Are Multiples Growth Restricted

C620R9011 1

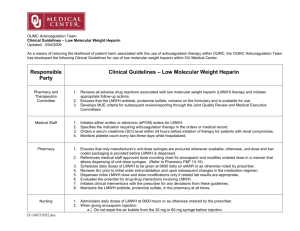

Is There Room for LMWH Treatment in Obstetrics &

Gynecology?

D. Blickstein

Institute of Hematology, Rabin Medical Center, Beilinson Campus, Petach Tikva, and the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Summary

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) are substituting unfractionated heparins for various indications for anticoagulant therapy in perinatal medicine. Compared with unfractionated heparin, LMWHs have longer bioavailability and lower frequency of serious side effects, and have a more predictable dose-response without laboratory monitoring. LMWHs are more convenient to the patients and safe for the fetus. In addition to the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolic (VTE) events throughout gestation and puerperium, LMWHs are currently prescribed for the prevention of recurrent pregnancy complications. Planned induction of labor or elective abdominal birth is desirable in order to decrease bleeding and regional analgesia-related complications.

Introduction

Anticoagulation is primarily indicated for treating deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), or for thromboprophylaxis. The latter is used in either patients at constant risk or in those who are at increased risk of thrombosis for a limited duration.

At present, some inherited and acquired conditions, termed thrombophilia, are recognized as increasing the thromboembolic risk during pregnancy and puerperium. [1] In addition to DVT and PE, thrombophilia was also associated with vascular pathologies in the uteroplacental unit leading to adverse pregnancy outcome [1-3] and to a wide range of indications for anticoagulation during pregnancy and puerperium.

Following the seminal study of Hall et al [4] who pointed to the adverse fetal and neonatal outcome related to warfarin anticoagulation, it is currently restricted to specific indications when other anticoagulants are judged to less adequate.[5] Treatment with heparin, although safe for the fetus, may cause maternal side effects and needs close monitoring. During the last two decade a third preparation – low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) – has been introduced. This paper examines the use of LMWH in perinatal medicine.

What Is LMWH ?

Heparin binds to antithrombin III (ATIII), to convert antithrombin from a slow progressive thrombin inhibitor to a very rapid inhibitor of thrombin and factor Xa.

LMWH are fragments of approximately one third the size of heparin, produced by chemical or enzymatic depolymerization. These fragments bind to ATIII, inactivate mainly factor Xa, and are less likely to inactivate thrombin because the small fragments cannot bind simultaneously to both thrombin and ATIII.[6] Many forms of LMWH are available. A short list of the various LMWH preparations approved for use in the USA,

Canada, and Europe, is shown in Table 1. The preparations may not be clinically interchangeable because they have different pharmacokinetic and anticoagulant characteristics. Activity of LMWHs is measured by the t

½

anti-Xa (hrs) and this value indirectly effects dosing. A higher anti-Xa to anti-IIa ratio representing the better affinity of the product to inactivate factor Xa.

C620R9011 2

Table 2 shows the advantages and disadvantages of LMWH compared to unfractionated heparin. Heparin has a lower bioavailability and shorter half-life and checking the partial thromboplastin time (PTT) is obligatory during treatment. By contrast, levels of anti-Xa during treatment with LMWHs are rarely monitored and there is a predictable doseresponse relationship, which translates to weight-adjusted dosing without laboratory monitoring. Thus, despite the fact that LMWHs are more costly than unfractionated heparin, saving hospital costs and monitoring counterbalance this expense. Altogether,

LMWHs are as effective and safe as unfractionated heparins, and are more convenient for the patient. It should be stressed that LMWHs are by all means heparins with potential heparin-related side effects (such as hemorrhagic events, osteoporosis, and heparininduced thrombocytopenia) and cross-sensitivity. Both heparin and LMWHs do not cross the placental barrier.[8] One should consult with the local health authority concerning the available LMWH that are approved for use during pregnancy and puerperium.

The various regimens of unfractionated heparin and LMWH are summarized in Table 3.

LMWH in the Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnancy occurs approximately 6 times more than in the non-pregnant state. [9] PE occurs in about one sixth of the patients with untreated

DVT and is the most common cause of maternal mortality. [9]

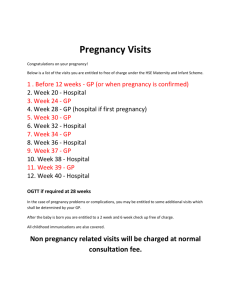

Guidelines regarding the management of VTE during pregnancy are regularly updated.

Recently, the 6 th

American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy (2001) suggested that LMWHs are as effective and safe as unfractionated heparin for the treatment of acute DVT. The current recommendations for the treatment of VTE during pregnancy are either (a) weight-adjusted dose LMWH throughout pregnancy, or (b) intravenous heparin for at least 5 days followed by PTTadjusted dose of heparin for the remaining pregnancy. Postpartum anticoagulation therapy should be administered for at least 6 weeks.

