ADAMAWA JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT AND

DECISION ANALYSIS

(ADSJOMADAN)

ISSN 0875-6976

Vol. 1 No, 2 July, 2008

Publication of Business Administration Department Adamawa State

University, Mubi P.M.B. 25 Mubi, Adamawa State-Nigeria Email:

adsuioumalofmda@yahoo.com.

© 2008 Adamawa Journal of Management and Decision Analysis, All

Rights Reserved. First Published in January, 2008.

i

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editor:

Associate Editor:

Secretary:

Marketing Managers:

Circulation Manager:

Legal/Advisory Committee:

Dr. E. O. Oni

Department of Business Administration,

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

Dr. B.Y. Maiwada

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi

Bananda Robinson

Department of Business Administration,

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

John Itodo

Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

John Ldama

Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

Alh. Umar Usman

Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

Hajiya Fatimah Usman Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

Barrister Magai V. Magai Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

Barrister Dan. O. Asogwa Department of Business Administration

Adamawa State University, Mubi.

COPYRIGHT

Copyright is vested in Adamawa Journal of Management and Decision Analysis. However, permission to use

articles in this Journal for the purpose of teaching, research and academic discourses given on the condition that the

source article(s) is duly acknowledged and documented.

INDEMNITY

The views expressed or ideas reported in articles published in this Journal are those of the author Authors are

therefore strictly responsible for any violation of copyright.

CONSULTING EDITORS

Prof. Lante Nassar

Department of Management and Accounting. O. A.U. He Ife

Prof. Walter Ndubisi

Department of Business Management University of Maiduguri

Prof Ayuba Aminu

Department of Business Management University of Maiduguri

Prof. Haruna Dlakwa

Department of Political Science and Administration, University of Maiduguri.

Dr. G.O. Atoyebi

Department of Economics. University of Ilorin

Dr. Jackson Olujide

Department of Business Administration, University of Ilorin

Dr. S.A. Adebola

Department of Marketing. Babcock University, Ilisha Remo, Ogun State.

Dr. (Mrs) Teresa Nmadu Department of Management Sciences, University of Jos.

Dr. lyeli I. lyeli

Department of Economics. University of Port Harcourt

Dr. J. J. Adefila

Department of Accounting University of Maidugurri

Dr. W. N. Tagowa

Department of Political Science and Public Administration Adamawa State University,

Mubi

Dr. M.I.Bazza

Department of Business Management. University of Maiduguri

EDITOR'S NOTES

Adamawa Journal of Management and Decision Analysis is a product of dream of the lecturers in the Department of

Business Administration. Adamawa State University, Mubi. We have a dream to further inspire the University academia to

provide leadership in the generation of fresh and qualitative ideas.

The general objectives of Adamawa Journal of Management and Decision Analysis among others is to launch

updated insights into the field of Management. Business and Social Sciences by exploring an integrated development issues

in the areas of research learning and community service. In addition, the Journal will further research, and redefine popular

focus where need be and offer policy makers empirical options within the scholastic framework. Also it will provide avenue

for comparative research with a view to come out with new ideas on the existing debates or researches.

The views and opinions expressed in this journal continue to be entirely those of the contributors and not necessarily

those of Adamawa State University. Mubi.

The Editorial Board remains committed to all as we promise to come out twice a year, January and July. We are

sincerely grateful.

E.G. Oni Ph.D

Editor

TABLE OF CONTENTS

S/NO

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

TITLE

PAGE NUMBER

Editorial Board

ii

Copyright

ii

Indemnity

ii

Consulting Editors

iii

Guidelines for submission

iv

Editor's Notes

V

Access to University Education And Attrition Rate in

1

Nigeria - an Assessment of the Case of Disadvantaged Groups

Solomon A. Adebola, and E.O. Oni

The Challenges of Changing Attitude in Business Organization for Restructuring and

3

Development of Nigerian Economy

Ejika Sambo

Risk Return Trade Off and Management of Risk and Uncertainty in Business

19

Enterprises

Maiwada Y.B. And Knights E.D.

Impact Assessment of Marketing Channel Decisions

25

on Performance of Organisation in a Volatile Economy

Aremu M.A.

