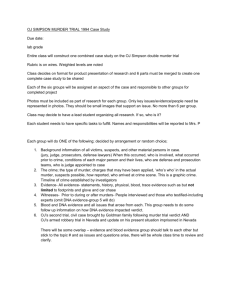

Criminal Law Outline

advertisement