assessment-task-3-ancient-history-research-essay

advertisement

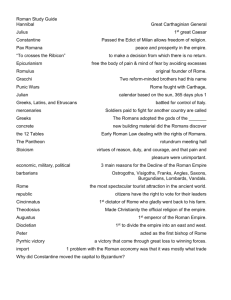

Assessment Task #3: Year 11 Ancient HistoryHistorical Investigation Teacher: Mr Hendry Class: Year 11 Ancient History By Benjamin French Essay Question: “Outline the perceived issues facing the Roman Empire during the Crisis of the Third Century and assess the effectiveness of Diocletian’s response.” The Crisis of the Third century, also known as the “Military Anarchy” or the “Imperial Crisis” refers to the stagnation, decline, and near collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 285 AD. Primarily caused by three contemporary crises, internal civil war, external invasion, and economic turmoil, there were abrupt changes brought about as a direct result of the disorder, greatly affecting a number of the Roman world’s core institutions, including society, economic life, religion and ultimately lifestyle foundations. In this short period of time, relative to the length to which they had survived almost unrivalled beforehand, the transformations were so significant that it is widely accepted in historical periodization that the crisis is a fundamental marking point in identifying the progression from classical to late antiquity, and essentially the conclusion of the Crisis with the accession of Diocletian is seen as the division between these two epochs in ancient history. Although Aurelian had been succesful in restoring the empire’s borders and resisting foreign threats, problems that rested at the heart of Roman civilization continued to surface. In particular, the right of succession had never been clearly articulated, resulting in incessant civil unrest regarding incoming and outgoing Emperors, and being responsible for much of the underlying instability which had plagued the empire for centuries. Also, the sheer size of the Roman Empire, which spanned an immense portion of settled land, made it considerably difficult for a sole autocratic leader to administer threats emanating from multiple cities and provinces at one given time. These concerns, among several others, would be drastically addressed by Diocletian, allowing the Empire to survive in the West for another century, and in the East for another 1000 years1. The situation faced by Rome became ominous when, in 235, Emperor Alexander Severus, the last Roman Emperor of the Severan dynasty and who had ruled for over a decade, was assassinated by his own legions following a failed campaign against Germanic peoples2. Recognized as almost the last straw in the long-running principate system initiated by Augustus3, the assassination of Severus ignited the chaotic beginnings of the Crisis, with the direct aftermath seeing Roman army generals fighting each other for control of the empire, thus neglecting their military duties in preventing foreign invaders, which had long been a defining strength of Roman defence. Eventually, the ruling of the empire became calamitous, with imperial power being held by roughly 20 to 25 individuals comprised mainly of high ranking generals, who were only to lose it a few years later as a result of, primarily, defeat in battle and murder. Provinces soon became victims of repeated raids by foreign tribes, who quickly took their opportunity to take up Roman territory, such as the Carpians, Goths, and Vandals along the Rhine and Danube River in the western part of the empire, in addition to the attacks from the Sassanids in the eastern sects. With external borders on a constant threat, by 258 internal division set in, with the empire 1 His reforms completely saved the East, and gave the West another good 100 years. (Diocletian and the Roman Recovery, by Stephen Williams) 2 He therefore hoped that the threat of war alone might be enough to bring the Germans to accept peace. It worked indeed and the Germans agreed to sue for peace, given that they would be paid subsidies. However, for the Roman army this was the final straw. They felt humiliated at the idea of buying the barbarians off. Alexander and Julia Mamaea were both murdered by their own troops (March AD 235). http://www.roman-empire.net/decline/alex-severus.html 3 Early phase of Imperial Roman government http://www.unrv.com/early-empire/principate.php seperating into three competing states in order to survive; Gaul, Britain and Hispania broke off to form the Gallic Empire4, and two years later in 260, the eastern provinces of Syria, Palestine and Aegyptus turned independent in the form of the Palmyrene Empire (with Sassanid patronage), leaving the remaining Italian-centered Roman empire stranded without support in the middle. Naturally, this disorder on both frontiers paved the way for regional rebellions, frequent usurpations of power5 and, consequently, profound economic hysteria and collapse. The empire was already at risk of astronomical hyperinflation due to generations of coin devaluation, which had started during the earlier part of the Severan dynasty – as each of the short-lived members took reign, they saw the need to raise funds quickly to account for the military’s “accession bonus” and the simplest path to take was to reduce the amount of silver in coins and compensate with far cheaper metals6. As a result, inflation soared and the currency was rendered almost incapable of sustaining value and trade was by barter, not money7; through this, every aspect of Roman lifestyle had been severely impacted upon. Perhaps the most destabilizing effect of the Crisis from an economical viewpoint was the disconnection of Rome’s extensive internal trade network. Ever since Roman peace8, Imperial Rome’s economy relied heavily on trade between the Mediterranean ports and across Rome’s vast road system. Merchants were able to safely travel from either end of the Empire within a few weeks, transporting agricultural goods produced in the provinces, and manufactured goods generated by the larger cities of the East 9. 