Mimickers of Bladder Neoplasia

advertisement

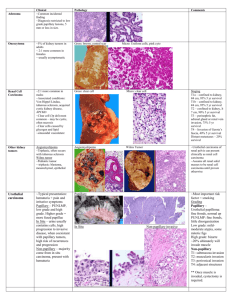

Mimickers of Bladder Neoplasia Jonathan I. Epstein, M.D. MIMICKERS OF ADENOCARCINOMA Cystitis Glandularis (Colonic Metaplasia) Occasionally, extensive cystitis glandularis is difficult to distinguish from adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder, as in the current case. Cystitis glandularis is a lesion of the urinary bladder that is thought to evolve either from von Brunn nests in the setting of chronic irritation and infection or in some cases as a congenital process reflecting partial origin of the bladder from the embryonal cloaca. Two distinct patterns exist. The typical form is composed of glands lined by cuboidal to columnar epithelium overlying layers of transitional epithelium. The second variant is termed cystitis glandularis, intestinal type, or colonic metaplasia. Colonic metaplasia is relatively uncommon and is characterized by glands lined with mucinous columnar epithelium (goblet cells) with basally located nuclei. Both may present clinically as large, exophytic masses, and histologically, colonic metaplasia may mimic well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Although there is overlap between colonic metaplasia and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in some of the histological features (dissecting mucin, infiltration of muscularis propria, atypia, and mitoses), the degree and extent of these findings differ between the two conditions. In contrast to the extensive mucinous pools seen in some adenocarcinomas, colonic metaplasia has only focal areas of mucin extravasation. Whereas adenocarcinomas typically show deep muscle invasion, the muscle invasion seen in colonic metaplasia tends to be more limited, although the case for this slide seminar is unusual in its extent of muscle invasion. Although rare adenocarcinomas may show bland cytology, most will have areas of the tumor with overt cytological atypia. The atypia seen in colonic metaplasia is not as severe and by itself would not be diagnostic of malignancy. Similarly, mitoses, although frequent in adenocarcinoma, are found only rarely in colonic metaplasia. Other cases of adenocarcinoma that are less differentiated show signet cells and necrosis, which are not found in colonic metaplasia. Endocervicosis A mimicker of adenocarcinoma of the bladder is endocervicosis. This lesion typically occurs in women in their 30s and 40s. Symptoms are those of either hematuria or those mimicking urinary tract infection. In addition to the bladder, this lesion may be seen in the uterine cervix and vagina. The lesion is composed of benign glands resembling endocervical glands that involve all layers of the bladder and occasionally the extravesicle tissue. In contrast to adenocarcinoma, there is no atypia, no mitotic figures, and no tissue reaction. Occasionally, there may be a suggestion of stroma surrounding the glands as seen in endometriosis. The lesion may grossly mimic cancer presenting as a mass lesion up to 5 cm. with occasional extravesicle involvement. Nephrogenic Adenoma (Nephrogenic Metaplasia) The other lesion that may mimic adenocarcinoma is nephrogenic metaplasia (nephrogenic adenoma). Nephrogenic metaplasias usually arise in the setting of prior urothelial injury, such as past surgery (60%), calculi (14%), or trauma (9%). Eight percent have a history of renal transplantation. Approximately twothirds of individuals affected with nephrogenic metaplasias are male, and in one-third the lesion is found when patients are less than 30 years of age. Nephrogenic metaplasias appear as papillary, polypoid, hyperplastic, fungating, friable, or velvety lesions. They are located throughout the bladder, though rarely found on the anterior wall. Eighty per cent are localized to the bladder, with 12% seen in the urethra and 8% in the ureter. Most nephrogenic metaplasias measure less than 1 cm., although they may attain dimensions as large as 7 cm. In eighteen percent of cases, multiple lesions are identified. Nephrogenic metaplasias have a broad histologic spectrum. A common pattern consists of tubules lined by low columnar to cuboidal epithelium. Nuclear atypia is virtually absent with mitoses either absent or rare. Nuclear atypia, when present, appears degenerative. Nuclei are enlarged and hyperchromatic, yet have a smudged indistinct chromatin pattern. These atypical nuclei often reside in cells with an endothelial or hobnail appearance lining vascular-like dilated tubules. Cystic tubules may contain colloid-like eosinophilic or basophilic secretions. Uncommonly, tubules are lined by either more columnar cells with pale cytoplasm or signet appearing cells; clear cells are rare and glycogen is usually absent. Nephrogenic metaplasias may also be papillary, usually lined by low cuboidal cells with scant cytoplasm or on occasion by oxyphilic cells. In contrast to adenocarcinoma, nephrogenic adenomas lack solid growth patterns, mitotic activity, prominent cytological atypia, and are not typically large deeply invasive tumors. Nephrogenic adenomas can focally involve the superficial aspects of the muscularis propria. Florid Cystitis Glandularis 1. Corica FA, Husmann DA, Churchill BM, et al: Intestinal metaplasia is not a strong risk factor for bladder cancer: Study of 53 cases with long-term follow up. Urology 50: 427-31,1997. 