City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

29-Jul-2013

Urban Heat Island Report:

City of Greater Geelong and

Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report

Client: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

ABN: 38 393 903 860

Prepared by

AECOM Australia Pty Ltd

Level 9, 8 Exhibition Street, Melbourne VIC 3000, Australia

T +61 3 9653 1234 F +61 3 9654 7117 www.aecom.com

ABN 20 093 846 925

In association with

Monash University

Job No.: 60299326

AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to the latest version of ISO9001 and ISO14001.

© AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM). All rights reserved.

AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other

party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any

third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and

AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional

principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which

may not have been verified. Subject to the above conditions, this document may be transmitted, reproduced or disseminated only in its entirety.

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Quality Information

Document

Urban Heat Island Report

Ref

60299326

Date

29-Jul-2013

Prepared by

Peter Steele

Reviewed by

Ben Smith

Revision History

Authorised

Revision

Date

Details

Revision 1

27-Jun-2013

Draft for review

Revision 2

29-Jul-2013

Final

Revision

Name/Position

Ben Smith

Team Leader –

Sustainability and

Climate Change

Ben Smith

Team Leader Sustainability and

Climate Change

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

Signature

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Table of Contents

Urban Heat Island Report

Executive Summary

1.0

Project context

2.0

What is the urban heat island (UHI)?

2.1

Urban heat island or urban heat?

2.2

Surface temperature versus air temperature

3.0

Urban heat risks

3.1

Overview of urban heat risks

3.2

Heat effects

3.2.1

City of Greater Geelong

3.2.2

City of Wyndham

3.3

Activities

3.3.1

City of Greater Geelong

3.3.2

Wyndham City Council

3.4

Vulnerability

3.4.1

City of Greater Geelong

3.4.2

City of Wyndham

3.5

Potential impact from climate change

3.5.1

City of Greater Geelong (Corangamite Region)

3.5.2

Wyndham City Council (Port Phillip and Westernport Region)

3.5.3

Potential impact of climate change on urban heat

4.0

Responding to UHI risks

4.1

Practical mitigation responses

4.2

Plan making

4.2.1

City of Greater Geelong

4.2.2

City of Wyndham

4.3

Operations / implementation

4.3.1

City of Greater Geelong

4.3.2

City of Wyndham

5.0

Limitations and next steps

5.1.1

Limitations

5.1.2

Further work

6.0

References

Appendix A

Appendix B

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

2

5

6

6

6

6

8

8

9

9

14

18

18

20

23

23

24

24

25

25

25

27

27

27

27

28

30

30

31

33

33

34

36

37

41

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

5

Executive Summary

The Urban Heat Island effect (UHI), and urban heat more broadly, has a range of potential impacts on health,

infrastructure and resource consumption. This report, commissioned by the City of Greater Geelong (CoGG) and

Wyndham City Council (WCC), explores the characteristics of urban heat for these two municipalities, utilising

data collected using airborne thermal sensing equipment.

The literature review undertaken for the project found a diverse range of academic research, government-oriented

discussion papers and toolkits focused on urban heat. It highlighted that urban heat can present a range of social,

economic and environmental risks and is likely to be further exacerbated by projected climate change. Relevant

literature also provided analysis of the various mitigation measures that may be used to reduce the extent and

impact of urban heat.

Context is critical in considering urban heat and possible mitigation strategies. Our analysis of vulnerability to

urban heat in the CoGG and WCC municipalities examined current and future urban form, delivery of core Council

services, and the impact of policies and strategies. Broad scale analysis using the available thermal sensor data

showed that both municipalities are affected by urban heat. Areas where a higher proportion of surfaces are

covered by built form showed higher surface temperatures, and the impact of green spaces, irrigated grass and

lighter coloured materials was also evident through lower surface temperature readings. The report also highlights

the potential for urban heat to impact on a broad range of Council facilities and services, and that vulnerable

segments of the community, including the elderly and disabled, may experience more severe impacts.

To derive the greatest value from the innovative thermal data available to CoGG and WCC, and to better respond

to urban heat risks, a range of potential responses have been identified for each municipality. The responses are

necessarily high level, and will rely on further work and consideration by CoGG and WCC and consultation with

relevant external stakeholders. Importantly, however, the responses recognise the importance of urban heat risks

being considered across Council, and not being seen as an issue restricted to the Environment or Sustainability

areas of local government.

The priority actions for CoGG and WCC identified through this process include:

-

Plan making: identify short term opportunities for urban heat risks to be considered in new plans related to

urban development, risk, health and wellbeing, capital works, and parks and open space.

-

Practical guidance: develop practical guidance for Council capital works and external developers, to inform

urban design, landscaping and built form decision-making.

-

Lead by example: explore opportunities for a practical retrofit pilot to be undertaken on a Council-owned

facility, utilising a combination of built form and landscaping approaches to demonstrate the potential for

local urban heat impacts to be reduced.

-

Improve data: consider the initiation of a structured monitoring program, using more readily and cheaply

available LANDSAT data, to further explore the characteristics of urban heat for each municipality and

inform mitigation efforts.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

1.0

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

6

Project context

City of Greater Geelong (CoGG) and Wyndham City Council (WCC) have jointly commissioned AECOM and

Monash University to provide this executive report to assist in communicating the risks from urban heat island,

and to set out the responses that are available in each of the local government areas (LGA’s) to mitigate these

risks.

The report is informed by a brief literature review, a review of climate change projections for Victoria and analysis

of airborne thermal remote sensing that was undertaken independently for WCC and CoGG on 24 January 2012

and 6 February 2013 respectively. See Appendix B for an overview of the thermal data collected.

The next steps for both councils in responding to this risk will be different. Given this, the report is structured to

provide both councils with content that is specifically relevant for their LGA, and which can be used to inform

further engagement, future work and strategy development.

2.0

What is the urban heat island (UHI)?

Urban development replaces natural surfaces and vegetation with the dry, hard surfaces and structures of roads,

footpaths and buildings. On sunny days, these surfaces accumulate and store solar heat energy. They are also

impervious meaning that when it rains the water drains away rapidly leaving little moisture in the ground layer and

consequently reducing evapotranspirative cooling. In addition to this, the height and form of high-density

development can trap heat at night. The combination of these factors, as well as other sources of heat in the

urban environment such as air conditioners and vehicle engines, often leads to warmer air temperatures in urban

areas than in the surrounding rural areas. This is particularly noticeable at night, when heat that is stored in the

urban landscape is slowly released, increasing the temperature differential between urban and rural areas. This is

referred to as the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI), which is generally considered the measure of this difference in

air temperatures between urban and rural areas. Local and international studies have found that the UHI effect

can add between 1°C to 6°C to ambient air temperature and is likely to be further exacerbated by climate change.

