FOREIGN LANGUAGE IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL:

advertisement

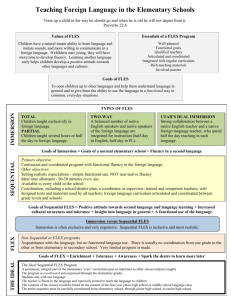

FOREIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BOARD RETREAT PACKET Page 1 of 14 Elementary School Foreign Language Programs SOURCE: http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-9212/programs.htm ERIC Digests A wide range of elementary school foreign language programs have been designed for the English-speaking child. These programs vary in intensity and outcome, depending on the goals and the availability of time and resources. Before starting a new language program, teachers and administrators should consider all possible program models and select the one that corresponds best to their goals and available resources. At one end of the spectrum are total immersion programs, where virtually all classroom instruction is in the foreign language. At the other end are foreign language experience (FLEX) programs, where classes may meet only once or twice a week and where the goal is not to develop language proficiency, but rather to introduce children to one or more foreign languages and cultures. Elementary school foreign language programs fall into the following broad categories: total immersion, partial immersion, content-based FLES (foreign language in the elementary school), regular (non content-based) FLES, and FLEX. WHAT IS REGULAR FLES? FLES programs were very popular in the 1960's and enjoyed much public and government support. During the 1970's, however, national priorities changed and support for FLES programs declined, causing many to be discontinued. The 1980's have seen the rebirth of FLES programs due, in part, to a renewed national emphasis on foreign language competency. The new FLES programs have learned from and improved upon the earlier ones. FLES programs now focus less on the teaching of grammar, and more on the development of listening and speaking skills and on cultural awareness. Grammar is not ignored, but is learned indirectly rather than through direct instruction. FLES programs follow the natural sequence of language learning: understanding > speaking > reading > writing. The primary stress is on understanding and speaking. Instructional techniques appropriate for young children have been developed; physical activity and concrete experiences play an important role. Visuals, manipulatives, and realia are a crucial part of the FLES classroom, and the typical lesson plan includes songs, rhymes, games, play-acting with puppets, and other physical activities that appeal to the younger child. FLES classes usually meet two to five times a week for 20 to 40 minutes at a time. In some schools, classes begin in kindergarten and continue through 6th grade, while in other schools they begin in 2nd, 3rd, or 4th grade. The level of proficiency attained by the students is usually directly related to the amount of time they spend using the foreign language. Page 2 of 14 WHAT IS CONTENT-BASED FLES? Content-based, or content-enriched, FLES differs from regular FLES in that subject content from the regular school curriculum is taught in the foreign language, thus the focus is not on (explicit) language instruction alone. Teachers integrate content learning with language development via activities where the main topics come from the regular curriculum content areas (i.e., social studies, mathematics, science) so that language is acquired in a meaningful context. These content-based activities can provide a framework for developing higher cognitive skills as well as a vehicle for both language learning and content learning. Because they spend more time using the foreign language and are exposed to a wider variety of topics, students in content-based FLES programs generally attain a higher level of proficiency than their counterparts in regular FLES programs. WHAT IS FLEX? The goals of FLEX programs are to introduce students to a foreign language and culture, and to motivate them to pursue further language study. Unlike FLES classes, where all or most of the instruction is in the foreign language, FLEX classes are usually conducted in English, with some basic communication in the foreign language. Obviously, fluency in the foreign language is not an objective. In some cases, students are exposed to one language and culture for the duration of the school year, while in others, a sequence of two or three languages may be offered in the course of the year. Some elementary schools offer three one-year courses, each in a different language, during the last three years of elementary school, to help students decide which language to study in secondary school. The level of proficiency achieved is much lower than in FLES classes, but FLEX can serve a useful purpose by creating enthusiasm for language study in general. WHEN AND WHERE DO CLASSES MEET? In some schools, foreign languages are part of the regular school curriculum, and classes meet during the day. In other school districts, foreign language classes are sponsored by the PTA or by an independent group of parents, and while the