Rodent Wars and Cultural Battles

advertisement

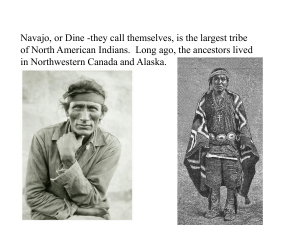

Rodent Wars and Cultural Battles: Reporting Hantavirus JOANN M. VALENTI Brigham Young University Media coverage of an outbreak of hantavirus in 1993 in the Four Corners region of the western United States and the resulting negative portrayal of Navajo culture reminds us that our relationship with indigenous peoples needs attention. The hantavirus case may suggest that reporting about environmental and health risks involving diverse cultures requires more than traditional journalism training provides. Although hantaviruses are distributed worldwide, when the emergence of a new strain of hantavirus in the United States reached the mass media agenda in 1993, charges of media stereotyping and environmental racism came in tandem. The initial storytelling was laden with negative images of a Native-American culture and erroneous generalities associating the disease with a particular people and their culture. Within weeks of the discovery of yet another strain of hantavirus, a National Public Radio (NPR) report (June 9, 1993) broadcast interviews with Navajo spokespersons, who already resented the insensitivity of journalists covering the story and linking the disease to the tribe. From the onset, Navajo spokespersons attempted to respond to what they saw as a crisis in the public sphere and correct misperceptions, as well as defend themselves in the face of ethnocentricism from both the media and health communities. Within one year, 40 people had died in 17 states. The disease was tagged as “an Indian ailment” only because the new viral strain had been first discovered on a Navajo reservation covering parts of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico. USA Today may have been first to use the tag “the Navajo flu,” although a representative from the National Center for Infectious Diseases (CID), a physician who authored the original formal notices announcing the new viral strain, claims a headline in the Albuquerque Tribune first used the label “Navajo Flu.” Albuquerque Tribune science reporter Lawrence Spohn equated that to calling AIDS “the gay disease.” The Arizona Republic used the label “the Navajo epidemic,” and the NBC News made reference to “the Navajo disease.” Dewayne Beyal, public information director for the Navajo nation, told one writer that while the spread of the disease might end, “the false image of Navajo life as impoverished and unsanitary may persist in the minds of many Americans.” The Navajo people were left to confront a host of hostile publics. Shortly after the outbreak, the University of Colorado and New Mexico State announced that Indian students would need a medical screening. Marshall Plummer, then vice president of the Navajo nation, responded, “Be assured that this illness is not Navajo-specific. The illness has struck non-Indians and people who live far away from Navajo lands. This is not a racial illness, but a regional one. I believe it behooves you as an educational institution to learn the known facts about this illness before resorting to actions that discriminate against our students.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) based in Atlanta, Georgia, became a key government source for the story, although CDC made an effort to refer media to state and local health departments. CDC press officer Bob Howard labeled the problem a “data dump,” referring to the estimated 25,000 annual media calls he receives. In hindsight, CDC spokespersons describe the case of the hantavirus outbreak as an example of “dueling amateurs,” a CDC investigator trained in epidemiology and a non-specialist reporter, rather than a case of cultural insensitivity. Even the scientific naming of the new hantavirus strain exacerbated the cultural problem. The first name proposed for the strain of hantavirus, Muerto Canyon virus (MCV), in use in the scientific literature, was derived from Canyon del Muerte (canyon of death), a site on the Navajo reservation. Traditionally, new viruses are named after where they are discovered. “The hantavirus was all over the United States,” Navajo National Council member Genevieve Jackson told an Associated Press reporter. “We resent the fact that it is named after a canyon here . . . CDC should have a little more respect and consideration for the Navajo people.” In response, CDC changed the name to Pulmonary Syndrome Hantavirus. The name finally accepted for the new strain, “Sin Nombre,” means “without a name.” Ongoing studies by state, federal and Indian groups indicate rodents throughout a number of states including much of the west, the northeast and the south carry the hantavirus disease. Continuing stories reported new cases of the disease. Follow-up coverage of the Four Corners story analyzed long-term economic woes created as fearful tourists cancelled plans to visit the area, and, in a related turn of events, the CDC announced a “war” on diseases, comparing “virulent cholera ravaging India” to “hantavirus killing Americans.” As would be expected in most major news stories, the majority of sources used were government representatives, although most journalists also sought out Navajo spokespersons. The president of the Navajo nation said at a press conference: “Navajos are finding themselves shunned in public places and business establishments. Navajos have been made to feel like plague bearers or lepers whose touch is to be feared.” Most national media editors and news directors relied heavily on wire services to report the story, recreating a fearful image of an entire region of the country and a culture. Micro Issues: 1. As the PR representative for the Tribal Council, what strategies or advice do you offer to council members? To the media? 2. As information official for the universities, how would you respond to this statement by Plummer and by media questions about your university’s actions? 3. A CNN report includes this statement: “An army of health care workers has descended on the U.S. Southwest. Its mission, to identify a mysterious illness that has killed 13 people, mostly Navajo Indians. The professionals have all the tools of modern medical investigation, but tribal traditions and taboos are complicating their probe.” Develop an effective communication strategy for (a) the Tribal Council, or (b) the State Health Department. Middle-range Issues: 1. A recent survey from the American Society of Newspaper Editors found minorities account for just over 10 percent of the total population of newsroom professionals. Native-Americans are the least represented at less than one half of 1 percent. Until these figures are more representative of the population, what training in cultural sensitivity could be built into our media processes to offer more promise of accurate and fair coverage to minorities? 2. When reporting on risk, media generally offer little or no information about the likelihood of its occurrence, often leaving an inaccurate public perception and unnecessary anxiety. Describe the ethics of communicating risk in a story such as the hantavirus outbreak. How could the risk of contracting the hantavirus have been placed in context? 3. ABC reported that Navajo children from Arizona were sent home after being told they could not visit with their pen pals at a Los Angeles school. The principal of the California school and her students were worried they might catch the disease from the Navajo children. Analyze the resulting PR crisis from the viewpoint of the Los Angeles school system that sent the children home. Macro Issues: 1. According to census data the Navajo have the highest proportion (48.8%) of members living in poverty of any Native-American tribe. What stereotypes of Native-Americans might have contributed to the reporting in the hantavirus story? 2. To help media accurately report on Indian issues and write articles involving tribal lifestyles, the Bureau of Indian Affairs encourages reporters to call for correct terminology or phrasing, and handbooks have been developed (see for example The American Indian and the Media). What role do the media play in perpetuating persistent racial bias? What role can media play in correcting persistent racial bias? 3. A Navajo reporter who spoke the Navajo language filed numerous stories on the virus. She said, “I have to put my Navajo-ness in the back seat and go on.” Discuss the pros and cons inherent in her position as a native Navajo and a reporter.