INTRODUCTION: The Nibelungenlied and its

advertisement

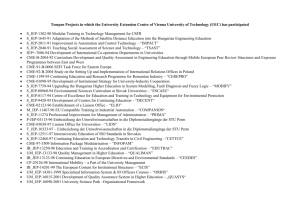

1 INTRODUCTION: The Nibelungenlied and its Homerian Context: Creating the Germany’s National Myth The exhibition is divided into eight thematic sections. The first is an introduction to texts that conditioned the reception of the Nibelungenlied, particularly treatises on poetic theory and earlier German translations of Greek and Roman epics. The second shows the transformation of European perspectives on Greek and Roman art and culture, which Johann Joachim Winckelmann set into motion and had a profound effect on the reception and depiction of the Nibelungenlied. The third section is devoted to 18th- and 19thcentury responses to the Nibelungenlied in the form of new editions, poetic interpretations, and early reviews. Illustrated editions and adaptations for the stage, both key components of the popularization of the Nibelungenlied over the course of the 19th century, make up the fourth and fifth sections, while 20th-century re-workings and English translations find a place in the sixth and seventh. The exhibition concludes with a digital facsimile of a medieval manuscript of the Nibelungenlied. THE CATALOGUE I. THEORETICAL AND POETIC INFLUENCES ON THE RECEPTION OF THE NIBELUNGENLIED 1. Martin Opitz. Buch von der Deutschen Poeterey. In welchem alle ihre eigenschafft und zuegehör gründtlich erzehlet / und mit exempeln außgeführet wird. Brieg: Bey Augustino Gründern. In Verlegung David Müllers Buchhandlers in Bretzlaw, 1624. The first and most prominent of the 17th-century theorists, Martin Opitz (1597-1639), led his contemporaries to the first flowering of German poetry in the modern era with his Buch von der Deutschen Poeterey (1624), in which he describes poetic technique and encourages Germans to write poetry themselves. It is noteworthy that Opitz treats Homer as one great poet among the many greats of ancient Greek and Rome, while Virgil is considered the greatest classical poet, a sentiment typical of the period. 2. Johann Christian Gottsched. Versuch einer critischen Dichtkunst vor die Deutschen: darinnen erstlich die allgemeinen Regeln der Poesie, hernach alle besondere Gattungen der Gedichte abgehandelt und mit Exempeln erläutert werden ... / Anstatt einer Einleitung ist Horatii Dichtkunst in deutsche Versse übersetzt, und mit anmerckungen erläutert von M. Joh. Christoph Gottsched. Leipzig: B.C. Breitkopf, 1730. This text made Gottsched’s name. In it, he emphasizes the eternal quality of literary standards, ignoring historical aspects of literature in favor of proscriptive formal and moral arguments as criteria of literary criticism. Gottsched believes the heroic epic to be the “true magnum opus of all poetry”:1 Homer is, as far as we know, the very first to attempt this type of work, and carried it out with such luck, or better, with such skill, that […] he is presented to all his successors as 1 “das rechte Hauptwerk und Meisterstück der ganzen Poesie” (Gottsched 1751, II.4 469). 2 the paradigm. […] Homer is therefore the father and the first inventor of this [type of] poem, and thus a truly great intellect, a man of special ability… 2 3. Johann Jakob Bodmer. Character der Teutschen Gedichte ... Zürich: 1734 [bound with Haller, A. von. Versuch schweizerischer Gedichten. Bern, 1732]. Early Modern German literary critics often complain that the German language itself makes writing poetry impossible; however, a young Bodmer (1698-1783) argues in this verse essay on the subject: “even Germans can vault themselves onto Mount Parnassus.”3 Some twenty years later, Bodmer would hold up the newly rediscovered Nibelungenlied as proof of this argument. 4. Simon Schnaidenreißer (trans). Odyssea, das seind die aller zierlichsten vnd lustigsten vier vnd zwaintzig Bücher ... Homeri, von der zehen järigen Irrfart ... Vlyssis ... / durch Meister Simon Schaidenreißer, genant Mineruium ... zü Teütsch transsferiert ... [Augsburg]: Alexander Weißenhorn, 1538. This is the first modern-language translation of the Odyssey. Thirty printings of Latin translations of the Odyssey and Iliad had been produced in German-speaking territories before it, and Schaidenreißer’s translation represents the Humanist push for the dissemination of ancient texts to an audience beyond traditional learned circles. Translators feared that the less educated could misunderstand or misuse classical thought, but obviously believed the benefits were great enough to attempt the undertaking. For these reasons, 16th-century translators took steps to ensure a ‘proper’ understanding of classical authors. Schaidenreißer (ca. 1500-1573) employs a contextualizing introduction and illustrations that highlight the most pedagogically useful content to make the story relevant to readers of Reformation-era Germany and to downplay morally ambiguous content. The size of the book and quality of the paper suggest a wealthy target audience, likely members of the rising merchant class. Weißenhorn printed two title pages for Odyssea (one reading 1537, the other 1538), but it seems that there was only a single print run (Weidling, xi-xii). 