 x $15 + 6 x $15 = $120). Total output has risen from $190 to $200. The value of market income has risen from $165 to $170 while the value of home work has risen from $25 to $30. The example illustrates potential productivity gains due to specialization and exchange within a family. From Appendix M2 M1 $80 M1 = 80 – (8/3)H1 $50 $30 Jim H1 M2 = 50 – (5/9)H2 $90 H2 Kathy For Jim, dM/dH = -8/3: OC(H) = 8/3 dH/dM = -3/8: OC(M) = 3/8 For Kathy, dM/dH = -5/9; OC(H) = 5/9 dH/dM = -9/5; OC(M) = 9/5 Kathy has the comparative advantage in home work Jim has the comparative advantage in market work Combine the PPF’s (assumes she does first home work; he does first unit of market work, etc.) M M = 130 – (5/9)H, for 0<=H<=90, and M = 80 – (8/3)(H-90), for 90<=H<=120 $130 $80 $90 Combined $120 H Put the combined PPF on a per capita basis (representing output per person if equally shared) and we can see incentives to combine efforts M $80 $65 $50 $40 $30 $45 $60 Individual PPF’s and per capita combined $90 H This illustrates (again) potential gains from trade. Look also at preferences to begin to get a sense of decisions about division of labour. What difference do different shaped utility functions make? M M = 130 – (5/9)H, for 0<=H<=90, and M = 80 – (8/3)(H-90), for 90<=H<=120 $130 $80 $90 Combined $120 H M $130 $80 $90 Combined $120 H M $130 $80 $90 Combined $120 H Different shaped indifference curves will affect division of labour, but so will different productivities of two partners. But as long as comparative advantages differ, some degree of specialization will be efficient. What’s wrong (unrealistic) with this model? 1. constant productivities of home work and market work 2. only two types of work – no sub types 3. increased productivity implies formation of family (e.g., marriage) 4. productivity appears immutable, natural 5. single utility function for the family 6. no long term considerations – risk, accumulation of human capital, changes through life cycle. 7. ignores effects on bargaining power, dangers of specialization What’s useful? - rational basis for division of labour - trends in divorce, marriage, labour force participation could be explained by changing comparative advantages and/or changing preferences Other economic advantages to family formation 1. Economies of scale in household operation 2. Public goods 3. Externalities in consumption 4. Marriage-specific investments 5. Risk-pooling 6. Institutional advantages/Discrimination against other family types Transaction Cost and Bargaining Model - family does not operate by consensus - transaction costs are minimized by long term arrangements. Marriage creates rights and responsibilities and rules for dissolution. Contract that encourages marriage-specific investments, with some protection. - Bargaining power of each spouse is determined by “threat-point” (alternative level of wellbeing/income). Affected by wealth, abilities, wage rate, children, family law, probability of remarriage, eligibility for benefits/welfare. All these affect bargaining power over joint decisions. - income/benefits to different family members may change expenditure patterns/behaviours. The facts on non-market work and the household division of labour In the U.S. - amount of housework has declined over time for women (1978-2000 down 5 hrs/wk for nonmarried, 11 hrs/wk for married, while men up 1 hour/wk) - unequal division of market work/home work for married partners (in 2000, she 28/18, he 43/7, but she 34/16 if employed) - women have increased market work considerably (20 hrs/wk in 1978 to 29 hrs/wk in 2000) while men declined slightly. In Canada