Diversification of Energy Sources FOR Sustainable Economics Development In

36

Nigeria: The Role of Coal

Balogun, I. O. And Dada, S.S

Collective Bargaining: The Nigerian Perspective

47

Dr. J. A. Bamiduro

Consolidation Effects and the Value Gains in A Post-Merger Financial Institution: A Co 46

Of United Bank For Africa (UBA) Plc

A. U. Alkali And Umar Usman

An empirical Evaluation of the Poverty Alleviation Strategies in Nigeria

63

Dr. Omeiza, O.U. Yisa

Organisational Structure and Control Strategies in Asian Multinational Enterprises

70

Operating in Nigeria

Dr. A.L Badmus And T.K. Aluko

Empirical Analysis of Entrepreneurship Capital and Economic Performance in

75

Nigeria

Dr. E.O. Oni and Dr. G.O. Atoyebi

Marketing of Tourisms for Rapid Development in Nigeria

86

Bananda Robinson

The Implications of Corruption on National Development in Nigeria

92

Saidu Tunenso Umar

Information Technology Utilization in Educational Sector

102

C. Y. Ogbonyomi

Assessment of Tax Budget and Administration in Nigeria: An Analytical Review of

106

1996-2003

Dr. J. J. Adefila and Mr. A.A. Ahmed

Nigeria 's Macro-Economic Management Strategies for Economic Development and

116

the Way Forward

Eli H. Tartiyus and Papka Z. Medugu

Micro-Economic Estimation on the Demand Function for Prostitution in Adamawa

120

State

Ibrahim Baba lya

Total Quality- Management In Nigerian Oil Marketing Company: A Study on-Mobil

123

Nigeria Plc

R. A. Gbadeyan and J.O. ADEOTI

iv

24.

25.

26.

27.

Impact of Globalization on Export Performance in Nigeria

Mohammed Inuwa Dauda

The Strategic Importance of Internet Banking IN Nigerian Financial Institutions

Dr. (Mrs.) Sidikat L. Adeyemi and Mr. Mukaila A. Aremu

Re-Examining The Causes of Bank Distress in Nigeria: A Safety Net Panacea For The

Effective Management of Banks

John Itodo And Ormin Koholga

Staff Quality, Products Quality and Efficient Delivery as The Tripod of Total Quality

Management In Organizations

Ldama John

v

129

138

149

161

GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION AND ACCEPTANCE

Contributors are invited to submit their manuscript for publication in Adamawa Journal of Decision Analysis.

Research papers are assessed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Authors whose articles have been accepted for

publication will be notified immediately. Those articles that are poorly presented would be returned to the authors after

assessments.

The Journal deals with contemporary and emerging issues of Business, Economics, Finance, Marketing,

Management, Portfolios Management, Public Relations, Strategies and practices as related to the developing world,

production and operation management, e-commerce, MIS, Insurance, ICT and business application, policies and

regulations, ethics of business, ecology of business e-governance and other areas. " Manuscripts

should

be

submitted electronically as attachment through our email: Adsujournalofmda@yaoo.com or submitted

three clear of the manuscripts with a CD containing it to the secretary Adamawa Journal of Management and Decision

Analysis, Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, M.M.B. 25, Mubi.

Manuscript should not exceed 16 pages in length including abstract and references typewritten double-spaced

on A 4 paper with margin on both sides. The title page should contain the title of the article, name(s). Submitted

manuscripts are circulated for review without the author's name and institution identification. Manuscripts are received

on the understanding that they are original and unpublished works of the author(s) not considered for publication

elsewhere. Authors are encouraged to describe their findings in terms intelligible to the non-professionals/experts

reader. AH works cited in the text must be listed under references in alphabetical order (the author's name and the year

of publication).

vi

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

Volume I Numbe 2

July, 2008

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING: THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE

Dr. J. A. Bamiduro

Department of Business Administration, University of llorin, llorin.