5. Ibid. Homeri des aller hoch berümbsten [!] und griechischen Poeten Odissea: ein schöne nützliche und lustige Beschreibung von dem Leben, Glück uñ Vnglück des dapffern klugen vnnd anschlegigen Helden Vlyssis ... / verdeutscht durch den ... Herrn M. Simon Mineruium ... sutzt auffs neu vbersehen und corrigiert. Gedruckt zu Franckfurt: [durch Johannem Schmidt: in Verlegung Hieronimi Feyerabends], 1570. This 2nd edition of Schaidenreißer’s Odyssea likely was unauthorized. The text has been abridged somewhat; the expensive large-format woodcuts replaced by smaller, less 2 Homer ist, so viel wir wissen, der allererste, der dergleichen Werk unternommen, und mit solchem Glücke, oder vielmehr mit solchem Geschicklichkeit ausgeführet hat […] und allen seinen Nachfolgern zum Muster vorgeleget wird. […] Homer ist also der Vater und der erste Erfinder dieses Gedichtes, und folglich ein recht großer Geist, ein Mann, von besonderer Fähigkeit gewesen […](Gottsched 1751, II.4 469). 3 “Auch Teutsche können sich auf den Parnassus schwingen” (Bodmer 1734). 3 detailed ones. The practical, diminutive size suggests the volume was not intended to become an ornamental or status-conferring possession for the newly wealthy, but made for reading. 6. Johann Spreng (trans). Ilias Homeri: das ist Homeri dess ... griechischen Poeten XXIIII. Bücher: von dem gewaltigen Krieg der Griechen wider die Troianer ... : Dessgleichen die 12. Bücher Æneidos dess ... lateinischen Poeten Publij Virgilij Maronis ... / in artliche Teutsche Reimen gebract von weilund Magistro Johann Sprengen, gewesenem Kays. Notario, Teutschen Poeten, vnd Burgern zu Augsburg. Gedruckt zu Augspurg: durch Christoff Mangen, In Verlegung Eliæ Willers, 1610. Each of Homer’s epics was translated into German only once from the advent of the printing press until the beginning of the 18th century, although both Schaidenreißer and Spreng’s translations went through multiple editions (two and five, respectively).4 Despite this, it took seventy years for the Iliad to join the Odyssey in German translation. The aim of Spreng’s translation is, like Schaidenreißer’s, to disseminate a venerable work to the widest possible audience. Published after the translator’s death, the book begins with a commemorative portrait and poem. In the poem, a colleague named Christoph Weinenmair praises Spreng as a great scholar and poet in his own right, while also lauding the Augsburg bureaucrat and Meistersinger’s use of his free time to translate the knowledge of the world into German: While of his station aware, He did occupy his time so spare With translating books to German, His Fatherland to emblazon…5 7. Christian Heinrich Postel (trans). Die listige Juno. Wie solche von dem grossen Homer, im vierzehenden Buche der Ilias abgebildet, Nachmals von dem Bischoff zu Thessalonich Eustachius ausgelaget, numehr in Teutschen Versen vorgestellet und mit Anmärckungen erklähret durch Christian Henrich Postel. Hamburg: Gedruckt und verlegt durch Nicolaus Spieringk, 1700. In 1700, Christian Heinrich Postel (1658-1705), a well-known opera librettist with a passion for philology, published an excerpt from the Iliad under the title Die Listige Juno (Cunning Juno). Postel employs an approach that seems quite modern in comparison to the translations by Schaidenreißer and Spreng – the translator includes the original Greek beside the German translation as well as exposition and criticism by himself and an ancient author. After the Homer fragment, an exegesis of the text by an ancient scholar appears, followed by Postel’s own interpretation. In place of the expository marginalia of the earlier translations, which mostly summarize the text, Postel employs footnotes to describe his sources very precisely. Interestingly, no knowledge of Greek or Latin is 4 Data are difficult to come by, but it appears that by the 16th century, editions reached between three and four thousand copies; smaller editions could of course be made, but at correspondingly higher prices (Hirsch 1974, 68). 5 “Inmittelst seines Ampts bedacht/ Hat er die ubrig zeit zu bracht/ Mit Bücher Teutsch zu transferieren/ Dardurch sein Vatterland to zieren/…” (Spreng 1610, n.p.). 4 necessary to read Postel, because every quotation is translated; this suggests that Postel, too, was aiming for an audience who may have been closer to monolingual than trilingual. On the other hand, the use of German no longer had to suggest a less educated audience; over the course of the 17th century, the movement toward the vernacular as an acceptable language for learned texts had grown tremendously. Like Opitz and Bodmer, Postel is quick to refute the idea that German is inferior to other languages: in the introduction he writes, “our noble German language is just as suitable to that for which the other European languages are used”6 and therefore able to produce as elegant a translation of Homer as had been made in English and French. Postel’s Cunning Juno is representative of the ascendance of Homer in German thought; always a great figure, Homer’s shadow came to envelop other ancient poets. Postel himself considers Homer incomparably great: he is the most beautiful and also the most effortless of all Greek poets; the great and immortal Homer, of whom ancient and modern scholars rightly believed that the treasure of all knowledge and human science lies hidden within him. 7 In addition, Postel pointedly attacks previous translations of Homer into German, which serves to highlight the radically changing norms of translation over the course of the Early Modern Period. Given the small number of Early Modern translations, it must be assumed that he includes at least Spreng's Iliad, if not Schaidenreißer's Odyssea in this complaint. II. PERCEPTIONS OF ANTIQUITY AFTER WINCKELMANN 8. Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst. Dresden und Leipzig: Im Verlag der Waltherischen Handlung, 1756. As modern scientific methods developed during the Enlightenment, so did archaeology, making a more accurate understanding of ancient Greece possible. Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) was the first and most influential of early archaeologists and a pioneer in the field of art history. He considered the aesthetics of ancient Greece to be the absolute and timeless standard of beauty, a point of view that soon became dominant in German-speaking lands. 9. Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks. [“With Instructions for the Connoisseur, and an Essay on Grace in Works of Art. Translated from the German Original of the Abbé Winckelmann, Librarian of the Vatican, F.R.S. &c. &c. Henry Fusseli, A. M.”] London: Printed for the Translator, and Sold by A. Millar, in the Strand, 1765. “unsere edele Teutsche Sprache [ist] eben da zu geschickt / wo zu die andern Europäischen Sprachen gebrauchet warden” (Postel 1700, n.p). 7 “er sei der schönste und dabei der leichteste aller Greichischen Poeten; de[r] gross[e] und unsterblich[e] Homerus / von dem mit recht die Gelahrten alter und neuer Zeiten schon gehalten / daß der Schatz aller Weißheit und menschlicher Wissenschafft in ihm verborgen lege” (Postel 1700, n. p.). 6 5 The Swiss-born British painter Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), also known as Henry Fuseli, was a friend and student of Bodmer and translated Winckelmann’s best-known work into English. Füssli also was greatly interested in the Nibelungenlied and created a number of paintings and drawings based on the epic, but which did not make their way into print during Füssli's lifetime. Many of these artworks are held in the Kunsthaus in Zürich. 10. Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Abbildungen zu Johann Winckelmanns sämtlichen Werken. Donauöschingen: bei J. Velten, 1835. Winckelmann’s espousal of Grecian aesthetics cemented the high estimation of ancient Greek art in Germany. To him, it embodied “noble Simplicity [and] silent Greatness;” a mindset that influenced 19th-century painters so strongly that artists began to illustrate the medieval German poem in the style of ancient Greece. 11. Johann Heinrich Voß (trans). Homers Odüßee. Wien: [publisher unknown], 1789. Over the course of the 18th century, and certainly after Winckelmann’s prodigious contributions to the study of ancient Greece, the conceptualization and illustration of Homer’s epics more accurately reflected the original composition and content of the poems. The poet Johann Heinrich Voß (1751-1826) translated the Odyssey (1781) and the Iliad with astounding fidelity to the original, using dactylic-spondaic hexameter with very few trochees. Voß’s translations are still greatly admired today. 12. Johann Heinrich Voß (trans). Homers Odysee. [“Mit 40 Original-Compositionen von Friedrich Preller.”] Leipzig: Verlag von Alphons Dürr, 1877 (3rd ed). In this volume we can see how Winckelmann’s celebration of Greek aesthetics influenced the illustration of Homer’s works. III. THE NIBELUNGENLIED AFTER ITS REDISCOVERY 13. Johann Jakob Bodmer. “[Zürich. Wir zählen gegen dreyzig verschiedene Helden=Gedichte…].” In: Freymüthige Nachrichten von neuen Büchern, und andern zur Gelehrtheit gehörigen Sachen. 13.12 (“Mittwochs, am 24. Merz, 1756”): 92-94. News of the rediscovery of the Nibelungenlied first reached the public in the modest format of this journal article from 1756. Bodmer writes, a year ago, I had the pleasure of discovering such [a manuscript], which seemed more worthy than others to be torn from the obscurity of its fate. The latter half is so conceived that it seems to be quite a regular work, even in the sense of plan and composition. The content is no less warlike than Homer’s Iliad; we have heroes of various character, of various kinds of valor …8 “Ich hatte vorm Jahre des Vergnügen ein solches zu entdecken, weches mir vor andern würdig scheint, daß mit dem Untergange, dem es zuteilt, sollte entrissen werden. Die hintere Häfte ist so 8 6 Despite Bodmer’s implications, he did not discover the manuscript of the Nibelungenlied himself; a medieval manuscript version (known today as MS C) was sent to him by a Swiss doctor, Jakob Hermann Obereit (1725-1798), who stumbled across it in the ducal library of Hohenems in Voralberg, Austria. Bodmer and his colleague Johann Jakob Breitinger did, however, work energetically to convince academics and the general public of the Nibelungenlied’s importance. In the following years, the Freymüthige Nachrichten published many such articles by Bodmer concerning the Nibelungenlied. 