WORD - Frozen Trail to Merica

advertisement

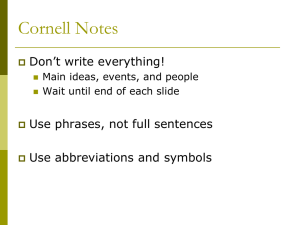

DECIPHERMENT OF WALAM OLUM Myron Paine, Ph D Ancient American Conference, 2007 Wilmington, Ohio Oct. 5-7 2000 DECIPHERMENT OF WALAM OLUM Myron Paine, Ph D Ancient American Conference, 2007 Wilmington, Ohio Oct. 5-7 2000 My purpose for this presentation is to persuade you that the Walam Olum was created by people speaking Old Norse. WHAT is the WALAM OLUM? The Walam Olum is a 600 year old Leni Lenape history which uses pictographs to trigger memory verses. The Lenape’s Walam Olum history is unique among North America Indian tribes. Most tribes have a short history, usually three generations or less. The Walam Olum pictographs were etched unto a flat thin stick of wood a little wider than a thumb and about as long as a thumb. A historian would select a pictograph and then recite the associated memorized verse. The next generation historian learned the memory verses and copied his set of memory verses. A typical pictograph from Chapter 2 of the Walam Olum, the flood, is shown below. There is a verse associated with this pictograph that identified the large women as Manito’s Daughter. ”Manito” means, “creator” in Old Norse. The three spikes on her head may mean the “father, son, and holy ghost.” The full rounded body of Manito’s daughter appears to be associated with all of the Manito’s helpers in the pictographs. 2 HISTORY of WALAM OLUM The history of the Walam Olum began in 985 when Eric the Red led fourteen boats to the Eastern and Northern settlements of Greenland. In the year 1000 his son Leif created a settlement in America. The Walam Olum describes the division of the Greenland people into homesteaders, those who remained in Greenland, and hunters, those who roamed everywhere. In 1121 Bishop Gnuppson left the Northern settlement and never returned. He may have settled at “East Man” on the eastern shore of James Bay. Even today the river is called “East Main.” “Man” means, “people” in Old Norse. The Bishop probably called himself “Paafa Gnuppson” meaning “Father Gnuppson.” Thirteen years later a second Paafa, Arnard, also left the Northern Settlement to continue Paafa Gnuppson’s mission. The next Bishop to Greenland shifted the Bishop’s residence to Goddard, which was located at the head of Herein Fjord. “Hrein” means “pure: in Old Norse. Even today the modern Norwegian dictionary has the definition of “rein” as “pure.” An alternate spelling is “ren,” A common Old Norse phrase is “aa buui,” which means to “abide with.” As the centuries pasted, “aa buu” began to sound similar to “ape” spoken as two syllables. So the word “renape” may have meant “abiding with the pure.” The use of “Renape” may have started in Hrein Fjord, but as more people became “pure” in Greenland and in America the phrase applied to any community of people who were pure. 3 FIRST TWO CHAPTERS Some time after Paafa Gnuppson arrived at East Man someone created the pictograph and memory verse scheme so the local paafas could tell the creation story and the flood story during the evening campfires. The creation story appears to be based on the Biblical creation story, except the biblical snake turns into the evil Manito. Many tribal myths use the good and bad creators as a way to explain good and bad in the world. There were also similar good and bad creators in Europe. The flood story seems to be further removed from the biblical flood. There is more involvement with a serpent similar to the serpent that Odin and his friends fought. CHAPTER 3: MIGRATION Little Ice Age During the Little Ice Age Davis Strait froze more than nine months in 27 out of 60 years. The cold years occurred together for usually nine out of every 14 years. During the cold periods the major reliable source of food was the open water marvels in Ungava Bay. Open water marvels were places where the sea did not freeze. They are caused by an interaction of high tides and shallow beaches. There are about nine open water marvels in Ungava Bay. In 1346 one thousand Renape migrated across the ice to East Mans. Three thousand more Renape made the migration from the Eastern Settlement in the following years, The Renape of the each migration moved south to find food and to ease the burden on the East Man people. 4 Somewhere, in a place they called Evergreen Land, the leaders of the migration must have discussed recording the miraculous salvation of the Renapes. Perhaps an old Paafa suggested the pictograph and memory verse method. So a third chapter of the pictographs was created. The third chapter told of Greenland history and the migration across a frozen sea. CHAPTERS 4 AND 5 TWO HISTORY CHAPTERS Travels through Ohio The collapse of the Lenape The Lenape moved south to a center just north of the Great Lakes, then further south into Michigan and Ohio areas. There they grew in number. Two centuries after the migration chapter was created, the Leni Lenape lived on the east coast of North America from the Carolinas to upper New York. They continued to record their history by the pictograph and memory verse method. The historians were called”aarum tids,” which means “Yearly time.” The pictographs for the most outstanding events were slipped into the permanent record, which was called the “Maalan Aarum” for “Recorded years.” Two groups moved to the east. One group went to the New York area and up the Hudson River. The second group slipped through a southern pass. They went to the Chesapeake Bay area and down the coast as far as North Carolina. Two or more families of tribal aarum tids copied the Maalan Aarum and recorded the events of each major group. These histories became chapters four and five of the Maalan Aarum. Both Chapter 4 and 5 have a verse about seeing white people in big boats. The first episode may have been in the 1500s. The Lenape people met the boats when the Europeans arrived in Roanoke, Jamestown, and Manhattan. The historic records all indicate that the Lenape behaved friendly in every case. The Maalan Aarum ends abruptly, about a century after the first white man episode, with the second recorded episode of seeing white men. But the Lenape world began to collapse. 