Catch Up Pack: Foundation

advertisement

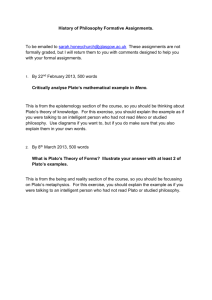

AS level Philosophy and Religion: Philosophy: Foundation Unit Point 1 – Plato - The analogy of the Cave The concept of Forms, especially the Form of the Good. The concept of body/soul distinction There are two Greek philosophers for you to study for the foundation exam, Plato and Aristotle. This pack will enable you to understand the basics of the initial work that the class has done on Plato, up until half term. You are probably starting lessons as the class begin to work on Aristotle. You must complete the tasks in the pack in order to continue in the class. This does not include everything that the class has done – it is selected as work for you to do at home so that you have a reasonable idea of where the class have got to. You will still need to do some work, catching up notes from other students on the course. There are two short essays set at the end of the pack. You need to make sure that you know how to approach essays for Philosophy and Religion, as you will be assessed by writing essays in exams at the end of the year. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................2 PLATO’S ANALOGY OF THE CAVE ....................................................3 THE CONCEPT OF THE FORMS ............................................................5 THE FORM OF THE GOOD ...................................................................10 THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN THE SOUL AND THE BODY .........14 1 BACKGROUND Strictly speaking, you do not need any background information on Plato – you just need to know about the set topics in his philosophy. However, it is very difficult to understand the topics with no background at all. You should read chapter 1 of Roy Jackson, Plato: a beginners guide. There are links to internet sites on Plato on the ‘Philosophy and Religion’ intranet pages, under links. It is important also to understand what Plato’s approach to philosophy is and how it relates to Aristotle’s approach, which you are currently studying in class. To do this read the text below and answer the questions: PLATO AND ARISTOTLE: HOW THEIR PHILOSOPHIES RELATE TO EACH OTHER Plato lived from 427-347 BCE. Plato was one of the first people to try to provide a full explanation of reality. He also set up the first university in the Western world – the Academy in Athens in Ancient Greece. People studied in the Academy and paid Plato, so he was a professional philosopher. Plato had a philosophy teacher called Socrates. Socrates taught him the method of questioning, by questioning him. The only thing we know about Socrates is what Plato wrote about him and the questions that Plato records Socrates asking. Therefore, Socrates is a mouthpiece for Plato’s ideas and some people even claim that Plato invented Socrates as a fictional character. Aristotle lived from 384-322 BCE. When Aristotle was 17, his father sent him to be educated at Plato’s Academy. Aristotle remained there for twenty years. After Plato’s death Aristotle founded his own school for studying Philosophy – which he called the Lyceum. The fact that Aristotle continued to be a philosopher shows how great an influence Plato had on him. The fact that he started a new, different school of philosophy shows that Aristotle disagreed with many of Plato’s beliefs. So, although he remained a philosopher all his life, Aristotle had a very different approach to philosophy from Plato. He said, ‘Plato is dear to me, but dearer to me is the truth.’ ARISTOTLE AND PLATO: BOTH PHILOSOPHERS Philosophy literally means love of wisdom. Both Plato and Aristotle look for a full explanation of reality Both believe that to understand reality you must understand yourself ‘Know yourself.’ (Plato) ‘All people by their nature desire knowledge.’ (Aristotle) PLATO’S APPROACH ARISTOTLE’S APPROACH TO PHILOSOPHY TO PHILOSOPHY Rational – using reason to understand abstract empirical – using research to understand ideas particular objects dual – reality has two levels: physical world and single – there is only one real world: what we abstract ideas experience logic – philosophy is the progression of ideas research – philosophy must study the world in a through careful steps towards final truth structured way towards general understanding Questions What do you think a philosopher would be like? What are the strengths and weaknesses of Plato’s approach to being a philosopher? What are the strengths and weaknesses of Aristotle’s approach to being a philosopher? Which do you think is better – and why? PLUS: Look at the famous painting of Plato and Aristotle by Raphael – reproduced on p. 33 of Bryan Magee, Story of Philosophy and at http://www.unesco.org/phiweb/uk/raphael/fresque/f2.html – how does the painting represent differences between Plato and Aristotle? 2 PLATO’S ANALOGY OF THE CAVE Plato’s analogy of the cave is the most famous aspect of his philosophy. Read: 1. The summary of the Analogy of the Cave in pages 10-11 of Roy Jackson, ‘Plato’s Analogy of the Cave’, Dialogue Magazine 17, Nov. 2001. 2. The summary of the Analogy of the Cave on page 31 of Bryan Magee, The Story of Philosophy. You could also read Plato’s original analogy, reproduced on pages 7-9 of Libby Ahluwalia, Foundation for the Study of Religion or at this link - http://plato.evansville.edu/texts/jowett/republic29.htm Use the information in these resources to annotate each stage of the cartoon above with a. what is happening in the story of the cave? b. what does it represent in Plato’s philosophy? 