classes are often held on school premises, they are obliged to meet before or after the regular school day. There are advantages and disadvantages to each situation. Classes that are part of the school day have little or no dropout problem and are legitimized by being part of the curriculum. Staffing is less of a problem as language teachers usually prefer to work during the regular school hours and be regular faculty members. Sometimes, however, schools find it difficult to fit foreign language classes into the already overflowing elementary curriculum. When classes meet before or after school, encroaching on the regular school day's time is not a problem, but these classes have to compete with other extra-curricular activities. It can be difficult to attract enough students to form a class. Staffing is more of a problem as it is often difficult to attract competent Page 3 of 14 teachers who can work the necessary hours, and who are willing to spend time traveling to and from schools to teach 30 minute classes. Some language teachers have their own classroom, while others travel from one class to another. Most teachers seem to prefer having their own room, as it enables them to create a special environment without invading the space of the regular classroom teachers who usually appreciate having a period of time to work alone in their room. HOW ARE FLES AND FLEX PROGRAMS STAFFED? The lack of availability of competent language teachers who have experience working with elementary school children is often a major problem. The criteria for good FLES teachers should include native or near-native fluency in the foreign language, an understanding of the culture(s) of or associated with the language, knowledge of second language learning processes and teaching methods, and experience working with young children. It is often difficult to find enough teachers who meet all these requirements, and schools sometimes have to train teachers who meet only some of the above criteria. These teachers include: a) elementary certified teachers who speak the target language, but are not trained to teach it, b) teachers certified to teach a foreign language at the secondary level but not to teach in an elementary school, and c) native speakers without teacher certification but with prior teaching experience. In addition, in FLEX classes, where exposure rather than proficiency is the goal, one can sometimes find elementary teachers who do not speak the foreign language learning the language along with the students. When recruiting teachers for a foreign language program, it is important to remember that the students will not be able to achieve a higher degree of fluency than their teacher (assuming that their exposure to the language is limited to the classroom). WHAT MATERIALS AND RESOURCES ARE AVAILABLE? Publishers of foreign language texts have begun to heed the growing need for FLES materials. Although most programs still rely on teacher-developed materials, some authentic materials can be obtained directly from foreign countries through personal contacts or travel, other materials can be borrowed from the regular classroom, and garage sales often prove to be a good source of toys, puppets, etc. For a comprehensive list of ideas for stocking the FLES classroom, see chapter 12 of Languages and Children - Making the Match by Curtain and Pesola. Conferences and workshops held by language teaching and advocacy organizations provide parents, teachers, and administrators with the means to stay abreast of new developments in the field. FLESNews, a newsletter published three times a year by the National Network for Early Language Learning, encourages the sharing of ideas, experiences, and information among FLES teachers. Many useful documents can be found through the ERIC system (available at Page 4 of 14 most libraries), and the ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics has produced a number of bibliographies and fact sheets on foreign languages in the elementary school. WHAT ARE THE HALLMARKS OF A SUCCESSFUL PROGRAM? Successful programs: - have community and administrative support; - are staffed by fully qualified teachers; - have well-planned curricula, designed to meet program goals; - have sufficient resources to carry out the program; and - maintain high student interest and measurable achievement. REFERENCES Anderson, H. & Rhodes, N. (1983). Immersion and other innovations in U.S. elementary schools. In: "Studies in Language Learning," v4 1983. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 278 237) Andrade, C. & Ging, D. (1988). "Urban FLES models: Progress and promise." Cincinnati, OH: Columbus, OH: Cincinnati Public Schools, Columbus Public Schools. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 292 337) Criminale, U. (1985). "Launching foreign language programs in elementary schools: Highpoints, headaches, and how to's." Oklahoma City, OK. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 255 039) Curtain, H. & Pesola, C.A. (1988). "Languages and children - Making the match. Foreign language instruction in the elementary school." Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Thayer, Y. (1988). "Getting started with French or Spanish in the elementary school: The cost in time and money." Radford, VA: Radford City Schools. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 294 450) The Wingspread Journal. (July 1988). "Foreign language instruction in the elementary schools." Racine, WI: The Johnson Foundation. Page 5 of 14 What does the Research Show? Annotated Bibliography Research in Support of Elementary School Foreign Language Learning SOURCE: http://www.yearoflanguages.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3653 American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages FLES (FOREIGN LANGUAGE IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL) PROGRAMS Andrade, C. et al. (1989). Two languages for all children: Expanding to low achievers and the handicapped. In K. E. Muller (Ed.), "Languages in elementary schools" (pp. 177-203). New York: The American Forum. Describes student performance in the Cincinnati Foreign Language Magnet Program. These children score well above anticipated national norms in both reading and mathematics and higher than the average of all magnet school participants, despite the fact that they represent a broad cross-section of the Cincinnati community. Armstrong, P.W., & Rogers, J.D. (1997). Basic skills revisited: The effects of foreign language instruction on reading, math and language arts. "Learning Languages, 2"(3), 20-31. Presents a study that provides quantitative and qualitative evidence of the effect of foreign language education upon the basic skills of elementary students, with the hope that such evidence will provide information and assistance to parents and educators who are investigating the benefits of elementary school foreign language programs. Bastian, T.R. (1980). "An investigation into the effects of second language learning on achievement in English." (pp. 6176-6177). DA, 40,12-A, Pt 1. Boise, ID: University of Idaho. Graduating high school seniors with two or more years of foreign language study showed significant superiority in performance on achievement tests in English when compared with non-foreign language students. Brega, E., & Newell, J.M. (1967). High-school performance of FLES and non-FLES students. "Modern Language Journal, 51," 408411. Compares performance of two groups of 11th grade students on MLA French examination (advanced form) in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. One group of students had begun French in Grade 7, the other group had also had 80 minutes per week of FLES beginning in Grade 3. FLES students outperformed non-FLES students in every area. Campbell, W.J. (1962). "Some effects of teaching foreign language in the elementary schools." NY Hicksville Public Schools.: Dec. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 013 022) Contrasts performance in all school subjects of FLES (20 minutes per day) and non-FLES students, all selected to have IQ of 120 or above. Data collected over 3 years suggests that FLES has a positive effect. Cohen, A. (1974). The Culver City Spanish immersion program: The first two years. "Modern Language Journal, 58"(3), 95-103. Demonstrates student progress in second language acquisition while maintaining par with English-speaking peers in math and other basic subjects. Page 6 of 14 Diaz, R.M. (1983). "The impact of second-language learning on the development of verbal and spatial abilities." DA, 43, 04-B, 1235. New Haven, CT: Yale University. Supports the claim that bilingualism fosters the development of verbal and spatial abilities. Donoghue, M.R. (1981). Recent research in FLES. "Hispania, 64," 602-604. Cites and summarizes basic research in FLES. Foster, K.M., & Reeves, C.K. (1989). FLES improves cognitive skills. "FLES News, 2"(3), 4. Describes the results of 1985 assessment of positive effects of Louisiana elementary school foreign language program upon basic skills acquisition. Garfinkel, A. & Tabor, K.E. (1991). Elementary school foreign languages and English reading achievement: A new view of the relationship. "Foreign Language Annals, 24," 375-382. Elementary school students of average academic ability showed improved reading achievement after participation in a voluntary before- and after-school FLES program. Horstmann, C.C. (1980). The effect of instruction in any of three second languages on the development of reading in Englishspeaking children. (p. 3840). DA, 40, 07-A. Compared reading scores in Cincinnati program among French, German, and Spanish learners in Grade 2 and a control group. There were no deficiencies; German group showed a significant positive difference over control group. Johnson, C.E., Flores, J.S., & Ellison, F.P. (1963). The effect of foreign language instruction on basic learning in elementary schools. "Modern Language Journal, 47," 8-11. Performance on Iowa Test of Basic Skills was compared for fourth-graders receiving 20 minutes per day of audiolingual Spanish instruction and similar students receiving no Spanish instruction. No significant loss in achievement in other subjects was found; the experimental group showed greater achievement in reading, vocabulary, and comprehension. Landry, R.G. (1974). A comparison of second language learners and monolinguals on divergent thinking tasks at the elementary school level. "Modern Language Journal, 58," 10-15. Divergent thinking ability was improved for FLES participants over non-FLES participants after 5 years of schooling, although no significant difference was found after 3 years of schooling. Lipton, G., Rhodes, N. & Curtain, H. (Eds.). (1985). "The many faces of foreign languages in the elementary school: FLES, FLEX, and immersion." Champaign, IL: American Association of Teachers of French. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 264 727). Describes FLEX program: 30 minutes per week, taught by volunteers in many languages, all grades. ITBS scores for participants were higher than those for nonparticipants. Lopata, E.W. (1963). FLES and academic achievement. "French Review, 36," 499-507. Classes of third-grade children in New York City and suburban New York schools were taught conversational French for 15 minutes daily. After 1 year they were evaluated for French skills, and their scores on the Stanford Achievement Test were compared with scores of children who had not received French instruction. All statistically significant differences were in favor of the experimental group, and seven of eight mean differences were in favor Page 7 of 14 of the experimental group. Children were judged to have pronunciation and fluency in French superior to that of high school students with the same amount of instruction. Masciantonio, R. (1977). Tangible benefits of the study of Latin: A review of research. "Foreign Language Annals, 10," 375-382. Examines linguistic benefits of Latin in building English vocabulary and reading skills, based on eight projects. Mavrogenes, N.A. (1979). Latin in the elementary school: A help for reading and language arts. "Phi Delta Kappan, 60," 675-77. Cites studies in several cities in which FLES students surpassed non-FLES students in test performances in reading and language arts. Washington study includes students in Spanish and French as well as Latin. Mayeux, A.P., & Dunlap, J.M. (1966). "French language achievement: The effect of early language instruction on subsequent achievement." University City, MO: University City School District. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 070 359). Addresses achievement in further study of the same language in Grade 7 (20 minutes per day) after 3 years of French FLES. Marked positive difference in achievement. Nespor, H.M. (1971). "The effect of foreign language learning on expressive productivity in native oral language." (p. 682). DA, 31 (02-A) University of California, Berkeley. Foreign language learning in Grade 3 is shown to increase expressive oral productivity in pupils' native languages. Peal, E., & Lambert, W.E. (1962). The Relationship of bilingualism to intelligence. "Psychological Monographs, 76"(27), 1-23. Monolingual and bilingual French-English children, aged 10, were administered verbal and nonverbal intelligence tests and measures of attitudes toward the English and French communities. Bilinguals performed significantly better on both verbal and nonverbal intelligence tests. Rafferty, E.A. (1986). "Second language study and basic skills in Louisiana." Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana Department of Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 283 360). Third, fourth, and fifth graders studying languages showed significantly higher scores on the 1985 Basic Skills Language Arts Test than a similar group of non-participants. In addition, by fifth grade the math scores of language students were also higher than those of non-language students. Samuels, D.D., & Griffore, R.J. (1979). The Plattsburgh French language immersion program: Its influence on intelligence and self-esteem. "Language Learning, 29," 45-52. Tested 6-year-olds after 1 year in French immersion with WISC and Purdue Self Concept Scale. No significant difference on Verbal IQ or PSCS; significant differences in favor of immersion students on Performance IQ, Picture Arrangement Object Assembly. Schinke-Llano, L. (1986). "Foreign language in the elementary school: State of the art." Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich. An examination of historical and contemporary issues surrounding FLES, emphasizing program design. Comprehensive bibliography. Vocolo, J.M. (1967). The effects of foreign language study in the elementary school upon achievement in the same foreign language in the high school. "Modern Language Journal, 51," 463-469. FLES students were found to have significantly better performance in listening, speaking, and writing when compared to non-FLES students at the end of an intermediate-level high school French class. Page 8 of 14 Yerxa, E. (1970). Attitude development in childhood education toward foreign people. "Journal of Education, 152"(3), 23-33. Review of theory and research on attitude development. Page 9 of 14 Characteristics of Effective Elementary School Foreign Language Programs SOURCE: http://www.yearoflanguages.