2.1

Urban heat island or urban heat?

There is an important distinction to be noted between UHI and a broader concept of urban heat. UHI refers

specifically to the difference between urban and rural temperatures, and is also often focused on night time

temperature differences. Urban heat, however, is a broader concept referring to the heat impacts associated with

urban environments. For the purposes of this study, UHI is less relevant than the identification, impact and

response to urban heat. As a result, the focus of the report will not be on the difference between rural and urban

temperatures, but the impact of, and response to, urban heat more broadly.

2.2

Surface temperature versus air temperature

Discussion of urban heat can be usefully separated into air temperature and surface temperature. Air temperature

urban heat is more commonly discussed, often in the context of urban areas having a higher air temperature at

night when compared surrounding rural areas. Air temperature can be impacted by a range of factors, for example

prevailing winds, proximity to the ocean and local meteorological conditions. Surface urban heat is a key

contributor to air temperature, and can be addressed through a range of mitigation measures. Importantly for this

study, the thermal imagery that is being analysed represents surface temperature as opposed to air temperature.

As a result, any discussion of future impacts and possible mitigation strategies is related primarily to surface

temperature. It should be noted that projections for temperature changes relating to climate change are based on

air temperature.

Figure 1 on the next page highlights this distinction as well as additional delineations that can be made in

assessing urban heat.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

7

Figure 1: Surface and air temperatures vary over different land use areas. Surface temperatures vary more than air temperatures during

the day, but they both are fairly similar at night. The dip and spike in surface temperatures over the pond show how water maintains a

fairly constant temperature day and night, due to its high heat capacity (US EPA, http://www.epa.gov/heatisland/about/index.htm)

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

3.0

Urban heat risks

3.1

Overview of urban heat risks

8

Where and to what extent urban heat occurs is the result of a wide variety of interacting factors. These include

building density, height, surface permeability, presence or absence of plants and trees, surface materials, surface

colours and meteorological conditions. Localised impacts, particularly related to surface urban heat, are

influenced by the specific characteristics of the surrounding urban environment.

Potential impacts associated with urban heat include:

-heat stress, leading to illness and mortality for humans and animals

-increased water use (irrigation, evaporative air conditioning)

-increased energy consumption (for air-conditioning or increased use of motorised transport)

-infrastructure failure (transport, electricity distribution).

Generally speaking, the risks are greatest when high activity areas with vulnerable populations are subject to

extreme heat, as depicted in Figure 2 below.

C

Exposure of the

population

Heat

B

Vulnerability A

B

Activity

B

A = Highest priority

C

C

B = Medium priority

C = Moderate priority

Figure 2: Diagram representing factors required to identify areas of high (A), medium (B) and moderate (C) priority for UGI

implementation for surface temperature heat mitigation. The key factors are daytime surface temperatures (Heat) and areas of high

activity (Activity), which combined indicate areas of high exposure. In addition, areas with high concentrations of vulnerable population

groups (Vulnerability) should be identified (Norton et al 2013).

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

3.2

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

9

Heat effects

The Western Melbourne region, which includes Wyndham City Council and City of Greater Geelong, has a

diverse range of urban environments. These include large, low-density, single use residential growth areas,

established residential suburbs, dense mixed use and commercial areas, and industrial precincts. The urban heat

risks to each of these urban environments are different and locally specific, and influenced by a range of factors.

Figure 3: Land surface temperatures observed from MODIS satellite imagery on 28-29 Jan 2009 for daytime (left) and night time (right)

(Loughnan et al. 2010)

Thermal imagery has been reviewed for this study. A number of specific heat effects and suggested approaches

for mitigation, based on the thermal imagery are set out in the sections below. The thermal flyover for Geelong

was undertaken on 6 February 2013 and for Wyndham on 24 January 2012. Limitations in respect of the thermal

data are set out in 5.1.1 however the imagery provides a good way to better understand a range of risks and to

begin to consider appropriate responses.

3.2.1

Table 1

City of Greater Geelong

Urban heat risks and potential responses based on thermal imagery data collected on 6 February 2013

Street scene

A comparison of two streets is presented below, one with trees (northern east-west street) and one without

(southern east-west street). The cooling nature of the street trees is evident.

However, these street are designed for different purposes: the open street is for traffic, while the street with

trees is designed for parking and pedestrians.

Location: 118-136 Little Malop St, Geelong

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

10

Car parks

Unshaded car parks show high surface temperatures. Planting trees within the car park would be beneficial.

This car park is close to the ocean, and there is likely to be sea breezes providing cooling effects despite the

high surface temperatures. However, trees provide shading as well, which is important for improving human

thermal comfort.

Location: Deakin University car park 68-92 Cavendish St, Geelong

Hot spots and mapping anomalies

Data can be used to identify hotspots surrounding areas with populations that are vulnerable to heat such as

schools. The asphalt car park is a hot-spot, as is the unirrigated grass area. The effect of irrigation can be

seen in the area to the east of the shade sails.

The very cold (blue) roof is an artefact of the data collection process and is due to the low emissivity.

The surrounding wide roads could also be targeted for vegetation to reduce surface heating.

Location: 275 Moorabool St, Geelong

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

11

The block below is particularly devoid of vegetation and has a very high level of imperviousness, and shows

very high ground level surface temperatures. This would be classed as a ‘hot-spot’.

Location: 31 Little Ryrie St, Geelong

Public open space

Public open space can be irrigated to provide a more thermally comfortable environment. The surface here

(dark tan bark) actually serves to increase the surface temperature and surfaces are as hot as the

surrounding asphalt roads. This park does provide tree shade however, which is beneficial for human

thermal comfort.

Location:160-166 McKillop St, Geelong

Some of the hottest areas during the day are wide open streets where there is little shading from buildings or

vegetation.

High amounts of solar radiation reach the surface here, resulting in intense heating.

Vegetation is most effective during the day in wide open streets where solar access is high.

Location: 16 Sydney Ave, Geelong

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

12

Soil moisture

The role of soil moisture can also be seen in this image. Along the river, and the depression on the west of

the image, grass surface temperatures are lower as moisture drains to these areas.

Location: La Trobe Terrace, Belmont

Building shade

The colour palette has been changed in this image to emphasise the effects of building shade on surface

temperatures. Surface temperatures were some 25 degrees cooler when shaded. Of course, this shade will

move throughout the day, but in designing streets for pedestrians and public space, solar access should be

considered.

Shading patterns in the thermal image are slightly different form the aerial image because of the different

times of the day.

