Europe : Vanishing Mediator

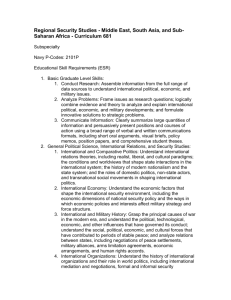

advertisement