2. Jacobs LB, Brooks JD, Epstein JI. Differentiation of colonic metaplasia from adenocarcinoma of urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 28:1152-57,1997. 3. Young RH, Bostwick DG. Florid cystitis glandularis of intestinal type with mucin extravasation: a mimic of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 20:1462-68,1996. Endocervicosis 1. Clement PB, Young RH. Endocervicosis of the urinary bladder. A report of six cases of a benign müllerian lesion that may mimic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 16:533-42,1992. Nephrogenic Adenoma 1. Allen CH, Epstein JI. Nephrogenic adenoma of the prostatic urethra: a mimicker of prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 25: 802-808,2001. 2. Oliva E, Young RH. Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: A review of the microscopic appearance of 80 cases with emphasis on unusual features. Mod Pathol 8:722-730,1995. 3. Oliva E, Young RH. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra. A clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases. Mod Pathol 9:513-520,1996. 4. Young RH, Scully RE. Nephrogenic metaplasia: A report of 15 cases, review of the literature, and comparison with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urinary tract. Am J Surg Pathol 10:268-275,1986. POLYPOID CYSTITIS Polypoid cystitis may arise as a reaction to any inflammatory insult to the urinary mucosa. It occurs equally in males and females, with an age range of 20 months to 79 years old. Cystoscopically, it appears either as an area of friable mucosal irregularity or edematous broad papillae. Lesions usually are located adjacent to an inflammatory area. Lesions may be multifocal and can range up to 5 mm in size. As the urologist can more often recognize the inflammatory nature of the lesion compared to the pathologist, the pathologist should hesitate diagnosing urothelial carcinoma in case where the cystoscopic impression is that of an inflammatory lesion. In its most pronounced form, polypoid cystitis shows extensive submucosal edema with broad bulbous projections which have been termed bullous cystitis. Other cases of polypoid cystitis may be more difficult to distinguish from urothelial papillary carcinoma. While most examples of polypoid cystitis show edematous fibrovascular cores which are broad-based, isolated frond in polypoid cystitis can be narrownecked, thin, and delicate resembling the fibrovascular cores of papillary urothelial carcinoma. The fronds in polypoid cystitis uncommonly branch into smaller papilla as can be seen in papillary urothelial carcinoma. One must be careful in that out of context several papillary fronds within polypoid cystitis may closely resemble papillary urothelial carcinoma. However, one must assess the lesion in its entirety and, if overall, the lesion is that of polypoid cystitis, one should not over diagnose isolated papillary fronds as carcinoma. The urothelial mucosa overlying the edematous stalks may show reactive urothelial atypia and/or squamous metaplasia, and be accompanied by mitotic figures. Although the mucosa it typically of normal thickness, it may also be thickened mimicking a papillary urothelial tumor. Polypoid cystitis is a benign lesion without any risk of evolving into carcinoma. 1. Young RH. Papillary and polypoid cystitis: A report of 8 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 12:542-546, 1988. 2. Lane Z, Epstein JI. Polypoid/papillary cystitis: A series of 41 cases misdiagnosed as papillary urothelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol (in press) RADIATION-INDUCED PSEUDOCARCINOMATOUS HYPERPLASIA The first series to report this mimicker of invasive urothelial carcinoma was by Baker and Young in 2000 (2). Four cases were described, with follow-up available in one patient, which was benign. We have recently studied 20 cases with either radiation or chemotherapy induced pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia in the bladder; all 17 cases where follow-up information is available have had a benign clinical course. All patients presented with hematuria. 16 (80%) of the patients were male with an age range of 40 years to 85 years (median 69). The median interval from radiation to clinical presentation was 27 months. The longest interval in our study was 6.6 years and in the study by Baker and Young 8 years. The lesion consists of irregular nests of urothelium proliferating into the lamina propria. In addition to the architectural pattern mimicking cancer, most cases had prominent nucleoli, mild to moderate pleomorphism, and a few cases demonstrated mitotic figures. Key features to recognizing the nonneoplastic nature of this entity include the following features seen in the majority of cases: edema, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, inflammation, and most importantly fibrin deposits with in many cases the urothelial nests encircling the fibrin. The nests also do not extend irregularly down into the lamina propria or muscularis propria as is seen with the urothelial carcinoma. Seen in 50% of the cases were ulceration, epithelial vacuolization, and thick vessels, which are clues to the prior irradiation. This lesion may also less commonly be seen without a prior history of irradiation in patients with severe generalized ischemic disease or long-standing indwelling catheters. 