Location: 4 Corio St, Geelong

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

13

Tree shade

Again to emphasise the cooling effect the colour palette was changed. In the image below the tree canopy

temperature is lower than surrounding urban materials because trees absorb and reflect solar energy, and

also transpire. Plus, the shading effect of this large canopy tree can be seen. Large shade trees should be

protected and promoted.

Again, shade patterns will change throughout the day, so designing spaces should consider solar access

and strategically place trees

Location: 283 Ryrie St, Geelong

In another example to emphasis tree effects: the tree canopy temperatures in the irrigated park appear

cooler than in the adjacent park to the south-east. This could possibly be due to the different amounts of

irrigation in the parks (it could also be a result of different tree species)

Irrigation provides more moisture to the root zone for trees to draw on for photosynthesis and transpiration.

Tree canopy temperatures did vary and this can also be a result of the micro-climate these trees are

exposed to. Trees surrounded by urban surfaces must endure higher surface temperatures (from the ground

and walls) and warmer, drier conditions. Providing soil moisture can help trees endure urban conditions.

Location: 6 Bellerine St

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

3.2.2

Table 2

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

14

City of Wyndham

Urban heat risks and potential responses based on thermal imagery data collected on 24 January 2012

Hot spots and mapping anomalies

Some rooftops appear very cold such shopping complexes and some industrial areas. These surface

temperatures are very difficult to interpret. While the light colour of the roof will reflect more solar radiation,

these cold roofs are also an artefact of the data collection approach. Remote sensing does not account for

the emissivity of the surface (emissivity is the ability of a surface to emit radiation). Materials like corrugated

iron have low emissivity, and hence appear cold. It is very difficult to account for emissivity and these

rooftops should be excluded from analysis. These roofs could be underestimated by anywhere between 20

and 40°C.

Despite the apparent cool temperatures, this is a priority area because of high pedestrian activity. The

buildings will provide some shading during the day, but more vegetation and water availability could improve

the micro-climate here during the day.

Location: 4 Main St, Point Cook

Very dry, barren areas show surface temperatures that are high during the day, and a similar temperature to

urban surfaces.

One difference, however, is that these barren surfaces will actually cool rapidly at night, while the urban

surfaces will remain warm.

Dry, barren surfaces will hinder daytime thermal comfort. Vegetation and irrigation can mitigate this.

Location: Boardwalk Boulevard, Point Cook

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

15

The light coloured roof in the image below is around 6°C cooler than surrounding rooftops. The high

reflectivity of the roof would contribute to reduced atmospheric heating. It would also be likely to have

building energy efficiency benefits. Products are available in the market such as ThermoShield which

provide highly reflective ceramic paints that are designed to reflect across the entire shortwave spectrum.

Paints are available in other colours, and represent a relatively inexpensive mitigation action with potential

for widespread uptake.

Location: 27 Peppertree Dr, Point Cook

Soil moisture

The effects of irrigation can be clearly seen. This irrigated oval (~32°) is around 12-13°C cooler than

surrounding unirrigated ground cover (~45°C).

Increasing soil moisture reduces surface temperatures during the day. It can slow surface cooling marginally

at night, meaning these surfaces will still be cooler than urban surfaces. The overall effect of irrigation on

surface temperature is a net benefit.

Location: 19 Kingsley Ave, Point Cook

In contrast with the irrigated oval, at Emmanuel College (above), these are synthetic turf basketball courts

which show temperatures of 48-49°C. This space is designed for school children physical activity and would

deliver a warmer and higher radiative environment than irrigated sports-fields.

Location: 2-40 Foxwood Dr, Point Cook (overleaf)

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

16

Evapo-transpiration cooling

The tops of these trees are much cooler during the day. They provide shading and transpirational cooling.

As this image was taken at solar noon, shading effects of trees on surrounding surfaces can’t be seen.

Location: 17 Wattle Grove, Point Cook

Public open space

Public space. In the hottest area of this public space is a playground. Public space should be designed to

minimise exposure to extreme heat. Irrigated vegetation can provide a more comfortable thermal environment, as

well as improve amenity.

Location: 20 Sidney Nolan Walk, Point Cook

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

17

Water bodies

Obviously, water bodies are much cooler during the day due to evaporation of water and a high thermal mass.

This higher thermal mass means that at night, surface temperatures can be relatively warm, but surfaces may still

be evaporating so providing cooling. Night time surface temperatures of water will still be cooler than urban

surfaces on hot nights. Strategically placed water bodies, or water sensitive urban design measures that retain

water in the landscape, can be used to provide local cooling.

Location: 64 Scrubwren Dr, Williams Landing

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

3.3

Activities

3.3.1

City of Greater Geelong

18

Council facilities and services

CoGG owns approximately 700 facilities across the municipality, varying from significant office buildings to parks

to toilet blocks. A selection of CoGG facilities is shown in Figure 4 on the next page. When compared with the

thermal data, shown in Appendix B, it can be seen that Council facilities are located in a range of urban

environments and are likely to experience varying degrees of urban heat. While more detailed analysis is required

to determine the relationship between CoGG facilities and localised urban heat, the analysis in Section 3.2

highlights the potential impact of a range of urban environments including streets, buildings, ovals and

playgrounds.

In addition to owning and managing physical assets, Council employees deliver a range of services that include

community support and outreach, management of recreation facilities, waste management and administration of

local laws.

Urban heat poses a range of potential risks to CoGG that relate to both physical assets and service delivery. In

addition, Council’s assets also have the potential to increase urban heat impacts. Potential risks include:

-

heat stress to Council employees required to work outdoors (e.g. maintenance staff at recreation facilities,

community outreach workers)

-

increased operating costs for Council buildings due to increased electricity consumption for air conditioning

-

reduced amenity of Council-owned recreation facilities, such as playgrounds

-

increased demand for community support for vulnerable residents during periods of extreme heat

(exacerbated by urban heat impacts).

New urban development

The population of CoGG is growing and to support this growth significant additional urban development will

continue to occur. The number of private dwellings in the municipality is predicted to increase from approximately

101,000 in 2013 to 134,000 in 2031 (Forecast.id 2011b), and the majority of this increase will occur in growth

areas such as Armstrong Creek. In many cases this growth will result in vegetated, non-urban environments being

replaced by the hard surfaces and materials that are associated with urban heat impacts. Figure 4 on the

following page shows the arrangement of existing land uses across the municipality, and highlights the Armstrong

Creek growth area.

CoGG has the capacity to influence the location and type of development that occurs through strategic and

statutory planning tools. While there are limits to the requirements that Council can make of developers, there are

a range of potential urban heat mitigation measures that can be pursued through this process to reduce the

likelihood and impact of urban heat on future development.