Introduction

In Nigeria, as in many West African countries, wage employment had not always been in practice. The head of the family, in

this case, the father, was the head of 'economic affairs' of the family. It was he who planned what the family should do, the

type of farming and the size of the farms as well as where to sell the harvested products. His children and wives helped in this

process. No external recruitment was involved. Where a man was able to hire labourers to help in the farms, payment was in

kind, that is, feeding, clothing etc. However, the situation as pictured above, started to change as a result of the advent of

commercial organization in Nigeria brought about by the need of colonial administration to see that necessary labour for its

developmental activities for building railways, for constructing of administrative building, and for the mining of coal to

secure necessary labour. In order to assist in the process. Nigerians were employed as workers, and unlike in the 'family'

arrangements, they were paid for work done. Wage employment was not confirmed to the private sector alone, because the

civil service was established and government activities such as the laying of the railway line from Lagos to the North with the

attendant employment of Nigerians led to payment of wages. Thus, wage employment made gradual inroad into the situation

as a result, of the breakdown in customary labour system in the early 1920s in Nigeria.

With this development, it is pertinent that collective bargaining arrangements had to come in. In Nigeria before

1973, union recognition was achieved through bargaining agreement. Sometimes the agreement is achieved through an

unstructured bargaining, that is, bargaining without clearly worked out procedures. This paper examines the concept and

principles of collective bargaining, looks at the employment distribution in Nigeria resulting into employment law and

various collective bargaining arrangements. It therefore concludes that collective bargaining offers both an opportunity and a

challenge especially to union leaders and our policy makers in Nigeria.

Distribution of Employment in Nigeria

Generally, industrialization in Nigeria grew rapidly in the 1970s but the contribution of the industrial sector to

employment growth has been disappointing. While gross value added in manufacturing increased at an annual rate of 14.1

per cent, the number of employees in manufacturing increased annually only by 5.7 per cent (Morawetz 1974) This slow

growth rate of employment could be explained by the MNCs' choice of capital-intensive production! techniques. Sectoral

distribution of employment (Table 1) shows that agriculture, distribution and manufacturing I continue to dominate total

employment in Nigeria with average shares of 58, 16 and 10 per cent respective!}. Nevertheless, distribution, services and

manufacturing are much more significant when only wage employment is considered.

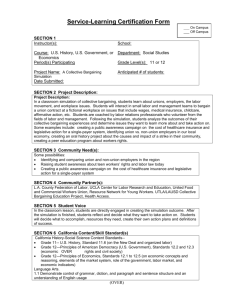

Table 1: Total Employment By Sector In Nigeria, 1960 -1996.

Economic

196

197

1975

1980

1985

1990

1992

Sector

1.

Agriculture

71.7

69..8

64.0

60.0

57.8

60.7

59.8

59.8

2.

Mining

0.2

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.5

0.5

3.

Manufacturing

9.6

12.2

16.8

17.0

18.2

10.0

10.5

10.5

4.

Building

Construction

0.6

0.6

0.9

11

1.2

1.0

1.0

1.0

5.

Electricity,

Gas and Water

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.2

0.2

1.2

1.2

1.2

6.

Distribution

12.9

12.6

12.2

16.0

16.1

16.3

16.3

16.3

7.

Transport and

Communication

0.8

0.8

0.6

0.6

0.6

1.5

1.5

1.5

8.

Services

3.9

3.9

5.0

5.6

5.6

9.0

9.2

9.2

Source: Compiled from various documents of the National Manpower Board for the ILO (2000).

1994

1996

59..8

0.5

10.5

1.0

1.2

16.3

1.5

9.2

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

46

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

Volume I Numbe 2

of particular importance in the private sector are the

activities and employment behaviour of the multinational

companies (MNCs). They differ from other business firms

to the extent that they control large sums of investment

unavailable to indigenous enterprises.

In Nigeria, such MNCs entered into joint

ventures with small group of Nigerians who have the

means to acquire shares allotted to them. Consequently

even though the MNCs in Nigeria have changed their

trading or operating names and ownership, they have not

changed their character, neither have they severed the

fraternal relations with their home offices (Bierstecker.

1987). This invariably affects their collective bargaining

procedures.