1. Balker PM, Young RH. Radiation-induced pseudocarcinomatous proliferations of the urinary bladder: A report of 4 cases. Hum Pathol 2000; 31:678-683. 2. Chan TY, Epstein JI. Radiation or chemotherapy cystitis with “pseudocarcinomatous” features. Am J Surg Pathol (July); 28: 909-913, 2004. 3. Lane Z, Epstein JI. Pseudocarcinomatous epithelial hyperplasia in the bladder unassociated with prior irradiation or chemotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol 32:92-97, 2008. INVERTED PAPILLOMA Inverted papillomas commonly present with hematuria and/or obstruction (1). Eighty percent of patients are men usually 50-70 years old (range 9-94 years). Inverted papillomas have a polypoid appearance with a smooth or nodular surface. Less commonly, pedunculated lesions are seen. Most tumors arise around the trigone and bladder neck, with fewer cases situated in the prostatic urethra, renal pelvis, or ureter. Rarely, multifocal lesions have been described. Most inverted papillomas are less than 3 cm. though they may reach sizable proportions, as large as 7.5 cm. Inverted papillomas reveal at low magnification a surface which is usually smooth with underlying trabeculations of transitional epithelium. The nests may extend deep into the lamina propria yet muscle invasion is absent. The surface is typically composed of compressed urothelium without atypia. In areas transitional cell epithelium can be seen extending down from the surface as nests, anastomosing columns, or thin cords. At the edges of the nests or columns the cells often palisade perpendicular to the basement membrane with the inner layer of cells streaming parallel in a horizontal fashion, although this pattern need not be present. The cells may show non-keratinizing squamous metaplasia, but not keratin formation. The stroma is loose and delicate, without prominent inflammation, and surrounds the nests of solid epithelium. At most, there should be only slight atypia, with only scattered mitoses found towards the peripheral basal cell layer. Focally an otherwise typical inverted papilloma may show surface papillations or even papillary projections. These papillary projections when focal are still consistent with inverted papilloma. The papillary fronds in inverted papilloma often have the same growth of solid nests down into the stalk with peripheral palisading and streaming of the nuclei as seen in the sessile part of the lesion. Sometimes cyst or lumen formation may be seen within the transitional cell nests. Cysts are lined by flat to low columnar epithelium or flattened urothelial cells, and may contain mucinous material. Current studies have concluded that there is no relation between inverted papilloma and transitional cell neoplasia (3,4). 1. Witjes JA, Van Balken MR, Van de KAA CA. The prognostic value of a primary inverted papilloma of the urinary tract. J Urol 158:1500-1505, 1997. 2. Amin MB, Gomez JA, Young RH. Urothelial transitional cell carcinoma with endophytic growth patterns: A discussion of patterns of invasion and problems associated with assessment of invasion in 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 21:1057-1068, 1997. 3. Ho H, Chen YD, Tan PH, Wang M, Lau WK, Cheng C. Inverted papilloma of urinary bladder: is longterm cystoscopic surveillance needed? A single center's experience. Urology. 68:333-6, 2006. 4. Sung MT, Maclennan GT, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L. Natural history of urothelial inverted papilloma. Cancer 107:2622-7, 2006. NESTED VARIANT OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is a rarely encountered subtype of bladder carcinoma, with a prevalence of approximately 0.3% (1). According to one report, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma comprises less than one percent of invasive bladder carcinomas (2). In 1979, Stern observed a bladder lesion of closely packed epithelial nests closely resembling von Brunn nests. Although the nests appeared morphologically benign, the lesion recurred and may represent the first reported case of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma (3). Later, Talbert and Young described three bladder carcinomas with bland foci and features resembling von Brunn nests, nephrogenic adenoma, and inverted papilloma (4). In 1992, Murphy and Deana reported four cases of bladder carcinoma with nests of uniform cells that infiltrated the lamina propria. Each case showed aggressive or persistent disease, and the authors designated the entity “nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma” (5). More recently, studies have described additional cases of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma (6-11) as well as other examples of deceptively bland bladder carcinomas (12-14). Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is generally seen in older male patients who present with hematuria, although obstructive symptoms have been reported. To date, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma has been reported in only 4 women. At cystoscopy, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma has a widely variable appearance and has been described as a flat tumor, papillary tumor, a submucosal bump, indurated mucosa, or just slightly irregular or hemorrhagic mucosa. Reported tumor size has varied from 18 cm. While some early observations led to the conclusion that nested variant of urothelial carcinoma arises mostly at the trigone or ureteral orifices, additional reports have disputed this. We are aware of only two cases of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma in the ureter (5,7) although one other patient had apparent extension of a bladder nested variant of urothelial carcinoma into the ureter and kidney (1). Histologically, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is characterized by small, closely packed nests of epithelial cells infiltrating the lamina propria, at times anastomosing to form confluent nests. Accounts of cyst formation within the nests have been variable. Microcystic (7,1) and tubular (5,7) variants have been described, and large dilated cysts may be seen within tumor nests (2). Young has also reported a trabecular variant consisting of an irregular arrangement of anastomosing cords, as well as a variant with “spiked” nests, reminiscent of invasive squamous cell carcinoma (12). The nests may be surrounded by stroma that varies from dense and collagenous to loose and myxoid, or even edematous. A notable eosinophilic stromal infiltrate was observed in one study (12). The overlying urothelium may be normal in appearance. The diagnosis is most easily made by identifying muscle invasion. Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma has been reported in association with conventional urothelial carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and squamous carcinoma (1). Cytologically, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma may show very uniform, bland cells with only focal moderate atypia. Some have observed significant pleomorphism, particularly within regions of muscle invasion. Nucleoli may be prominent and mitoses may be seen, but are usually not numerous. Lymphatic invasion may be seen, although some authors have found it to be uncommon. In a study from our institution, immunohistochemical studies for MIB-1, p53, p27, and cytokeratin 20 showed some differences in staining but staining was highly variable and except for the occasional nested carcinoma with very high MIB-1 rates, our studies do not indicate that these tests will be routinely helpful in the differential diagnosis of florid proliferation of von Brunn nests and nested variant of urothelial carcinoma (11). Despite its innocuous appearance, the clinical course of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is generally aggressive. In a review of 24 cases, Drew et al. reported 55-60% of the tumors to show aggressive behavior, with mortality rates similar to high grade conventional urothelial carcinoma (7). The same study showed only 3/12 nested variant of urothelial carcinoma patients to be alive without disease at an average of 16 months follow-up. Few relatively indolent cases have been reported, including one patient who underwent radiation treatment and showed no recurrence at 72 months follow-up, one patient with apparently stable disease over a period of 8 years with nested variant of urothelial carcinoma in multiple consecutive biopsies, and one case in which the patient was treated only with TUR and BCG and has shown no recurrence over the ensuing 12 months (1,5,11). Confusion between benign urothelial proliferations and nested variant of urothelial carcinoma has led to delay in diagnosis and subsequent treatment (4). If muscularis propria is available, these entities may be more easily distinguished, although it has been our experience that even when muscularis propria invasion is present pathologists are hesitant to diagnose nested variant of urothelial cancer due to its bland cytology. In the setting of repeated negative urine cytology and negative transurethral biopsies, some cases have required open biopsy to make the diagnosis. In contrast to nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, examples of florid von Brunn nests in the bladder generally show larger nests with more regular shapes and regular spacing (11). Cystic formation is more pronounced in florid von Brunn nests, and involves a higher proportion of nest structures. Apical glandular differentiation and eosinophilic secretions are also more common. Atypia is absent, and the lesions have a flat non-infiltrative base. Cases of florid von Brunn nests in the ureter show small nests similar to nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Distinguishing features include in florid von Brunn nests a flat non-infiltrative base, a lobular or linear array of the nests, and a lack of cytologic atypia. The diagnosis of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma in the ureter or renal pelvis should also be made with caution in the absence of muscularis propria invasion, given the rarity of this variant of carcinoma at these sites and the recognition that florid von Brunn nests mimicking cancer has a predilection for the upper urinary tract. 