5 The Lenape were pushed back to the Alleghenies. When France lost the War of 1763, they did not really occupy the land in America but they surrendered all the land the Lenape's occupied west of the Alleghenies to the British The British promised to contain white settlers east of the Ohio. The British could not. Then the British and the Lenape tried to stop the European settlements but Britain lost the Revolutionary War. Once again Lenape land was given away by British to Americans. A last spasm of fighting occurred during the War of 1812. Britain could not support the Lenape fighting for their land. So by 1820 the Lenape tribe had shrunk to a small group of disheartened, discouraged, and disorganized people clustered in central Indiana. (See small circle at the tip of arrow in the collapse of the Lenape figure.) Lenape men had fought for all sides, French, British, and American. There was a chaotic period of insane revenge killings among the Lenape. But the greatest disagreement was between the young angry men and the old discouraged leaders. One recorded episode tells of a young man throwing his live father onto a roaring campfire and roasting him to death. In this insane chaos, an older historian sensed he was near death and sought treatment from the Americans. Dr. Ward of the Americans eased the pains. The historian passed the pictographs of the Walam Olum to Dr. Ward. ORIGINAL TRANSLATION Dr. Ward passed the sticks on to Professor Rafinesque at the Transylvania University in Kentucky. I will refer to Rafinesque as “Editor.” The Editor located two, or more, missionary priests. These were Monrovians, who seemed to be able to speak the Lenape language easier than English or French speakers. I will call the Monrovians, the “Recorders.” The Recorders were able to locate another old Lenape Historian, who could recite the verses. So they began a prolonged episode of recording the sounds associated with 183 pictographs. The Historian and the Recorders tried to work out the English translation of the sounds. The evidence is that the Historian knew more English than the Records knew the Lenape language. For example, in the second verse of Chapter 3, the Historian tried, twice, to tell the Recorders that “it was winter where they abode.” The Recorders misspelled the same word two different ways and translated the two misspelled words as “icy” and “freezing.” They obviously did not know the Lenape word for “winter.” Two other redundant recorded sounds appear to be attempt by the Historian to explain “winter”. The recorders may have had other handicaps that affected their objectivity. They probably knew of the strong turtle clan among the Iroquois and also a lesser turtle clan among the Lenape. They may have also heard about the snake rituals of the Southwest 6 natives. The Lenape words for turtle and snake are simple two syllable words. The Recorders appeared to miss the recording of sounds from other Lenape words that sound similar to those Lenape words. The recorded sounds and the original English translations were returned to the Editor who spent more than a decade to try to understand the pictographs and the language. The Editor had his own bias to add to the Walam Olum. He was a strong believer in the then popular theory that all natives of America migrated across the Bering Strait. There is evidence that the Editor did alter the original recorded sounds so that the people in his publication of the Walam Olum were going to the east instead of west. There is also evidence that the Editor may have doctored the pictographs. He may have added a head and a tail to the symbol for the “ground left behind.” He probably thought a better representation of a turtle would make the turtles created by the Reporters more believable to English readers. He overlooked changing a few symbols for the “ground left behind.” So, the “turtle” symbols are inconsistent. Besides, if the Editor had really understood the Walam Olum, the “turtles” would be going in the other direction. The Walam Olum we read today was filtered through four centuries of historians, Recorders who did not translate faithfully, and an Editor with a biased view of history OLD NORSE Reider T. Sherwin was a Norwegian, who grew up on a remote island in Norway. His first language was a dialect of Old Norse. Sherwin came to Northeast America as a young man. When he and his friends went touring, he discovered that the signs naming places used the same words that he would have used. Sherwin became focused on finding out if the Indian names were really Old Norse names. Then he became focused on word lists from 25 tribes that were written down by eighteen translators. Sherwin would search for words that had similar sounds and meanings in the different tribes. When he found two tribes, or more, with words having the same sounds and meanings, then he would try to find an Old Norse phrase that also had the same sounds and meanings. 