14 Johann Jakob Bodmer. Chriemhilden Rache, und die Klage; zwey Heldengedichte aus dem schvvæbischen Zeitpuncte. Sammt Fragmenten aus dem Gedichte von den Nibelungen und aus dem Josaphat. Darzu kœmmt ein glossarium. Zyrich: Verlegen Orell und comp., 1757. Chriemhilden Rache or Chriemhild’s Revenge is the first printing of any part of the Nibelungenlied. Bodmer trimmed the story drastically when he prepared the long epic for publication, causing the Nibelungenlied to read more like a biography. Although Bodmer does his best to legitimate the plot structure of the Nibelungenlied, it is clear that he finds it inferior in comparison to Homer’s epics. In the introduction to Chriemhild’s Revenge, Bodmer makes excuses for what he considers flaws and justifies the substantial cuts he makes to the text by comparing his own work to Homer’s: I cut all these parts, and I think with the same authority with which Homer left out the kidnapping of Helen, the sacrifice of Iphigenia and all the happenings of the ten years before the dispute between Achilles and Agamemnon, of which he only mentions familiar aspects as the occasion arises.9 Bodmer also goes to great lengths to show similarities between the style of the Nibelungenlied and Homer’s epics. He wishes his discovery could become the great national, even universal, epic, but like Opitz and Gottsched, Bodmer does not trust the competence of Germanic poets, judging them only in relation to Homer’s epics rather than on their own terms. 15. Johann Jakob Bodmer. “Die Rache der Schwester.” In: Calliope (v 2). Zürich: bey Orell, Geßner und Compagnie, 1767. 309-372. In the years following the discovery of the Nibelungenlied, Bodmer did his best to attract readers to the poem. This longer poem, entitled “The Sister’s Revenge,” is a rewriting of the latter half of the epic in hexameter. In it, Bodmer again attempts to create a more Homeric text. beschaffen, daß sie für sich allein ein ziemlich regelmäßiges Werk ausmachet, selbst in Absicht auf den Plan und die Einrichtung. Der Innhalt ist nicht weniger kriegerisch als Homers Ilias, wir haben da Helden von verschiedenen Charakter, von verschiedener Art der Dapferkeit…” (92). 9 “Alle diese Stüke habe ich abgeschnitten, und ich glaube mit demselben Rechte, mit welchem Homer die Entführung der Helena, die Aufopferung der Iphigenia, und alle Begegnisse der zehn Jahre, die vor dem Zwiste zwischen Achilles und Agamemnon vorgergegangen sind, weglassen hat, auf die er nur bey Gelegenheiten sich als auf bekannte Sachen beziehet” (Bodmer 1757, vii). 7 16. Gerhard Anton Gramberg. “Etwas vom Nibelungen Liede” In: Deutsches Museum. 2. 1783, 49-73. Leipzig, Weygand, 1783. Gramberg dismisses Bodmer’s use of hexameter in “The Sister’s Revenge” as “inappropriate” [“nicht angemessen”]. For his own “Verjüngung” or “rejuvenation” of a few quatrains of the Nibelungenlied, Gramberg uses the ballad form (abab). The aural effect is less ‘Grecian’ than Bodmer’s adaptation and thus considered more ‘Germanic’ by Gramberg. Nonetheless, it does not replicate the sounds of the original rhyme scheme (aabb). [Online exhibition only.] 17. Johannes von Müller. “Der Nibelungenlied” In: Sämmtliche Werke, vol. 26 [Historische Kritik]. Ed. Johann Georg Müller. Stuttgart und Tübingen: J.G. Cotta, 1834 [1st pub. 1783 in Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen]. 36-40. The comparison of the Nibelungenlied to ancient Grecian epic touched on in the introduction to Chriemhilden Rache is integral to its reception history. In 1783, the wellknown 18th-century Swiss historian Johannes von Müller (1752-1809) commented on “diese[s?] vortreffliche Gedicht, auf welches die Nation stolz thun darf.”10 In this short essay, von Müller, whom Körner calls the “erste einsichtsvolle Stimme” to comment on the epic,11 draws attention to particular similarities between the Nibelungenlied and the Iliad: the age of composition is distinct from that in which the story takes place in both poems, the time separating composition from the historical acts described is approximately the same and that “in both poems there are more great passions than great men, greater heroes than kings, and portrayals of accidents that could leave no human soul unmoved.”12 Despite honest praise, von Müller considers the Nibelungenlied deeply inferior to the Iliad: This is not the place to describe in detail how and why the Greek is so far above the German as Jupiter, whose eyebrows’ motion shake the heavens, is above the dwarf Alberich; but we may be assured, that, if the Nibelungenlied is revised (not too much, but rather without harming its antique form), our nation too will be able to prove to what degree Nature succeeded in the North.13 Müller, Johannes von. “Der Nibelungenlied” In: Sämmtliche Werke, vOL. 26 [Historische Kritik]. Ed. Johann Georg Müller. Stuttgart und Tübingen : J.G. Cotta, 1834 [1st pub. 1783 in Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen]. 37. 11 Körner 1911, 12. 12 “In beiden Gedichten sind mehr große Leidenschaften als große Menschen, größere Helden als Könige, und Gemälde von Unfällen, welche keine menschliche Seele kalt lassen können” (Müller 1783/1834, 40). 