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3655 American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages 1. Access and Equity All students, regardless of learning styles, achievement levels, race/ethnic origin, socioeconomic status, home language, or future academic goals, have opportunities for language study. 2. Program Goals and Program Intensity Program goals are consistent with the amount of time actually provided for instruction. The desired program outcomes determine time allocations for elementary school programs. There are three types of programs at the K-8 level: FLES (Foreign Language in the Elementary School) Immersion FLEX (Foreign Language Experience or Exploratory) These programs vary in levels of language proficiency to be achieved, amount of cultural knowledge to be gained, and time required to reach the program goals. FLES programs are designed to provide a sequential language learning experience aiming for some degree of language proficiency. Immersion programs combine foreign language instruction with content learning from the regular curriculum. FLEX programs are designed to provide limited exposure to one or more foreign languages for pre-secondary students. 3. Extended Sequence Elementary and middle/junior high school foreign language programs are the foundation for a long, well-articulated sequence of carefully developed curricula that extend through grade 12. Students in such programs can develop increased language proficiency and cultural competence. 4. Articulation Articulation of the extended sequence is both vertical and horizontal, including the elementary school, the middle/junior high school, and the high school. This articulation is the result of consensus, careful planning, and monitoring among language teachers, administrators, and parents at all levels. Students in these programs achieve outcomes that are consistent across grade levels. 5. Curriculum Human, fiscal and time resources are available for systematic curriculum development. The curriculum review cycle provides for assessment. 6. Instruction Instruction is appropriate to the developmental level of the students and consistent with program outcomes and current professional practices. 7. Materials Materials appropriate for students' developmental level, rich in authentic culture and language, and related to the curriculum are key components in elementary school foreign language programs. The main focus of all materials, both print and non-print, is the teaching of communication. 8. Evaluation Processes for evaluating both student achievement and program success are in use. Evaluation processes are appropriate to the goals, objectives, and teaching strategies of elementary school foreign language programs, as well as to the developmental level of children. 9. Staffing Programs are staffed by certified teachers who have completed preparation in methods and materials for elementary school foreign language instruction, developmental characteristics of the elementary school learner, and the nature of the elementary school curriculum. Modern foreign language teachers should have a high level of language and cultural competence. Based on the Page 10 of 14 ACTFL/ETS proficiency scale, a teacher's oral proficiency in a foreign language should be "Advanced." 10. Professional Development An ongoing program of professional development should allow teachers to advance in their levels of language, culture, and instruction. 11. School and Community Support and Development The foreign language teachers work with the entire school community to integrate the foreign language curriculum into the school educational program. The elementary school foreign language program shows responsibility for and makes effective use of parent and community resources and of school board and administrative staff. 12. Culture The connection between language and culture is made explicit, and foreign language instruction is implemented within a cultural context. Cultural awareness and understanding are explicit goals of the program. The program collaborates with other cultures and countries (exchange programs, pen pals, etc.) to assure language learning within a context of cultural experiences. Page 11 of 14 Guidelines for Starting an Elementary School Foreign Language Program By Marcia H. Rosenbusch, National K-12 Foreign Language Resource Center, Iowa State University ERIC Digest June 1995 In the past decade, schools have demonstrated increased interest in beginning the study of foreign languages in the early grades. Influencing this trend are a number of national reports urging that the study of languages other than English begin early (Met & Rhodes, 1990). Another influence on the trend toward an early start is research that indicates that the early study of a second language results in cognitive benefits, gains in academic achievement, and positive attitudes toward diversity (Rosenbusch, 1995). Perhaps the most important influence on early foreign