7 In 1940 he published his first book “The Viking and the Red Man” in the prelude to World War II. In that book he had over 2500 comparisons between the Algonquin and Old Norse. Through out World War II Sherwin, who was retired, kept his focus. For fourteen more years he compared Algonquin and Old Norse phrases until he had eight volumes under the same name and over 15,000 comparisons of Algonquin and Old Norse. In his forth volume, he wrote the forward himself and said, “The Algonquin Indian Language is Old Norse.” A few lines later he wrote “… the truth cannot be denied.” But it sure was ignored! DECIPHERMENT After I started to write the Frozen Trail to Merica, I decided I had better check with Sherwin to see if the Walam Olum might have derived from Old Norse. One evening I deciphered the first verse of chapter 3. All the sounds, except the first, agreed with Algonquin words and the Old Norse comparisons had English meanings similar to the original translation. Then, after a careful search of Sherwin’s comparisons I found an Algonquin word that may have made the original recorded sound, but the sound dropped a syllable. After reflecting on four centuries of memory cycles, I thought it was amazing to lose only one syllable. So, with relief, I laid my pen scribbling aside and focused on finishing my book. Years pasted. At last I had a finished manuscript mailed to a publisher. Then I had to wait. While I waited last December, I wondered, “Can I use Sherwin’s 15,000 comparisons to decipher all of the verse of chapter 3?” DECIPHERMENT EXAMPLE Original sound to Algonquin Algonquin to English 8 As an example of the decipherment process, look at Walam Olum chapter 3 verse 7 figures above. I chose to use this verse for an example because it had only six sounds, because there were no dropped syllables in the Algonquin/Old Norse decipherments, and because the Original English and the decipherment English were similar--with one exception. In the original sounds to Algonquin figure, the English text as written by the Recorders is shown above the original sounds. The bottom word in each of the three sets of sounds is a valid Algonquin word as recorded by Reider T. Sherwin. There is an exact sound “tulpe” in Algonquin and it does mean, “turtle.” But the original English appeared to have an unusual amount of “turtles,” “turtleland,” “snakes” and “snake land” through out the whole Walam Olum. Besides a turtle land in the north did not seem congruent. I made a hypothesis that the Recorders were focused on turtles and snakes. So where ever those words occurred in the original English I tried to find another Algonquin word that had similar sounds to the original sounds. In every case the other Algonquin word made better sense in the final English version. In the Algonquin to English Figure, the original English and the sounds have been replaced by the Algonquin word and the Old Norse word that Sherwin chose as sounding close to the Algonquin word. The English phrase at the bottom of the three sets is the English from Old Norse/English dictionaries that Sherwin consulted. Compare Original vs. Deciphered English In the figure above the original English text is compared with paraphrased English from Old Norse/English dictionaries. Two of the three sounds have a roughly similar English meaning, but the “turtle” and the “left behind” ground have distinctly different meanings. An earlier, frozen ground which was left behind implies the Lenape migrated from a northern country. 9 Original sound to Algonquin Algonquin to English The two figures show the development for the second group of three sounds. Notice that two out of the three original sounds have the exact sounds as Algonquin words. I believe this is strong evidence that the Walam Olum story was repeated for generations in the Algonquin language. Note the last two set on the Algonquin to English figure. The “immersed be” and “pure be” are Old Norse syntax. A modern paraphrase meaning would be “immersed to be pure.” Compare Original vs. Deciphered English The comparison of the original English with the Decipherment English reveals the major error the Recorders made. They moved the Algonquin sound for “pure be” – “linapiwi” – up to the top line and used it as the people’s name, “Lenape.” Because the recorders did not understand that “Lenape” meant “abide with the pure,” and because they were fixated on turtles, they obscured the “immersed to be pure” emphasis of the verse. 10 Paraphrase of Old Norse The English paraphrase of the Old Norse words gives a much improved sense of the original pictograph. Six hundred years ago the creators of the migration chapter were trying to tell about the Bishop of Greenland having control of all the land. This was the time when Popes, Cardinals and Bishops were the king makers. In 1245 the church council of Lyons had deposed King Fredrick II of France. The Pope appointed the Bishop to Greenland. There was no King. The Bishop’s wishes over rode the Althing, an annual meeting of the leading men. If the Recorders had been able to decipher the verse correctly, their credibility would have been challenged. They might have asked: “Are we facing an old historian who is trying to tell us that a Bishop, who was immersed to be pure, controlled that earlier, frozen country the people left behind? “If “lin” means pure, then are these people calling themselves “Leni Lenape,” really saying I am “pure abiding with the pure?” “If the pure are immersed to be pure, which is the same as many Christian baptism rituals, does that mean they are Christians? “Oh my God! Are we Christians persecuting people who think they are pure – like Christ?” I have just shown you one example of how Reider /T. Sherwin’s 15,000 comparisons of the Algonquin Indians Languages and Old Norse can decipher the Walam Olum. Twelve verses consisting of 82 recorded sounds which derived from 144 Old Norse words have been deciphered and put on the Frozen Trail web site. http://www.frozentrail.org Except for the turtles, snakes, snake land, and a few other minor animal name changes, the original English translation and the English derived from Old Norse words appear to have similar overall meanings. 