13 “Es ist hier der Ort nicht, ausführlich darzuthun, worin und warum der Grieche so hoch über den Deutschen ist, als der Jupiter, dessen Augenbrauendurch ihre Bewegung den Himmel erschüttern, über den Zwerg Alberich; aber das düren wir versichern, daß, wenn der Nibelungen Lied nach Verdienst bearbeitet wird (nicht aber zu sehr, sondern seiner antiken Gestalt ohne Schaden), auch unsere Nation eine Probe wird aufstellen dürfen, wie weit es die Natur im Norden zu bringen vermochte” (Müller 1783/1834; compare to Wyss 1990 or Ehrismann 2002). 10 8 Von Müller’s most famous pronouncement on the Nibelungenlied is that it “could become the German Iliad,” but that it “will never become as widely known as it deserves, if scholarly hands do not give it the help, which Homer received from those who first made him the favorite book of all Greeks.”14 Whatever one thinks of the Iliad-comparison, Müller was the first to attempt a historical reading of the Nibelungenlied. In it, he was the first to recognize Attila the Hun as Etzel. As for its author, the Swiss historian suggested a Swiss aristocrat, Eschenbach von Uspunnen. Although Müller’s commentary on the Nibelungenlied did not awake interest in the epic immediately, it was of the same importance for the reception of the Nibelungenlied as Lessing’s Seventeenth Literary Epistle for the reception of Shakespeare in Germany (Körner 1911, 12). [Online exhibition only.] 18. A. W. Schlegel. “Aus einer noch ungedruckten historischen Untersuchung über das Lied der Nibelungen.” In: Deutsches Museum (v1); Friedrich Schlegel (ed.). Wien: In der Camesinaschen Buchhandlung, 1812. 9-36. In the 19th century, evaluation of the Nibelungenlied underwent a significant change, but one that remained intimately connected to the relationship of German literature to foreign literatures. German literary criticism became markedly politicized during the years leading up to the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon (1813-1814) – desire for a national epic took on a new urgency after the fall of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and French occupation (Schulte-Wülwer 1980, 30). Comparisons to the Iliad were still omnipresent, but the Iliad was losing ground. The Schlegel brothers at the center of the German Romantic movement (and representative of this new approach to the Nibelungenlied) were both interested in the epic as part of a medieval literature that would unify German culturally and politically (Frembs 2001, 18). In this article, August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767-1845) comments with dismay on the difficulty of popularizing the Nibelungenlied: It is unbelievable how much must be done before a poetic transmission [Überlieferung], once known everywhere but now the long-forgotten lore of Antiquity, is brought into circulation again and breaks through to make a universal and vital impact, after one has picked it out of the dust and mildew of old parchment… 15 19. E. Julius Leichtlen. “Neuaufgefundenes Bruchstück des Nibelungenliedes aus dem XIII. Jahrhundert. Mit Bemerkungen über die Gesangsweise und die geschichtlichen Personen des Liedes.” In: Forschungen in Gebiet der Geschichte, Alterthums und Schriftenkunde Deutschlands. Freiburg im Breisgau: Franz Xaver Wangler, Wagner’sche Buchhandlung, 1820 (Bd. 1, Hft. 2). Courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library. Das Nibelungenlied “wird nie so allgemein bekannt werden, als es verdient, wenn ihm nicht gelehrte Hände den Dienst leisten, welchen Homer von denen empfing, die ihn zuerst allen Griechen zum Lieblingsbuch machten“ (Müller 1783/1834, 37; see Wyss 1990, 158). 15 “Es ist unglaublich, wie viel dazu gehört, ehe eine dichterische Ueberlieferung, eine vormahls allverbreitete aber längst verschollene Kunde der Vorzeit, nachdem man sie aus dem Staube und Moder alter Pergamente hervor sucht, wiederum in Umlauf gebracht wird, und bis zu einer allgemeinen und lebendigen Wirkung hindurchdringt” (9). 14 9 Following Johannes von Müller’s lead, much of the early critical work on the Nibelungenlied focused on drawing connections between the poem and historical figures and events. This chart outlines the familial relationships of characters from the epic. 20. Karl Lachmann. Der Nibelunge Not, mit der Klage : in der ältesten Gestalt mit den Abweichungen der gemeinen Lesart. Berlin: G. Reimer, 1826. Karl Lachmann (1793-1851) was the most prominent Nibelungen-scholar of the 19th century and began his work on the Nibelungenlied with his Habilitationsschrift (Berlin, 1816), “Über die ursprüngliche Gestalt des Gedichts von der Nibelungen Noth“ (“On the original form of the poem on the Downfall of the Nibelungs”). Lachmann’s 1826 and subsequent editions of the Nibelungenlied served as the standard for much of the 19th century. Lachmann based his edition on manuscript A, which he felt was closest to a lost original version made up of individual songs (“lays” or Lieder) pieced together, due to its relative roughness of form (Gentry 2002, 210). This theory of composition was adapted by Lachmann from his mentor Friedrich August Wolf’s theories about the structure of Homer’s epics. In addition, he developed the “Lachmann Method,” the descendant of which, stemmatics, is still used to understand the relationships of manuscripts editions of a text. Although Lachmann’s hypothesis about the origin of the Nibelungenlied was eventually discredited, he was instrumental in applying classical philology to later literatures, an important step in the development of modern literary studies (see Timpano 2005). This is Lachmann’s corrected and annotated personal copy of the first edition, which was acquired by the Beinecke in 2008. (An interesting side note: Lachmann assigned the signatures A, B and C to the surviving complete manuscript versions of the Nibelungenlied.) 