3 The Objects and the Shadows One of the most important aspects of Plato’s analogy of the cave is the difference between the shadows and the objects. The differences are summarised in the grid below. The shadows represent particular things in the world, and the objects represent their Forms. You will learn more about the Forms in the next section of this pack. SHADOWS representing PARTICULAR THINGS IN THE WORLD changing unreal projections image Uncertain OBJECTS representing THEIR FORMS clear real source truth certain The Form of the Good, as it is represented in the analogy of the Cave. At the end of the analogy of the cave, Plato says that the philosopher – once he has seen the Sun, the Form of the Good – will return into the cave out of a sense of duty to help those people who are ignorant within the cave. He will rule in the state in order to enable an ignorant society to be as close to the Good as possible – more on this in the next section. He will also teach an elite, who will become philosophers, to know the Form of the Good. The sun represents the Form of the Good. Impersonal power – ‘sustains everything else’ Source of reality – ‘responsible for everything that is right and fine’ Goal in reality – ‘greatest of all that is known, because it is the giver of knowledge’ (The Analogy of the Cave) How can someone learn about the Form of the Good? – the process of leaving the cave to become a philosopher He cannot be told the Form of the Good, because it is ultimate. He cannot find the Form of the Good with his senses, because it is an abstract idea. He cannot invent the Form of the Good, because it is eternal and changeless. BUT: he is capable of knowing the Form of the Good, if he uses his reason. SO: The person can learn about the Form of the Good by being questioned by a philosopher. The philosopher asks the person ‘what is Good?’, and the person gives an opinion about an example. Then the philosopher asks more questions to show the person why their opinion is not fully accurate. This will make the person turn away from that opinion and choose another opinion. So the philosopher will keep questioning them, getting them to turn away from their new opinion. The philosopher only ever asks questions. How can…? Don’t you think that…? What about…? Eventually the person will realise that there is no point using opinions to try to know the Good. Then they will turn away from opinion altogether, and start to use reason. Then they will know abstract, eternal, ultimate Good – even though they have never been told it. Summarising this process, Plato described the Form of the Good as the ‘goal at the end of questioning.’ A. B. How is this process represented in the analogy of the cave? What can the philosopher do to aid this process in others? What can’t he do? Answer the questions above. (The next section gives you much more information on the Forms, so don’t worry if this last section seems tricky at this stage.) 4 THE CONCEPT OF THE FORMS 1. 2. 3. Read Roy Jackson, Plato: a beginners guide, chapter three Read the text above and answer the question. Make a list of what you think are strengths and weaknesses of Plato’s theory of the Forms and compare it with the grid on the next page. 5 6 KEY FEATURES OF THE FORMS The text below, from Stephen Law’s The Philosophy Files, gives four points to answer the question, ‘what are Plato’s Forms like?’ Annotate the cartoons to show what beliefs of Plato’s they represent. 7 8 REASON AND KNOWLEDGE OF THE FORMS: Plato believed that there are two different levels of awareness, reason (rational awareness) and sense experience (empirical awareness). These levels of awareness fit with the two different levels of reality, the Forms and particular objects. Reason gives knowledge of the Forms, whereas sense experience gives only opinions about particular knowledge. Plato’s understanding of two levels of awareness is presented in the diagram below. PHILOSOPHER’S RATIONAL AWARENESS: THE TOP LEVEL UNCERTAIN OPINION cannot reveal cannot lead to ABSTRACT UNIVERSAL FORMS recognises judges is applied to SENSE EXPERIENCE cannot give CERTAIN KNOWLEDGE REASON CONCRETE PARTICULAR OBJECTS ORDINARY EMPIRICAL AWARENESS: THE BOTTOM LEVEL According to Plato, reason is accessible to all but only some – who become philosophers – choose to use it. Other people, ordinary people, choose to stay with empirical awareness and are only interested in sense experience. Note that Plato believed that knowledge of the Forms was certain because of what the Forms are. We usually consider certainty to be a psychological state, dependent on the outlook of the person who is perceiving something. But Plato thought that certainty depended on the object that is perceived. So the fact that the Forms are unchanging means that knowledge of the Forms is certain – the Forms cannot change, so once we know the Forms we must be right. Similarly the reason why sense experience is uncertain is that the objects of sense experience are changing – just because we know something about sense experience now, does not mean that we will always be right. If we think of certainty now as a purely psychological matter, it will be difficult to agree with Plato’s aiew. Note also that reason has complete priority over sense experience. If for example I have seen twenty beautiful things, or even twenty thousand beautiful things, I will never learn from them what beauty itself is. However, if I know beauty itself, I will always be able to tell whether or not any thing that I encounter is beautiful. The person who uses reason can always judge opinions. 9 THE FORM OF THE GOOD The Form of the Good and The Concept of the Forms The Forms are objective – meaning that they are actually real. They are not subjective – meaning that they are not just personal opinions. They exist in a Realm of the Forms, in a hierarchy. Plato keeps this hierarchy pretty unofficial, although some examples tell us a lot about how he viewed the world. The Form of Wisdom is higher than the Form of Courage – wisdom is intellectual, courage is to do with passion. The Form of the Bed is very low – it is only a physical thing. What Plato is definite about is that the Form of the Good is at the top of the hierarchy. Why is the Form of the Good at the top of the hierarchy? Whenever you know a Form, you know the perfectly good essence of the particular things. The Form of the Chair is the perfectly good essence of chairs Knowing the Form means that you recognise all the particular things Knowing the Form of the Chair means that you recognise all chairs The Form of the Good is the perfectly good essence of being good. So knowing the Form of the Good means that you can recognise all the Forms as perfectly good. So knowledge of the Form of the Good draws together knowledge of all other Forms. 