Potential urban heat risks posed to new urban growth include:

-

health and wellbeing impact on future residents, particularly vulnerable groups (e.g. elderly, disabled)

-

increase in living expenses due to increased reliance on air conditioning and private vehicle transport

-

increase in social isolation

-

increase in urban heat impacts on surrounding areas.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Figure 4 CoGG land uses, key growth area and selected Council facilities (ABS data composite including planning zones)

1 - Ocean Grove Library & Shopfront

2 - Geelong West Town Hall

3 - Bellarine Multi Arts Centre

4 - Bellarine Aquatic Sports Centre

5 - City Hall

6 - Civic Centre Car Park

7 - Queens Park Golf Club & Kiosk

8 - Corio Leisure Time Centre

9 - City works (Corio)

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

19

AECOM

3.3.2

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

20

Wyndham City Council

Council facilities and services

WCC owns approximately 800 facilities across the municipality, varying from significant office buildings to parks to

small buildings such as toilet blocks. Around 150 of these facilities are buildings, and the municipality is also

responsible for 40 significant parts and sporting reserves. In addition to owning and managing physical assets,

Council employees deliver a range of services that include community support and outreach, management of

recreation facilities, waste management and administration of local laws.

Urban heat poses a range of potential risks to WCC that relate to both physical assets and service delivery. In

addition to being impacted by urban heat, Council’s assets also have the potential to increase urban heat impacts.

Potential risks include:

-

heat stress to Council employees required to work outdoors (e.g. maintenance staff at recreation facilities,

community outreach workers)

-

increased operating costs for Council buildings due to increased electricity consumption for air conditioning

-

reduced amenity of Council-owned recreation facilities, such as playgrounds

-

increased demand for community support for vulnerable residents during periods of extreme heat

(exacerbated by urban heat impacts).

New urban development

WCC is one of Victoria’s fastest growing local government areas, and to support this rapid growth significant

additional urban development will continue to occur. The number of private dwellings in the municipality is

predicted to increase from approximately 70,000 in 2013 to 124,000 in 2031 (Forecast.id 2011a), and the majority

of this increase will occur in new growth areas such as Ballan Road and Westbrook. In many cases this growth

will result in vegetated, non-urban environments being replaced by the hard surfaces and materials that are

associated with urban heat impacts. Figure 5 on the following page identifies a number of significant growth areas

in the municipality. These are areas where urban heat risks may increase as development occurs, however also

represent opportunities to implement urban heat mitigation strategies.

WCC has the capacity to influence the location and type of development that occurs through strategic and

statutory planning tools. While there are limits to the requirements that Council can make of developers, there are

a range of potential urban heat mitigation measures that can be pursued through this process to reduce the

likelihood and impact of urban heat on future development. These are explored in Section 4.0 of this report.

Potential urban heat risks posed to new urban growth include:

-

health and wellbeing impact on future residents, particularly vulnerable groups (e.g. elderly, disabled)

-

increase in living expenses due to increased reliance on air conditioning and private vehicle transport

-

increase in social isolation

-

increase in urban heat impacts on surrounding areas.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Figure 5 WCC land uses, key growth areas and selected Council facilities (ABS data composite including planning zones)

1 - Wyndham City Council

2 - Hoppers Crossing Youth Resource Centre

3 - Wyndham Leisure & Events Centre

4 - Wyndham Cultural Centre

5 - Point Cook Learning Centre

6 - Werribee South Caravan Park

7 - Chirnside Park

8 - Manor Lakes Community Learning Centre

9 - Saltwater Reserve

10 - Jamieson Way Community Centre

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

21

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

22

The effects of urban development on land surface temperature can be seen below in Figure 6. While it is

important to recognise the numerous variables that influence the individual temperature readings of these images,

the broad pattern of urban development over time, and the impact of this on surface temperature reading, is

instructive when considering the influence of built form on urban heat.

Figure 6 LANDSAT land surface temperature image (average of 7 images from 1999-2005: Nury et al. 2012) and right: LANDSAT image with Wyndham

thermal flyover overlaid (30m resolution) for 2012.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

3.4

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

23

Vulnerability

Research has identified the increased risk posed by urban heat to vulnerable populations, including the elderly

and those suffering chronic illness and disability (Loughnan et al 2013). Urban heat may also have a greater

impact on low income households due to the potential impact on living costs. The ABS provides an indicator of

socio-economic vulnerability called Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), which can be used to identify the

geographic spread of socio-economic vulnerability.

Urban heat can cause or exacerbate health impacts such as heat stress, resulting in illness or death, and can also

compound issues of social isolation by reducing comfort levels in outdoor areas and meeting places. It may also

result in increased living costs associated with air conditioning and transport. Resulting flow on effects can include

increased demand for medical care and emergency services, resulting in resource strains for local government,

hospitals and emergency services.

Thermal data has the potential to be used to identify whether urban heat risks are likely to disproportionally affect

vulnerable residents, and enable mitigation measures to be prioritised to these areas. Loughnan et al (2009)

developed a method to identify broad spatial patterns of vulnerability to heat stress at the local government area

level. This utilises a series of 5 indicators:

-

Large numbers of aged care facilities

-

Language other than English spoken at home

-

Elderly people living alone

-

Low density (suburban) areas

-

High proportion of very old or very young residents.

While broad scale analysis of this nature is useful in identifying general patterns of vulnerability, Norton et al

(2013) recognise the need for ‘finer grain’ analysis to enable specific, localised responses to be undertaken. A

recently launched online mapping project based on this report, ‘Mapping Vulnerability Index1’, undertakes this at

census collector district level for all Australian capital cities. This online resource, and the discussion found in the

VCCCAR supported report ‘Decision principles for the selection and placement of green infrastructure to mitigate

urban hotspots and heat waves’, could be utilised by CoGG and WCC to further explore the geographic spread of

vulnerability, intersection of this with urban heat ‘hot spots’ and prioritise mitigation efforts in these area.

The following sections introduce some of the broad indicators of vulnerability for CoGG and WCC. It was not

within the scope of this report to undertake detailed, localised analysis of the intersection between vulnerability

and urban heat impacts, however it is recommended that this is undertaken as CoGG and WCC plan and

prioritise specific urban heat responses.

3.4.1

City of Greater Geelong

The following indicators of vulnerability are taken from the CoGG Profile.id website (2013a).

Age

CoGG has an older population in comparison to Greater Melbourne. Residents in the older age range, such as 65

and over, are not distributed evenly throughout the municipality which may indicate areas with a higher proportion

of older residents are more vulnerable.

Disability

Approximately 5.6% of the CoGG population requires assistance with day-to-day tasks due to disability. This

population is not evenly distributed across the municipality, and a number of areas of high concentration of

disability assistance are evident.

