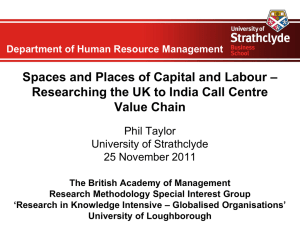

Union Formation in the Indian Call Centre/BPO Industry

advertisement