wp_retention_synthesis

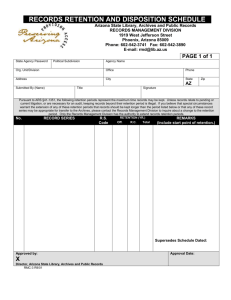

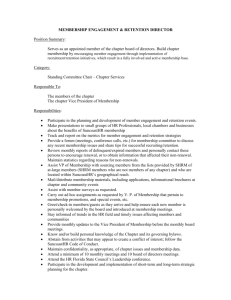

advertisement