Income and education

1

NCCARF, CRF for Water Sensitive Cities, Water for Liveability and Monash University (accessed 22.07.13),

http://www.mappingvulnerabilityindex.com/

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

24

CoGG has a SEIFA score of 993, placing it around the middle of the ranking of disadvantage across Victoria’s

municipalities. Within the municipality, the SEIFA index notes the highest level of disadvantage in the following

suburbs:

-

Norlane

-

Whittington

-

Corio

-

Thomson/Breakwater.

Specific analysis of thermal data for these areas was not undertaken through this project, however all are located

within parts of the municipality that experience urban heat effects. Further detailed analysis to understand the

intersection between the most vulnerable parts of the community and the most severe urban heat impacts would

enable localised mitigation to be prioritised.

3.4.2

City of Wyndham

The following indicators of vulnerability are taken from the WCC Profile.id website (2013b).

Age

WCC has a younger population in comparison to Greater Melbourne, potentially reducing vulnerability to the

health impacts of urban heat. Residents in the older age range, such as 65 and over, are not distributed evenly

throughout the municipality which may indicate areas with a higher proportion of older residents are more

vulnerable.

Disability

Approximately 3.4% of the WCC population requires assistance with day-to-day tasks due to disability. This

population is not evenly distributed across the municipality, and a number of areas of high concentration of

disability assistance are evident.

Income and education

WCC has a SEIFA score of 1,013, placing it around the middle of the ranking of disadvantage across Victoria’s

municipalities. Within the municipality, the SEIFA index notes the highest level of disadvantage in the following

suburbs:

-

Heathdale

-

Manorvale

-

Woodville

-

Mossfiel.

Specific analysis of thermal data for these areas was not undertaken through this project, however all are located

within parts of the municipality that experience urban heat effects. Further detailed analysis to understand the

intersection between the most vulnerable parts of the community and the most severe urban heat impacts would

enable localised mitigation to be prioritised.

3.5

Potential impact from climate change

Climate change projections prepared by CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) provide an indication of the

likely effect of future climate change on temperatures, rainfall, extreme weather events and sea level. These

projections are based on greenhouse gas emission models and scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report (2007). While the extent of projected changes will vary

between specific locations within the CoGG and WCC local government areas, the broad changes expected are

largely consistent. The detail of localised impacts are highly uncertain and beyond the scope of this project to

explore, and are also less relevant when considering urban heat impacts at a strategic level.

The primary climate changes that will impact on urban heat are changes to temperatures, both average

temperatures and number of extreme heat events, and changes in rainfall patterns. Key projected changes that

could influence future urban heat are summarised below (DSE 2008a):

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

3.5.1

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

25

City of Greater Geelong (Corangamite Region)

Temperature

-

Under a medium emissions scenario, annual average temperature is expected to be between 0.5 to 1.1ºC

warmer in 2030.

-

By 2070, average annual temperature are expected to be between 0.8 to 1.8ºC warmer under a lower

emissions scenario or between 1.6 to 3.5 ºC warmer under the high emissions scenario.

-

The number of days over 30ºC each year is expected to increase from 21 to 26 by 2030 and up to 40 by

2070.

-

The number of days over 35ºC each year is expected to increase from 4 to 6 by 2030 and up to 12 by 2070

under a high scenario.

Rainfall

-

While conditions are expected to be drier, when it does rain, rainfall intensity is expected to increase. Under

a high emissions scenario average annual rainfall could decrease by up to 12% by 2070.

3.5.2

Wyndham City Council (Port Phillip and Westernport Region)

Temperature

-

Under a medium emissions scenario, annual average air temperature is expected to be between 0.6 to

1.1ºC warmer in 2030.

-

By 2070, average annual air temperature are expected to be between 0.9 to 1.9ºC warmer under a lower

emissions scenario or between 1.8 to 3.7 ºC warmer under the high emissions scenario.

-

The number of days over 30ºC each year is expected to increase from 30 to 34 by 2030 and up to 49 by

2070.

-

The number of days over 35ºC each year is expected to increase from 9 to 11 by 2030 and up to 20 by 2070

under a high scenario.

-

The number of days over 40ºC each year could double by 2030 and increase to up to 5 days by 2070.

Rainfall

3.5.3

While conditions are expected to be drier, when it does rain, rainfall intensity is expected to increase. Under

a high emissions scenario average annual rainfall could decrease by up to 24% by 2070.

Potential impact of climate change on urban heat

Increases in temperature may increase the absorption and retention of heat by built surfaces. Changes to rainfall

patterns may reduce vegetation cover and reduce the moisture content of ground surfaces, which can result in

increased daytime surface heating. In a broad sense, it is likely that these projected changes will exacerbate the

extent and impacts of urban heat already being observed. Discussed in section 3.0 above, this could result in

impacts on health, infrastructure, essential service delivery and the economy.

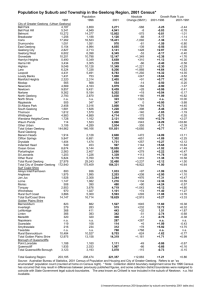

Table 3 Projected changes in number of extreme heat days in Melbourne (DSE 2008b)

2030 (medium

emissions)

Current

2070 (low

emissions)

2070 (high

emissions)

Annual days over

30C

30

34

39

49

Annual days over

35C

9

11

14

20

Annual days over

40C

1

2

3

5

The table above summarises the potential increase in days of extreme heat for the Melbourne region, a

particularly relevant indicator when considering urban heat impacts. It highlights the significant changes projected

under current climate change scenarios. An increase in the frequency of extreme heat days is likely to result in an

increase in hospital admissions, injuries and deaths due to heat stress, dehydration and sunburn, as well as

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

disruptions to transport and other essential infrastructure and services (DSE 2008b). If urban heat is not

managed, these impacts could be significantly exacerbated.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

26

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

4.0

Responding to UHI risks

4.1

Practical mitigation responses

27

A range of measures have been identified in the review of relevant literature that have potential to reduce urban

heat impacts. These are outlined in Table 4 below. The measures relevant to City of Greater Geelong and

Wyndham City Council will depend on the individual circumstances of the facility or urban area being considered,

as well as the objectives of the mitigation effort. All of these practical mitigation measures need to be considered

by councils in plan making and operations.

Table 4 General urban heat mitigation opportunities (adapted from Coutts et al 2010).

Mitigation measure

Desired effect

Increase vegetation

Encourage evapo-transpirative cooling, shade built surfaces.

Water sensitive urban design

Retain water to increase evaporation, increase water availability for

irrigation.