4 At around the same time, the western provinces of Gaul (modern France) and Germany set up their own Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum) under their chosen emperor, Postumus. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/thirdcenturycrisis_article_04.shtml 5 After the assassination of Severus Alexander in 235 AD, the soldiers in various parts of the empire proclaimed fifty emperors in about the same number of years. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/thirdcenturycrisis_article_04.shtml No emperor could be secure on the throne, and during the 50-year period from A.D. 235 to 284 there were approximately 35 emperors, of whom only one died a natural death. Emperors had to spend most of their time fighting would-be usurpers. http://isthmia.osu.edu/teg/50501/4.htm 6 Predictably, this caused rising inflation and by the time the Crisis cooled, the old coinage infrastructure had nearly disintegrated. Certain taxes were paid in kind and values were often estimated in bronze or bullion coinage. Meanwhile, true values continued to be represented by gold coinage, but the almost purely solid silver coin, the denarius, which had been used for 300 years had disappeared and been replaced by the antoninianus, a double denarius that rapidly became debased to bronze and reduced in size. http://www.romanorum.com.au/Info/Articles/Tables.htm 7 The third century witnessed a tremendous inflation and the currency collapsed; the empire nearly reverted to a "natural economy" (based on barter, with no coinage used). http://isthmia.osu.edu/teg/50501/4.htm 8 Pax Romana http://www.unrv.com/early-empire/pax-romana.php 9 The historian Henry Moss describes the situation as it stood before the Crisis: Along these roads passed an ever-increasing traffic, not only of troops and officials, but of traders, merchandize and even tourists. An interchange of goods between the various provinces rapidly developed, which soon reached a scale unprecedented in previous history and not repeated until a few centuries ago. Metals mined in the uplands of Western Europe, hides, fleeces, and livestock from the pastoral districts of Britain, Spain, and the shores of the Black Sea, wine and oil from Provence and Aquitaine, timber, pitch and wax from South Russia and northern Anatolia, dried fruits from Syria, marble from the Aegean coasts, and – most important of all – grain from the wheat-growing districts of North Africa, Egypt, and the Danube valley for the needs of the great cities; all these commodities, under the influence of a highly organized system of transport and marketing, moved freely from one corner of the Empire to the other. H. St. L. B. Moss, The Birth of the Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1935, reprint Oxford University Press, January, 2000) With the Crisis, however, this systematic trade structure soon crumbled, as civil unrest rendered it no longer a safe and viable means for merchants to travel as they once had, not to mention the financial turmoil at the centre of the conflict. These complications, in many ways, saw major changes in lifestyle that foreshadowed the coming of the Middle-Ages with regards to the self-sufficient house economy and the prototype for serfdom which took on a central role in the feudal class system. Despite numerous attempts to salvage it, the Roman economy never adequately recovered, with the ongoing political and military crisis compunding the problems, as the state often did not have the finances to cover expenses. 10 Nonetheless, the reign of Aurelian (270-275) unified the empire in its entirety, following decades of widespread internal revolt, the loss of two-thirds of its territory to break-away empires and large scale barbarian invasion. He turned his attention to these immediate problems faced by the empire after securing his power base and the support of the people, and his achievements signaled the beginning of the end for the Crisis. In a sense, his reformatory mindset, inspired by the efforts of Gallienus11 (253-68), lay the perfect foundation for Diocletian, one of the greatest of Rome’s later emperors (reign from 284-305), additionally settling many important inner workings of the imperial landscape, such as the economy, religious allegiances, administration of food reserves and directing punishment for the transgression of many public officers and high ranking generals. From this, Diocletian set about his own work. Hailed emperor on 20 November, 284 AD, he realized the empire’s crucial weaknesses in the indecisive manner by which the armies made and deposed emperors, and its need to establish concrete principles regarding succession12. Although Rome had long been a formidable presence throughout Europe and around the Mediterranean, with revolutionary military, economic and social structures, it had suffered considerably on an internal level as a result of the autocratic nature of ruling and succession, resulting in numerous assassination plots and civil unrest. Moreover, its vastness of territory had led to complications with previous emperors who ruled the entire empire from one central point; so, too the surprise of most at the time13, Diocletian addressed this by appointing his fellow soldier, Maximian, as Caesar14, thus dividing the empire so that Diocletian could give his full and urgent attention to the issues on the Danubian borders and have someone he could trust to oversee government. Following several years of hard, energetic and successful campaigning as a shared unit, in 293 Diocletian adopted Galerius as his eastern Caesar15, while Maximam did the same with Constantius I in the west, thus establishing an innovative quadruple administration (in which a Caesar was to overtake his Augustus16 in the 10 The political and military crisis heightened the economic problem; and