21. Anastasius Grün. Nibelungen im Frack. Ein Gedicht von Anastasius Grün [pseud.=Auersperg, Anton Alexander Graf von]. Leipzig: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung, 1843. The Austrian earl Anton Alexander Graf von Auersperg (1806-1876) was a popular liberal author of politically motivated poetry. The mock epic, Nibelungs in Tailcoats, is an example of Auersperg’s brand of social critique couched in humor. 22. Ludwig Laistner (ed). Das Nibelungenlied nach der Hohenems=Münchener Handschrift (A) in phototypischer Nachbildung nebst Proben der Handschriften B und C. Mit einer Einleitung von Ludwig Laistner. München: Verlagsanstalt für Kunst und Wissenschaft vormals Friedrich Bruckmann, 1886 (=1; Berühmte Handschriften des Mittelalters in phototypischer Nachbildung). Although popular renderings of the Nibelungenlied remained influenced by German reception of Homer’s epics, critical work began to tend toward a reading of Nibelungenlied within its medieval context over the course of the 19th century. To my knowledge, Laistner’s edition is the earliest photo-facsimile edition of a Nibelungenlied manuscript. 1 0 IV. THE ILLUSTRATED EDITIONS OF THE 19TH CENTURY 23. Joseph von Laßberg (ed). Der Nibelunge Lied. Abdruck der Handschrift des Freiherrn Joseph von Laßberg. [Mit Holzschnitten nach Originalzeichnungen von Eduard Bendemann und Julius Hübner.] Leipzig: Otto und Georg Wigand, 1840. The ‘improvement’ of the Nibelungenlied took many forms, including changes to the text itself and Grecian-influenced illustration. At the same time, the historical context of the Nibelungenlied was communicated solely though the illustrations; such editions did not contain introductions or appendices with background information. The illustrators of this edition were Eduard Bendemann (1811-89) and Julius Hübner (1806-82), members of the Düsseldorf School, which was known for Christian scenes in the Romantic style. Close friends and brothers-in-law, Bendemann and Hübner painted monumental historical and allegorical murals in palaces, churches, universities, and governmental buildings. 24. Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen (ed). Der Nibelungen Lied in der alten vollendeten Gestalt. Illustr. L.W. Gubitz [“nach Zeichnungen von Holbein”]. Berlin: VereinsBuchhandlung, 1842. [Online exhibition only.] Against the backdrop of Romantic reevaluation of the Middle Ages and a new spirit of nationalism, Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen’s publication of Manuscript C in 1807 ignited interest in a way earlier editions had not. Von der Hagen described his illustrated edition of 1842 as an “inexpensive edition of the old heroic poem in the original language printed in the ancient style”16; in combination with Holbein-like illustrations, the volume represents a “regeneration” of the poem “suited for the people” [eine volksmäßige Erneuung desselben] (Hagen 1842, iii). In the introduction to the 1842 edition, von der Hagen describes contemporary artistic endeavors concerning the Nibelungenlied: The best new artists – Bendemann, Hübner, Schnorr, Neureuther – have endowed [the Nibelungenlied] with such figurative depictions that along with the early pages from Cornelius and Schnorr’s murals in the Royal Palace in Munich, we already have a handsome Nibelungen Gallery to show for ourselves.17 A student of A. W. Schlegel in Berlin, von der Hagen (1780-1856) had attended and been inspired by the famous lectures concerning the Nibelungenlied, and it was von der Hagen who first called the Nibelungenlied Germany’s national epic (Körner 1911, 71). At the same time, von der Hagen’s illustrated editions assimilated the Nibelungenlied into a haphazard pseudo-antiquity, as in all 19th-century illustrated editions. Von der Hagen was quite pleased with the spread of new representations of the Nibelungenlied, as he was interested primarily in its effect on the present. As Susanne “wohlfeile Ausgabe des alten Heldenliedes in der Ursprache mit der alterthümlichen Schrift gedruckt” (Hagen 1842, iii). 17 Mit solchen bildlichen Darstellungen haben es die besten neueren Künstler ausgestattet, Bendemann, Hübner, Schnorr, Neureuther: so daß wir, mit den früheren Blättern von Cornelius und Schnorrs Wandgemälden in[m?] Münchener Königsbau, schon eine ansehnliche Nibelungen=Galerie aufzuweisen haben (Hagen 1842, iii). 16 1 1 Frembs notes, von der Hagen’s pathetic concept of the Nibelungenlied acted as war propaganda, and it is precisely this "misinterpretation" that would haunt the Nibelungenlied in the 20th century (see Frembs 2001, 21). 