11 So I grew confident that Sherwin was correct in saying that the Algonquin Language was Old Norse, and the Walam Olum was created by someone who spoke Old Norse. I had ever increasing confidence for the first twelve verses! Then I hit the thirteenth verse. As fate would have it, I chose the pictograph for the thirteenth verse for the first page of the Frozen Trail to America: Talerman. The original English words said, “Floating up the streams in their canoes Our fathers were rich. They were in the light, when they were is those Islands.” That English verse looks innocent enough, except perhaps the phrase “Floating up the streams.” But my English paraphrase of the Algonquins/Old Norse decipherment came out to be: “You flock of buzzers, which little bit will you snicker at? I told you we had a ruling priest in the light on the other side.” No floating. No streams. No canoes! I could not come up with a similar over all meaning to the original English. After twelve verses the mismatch of the original English and the recorded Algonquin words is another indication that the original Walam Olum sounds are authentic. No intelligent person in the nineteenth century could have devised a “flock of buzzers” to describe a man in a canoe. Nor am I likely to be incorrect in the decipherment. Eleven (11) translators from eleven (11) Algonquin tribes reported that “flock of buzzers” meant “swarm of bees.” The Algonquin word is “amok.” I have not had time to investigate where “running amuck” came from, but amok looks like a contender/ 12 The Recorders apparently did not realize that the Walam Olum sounds did not match the pictograph. The Historian may have said the incorrect words deliberately to inform those who really understand Algonquin that the recorded English version was not valid. Or the Recorders may have copied those sounds as the Historian expressed his dismay and anger over the proposed English explanation of verse. Their extra page of recorded sounds may have been paired with the pictograph instead of the correct memory verse. Whatever happened or why it happened, the verse for pictograph 13 is very strong evidence that Recorders were trying to write sounds of a language they did not truly understand. Mistakes like this are extremely difficult for someone trying to solve the puzzle without having Sherwin’s comparisons for reference. So what does all that mean? The Walam Olum, Chapter 3 does describe Greenland and the migration from Greenland. The Walam Olum migration chapter was created by people, who spoke Old Norse. The creators knew how to describe Greenland, elements of the Christian religion and the power of a European Christian Bishop. The Walam Olum creators probably walked over the Ice during the migration, so the persons must have been working on the engraved sticks and verses about 1380. The Walam Olum migration chapter created one hundred and ten years before Columbus sailed. So the Walam Olum story may have been two and a quarter centuries old when the Europeans arrived in North America. In the verse thirteen, the word “Lini” meant pure. The modern Norwegian dictionary defines “ren” as “pure.” “Pure” is an expression often used for a Christian conversion at baptism. “Pure” may have also been the Algonquin word for being baptized. 13 WHERE THE OLD NORSE LIVED ALGONQUIN/OLD NORSE RANGE Look at the map showing the Algonquin speaking people in North America. Notice that they occupied most of the territory from the front range of the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic coast in both the United States and in Canada. Thus the Norse had a gigantic impact on America. Dialects of the Old Norse language spread from the Rockies to the Atlantic, from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico. There are literally tons of evidence that the Old Norse were in America. The decipherment of the Walam Olum by using Old Norse words establishes a vast region of Norse artifact credibility. A Norse artifact found anywhere in Algonquin country is now “in context.” Rune stones from the fifth century Heavener stone, to the medieval spirit pond stones, to the almost historic Kensington stone lay on land where Norse men walked. Those people who argued that they were foreign objects “out of context” have delayed the true understanding of America for centuries. Like a big puzzle, the artifacts, the biology, cultural traits, history, and language are fitting together faster and faster. The decipherment of the Walam Olum using Old Norse words is similar to the key piece of the puzzle that reveals the vast area of long time Nordic influence in North America. CONCLUSIONS The WALAM OLUM has a GREENLAND chapter WALAM OLUM was created by people who spoke OLD NORSE The ALGONQUIN languages are dialects of OLD NORSE NORSE artifacts are in context within ALGONQUIN territory 14