1. Holmang S, Johansson SL. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: a rare neoplasm with poor prognosis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2001;35:102-105. 2. Billerey C, Marin L, Bittard H, et al. The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: report of five cases and review of literature. J Urol Pathol 1999;1:89-100. 3. Stern JB. Unusual benign bladder tumor of Brunn nest origin. Urology 1979;14:288-289. 4. Talbert ML, Young RH. Carcinomas of the urinary bladder with deceptively benign-appearing foci: a report of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:374. 5. Murphy WM, Deana DG. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: a neoplasm resembling proliferation of Brunn’s nests. Mod Pathol 1992;5:240-3. 6. Paik SS, Park MH. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Br J Urol 1996;78:793-794. 7. Drew PA, Furman J, Civantos F, Murphy WM. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: an aggressive neoplasm with innocuous histology. Mod Pathol 1996;9:989-994. 8. Ozdemir BH, Ozdemir OG, Sertcelik A. The nested variant of the transitional cell bladder carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol 2000;32:257-258. 9. Tatsura H, Ogawa K, Sakat T, Okamura T. A nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001;31:287-289. 10. Lin O, Cardillo M, Linkov I, Hutchinson B, Reuter VE. Immunohistochemical expression of p21, p27, p53, EGF-R, bcl-2 and MIB-1 in the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2002;15:170A. abstract. 11. Volmar KE, Chan TY, DeMarzo AM, Epstein JI. Florid von Brunn nests mimicking urothelial carcinoma: A Morphologic and immunohistochemical comparison to the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 1243-1252. 12. Young RH, Oliva E. Transitional cell carcinomas of the urinary bladder that may be under diagnosed: a report of four invasive cases exemplifying the homology between neoplastic and non-neoplastic transitional cell lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1448-1454. 13. Young RH, Zukerberg L. Microcystic transitional cell carcinomas of the urinary bladder: a report of four cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1991;96:635-639. 14. Amin MB, Gomez JA, Young RH. Urothelial transitional cell carcinoma with endophytic patterns. A discussion of patterns of invasion and problems associated with assessment of invasion in 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:1057-1068. Morphology of florid proliferation of von Brunn nests compared to nested variant of urothelial carcinoma Bladder Florid von Brunn Nests Ureter Florid von Brunn Nests Nested Variant of Urothelial Carcinoma Larger, more uniform nests with even spacing in some cases Small or mixed size crowded nests with linear or lobular arrangement Small crowded nests with variable shape and spacing Architecture Nests Cysts Large cysts, often involving 70-80% of nests Small cysts rare, involve less than 10% of nests Small cysts or clefts involving 20-30% of nests Cytology Atypia Significant atypia absent Significant atypia absent Common Uncommon Stroma Edematous, some with delicate concentric layering Variable, edematous stroma is unusual Dense and collagenous, less often edematous Muscle invasion Absent Absent Often present Apical differentiation At least focal moderate atypia noted in most Uncommon INFARCTS In between 20% to 25% of specimens removed for benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatic infarcts ranging in size from a few millimeters to 5 cm may be found. Patients with acute prostatic infarcts have prostate glands that are twice as large as those without infarcts. Also, patients with infarcts are more prone to acute urinary retention and gross hematuria than those without infarcts. These symptoms, however, may not be due to the infarcts but rather may be due to the larger size of the gland containing them, since the infarcts are often small and not close to the urethra. Acute prostatic infarcts are discrete lesions with a characteristic histologic zonation. The center of the infarct is characterized by acute coagulative necrosis and some recent hemorrhage. Immediately adjacent to the infarcted tissue, reactive epithelial nests with prominent nucleoli, some pleomorphism and even atypical mitotic figures can be seen. Progressing away from the center of the infarct, more mature squamous metaplasia is seen. Another finding seen within prostatic infarcts is squamous islands with central cystic formation containing cellular debris. Remote infarcts may also be recognized by finding local areas of densely fibrotic stroma admixed with small glands containing immature squamous metaplasia. Prostatic infarcts may rarely be sampled on needle biopsy, where it may be more difficult to appreciate the zonation (1). The key is recognizing the background hemorrhage, hemosderin deposition, and karryorhectic debris. If the infarct is not recognized, the reactive squamous metaplasia cases may be misdiagnosed as urothelial carcinoma. 1. Milord RA, Kahane H, Epstein JI. Infarct of the prostate gland: experience on needle biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1378-84.