Employment Laws in Nigeria

The Labour Act Cap. 198 Law of the Federation

of Nigeria 1990 repealed the Labour Code Act Cap. 91 of

1958. The Labour Act now incorporates the Labour

Decree No. 21 of 1974; the Labour (Amendment) Decree

No. 21 of 1998; the Trade Unions (Miscellaneous

Provisions) Decree No. 17 of 1986; the Labour

(Amendment) Decree No. 17 of 1988; and the Trade

Unions (Miscellaneous Provisions) Decree No. 25 of

1989.

Part (I) of the Labour Act, that is sections 1-22 deals with

the general provisions as to the protection of wages,

contracts of employment, terms and conditions of

employment.

Part (II) deals with recruiting sections 23 to 48 etc.

Section 9(6) provides that as contract shall:

(a)

make it a condition of employment that a worker

shall or shall not relinquish membership of a trade union

or worker.

(i)

By reason of trade union membership or

(ii)

Because of trade union activities outside working

hours.

July, 2008

Terms and conditions 01 employment are dealt with under

section 13, such as normal hours of work. It states that

normal hours of work in any undertaking shall be those

fixed:

(a)

by mutual agreement; or

(b)

by collective bargaining within the organization

or industry concerned or

(c)

by an industrial wages board where there is no

machinery for collective bargaining.

There is also provision for excess of the normal

hours as overtime, rest interval and working week.

Collective Bargaining Concepts and Principles

From the foregoing, the promotion and

development of collective bargaining has often been

proclaimed as one of the major concerns of Nigerian

Labour policy.

Flanders (1965) takes the concept of collective

bargaining to mean a method of settling the terms and

conditions of employment and it involves in the first

place, employees acting together (through trade unions)

and the final agreement reached with the employers has a

regulative effect and imposes limit on the employers'

freedom of action in their relations with all their

employees covered by the agreement. DeCenzo and

Robbin (1996) are of the opinion that the term typically

refers to the negotiation, administration and interpretation

of a written agreement between two parties that covers a

specific period of time.

Armstrong (1999) opined that "collective

bargaining arrangements are those set up by agreements

between managements, employers associations, or joint

employer negotiating bodies and trade unions to erermine

specified terms and condition of employment. for groups

of employees. Bargaining therefore, is the process by

which the two opposing sides labour and management

reach an agreement on the terms under

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

47

Adamawa State University Jcurns! of Decision Analysis

Volume 1 Number 2

which they will operate for a period of time. Neither is

able to unilaterally impose its will on the other, so both

must seek a mutual accommodation.

Collective bargaining processes are usually

governed by procedural agreements and results in

substantive agreements and agreed employee relations

procedures. Overall, to the extent that collective

bargaining represents bilateral relationship which

involves dialogue, it can be taken as a prerequisite for

industrial harmony and industrial democracy. It has been

suggested that it is only through collective bargaining that

involvement and commitment of parties in an industry can

be secured with a view to achieving greater efficiency and

higher productivity (Omole, 1983). principles off

Collective

Bargaining

The principles of collective bargaining should

not only aim at advancing the objectives of the given

organization but also consistent with the continued

development of a relatively free, competitive economic

system (Adeoti, 2000). Accordingly, the following

principles are often listed:

1.

Acceptance:Management must accept the

labour union as the official representative and watchdog .'

the employee-: interests. The union must accept the

management as the primary planners and controllers of

the company's operations.

2.

Voluntarism:- Both parties must subscribe to

the principle of free collective bargaining and free

enterprise consistent with the advancement of public

interest. Neither of the two parties should want to

substitute outside force or governmental control for the

usual pressure of the marketplace.

3.

Problem solving:The problem-solving

attitude of collective bargaining emphasizes the legalistic

approach. The concern is less on finding loopholes in the

contract to the detriment of the other part)' and on relying

exclusively upon the lawyer to develop and preserve the

union-management relationship. The problem-solving

attitude recognizes mutual interdependence between tht

two parties.

4.

Democratic Accountability:Both panic

must be mindful of obligations to the principals in the;

situation. For the union, the principal is clearly the union.members for whom the organization was formed. The;obligation requires the adherence to democratic

processes, in order that the union may be truly responsive

to its members. Management has many principals among

whom are stockholders, the public, customers and ever

the employees.