25. Gustav Pfizer. Der Nibelungen Noth. [Illustriert mit Holzschnitten nach Zeichnungen von Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld und Eugen Neureuther.] Stuttgart und Tübingen: J. G. Cotta’scher Verlag, 1843. It has been claimed that no other literary work was so often illustrated in Germany as the Nibelungenlied in the early decades of the 19th century (Lankheit 1991, 197). Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794–1872) is the most famous illustrator of the Nibelungenlied and these illustrations have appeared in countless editions. 26. Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld. The Nibelungen-Saga as displayed in the fresco paintings of Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld in the Royal Palace at Munich. Photographed for His Majesty King Louis II. of Bavaria by Jos. Albert. Munich: J. Albert, [ca. 1880]. Courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library. Schnorr spent four decades decorating the walls of the Royal Palace in Munich with scenes from the Nibelungenlied. V. EARLY INTERPRETATIONS FOR THE STAGE 27. Dr. Ernst Raupach. Der Nibelungen-Hort. Tragödie in fünf Aufzügen mit einem Vorspiel. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1834. Courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library. One of the most influential theater directors of his time, Ernst Raupach (1784-1852) wrote the first Nibelungen drama, a very free interpretation of the Nibelungenlied, which ignores the mythological substance of the epic in favor of theatrical effects. The play was first performed in 1828. 28. Richard Wagner. Siegfrieds Tod. Autograph libretto (Dresden, 28 November 1848). 38 pp. From the Frederick R. Koch Collection. Wagner’s work on what would become the Ring Cycle (The Rhinegold, The Valkyrie, Siegfried, Twilight of the Gods) began with Siegfrieds Tod (The Death of Siegfried). Wagner originally planned only The Death of Siegfried, basing it primarily on the Nibelungenlied. After completing The Death of Siegfried, Wagner rethought the project and created the four-part Ring Cycle, placing The Death of Siegfried at the end of the cycle as Götterdämmerung (The Twighlight of the Gods). Wagner based The Valkyrie and Siegfried on the Volsunga Saga and created Rheingold by bringing together many elements from the Eddas.18 Wagner’s personal library contained at least five versions of the epic including a Lachmann edition (2nd ed, 1836), a Simrock translation (3rd ed, 18 Patrick McCreless was kind enough to share these observations with me in discussion (see Patrick McCreless’s Wagner's "Siegfried" : its drama, history, and music. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1982 for more). 1 2 1843) and Schnorr’s illustrated edition of 1843 (entry 24).19 This manuscript is the libretto of The Death of Siegfried in Wagner’s own hand. 29. “The original contract for the Ring der Niebelungen.” [With: English trans. in accompanying volume: "Translations. Letters and contract for the Ring..."] This contract, signed by Richard Wagner and imprinted with his seal in red wax, outlines terms for the first printing of the Ring cycle. 30. Richard Wagner. To Hans Richter. Autograph letter. June 13, 1876. Two months before the first performance of the entire Ring Cycle, Wagner wrote this warm letter about the production’s progress to the conductor, Hans Richter (1843-1916). 31. Max Brückner. Ring des Nibelungen von Richard Wagner. Dekorationsentwuerfe von Prof. Max Brueckner in Coburg. Zur Auffuehrung in Bayreuth im Jahre 1896. Max Brückner (1836-1919) was a prominent set designer renowned among his contemporaries for his realistic sets. Brückner published this portfolio of designs for the twentieth annual performance of the Ring Cycle in Bayreuth. 32. Friedrich Hebbel. Die Nibelungen. Ein deutsches Trauerspiel in drei Abtheilungen. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1862. The Nibelungen is arguably Friedrich Hebbel’s (1813-1863) greatest work. For this trilogy (Horned Siegfried, The Death of Siegfried, Kriemhild’s Revenge) the leading German Realist dramatist won the first Schiller Prize. VI. THE NIBELUNGENLIED IN THE 20TH CENTURY 33. Hermann Degering. Der Nibelungen not in der Simrockschen übersetzung nach dem versbestande der Hundeshagenschen handschrift bearbeitet und mit ihren bildern... Berlin: Volksverband der Bücherfreunde, Wegweiser Verlag, 1924. Hermann Degering reproduced the only surviving medieval illustrations of the Nibelungenlied in a format reminiscent of medieval manuscripts in this edition based on the translation of Karl Joseph Simrock (1802-1876). First published in 1827, Simrock’s translation went through countless editions, and is said to have done the most, of all translations, to popularize the Nibelungenlied. In this way, Degering brought early 20thcentury readers closer to the haptic experience of the original. 34. Friedrich Hebbel. Die Nibelungen [“Mit 44 Original-Radierungen von Alois Kolb.”]. Witkowski, Georg (ed). Leipzig, K.W. Hiersemann [1924]. 19 Many thanks to William Whobrey, who suggested the following information about the contents of Wagner’s library, which can be found in Elizabeth McGee’s Richard Wagner and the Nibelungs (1990), 25–37. 