Increased albedo

Increase reflection of solar radiation, reducing heat storage.

High thermal emittance surfaces

(use of reflective coating for roof

surfaces, allowing traditional

colours to be maintained).

Reduce heat storage in roof coverings.

Outdoor landscaping

Protect buildings from solar radiation using external vegetation. Use of

deciduous species can allow protection in summer and access in winter.

Street design

Use street orientation and width to allow urban ventilation and balance

urban heat impacts with passive thermal performance.

Parkland and open space

Use vegetated open space to provide local cooling, including for

surrounding urban areas.

Green roofs / walls

Reduce heat transfer into buildings and encourage evapotranspiration.

Evaporative air coolers

Reduce the release of waste heat from reverse cycle air conditioning

outside buildings (increased water consumption is a drawback).

Building design

Improve occupant comfort and reduce cooling requirements.

Mass transport / active transport

Reduce private vehicle use, resulting in less waste heat from exhaust.

4.2

Plan making

The tables below highlight examples of council strategies and plans where there may be opportunities to make

specific mention of urban heat risks and mitigation approaches, or where there are opportunities to improve what

is already incorporated into existing plan documents. It should be noted that the examples included below

represent a small sample of the opportunities that may exist to better incorporate urban heat considerations into

Council plans and strategies, and a complete review of existing plans and strategies has not been completed as

part of this study.

4.2.1

City of Greater Geelong

Table 5 Key plans and strategies – City of Greater Geelong.

Plan

Current status and opportunity

Precinct Structure

Plans (PSP)

The Armstrong Creek East Precinct and Town Centre PSPs were reviewed to understand

current appreciation of urban heat in the context of future development. 26,207 of the

76,460 expected population growth to 2031 in CoGG is projected for the Armstrong

Creek Growth Area. Ensuring PSPs for this area adequately consider urban heat risks,

among other sustainability and liveability considerations, will make a significant impact.

The PSPs reviewed made no specific reference to urban heat, however a range of

provisions were identified that may support reduced urban heat impacts. These include

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Plan

28

Current status and opportunity

objectives, guidelines and requirements related to:

-

shading streets and pedestrian spaces through verandahs and shade trees

-

minimising areas of unshaded car park

-

urban form and landscaping to provide shade around buildings.

Future PSPs represent an important opportunity to consider how street design and

orientation, water management and landscaping can support improved urban heat

outcomes. High level strategic objectives, supported by more detailed provisions in

design guidelines and infrastructure plans, could be altered to include consideration of

urban heat.

PSP Guidelines include a requirement for an energy statement. Urban heat is a

consideration that should form part of this statement, given its potential to increase

energy consumption

2009-2013 Geelong

Health and Wellbeing

Plan

The current Geelong Health and Wellbeing Plan expires this year. This represents an

important opportunity to bring the consideration of urban heat into the municipality’s

strategic plan for community health and wellbeing. The current plan recognises the

impact that urban design and open space networks can have on health and wellbeing,

however does not recognise the potential risks of urban heat in this context.

The revised plan could recognise the impact urban heat can have on physical and mental

health, and recommend consideration of urban heat impacts in the context of service

delivery, emergency management planning, new urban development and Council

facilities. In particular, the plan could identify risks to vulnerable segments of the

community, and put in place strategies to manage these risks.

City of Greater

Geelong Heatwave

Management Plan

The CoGG Heatwave Management Plan, developed in October 2009, sets out the

systems and processes Council intends to put in place to reduce the impact of heatwaves

on public health. The plan makes note of the factors contributing to health impacts of

heatwaves, however makes no specific mention of the potential for heatwaves impacts to

be exacerbated by urban heat. As has been outlined in this report, local temperatures

can be significantly influenced by the built form and landscaping associated with urban

environments. In the event of a heatwave, areas likely to experience higher temperatures

due to urban form could be more vulnerable to public health impacts.

A revised Heatwave Management Plan should recognise this elevated risk and include

procedures to respond. Subject to further work and analysis, a heatwave vulnerability

map could be developed that made note of both the most vulnerable populations as well

as the urban areas most likely to experience elevated temperatures.

4.2.2

City of Wyndham

Table 6 Key plans and strategies – City of Wyndham.

Plan

Current status and opportunity

Precinct Structure

Plans (PSP)

Existing PSPs for Ballan Road and Manor Lakes were reviewed, to understand current

recognition of urban heat impacts. While these plans make no specific reference to urban

heat, they do include a range of provisions that have potential to support improved urban

heat outcomes. These include objectives, guidelines and requirements related to:

-

encouraging canopy tree cover in streets, car parks and open spaces (e.g. Ballan

Road PSP and Manor Lakes PSP)

-

integration of open space networks (e.g. Ballan Road PSP)

-

using recycled water to contribute to maintaining a green urban environment (e.g.

Ballan Road PSP)

-

use of buildings and landscape treatments to provide shade (e.g. Manor Lakes).

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

Plan

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

29

Current status and opportunity

Future PSPs represent an important opportunity to consider how street design and

orientation, water management, landscaping, and material and colour selection can

support improved urban heat outcomes. High level strategic objectives, supported by

more detailed provisions in design guidelines and infrastructure plans, could be altered to

include consideration of urban heat.

PSP Guidelines include a requirement for an energy statement. Urban heat is a

consideration that should form part of this statement, given its potential to increase

energy consumption

Municipal Strategic

Statement (MSS)

The MSS sets the broad strategic direction for planning across the municipality. It is

currently under review, with a draft version out for comment. Key urban heat concepts

and actions relevant to strategic and statutory planning could be included in the final draft

of the MSS, providing a strategic basis for future planning decisions that consider urban

heat impacts.

Community Health

and Wellbeing Plan

The Community Health and Wellbeing Plan is due to expire at the end of 2013. The

revised version of this plan has the opportunity to consideration to urban heat impacts on

health and wellbeing. Vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and disabled, can be

disproportionally affected by extreme heat, and urban heat impacts have the potential to

exacerbate this.

Recreational behaviours and exercise can also be impacted. As shown by analysis of

surface temperature of public open spaces including ovals and play grounds design,

material selection and landscaping can significantly influence surface temperatures of

important public spaces.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

4.3

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

30

Operations / implementation

In addition to being considered at a strategic level in plan making, councils also need to consider urban heat in

their day to day operations, including maintenance and replacement activities (buildings and public open space),

provision of guidance and statutory decision-making (planning) and in considering public health and emergency

response policies and procedures.

The following tables provide an indication of the potential relevance of urban heat to each council directorate for

both CoGG and WCC. This is not intended to be exhaustive, but to provide an initial indication of the potential

risks or responses that each directorate may consider in relation to urban heat.