Functions off Collective Bargaining

Collective bargaining is a method of furthering

basic union purpose, which is to maintain and improve

working conditions. It is a method of determining terms

and conditions of employment. The other methods are

unilateral determination by the State, employers or the

workers. Each of these methods are however inefficient as

they tend to result in the alienation of one of the parties.

Bargaining, therefore, is value jointly and severally to

each of the actors in industry.

To The Workers

Collective bargaining is the alternative to and a

replacement of individual weak attempt at bargaining The

terms and conditions are encoded In a collective

agreement and the provisions bind present as well as

future employees, unless otherwise reviewed.

Collective bargaining affords the employees an

opportunity to participate in the management functions of

their organizations. The absence of collective bargaining

implies that managerial prerogatives would dominate

most labour matters. Furthermore, collective bargaining is

the process of making rules that govern the workplace.

Such rules, substantive and procedural, are jointly

determined by both union and management and

sometimes with government. Substantive rules pertain to

financial issues. Procedural rules refer to the process for

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

48

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

Volume 1 Number 2

reviews of collective agreements, periodicity of

meetings, and methods of disputes settlement.

An extension of these functions, is the

provision for grievance and disputes settlement

procedures. For example, some collective

agreements specify the time at which impasses

during negotiations can turn into strike actions.

Uniform grievance procedure ensures the avoidance

of multiple standards in the administration of

discipline.

To The Employer

The functions of collective bargaining and

the value to the employer are often ignored in most

literature.

Collective bargaining is of the following important

values to the employer:

(i)

It saves the cost of negotiating with each

worker,

(ii)

It simplifies the salary administration

system.

(iii)

It tends to generate industrial harmony and

thus saves the cost of strikes.

(iv)

Jointly authored rules tend to be complied

with easily.

(v)

It provides a grievance procedure which

prevents the deployment of multiple standards by

management in treating indiscipline, and

(vi)

Avoidance of comparability issues that may

be raised by workers if individual bargaining had

been used.

Collective bargaining saves executive time

negotiating with individual workers. There are

associated financial costs in implementing a

complex system of individually negotiated salary

structure. Time thus saved can be spent on other

important management functions of planning,

coordinating, directing and motivating.

To The State

The value of collective bargaining to the

state derives in part from its value to the other two

July 2008

actors to the extent that they are directly connected

with the tempo of industrial relations. Peaceful

industrial relations can therefore be attributed to

labour and management, since they can be expected

to work out arrangements that will be mutually

acceptable to them. Thus, the state stands to benefit

from orderly resolution of conflicts through

collective

labour

management

relations.

Furthermore, the following additional advantages

accrue directly to the state:

1.

the avoidance of the negative effects of

visible expression of conflict;

2.

the avoidance of political instability which

overt expression of unresolved conflict can bring

about;

3.

the removal of the need for state

intervention which may be mutually perceived as

biased towards labour or management, and therefore

unsatisfactory, and

4.

less efforts and resources of the state will be

expended by the state in attempting to help labour

and management resolve their differences.

Conditions Necessary For Effective Bargaining

The functions of collective bargaining can

only be realized if and only if the bargaining takes

place, and effectively if at all. Some of the factors

affecting the effectiveness of employers and

employees strategies have been on mutual trust. This

concept views collective bargaining as a system of

industrial management to the extent that trade unions

join employers in reaching decisions on matters in

which both parties have vital interests. Additionally,

the International Labour Organisation (ILO) (1974)

has itemized a list of prerequisites for effective

bargaining.

These factors and more are the following:

• favourable political climate.

• freedom of association.

•

power relationship between the management

and

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

49

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

labour.

•

Joint authorship of rule.

•

Stability of workers organizations.

•

Recognition of trade unions.

•

Willingness of the parties to give and take

•

Avoidance of unfair labor practices on the part

of both parties.

•

Ability of the parties to negotiate skillfully.

•

Willingness to negotiate in good faith and

reach agreement, and

•

Willingness to observe the collective

agreements that emerge.