10 The Form of the Good Read the three summaries of the Form of the Good. Make a list of key characteristics of the Form of the Good. 11 Why should one who knows the Form of the Good rule society? Plato believed that once someone knew the Form of the Good, they could function in society as a philosopher-ruler. This is what he meant by the process of returning to the cave after seeing the sun, in the Analogy of the Cave. ‘The sight of it [the Form of the Good] is necessary for proper conduct, either of your own private affairs or of public matters’ (The Analogy of the Cave) Knowledge of the Form of the Good enables the philosopher to judge opinions about goodness. This assumes, as Plato always did, that knowledge of ideas is greater than experience of events. It is not the person who has seen lots of transport systems who is best placed to judge a good transport system; they will be distracted by all the alternatives. The philosopher, who knows Good, will be able to see straight into the heart of the matter and know which system is closest to the Good. The philosopher will wish that he could stay in the higher world of just contemplating the Form of the Good – so he will not want to rule out of ambition or desire for power. He will only rule out of a sense of duty. And according to Plato ‘the less keen the rulers are to rule, the better the administration of the city will be.’ The people who ‘shadow-box with opinions’ always want to do things their way, whether it is the best way or not. The Form of the Good is impersonal – therefore the philosopher will not be swayed by personal opinions in ruling the city. He will be able to apply a fair, unbiased standard and make any action the best it can be – the closest it can be to sharing in the Form of the Good. A. What would be the problems in a society ruled by philosophers? B. Given all the problems, what value could there be in Plato’s idea of a philosopher-ruler? 12 13 THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN THE SOUL AND THE BODY Read: 1. Libby Ahluwalia, Foundation for the Study of Religion, pages 14-15 2. Jordan, Lockyer and Tate, Philosophy of Religion for A Level, page 3. The Text Above: from Stephen Law, The Philosophy Files Using the information from your reading: annotate the cartoons to show what beliefs of Plato’s they represent. Using the information from your reading: Make a grid of key terms that describe Plato’s understanding of the soul and key terms that describe Plato’s understanding of the body – try to put related terms together in the grid. You should often get opposites, as in the example below. BODY SOUL mortal immortal Plato understood immortality to mean existing forever, both in the past and in the future. Plato presented a deductive argument for the immortality of the soul. A deductive argument is a logical argument in which if the two reasons are true, the conclusion must be accepted. Plato argued: First Reason: A thing can be destroyed only by separation of its parts Second Reason: The soul (the essence of the person) has no parts Conclusion: The soul cannot be destroyed – it is immortal If the two reasons are true then the conclusion must be true. So the only way to attack this argument is to dispute the reasons. The first reason could be disputed by arguing that an object with no parts could be destroyed, for example by erosion. It could also be argued that a person is essentially a changing process, which would dispute the second reason. Plato believed that philosophy was a preparation for death. By focusing on abstract, eternal ideas the philosopher could become disinterested in the body. Then his soul would leave the body behind at death and return to the realm of the Forms. Plato presents his hero and mentor Socrates as the philosopher completely prepared for death. Socrates is asked by his companion Crito: ‘How shall we bury you?’ And Socrates answers: ‘Any way you like. Do you think you can catch me and I won’t slip between your fingers?’ 14 ESSAYS Titles AO1 – select and demonstrate knowledge and understanding EITHER: Explain the meaning of Plato’s analogy of the cave. [33 marks] Work through Plato’s analogy of the cave in detail stage by stage At each stage explain what it means eg. describe the situation of the prisoners in the cave – and explain what it means then describe....... – and explain what it means and so on. OR: Explain Plato’s theory of the Forms. [33 marks] Explain what the Forms are, how they are known, why they are known, and how the Form of the Good is the highest Form. and AO2 – sustain a critical line of argument and justify a point of view Is Plato’s Form of the Good a useful concept? [17 marks] Answer in two paragraphs – 1. it is useful in one way; BUT 2 it is not useful in another way (Notice that whichever AO1 essay you do it is likely to end with an explanation of the Form of the Good, so that you are ready to go straight into the AO2 with a point of view) Resources There are three very useful resources in the library Roy Jackson, ‘Plato’s Analogy of the Cave’ in current Dialogue Magazine (Nov 01). Despite the title, there’s a bit about the Forms as well. Dialogue is kept in the magazine section of the library There’s more detail in Roy Jackson, Plato: A Beginner’s Guide (especially chapters 3-5) and in Libby Ahluwalia, Foundation for the Study of Religion (pages 4-19). Both in the usual Philosophy of Religion section (210) Lengths The AO1 essay will be about two sides and the AO2 essay will be about one side 15