4.3.1

City of Greater Geelong

Table 7 Integrating urban heat into core function activities – City of Greater Geelong

Directorate

Core functions

Urban heat relevance

City services

Engineering

Environment and Natural Resources

Infrastructure Operations and Waste

Parks and support services

Consideration of urban heat in specification

and design of new infrastructure, maintenance

of existing infrastructure.

Community services

Aged and Disability Services

Arts and Culture

Community Development

Family Services

Health and Local Laws

Planning for urban heat impacts on vulnerable

groups, including elderly and disabled

members of the community.

Potential to reduce passive street surveillance

during extreme events and subsequently

increase crime rates and anti-social behaviour.

Corporate services

Communication and Marketing

Administration and Governance

Corporate Strategy and Property

Management

Customer Services and Councillor

Support

Financial Services

Information Services

Organisation Development

Produce property management guidance

outlining urban heat responses

City Development

Planning Strategy and Economic

Development

Tourism

Consider incorporating assessment of urban

heat risks in new subdivisions and planning

permit approvals processes.

Economic development,

planning and tourism

Incorporate into future climate change

adaptation work, including Barwon South West

regional plan.

Integrating urban heat mitigation into

upcoming strategies, budgets, staffing,

resourcing, link to updated risk register.

Consider and plan for potential increased

cooling costs due to a combination of climate

change and rising energy prices, compounded

by urban heat.

Consider inclusion of specific reference to

urban heat in future revisions of the Municipal

Strategic Statement (MSS), new overlays and

zone amendments.

Encourage developers to include urban heat

mitigation provisions in urban design

guidelines of new estates (e.g. roof colour and

landscaping).

Produce planning and design guidance for

new development, renewal projects and

renovations. This to consider various scales

including precinct/subdivision, block, street

and individual building.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

31

Directorate

Core functions

Urban heat relevance

Projects, recreation and

central Geelong

Capital Projects

Events, Central Geelong and

Waterfront

Leisure Services

Sport and Recreation

Strategic Projects/Urban Design

Consideration of urban heat in specification

and design of new Council facilities including

buildings, open spaces and sporting facilities.

4.3.2

Consider urban heat outcomes in street tree

selection and maintenance, landscaping and

maintenance of parks (including irrigation).

City of Wyndham

Table 8 Integrating urban heat into core function activities – City of Wyndham

Directorate

Core functions

Urban heat relevance

Sustainable

Development

Communications and Events

Town Planning

Environment and Sustainability

Economic Development

Strategic Planning

Consider urban heat in development of future

environment and climate change strategies,

including adaptation planning.

Consider inclusion of specific reference to

urban heat in future revisions of the Municipal

Strategic Statement (MSS), new overlays and

zone amendments.

Encourage developers to include urban heat

mitigation provisions in urban design

guidelines of new estates (e.g. roof colour and

landscaping).

Consider incorporating assessment of urban

heat risks in new subdivisions and planning

permit approvals processes.

Produce planning and design guidance for

new development, urban renewal projects and

smaller buildings. This to consider various

scales including precinct/subdivision, city

block, street and individual building.

Community

Development

Libraries and Community Learning

Aged, Disability and Recovery

Early Years and Youth

Social Development

Business Services

Advocacy

Corporate Services

Planning for urban heat impacts on vulnerable

groups, including elderly and disabled

members of the community.

Advocate for urban heat impacts to be

incorporated into State Planning Policy

Framework, to provide strategic support for

local responses.

Information Services

City Governance

Financial Services

Risk and Compliance

Organisational Development

Increased urban heat impacts have the

potential to reduce passive street surveillance

during extreme events and subsequently

increase crime rates and anti-social behaviour.

Produce property management guidance

outlining urban heat responses

Integrating urban heat mitigation into

upcoming strategies, budgets, staffing,

resourcing, link to updated risk register.

Infrastructure

City Presentation and Recreation

Buildings and Waste

Major Projects

Consideration of urban heat in specification

and design of new Council facilities including

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

Directorate

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

32

Core functions

Urban heat relevance

Engineering Services

Parks

Assets Management and

Maintenance

buildings, open spaces and sporting facilities.

Consider urban heat outcomes in street tree

selection and maintenance, landscaping and

maintenance of parks (including irrigation).

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

5.0

Limitations and next steps

5.1.1

Limitations

33

High resolution thermal mapping provides a great communication tool to convey the idea of urban heat. However,

there are some limitations with high resolution thermal imagery that are of concern.

Corrections: Thermal remote sensing actually involves the measurement of surface radiation, and using the

inverse of Plank’s Law, is converted to a surface ‘brightness’ temperature. Data supplied by the provider here is

essentially a raw data product that has only been radiometrically corrected. The data is not corrected for:

Atmospheric effects: As radiation from the land surface passes through the atmosphere to the sensor, it is

affected by absorption by the atmosphere. This is related to the transmittance and emittance of the

atmosphere and varies with temperature and humidity. Given the low altitude, and the warm, dry conditions at

the time of the flight, these effects are likely to be relatively small (Figure 7).

Emissivity: Surface temperatures are influenced by the emissivity (the ability of a surface to emit radiation).

Surfaces with a low emissivity appear cool when they may in fact be warm. This is especially evident for

rooftops (e.g. corrugated iron) where emissivity is very low. Current procedures for dealing with emissivity

correction for high resolution thermal imagery are inadequate, though is probably the largest source of error.

Directional effects: The sensor actually ‘sees’ surface radiation from multiple directions and those

temperatures from surfaces that are ‘off-nadir’ may appear cooler than those surfaces located directly

perpendicular to the surface (e.g. viewing a thermal image of a wall, the apparent temperature of the wall

may change at the edges of the image, when in fact the temperature is the same). Topographic changes can

also be corrected for.

The implication of this is that the actual surface temperature values observed by the sensor are not precise and

can be several degrees out. Addressing these corrections increases the cost associated with capture and postprocessing. The thermal maps provide an idea of the relative differences in surface temperature rather than

absolute temperature differences.

Figure 7: Demonstration of the effects of different corrections applied (e.g. atmospheric and direction corrections listed above) for a

transect across the city of Vancouver BC. Directional brightness is equivalent to the data provided to Geelong and Wyndham. These

data are a coarser resolution, but demonstrate the uncertainty of not undertaking corrections (Voogt and Oke, 2003)

Plan view only: The image only provides a bird’s-eye-view of the surface, and so does not capture the full 3D

nature of the urban environment which influences urban micro-climates.