Collective Bargaining in the Private Sector

It has been suggested that the Validity of

collective bargaining depends upon two critical

assumptions, namely that those who practice it believe

in a democratic way of life, and that there is a balance

of power between employers and employees. (Ubeku,

1983; Imoisili, 1984).

Generally, industrialization in Nigeria grew

rapidly in the 1970s but the contribution of the

industrial sector to employment growth has been

disappointing. Sectoral distribution of employment

(Table 1) shows that agriculture, distribution and

manufacturing continue to dominate total employment

in Nigeria with average shares of 58, i 6 and 10 per

cent respectively.

An important condition for the viability of

collective bargaining is the balance of power between

employers and employees. There are also legal

provisions which recognize the need for employers and

employees to exhaust all internal means of resolving

differences before resorting to third intervention. Law

also serves the role of providing standards (floor and/or

ceilings) for negotiating employers and employees;

examples are the Minimum Wage Act, 1981 and the

annual PPIB (Productivity, Prices and Incomes Board)

Guidelines which derive legality from the PPIB

Decree, No. 30 of 1977.

Volume 1 Numbe 2

July, 2008

A typical procedural agreement contains on

the following items:

1.

citation, recognition and scope.

2.

constitution of the National Joint Industrial

Council for the industry.

3.

grievance procedure (individual and collective

grievances.

4.

amendments procedure.

5.

appendices.

In Nigeria, the law recognises industrial

employers' association,

senior staff associations

junior staff unions as trade unions. In addition,

employers are enjoined to grant automatic recognition

(for purpose of collective bargaining) to the other, two.

unions (that i senior staff association and junior staff

union).

Collective Bargaining Strategies

A behavioural theory of negotiations suggests

that there are four components of collective bargaining.

These are distributive (in which economic issues are

divided), integrative bargaining (in which joint

problem-solving takes place), attitudinal structuring (in

which the perceptions of the opposition are

manipulated), and intra organizational members are

changed.

In most negotiations there are distinct

strategies either the union or management can employ each with its own function for the interacting parties,

its own internal logic, and its own identifiable sets of

instrumental acts or tactics. The strategies are:

1.

Distributive Bargaining: This is a

competitive, confrontational, win-lose strategy.

Distributive bargaining occurs when one party wants to

achieve some contract provision that the other side is

opposed to. It refers to those activities instrumental to

the attainment of one party's goals when they are in

basic conflict with those of the other party. The

function is to solve pure conflict of interests. Goal

conflict can be based around

bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

50

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

allocation of resources. The process is not solely

concerned with economic conflict, it may also relate to

power or status problem. Viewed in terms of game theory,

distributive bargaining is a fixed sum game in which one

party's gain is a loss to the other party.

2.

Integrative Bargaining: This is a cooperative

strategy in which a common goal is the focus of attention.

Integrative bargaining occurs when both the management

and the union must work together to solve a mutual

problem. It therefore refers to those activities

instrumental to the attainment of objectives which are not

in fundamental conflict between the parties. By the nature

of the problem, it permits a solution that benefits both

parties or, at least, the gains of one side do not represent

equal sacrifices by the other.. In game theory terms, we

are faced with a variable sum game in which each party

gains a bit.' For instance, to stay, competitive and secure

jobs, both sides may agree to relax some work rules and

permit automation of production operations.

While

some workers are trained on the new equipment those

displaced by the technological improvements are to be

retrained to fill labour shortages elsewhere in the

production process.

Sometimes integrative bargaining is referred to

as concessionary bargaining. Under difficult economic

conditions, management may ask for concessions or

"give-backs" from organized labour, in return, as' it

should be expected, management will also reciprocate by

granting some valuable concessions to-the employees.

3.

Attitude Bargaining:

Attitudinal structuring

focuses on the function of negotiation which is concerned

with influencing the relationship between the parties.

Attitudes may range from friendliness to hostility,

competitiveness,

cooperation, trust; or respect.