Thromboprophylaxis with LMWH

The overall risk of DVT during pregnancy (0.05-1.8%) is higher in women with a previous event of DVT, with a recurrence rate of 1:71 cases. [9] Currently, five groups of pregnant patients at increased risk of VTE have been identified.

1.

VTE associated with a transient risk factor (i.e., with bed-rest, oral contraception, etc.). Management includes close observation during pregnancy and postpartum anticoagulants.

2.

Single episode of idiopathic VTE.

Management includes one of the options:

(a) close observation, (b) mini- to moderate dose unfractionated heparin, or (c) prophylactic LMWH. All patients should receive postpartum anticoagulants.

3.

Single episode of idiopathic VTE and thrombophilia. The same recommendations as in group 2, however, because of the higher risk for VTE, thromboprophylaxis in patients with ATIII deficiency is suggested.

4.

No prior VTE and thrombophilia.

These patients can be offered one of the options: (a) close observation, (b) minidose unfractionated heparin, or

(c) prophylactic LMWH. All patients should receive postpartum

C620R9011 3 anticoagulants. Thromboprophylaxis is strongly encouraged in patients with ATIII deficiency.

5.

Multiple episodes of VTE and/or long term anticoagulation .

Management includes one of the options: (a) PTT-adjusted dose of unfractionated heparin, (b) prophylactic LMWH, or (c) weight-adjusted

LMWH. These patients should receive long-term anticoagulation postpartum.

To recap, prophylactic treatment should be tailored according to the risk group. Both heparin and LMWH are options, but it appears that LMWH will largely replace unfractionated heparins. [10]

LMWH and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome

Recent studies suggested that inherited thrombophilias are not only associated with increased risk of VTE during pregnancy and puerperium, but also with an increased risk of vascular pathologies in the uteroplacental unit leading to adverse pregnancy outcome, such as first and second trimester miscarriages, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), intrauterine fetal death, placental abruption, and preeclampsia. [1, 11]

Critical reading of the literature reveals two nuances on these aspects. The data of the

European Prospective Cohort On Thrombophilia (EPCOT) study show a certain contribution of thrombophilia to adverse perinatal outcome [12] whereas numerous series show a definitive role of thrombophilia in the pathogenesis of several adverse pregnancy outcomes. [13] There are at present two main controversies related to the validity of evidence associating thrombophilia and gestational thromboembolic phenomena and to the appropriate selection of patients and the timing of prophylactic anti-thrombotic therapy to prevent pregnancy loss and associated pregnancy complications. [14] These conflicting views may be clarified by several ongoing multi-center prospective studies.

Data on treatment for women with inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy loss is mostly uncontrolled and based on small series. The optimal dosage of LMWH to prevent thrombophilia-associated adverse pregnancy outcome is also unknown. [15]

The 2001 ACCP Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy recommends evaluation for inherited thrombophilia as well as for the acquired antiphospholipid antibody (APLA) syndrome in women with recurrent pregnancy loss, prior severe preeclampsia, IUGR, placental abruption, or otherwise unexplained fetal demise.

Management of pregnant patients is then subgrouped into five categories.[10]

1.

Pregnant patients with APLA and previous pregnancy complications . Treatment should consist of low dose aspirin plus either of the following options: (a) mini- to moderate dose unfractionated heparin, or (b) prophylactic LMWH.

2.

Homozygous women for MTHFR . These should be treated with folic acid before pregnancy or as soon as pregnancy is confirmed.

3.

Women with thrombophilia and previous adverse pregnancy outcome . One should consider low dose aspirin plus either (a) minidose heparin, or (b) prophylactic LMWH. These patients should receive postpartum anticoagulants.

4.

Women with APLA syndrome and history of VTE . Long-term anticoagulation (warfarin) should be switched to either adjusted-dose

C620R9011 4 unfractionated or LMW heparins throughout pregnancy and resumption of the long-term anticoagulant postpartum.

5.

Women with APLA syndrome but without history of VTE or pregnancy loss . Four approaches have been suggested: (a) surveillance only, (b) mindose heparin,(c) prophylactic LMWH, or (d) low dose aspirin.

Peripartum LMWH

Persistent peripartum anticoagulation may complicate delivery. No significant difference in hemorrhagic complications was observed between LMWHs, mainly enoxaparin and dalteparin, and unfractionated heparins. Although bleeding complications appear to be very uncommon with LMWH, it was suggested to discontinue therapy 24 hours prior to invasive procedures or before induction of labor. [16]

The incidence of neurological complications from hemorrhage is estimated to be less than

1:150,000 epidurals and less than 1:220,000 spinal blocks, and obviously, traumatic needle or catheter placement may increase the risk of a spinal hematoma. Because the anti-Xa level does not predict the risk of bleeding, the concern about regional anesthesia explains why labor induction or cesarean birth should be a planned elective procedure in women receiving LMWHs. To reduce the risk of anesthesia-related hematoma, regional blockade should start at least 12 hours after the last prophylactic LMWH dose and longer

(24 hours) if the patient receives weight-adjusted dose of LMWH. When continuous epidural analgesia is performed, LMWH can be restarted 2 hours after catheter removal.