the economic problem contributed to the political and military difficulties since the state frequently did not have the money to cover expenses. http://isthmia.osu.edu/teg/50501/4.htm 11 Although his reign saw chunks of the empire break away, Gallienus is now seen to have laid the reforms for its subsequent recovery (Nigel Rodgers, The Rise and Fall of Rome, pg 72, Lorenz Books, Anness Publishing Ltd 2004) 12 Nigel Rodgers, The Rise and Fall of Rome, pg 73, Lorenz Books, Anness Publishing Ltd 2004 Then, much to everyone's surprise, Diocletian, in November AD 285 appointed his own comrade Maximian as Caesar and granted him control over the western provinces. http://www.roman-empire.net/decline/diocletian.html 14 Was eventually promoted to the rank of Augustus because of his achievements, although Diocletian remained senior ruler, holding a veto over any edicts made by Maximan (Ibid) 15 Junior emperor/heir (Ibid) 16 A Caesar was to succeed his Augustus in this Tetrarchy [The Rise and Fall of Rome (Op. Cit)] 13 event of their death/retirement) which become known as the Tetrarchy. It was a sysematic division, with each tetrarch holding their respective capital cities in a territory under their control- Triar and Milan in the west, Thessalonica and Nicomedi (north Turkey) in the east.The theory was that by shaping a system by which heirs to the throne were appointed by merit, they could gain invaluable experience as Caesars long before they assumed the vacant position of Augustus17. Importantly, in order to sustain unity, the tetrarchy did not “split” the empire into separate parts as such, but was just ruled by four men to increase the effectiveness of authority to both remote and central areas. Rather than having military commanders, there were expert jurists and adminstrators in charge of imperial affairs, leading to a far more efficient infrastructure18 and in doing so he reduced the power of the senate19. To address the problem of revolt and assassination, Diocletian elaborated the imperial court greatly and initiated a semi-divine style pattern of worship for emperors; with palaces, basilicas, monuments and rituals such as kneeling before the emperor and kissing the robe20 Another major reform which came about through Diocletian was the adoption of a two-tier administrative system; he doubled the amount of provinces (which were overseen by twelve dioceses21), thus making them significantly smaller and reducing their power to rebel, as well as expanded and re-arranged the army, firstly by reintroducing conscription for Roman citizens and then creating a fixed set of frontier troops and Palatini22directly at the disposal of the emperor. This proved beneficial, contributing to victory over the Persians and extension of the frontier further into the east by 297 AD- furthermore, Britian had been re-instated to the empire by Constantius during this time. However, with the major reforms in military and government- and indeed, official attempts to control and stabilise all aspects of life-, there came an enormous financial burden. Being unable to rekindle the old system by re-issuing defunct coinage, and knowing of the strain that the tax rises were having on the general population, his government administered a detailed taxation system which allowed for regional variations of harvests and trade. This was almost a class-based implement- areas with greater wealth and fertile soil were taxed harder than the poorer communities, thereby making it more equitable23. With this, however, he was unable to check inflation, and his attempt to curtail this, the Edict of Maximum Prices in 301 AD, tried to fix prices and wages, but only managed to negate his earlier regional variations policy and, 17 if it worked like this in a cyclical motion then it was hoped that, in time, the problem of succession would soon be resolved by the best possible man for the job being in power at all times. 18 The administration of government was largely left in the hands of the prefects. They were no longer really military commanders, but far more they were expert jurists and administrators overseeing imperial administration. http://www.roman-empire.net/decline/diocletian.html 19 Diocletian also expanded the policy of third-century emperors of restricting the entry of senators into high-ranking governmental posts, especially military ones. http://www.roman-emperors.org/dioclet.htm 20 All this was no doubt introduced to yet further increase the authority of the imperial office. Under Diocletian the emperor became a god-like creature, detached from worldly affairs of the lesser people around him. (Ibid) 21 Sources conflict over whether there was 12 or 13 dioceses 22 Mobile forces [The Rise and Fall of Rome (Op. Cit)] 23 Fairer, more proportioned system additionally, take away goods from the markets24, keeping workers to their jobs like serfs25. Moreover, Diocletian’s religious policy was unsucccesful. Seeing the need to bolster Roman traditions and return it to worship of the old deities with the ultimate goal of using it as a unification medium,26 in 298 AD he set about persecuting Christians27, who he regarded as blasphemers and followers of foreign cults, and grew more ruthless in 303 AD, issuing an official edict that ordered the destruction of all chruches and scripture documents within the empire. He also punished all within Rome who refused to adhere to his revival of the Roman gods- even those within his own administration, dismissing them immediately if they disobeyed his will28. In his more Christianized east, several thousands were martyred from 303 AD to 311 AD, six years after he was no longer Emperor, and many more renounced their faith merely to stay alive. Towards the end of his two-decade long reign, Diocletian outlined a plan to ensure that Rome would survive sufficiently as a power after his time in charge. This involved the identification of key roles and occupations that would have to be performed, known as the “compulsory services”. 