1 3 In the same year as Degering’s edition in the medieval spirit, a fascinating edition of Hebbel’s Die Nibelungen filled with darkly dramatic, expressionist lithographs was published. The illustrator was Alois Kolb (1875-1942), a professor of graphic design at the Grafische Akademie in Leipzig. 35. Thomas Mann. “Richard Wagner und der 'Ring des Nibelungen.'” Zurich: [1938?]. Despite his opposition to the National Socialist movement, whose members used Wagner’s operas to fascist ends, Thomas Mann (1875-1953) remained a lifelong admirer of Richard Wagner. This undated typescript copy of a speech given in Zürich on 10 November 1937 was collected for Essays of Three Decades (1947). Corrections are in the hand of Helen Lowe-Porter, Mann’s English translator. 36. Heiner Müller. Germania Tod in Berlin. Berlin: Rotbuch-Verlag, 1977 (=His Texte; 5 & Rotbuch; 176). [Paperbound. Author’s presentation inscription to A. Leslie Wilson.] The East German playwright Heiner Müller (1929-95) enjoyed great critical and commercial success during his lifetime. This play, made up of thirteen short scenes, reflects Müller’s preoccupation with German culture and history. In stark contrast to 19th-century attempts to build a national myth out of the Nibelungenlied, Müller depicts Nibelungen warriors mocking fallen German soldiers as effeminate weaklings and desecrating their corpses, before masturbating together and senselessly murdering one another. Finally, the scattered remains meld into a gigantic, gruesome monster. VII: THE ENGLISH NIBELUNGENLIED 37. Henry Weber. “Der Nibelungen Lied. The Song of Nibelungen.” In: Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, from the earlier Teutonic and Scandinavian Romances; being an Abstract of the Book of Heroes, and Nibelungen Lay; with translations of Metrical Tales, from the Old German, Danish, Swedish and Icelandic Languages; with Notes and Dissertations. Edinburgh: James Ballantyne & Co. for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, London, 1814. Courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library. It is believed that the Scottish poet and novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) translated or assisted in the translation of these verses from the Nibelungenlied. Whatever role Scott might have had, this is the first appearance of any part of the Nibelungenlied in English. 38. Jonathan Birch (ed). Das Nibelungen Lied or Lay of the Last Nibelungers. [Translated into English Verse after Professor Carl Lachmann’s Collated and Corrected Text.] Berlin: Published by Alexander Duncker, Bookseller to His Majesty the King of Prussia, 1848. This is the first English translation of the Nibelungenlied for which claims of completeness were made; however, the translator Jonathan Birch (1783–1847) based his work on the problematic Lachmann edition. 1 4 39. George Borrow. “Chrimehilt.” Autograph poem [n.d.]. George Borrow (1803-81) was an English linguist and popular 19th-century travel writer. This is his English verse translation of the first nineteen stanzas of the Nibelungenlied. Borrow follows the rhyme scheme of the original; each quatrain is made up of two rhyming couplets. 40. William Morris. The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs. [Colophon: With two pictures designed by Edward Burne-Jones and engraved by W.H. Hooper ... Sold by the trustees of the late William Morris at the Kelmscott Press]. Hammersmith: “Printed at the Kelmscott press, Upper Mall and finished on the 19th day of January, 1898.” Better known for his role in the Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris (1834-96) created translations of the Aeneid and Odyssey and a number of shorter Icelandic sagas. Morris based this epic in four chapters, perhaps his most ambitious writing, on the Volsunga saga. The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs was first published in 1877, and this volume is one of only six copies on vellum created at the famed Kelmscott Press shortly after Morris’s death. 41. Friedrich Hebbel. The Niebelungs. A Tragedy in Three Parts. H. Goldberger (trans). [with seven full-page illustrations by G. H. McCall.] London W.: A. Siegele, [1903?]. Courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library. An early English translation of Hebbel’s prize-winning play from 1862 with several fullpage illustrations. VIII. DIGITAL MEDIA 42. Die Sankt Galler Nibelungenhandschrift: Parzival, Nibelungenlied und Klage, Karl, Willehalm. CD-Rom. Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen und dem Basler Parzival-Projekt (ed). St. Gallen, 2005. In the physical exhibition at the Beinecke, an excellent representation of Manuscript B could be made available through the possibilities of digital media technologies. One of the three complete manuscripts remaining today, the manuscript is housed in the monastery of St. Gallen in Switzerland, bound with other medieval manuscripts (including Parzival) in Codex 857. The study of medieval literature has profited enormously from new technologies such as high-resolution digital photography, electronic data storage and online fora. A facsimile of C, the Hohenems manuscripts that started it all, is also available online through the Badische Landesbibliothek in Karlsruhe, where it presently resides.