Dealing with Complications

Bleeding is a rare complication in patients receiving LMWH, and should be even rarer when a planned peripartum management is carried out. However, when bleeding occurs, the antidote is protamine sulfate. One should remember that protamine sulfate incompletely neutralizes the anti-Xa activity of LMWH, probably because it does not bind to very low molecular weight components. [17]

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a rare complication of LMWHs.

Nonetheless, a platelet count should be done every four days during the first month, and monthly thereafter. Patients with the APLA syndrome are more prone to develop HIT.

When continued anticoagulation is required, one should switch to the heparinoid danaparoid sodium (Orgaran). [16] This effective agent, with an anti-Xa to anti-IIa ratio of 20, has limited cross-reactivity with LMWH and was safely used during pregnancy.

Data on heparin-induced osteoporosis are of limited application to the pregnant state. [18]

It is nonetheless advisable to prescribe supplemental calcium for malnourished patients or when weight-adjusted LMWH is administered throughout pregnancy.

Owing to the cross-sensitivity of the LMWHs, heparin-induced skin reaction should be treated by changing to the heparinoid danaparoid sodium.

References

1.

BLICKSTEIN D , BLICKSTEIN I. Fetal consequences of maternal inherited hypercoagulable states (thrombophilia). In: Fetal medicine: The clinical care of the fetus as a patient. Chervenak FA, Kurjak A, (eds), Parthenon Publishing,

Lancs, 1999; pp. 288-93.

2.

MOUSA HA, ALFIREVIC Z. Thrombophilia and adverse pregnancy outcome. Croat Med J 42:135-145, 2001.

C620R9011 5

3.

BRENNER B. Inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy loss. Thromb

Haemost 82:634-640, 1999.

4.

HALL JG, PAULI RM, WILSON KM. Maternal and fetal sequelae of anticoagulation during pregnancy. Am J Med 68:122-40, 1980.

5.

CHAN WS, ANAND SS, GINSBERG JS. Anticogulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. Arch Intern Med 160:191-6, 2000.

6.

HIRSH J, WARKENTIN TE, SHAUGHNESSY SG, ANAND SS,

HALPERIN JL, RASCHKE R, GRANGER C, OHMAN EM, DALEN JE.

Heparin and low molecular weight heparin. Chest 119:64S-94S, 2001.

7.

SAMAMA MM, GEROTZIAFAS GT. Comparative pharmacokinetics of

LMWHs. Semin Thromb Hemost 26:31-38, 2000.

8.

FEJGIN MD, LOURWOOD DL. Low molecular weight heparins and their use in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv 49:424-31, 1994.

9.

ELDOR A. Thrombophilia, thrombosis and pregnancy. Thromb Haemost

86:104-111, 2001.

10.

GINSBERG JS, GREER I, HIRSH J. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy. Chest 119:122S-131S, 2001.

11.

BRENNER B. Inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy loss. Thromb

Haemost 82:634-640, 1999.

12.

PRESTONEON FE, ROSENDAAL FR, WALKER ID, BRIET E,

BERNTORP E, CONARD J, ET AL. Increased fetal loss in women with heritable thrombophilia. Lancet 348:913-16, 1996.

13.

KUPFERMINC MJ, ELDOR A, STEINMAN N, MANY A, BAR-AM A,

JAFFA A, FAIT G, LESSING JB. Increased frequency of genetic thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. N Eng J Med 340: 9-13, 1999.

14.

BLICKSTEIN D. Thrombophilia in Obstetrics and Gynecology:

Introduction. In Ben- Refael Z, Shoham Z. (eds.) The Second World Congress on Controversies in Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. Monduzzi Editore,

Bologna, Italy, 2001; pp. 105-109.

15.

BRENNER B. Pregnancy and thrombophilia: Aare they related ? Can the complications be prevented ? In Ben- Refael Z, Shoham Z. (eds.) The Second

World Congress on Controversies in Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility.

Monduzzi Editore, Bologna, Italy, 2001; pp. 119-124.

16.

GRIS JC. Risks and benefits of low molecular weight heparins in obstetrics and gynecology. In Ben- Refael Z, Shoham Z. (eds.) The Second World

Congress on Controversies in Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. Monduzzi

Editore, Bologna, Italy, 2001; pp. 125-128.

17.

HIRSH J, LEVINE MN. Low molecular weight heparin. Blood 79:1-17,

1992.

18.

CASELE HL. Prospective evaluation of bone density in pregnant women receiving the low molecular weight heparin enoxaparin sodium. J Matern Fetal

Med 9: 122-125, 2000.

C620R9011 6

Table 1. Characteristics of some common LMWH preparations. Adapted from [7]

Table 2. Comparison between heparin and LMWH

Table 3. Regimens of unfractionated heparin and LMWH.