29 The need to instill these basic positions signified the utter turmoil in which Rome had been embroiled for much of the third century, and he made them of a hereditary nature, meaning people who grew up in a family of a particular occupation were bound to that role, and they became tired of the laws, suggesting that they were often ignored.30 On the first day of May, in 305 AD, tired by his long reign and recovering from a serious illness, Diocletian abdicated office31 , persuading a relucant Maximian to follow suit. He was also determined to see his plans for succession put into practice, and Constantius and Galerius became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were selected, Maximinus (305-313) in the east and Severus (305- 307) in the west. He retired to his palace in Dalmatia, returning only once to attempt to restore peace among his quarrelling successors, for the principles of the Tetrarchy were not working at all as intended- he died eight years later in his bed, by most accounts disappointed at the way his plans were unfolding. 24 A "Maximum Price Edict" issued in 301, intended to curb inflation, served only to make goods unprofitable to sell and drive them onto the black market Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina http://www.romanemperors.org/dioclet.htm 25 His notorious Edict of Maximum Prices in AD301, which fixed prices and wages, merely meant that goods disappeared from the markets, although workers were increasingly tied to their jobs like serfs. http://www.romanempire.net/decline/diocletian.html 26 But Diocletian, the great reformer of the empire, should also become known for a very harsh persecution of the Christians. Trying to strengthen Roman traditions, he much revived worship of the old Roman gods (Ibid) 27 Encouraged by the Caesar Galerius, Diocletian in 303 issued a series of four increasingly harsh decrees designed to compel Christians to take part in the imperial cult, the traditional means by which allegiance was pledged to the empire. This began the so-called "Great Persecution." Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina http://www.romanemperors.org/dioclet.htm 28 All soldiers and administrators were ordered to make sacrifices to the gods. Anyone who refused to do so, was immediately dismissed. (Ibid) 29 In order to assure the long-term survival of the empire, Diocletian identified certain occupations which he felt would have to be performed. These were known as the "compulsory services." They included such occupations as soldiers, bakers, members of town councils, and tenant farmers http://www.roman-emperors.org/dioclet.htm 30 The repetitious nature of these laws, however, suggests that they were not widely obeyed (Ibid) 31 The first emperor to voluntary resign from the post, which was an achievement in itself in not being either usurped or assassinated [The Rise and Fall of Rome (Op. Cit)] During the Crisis of the Third century (235-285), in which the Roman Empire was left in a state of intense chaos due to the onset of internal civil war, external invasion, and economic turmoil, there was significant change in all core institutions and facets of life- perhaps rapid and panic driven, but necessary change nonetheless for the empire was on the brink of collapse at every corner. Each Emperor was faced with the immense challenge of keeping such a vast community together as one whilst dealing with numerous imminent threats, with only some rising to the task. Gallienus (253-68) laid the foundations, upon which Aurelian (270-275) immediately built, and finally Diocletian began the long, tiresome process of reformation. His ideals were not always met with great support, and his initiatives did not always work out, but the sheer size of his campaign cannot be understated- a mere soldier he once was32, Diocletian kept an entire empire united through his inspired vision during the whole of his reign and went some way towards restoring it to normality. Perhaps Roman civilization had run the primary length of its course, and thus was not ready, or able, to bear the radical changes that he implemented across all boards, but still his efforts were revolutionary and underpinned the whole later empire, as it survived in the west for another century before it was separated, and in the east for another 100 years prior to the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks. The influence that Diocletian’s actual reforms as such had on these successes would have to be called into question, as his ideals did not pan out as he intended, and with each new emperor came a different vision. What cannot be denied, however, is the extent of his reforms and their immediate impact value, but the intense nature of the changes over such a short period of time proved to be unhealthy. His reforms in the areas of succession, tetrarchy and the military seemed to be working, but as soon as he retired office failed to come to fruition, with his other plans regarding religious unity, finance and occupation struggling to find their feet even during his reign. They were effective in a sense, but not quite close to the degree they were intended. This was through no fault of his own as Rome was already in a wider state of literal disrepair, and he had very little option as Emperor than to attempt these wholesale changes, much like other rulers have tried and failed throughout the world before and after his era. Thus the old adage remains universally true- history always repeats itself. By Benjamin French Diocletian was one of the greatest of Rome’s later emperors, recasting the empire in a bureaucratic, half-oriental mode…an achievement for a man who remained, beneath his imperial splendour, a simple Illyrian soldier. [The Rise and Fall of Rome (Op. Cit)] 32