Certainly,

existing

relationships would have been

influenced by such factors as technology, market, basic

ideology, the state of the economy, etc. nevertheless,

negotiators often seek to produce attitudinal change

during their interactions. Attitudinal structuring is

Volume 1 Number 2

July, 2008

concerned with those activities that are instrumental to the

attainment of desired relationship patterns between the

parties. Unlike distributive and integrative bargaining

which are joint decision processes, attitudinal structuring

represents a socio-emotional, interpersonal process.

4.

Intra-Organisational Bargaining: This has to

do with the activities taking place within the parties and

not between them. It is concerned with consensus seeking behaviour, that is, those activities that structure

the relationship between negotiators and those they

represent. Negotiators respond to demand from their own

organizations and from across the bargaining table. Both

aspirations about issues and expectations about behaviour

may vary widely. The process tends to be more crucial

within unions than within management and it is certainly

much more visible within the unions. In short, intraorganisational bargaining provides one of the most

effective tests of the level of organization attained by

unions.

Conclusion and Policy Option

Collective bargaining is a powerful method by

which joint determination of terms and conditions of

employment are arrived at between employers and

employees. Thus an attempt has been made in this paper

to examine the concept of collective bargaining,

employment distribution in Nigeria with reference to its

nature, the key principles, the scope and basic strategies.

The outcome of collective bargaining (if

successful) is a collective agreement which should

become a contract to be administered and interpreted from

day-to-day; hence collective agreement appears to be the

product of a resolved conflict.

In Nigeria, the reports of various committees on

conditions of service especially that of public employees

were determined largely through government legislation.

Collective bargaining can thrive very well in a democratic

environment but the unfortunate thing with

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

51

Adamawa State University Journal of Decision Analysis

Volume I Numbe 2

Nigeria Labour Unions is that Nigeria has witnessed

more military rule than democratic rule rendering

collective bargaining inactive. The present democratic

administration is no exemption. For example, in the

Nigerian public sector, the lack of good faith

negotiation is to be explained by the limited authority

of the civil servants who represent government on the

bargaining table. Our policy makers should take special

note of this and make necessary adjustment.

Overall, collective bargaining offers both an

opportunity and a challenge especially to union leaders

and spokespersons. It is an opportunity because it seeks

to actualize the notion of industrial democracy and a

challenge because modern negotiation is more

dependent on the quantity and quality of information

than on boldface militancy. Neither management or

union, is able to unilaterally impose its will on the

other; both must seek mutual accommodation.

References

Armstrong, M. (1999). An Handbook of Human

Resource Management Practice". London:

Kogan Page Publishers. Adeoti, J. A. (2000).

"Collective Bargaining: Principles, Scope and

Strategies". An unpublished Article and

Lecture Note. Mimeograph.

Bierstecker, T. J. (1987). Multinationals, the State and

July, 2008

Control of the Nigerian Economy, New Jersey:

Princeton University Press.

DeCenzo, D. A. and Robbins, S. P. (1996). Human

Resource Management. New York: John

Wiley and Sons, inc.

Fajana Sola (2000). "Industrial Relations in Nigeria:

Theory and Features" 2nd Edition, Lagos:

Panal Press Ltd. Flanders, Allan (1965).

Industrial Relations: What Is Wrong with the

System, London: Faber and Faber Ltd.

ILO (1974). Collective Bargaining. Geneva.

Imoisili, C. (1984). "Industrial Relations and Collective

Bargaining". Industrial No. l.P-7.

Marginson, P.. and Sisson, K. (1990). Single Table

Talk Personnel Management. May, pp. 46-49.

Morawetz, D. (1974). "Employment Implications

of Industrialisation

in

Developing

Countries". Economic Journal, Vol. 84, pp.

491-542.

Omole, M. A. (1983). Collective Bargaining in

Nigeria: Fact or Fiction in Omole, M. A. L

(Ed.). Industrial Relations and the Nigerian

Economy. University of Ibadan. Department

of Adult Education.

Ubeku, A. K. (1983). Industrial Relations in

Developing Countries: The case of Nigeria.

London, Macmillan.

A bi-annual Publication of the Department of Business Administration, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria

52

![Labor Management Relations [Opens in New Window]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006750373_1-d299a6861c58d67d0e98709a44e4f857-300x300.png)