Snapshot in time: Land surface temperatures at this high resolution are clearly highly variable spatially, but also

temporally. Surface temperatures will change with different times of capture, different meteorological conditions,

and changing surface conditions (e.g. soil moisture). This makes meaningful comparisons of images over time

difficult. It is not really possible to establish a ‘baseline’ dataset of surface temperature.

Surface-air temperature relationships: The key assumption in using thermal data for urban climate analysis is

that air temperature patterns follow land surface temperature patterns. However, Tomlinson et al. (2011) states

that “a significant research gap still exists which is the quantification of the relationship between measured air

temperatures and remotely sensed LST data”. This is especially true at the micro-scale for high resolution thermal

data. Wind speed and atmospheric stability influence correlations and they are poorer during the day when the

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

34

atmosphere is unstable and turbulence is higher. As an example, surface temperatures may be high next to the

ocean, but air temperatures would be low due to sea breezes.

Building energy efficiency: This thermal data cannot be used to identify poor performing buildings in terms of

energy efficiency. The uncertainty with emissivity means that rooftop temperatures are not precise. Also, surface

temperatures are just that: they do not give an indication of the insulating effects of buildings or their energy

efficiency.

Data quality: Quality data collection is essential. The data quality of these images appears very good. Flight need

to be conducted progressively over the target area (e.g. East to West). Obviously, an issue for Geelong is the time

taken for flights meant that the surface heated as the collection of data was undertaken. Taking N-S strips of data

will make presentation and interpretation of data easier. This has been an issue in other thermal mapping

exercises. A balance between resolution and flight time is needed. If smaller focus areas are identified for thermal

mapping, this reduces the time – flights should probably aim to be less than one hour in duration.

5.1.2

Further work

Thermal imagery: Identifying hot-spots in the landscape is good way to help prioritise investment in reducing

urban temperatures. In deciding on future thermal mapping exercises, it is critical that the objectives of mapping

are clear. If information is sought on a particular focus area for intervention (e.g. retro-fit), then high resolution

thermal imagery may be useful for this purpose to identify hot streets, or to target unirrigated areas, etc. but, the

limitations should be kept in mind. However, the imagery already collected provides information on the types of

surfaces and urban arrangements/designs that cause high surface temperatures, which is not likely to change. In

developing new areas and retrofitting existing areas, targeting areas with high solar access will help improve

human thermal comfort. In summary, the benefits of high resolution thermal mapping are dependent on the

objective of the mapping exercise. If mapping is to be undertaken again it should focus on target areas, consist of

short duration flights, and should be corrected as best as possible.

Mapping vulnerability: As noted earlier in the report, a heatwave vulnerability map could be developed that

made note of both the most vulnerable populations as well as the urban areas most likely to experience elevated

temperatures

Satellite imagery: An alternative approach is the use of satellite imagery. A variety of products are available at

different resolutions. LANDSAT has been used many times in studies of urban heat island. LANDSAT ETM+ data

is available from 1999 onwards, and can provide 30m resolution. There are limitations with LANDSAT data (i.e.

captured every 16 days, capture at 11am only, data from 2003 only 80% of scene available). An example of

LANDSAT ETM+ data is provided in Figure 8 below. While limitations exist, benefits include standardised

approaches for all the necessary corrections including atmospheric and emissivity corrections. The entire region is

captured simultaneously, eliminating effects of flight time that were seen for Geelong. A new LANDSAT satellite

has been launched and will become operational in 2013. This coarser data can still be used to identify hots-spots

in combination with aerial photography, and may be easier to identify though this approach. The coarser scale

probably means a better representation of air temperature variations too.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

35

Figure 8: Comparison of high resolution (0.5m) thermal mapping (left) versus 30m resolution of the same data (middle). LANDSAT

satellite data provides a similar image to the scaled up version here. The LANDSAT image (right) is for 11am 25 Feb 2012. The ‘hotspots

are in the same location as the high resolution thermal image, as are the cool spots. The white bands are the missing data.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

6.0

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

Urban Heat Island Report: City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council

36

References

Coutts, Andrew, Beringer, Jason and Tapper, Nigel(2010) 'Changing Urban Climate and CO2 Emissions:

Implications for the Development of Policies for Sustainable Cities', Urban Policy and Research,, First published

on: 06 January 2010 (iFirst)

Department of Sustainability and Environment (2008a), Climate Change in Victoria, Victorian Government,

Melbourne.

Department of Sustainability and Environment (2008b), Climate Change in Port Phillip and Western Port, Victorian

Government, Melbourne.

Forecast.id (2013a), Wyndham City Council Population Forecasts,

http://forecast2.id.com.au/Default.aspx?id=124&pg=5330, viewed 06/06/13.

Forecast.id (2013b), City of Greater Geelong Population Forecasts,

http://forecast2.id.com.au/Default.aspx?id=268&pg=5320, viewed 06/06/13.

Loughnan, Margaret, Nicholls, Neville, & Tapper, Nigel. (2009). Hot spots project: A spatial vulnerability analysis

of urban populations to extreme heat events. Retrieved 1 February 2013, from

http://docs.health.vic.gov.au/docs/doc/2BE6722DD7C4874ACA257A360024E0DE/$FILE/heatwaves_hotspots_pr

oject.pdf

Loughnan, ME, Tapper, NJ, Phan, T, Lynch, K, McInnes, JA (2013), A spatial vulnerability analysis of urban

populations during extreme heat events in Australian capital cities, National Climate Change Adaptation Research

Facility, Gold Coast pp.128.

Norton, BA, Coutts, AM, Livelsley, SJ, Williams, NSG (2013) Decision principles for the selection and placement

of green infrastructure to mitigate urban hotspots and heat waves. VCCCAR report. University of Melbourne and

Monash University.

http://www.vcccar.org.au/sites/default/files/publications/Urban%20Heat%20Island%20Decision%20principles%20

green%20infrastructure.pdf

Nury, S, Coutts, A and Beringer, J (2012), The spatial relationships between vegetation, built area and land

surface temperature distribution in the City West Water service area using satellite imagery, City West Water and

Monash University, Melbourne Australia.

Profile.id (2013a), City of Greater Geelong, http://profile.id.com.au/geelong, viewed 06/06/13.

Profile.id (2013b), Wyndham City Council, http://profile.id.com.au/wyndham, viewed 06/06/13.

Tomlinson, C. J., Chapman, L., Thornes, J. E. & Baker, C. 2011. Remote sensing land surface temperature for

meteorology and climatology: a review. Meteorological Applications, 18, 296-306.

Voogt, J. A. & Oke, T. R. 2003. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates. Remote Sensing of Environment, 86,

370-384.

29-Jul-2013

Prepared for – City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council – ABN: 38 393 903 860

AECOM

City of Greater Geelong and Wyndham City Council