language study will come from the national initiative, Goals 2000. In this initiative, foreign languages are designated as part of the core curriculum, together with traditional subject areas such as math, science, and social studies. As part of this initiative, the foreign language profession has developed national standards for foreign language programs beginning in kindergarten and continuing through 12th grade. Although these standards are not mandatory, they are certain to increase even further the interest in starting foreign language study in the early grades (Phillips & Draper, 1994). Cautions in Planning a Program Schools that are planning new elementary school foreign language programs need to be well informed about the factors that led to the disappearance of the popular elementary school foreign language programs of the 1950s and 1960s, because these factors continue to be a challenge to program viability today (Heining-Boynton, 1990; Lipton 1992). Such factors include the following: Lack of teachers with sufficient language skills and qualifications to teach a foreign language to young students. Programs inadequate in design and without the necessary funding. Inappropriate or unrealistic program goals. Lack of coordination and articulation across levels of instruction. Inappropriate teaching methodologies for young students. Inadequate and insufficient instructional materials. Lack of evaluation procedures for students, teachers, and the program. Initiating the Planning Process When a school has made the decision to explore the implementation of an elementary school foreign language program, the first step is to identify a steering committee to lead the process. This committee should include representatives of all those who have a stake in the implementation of a program: parents, foreign language teachers, classroom teachers and school administrators from both the elementary and secondary schools, district administrators, and business and community members. The steering committee must complete the following tasks: Research the rationale for an early start to the study of a foreign language in order to clarify the reasons for implementing an elementary school program. Examine the advantages and limitations of each program model by reading the professional literature (including results of research studies), consulting with language professionals, and visiting existing programs. Explore elementary school foreign language curricula and teaching strategies to define the nature of current foreign language instruction at the elementary school level. Explore models for articulating the foreign language program across levels (elementary, middle school, high school) to provide for an uninterrupted sequence of instruction that will result in higher levels of fluency in the language. Evaluate the school district's existing foreign language program so that future plans can build on current program strengths. Inform teachers and administrators, parents, and the community about the rationale for elementary school foreign language programs, strategies of teaching foreign languages at this level, program models and outcomes, and articulation models. Page 12 of 14 Explore school, parent, business, and community support for an elementary school foreign language program. Determine the most promising program model(s) for the local situation through discussion of the philosophy of the foreign language program and the desired program outcomes (Rosenbusch, 1991). Designing the Program Several components of the structure of the elementary school foreign language program must be considered with special care. These include: scheduling, curriculum design, instructional materials, staffing, multiple entry points, student accessibility, language choice, and program articulation, coordination, and evaluation (Curtain & Pesola, 1994; Met, 1985; Met, 1989; Rosenbusch, 1991). After researching the literature and through inquiry during school visitations, the steering committee should discuss each concern in depth before finalizing its recommendations. Information about each of the program components can be found in the references listed at the end of this paper. A key reference that will be extremely useful to the committee is "Languages and Children: Making the Match" (Curtain & Pesola, 1994). Two of the most challenging aspects are discussed briefly here. "Scheduling." The minimum amount of time recommended for an elementary school foreign language class is 75 minutes per week, with classes meeting at least every other day (Rosenbusch, 1992). Met and Rhodes (1990) suggest that "foreign language instruction should be scheduled daily, and for no less than 30 minutes" (p. 438) to provide periods that are long enough for activities, that are motivating to the students, and to prevent teacher burnout. "Language Choice." Determining which languages will be taught is potentially the most controversial issue in program design (Met, 1989). Some experts recommend that this decision be the last one made in order to keep the issue from becoming divisive. As the decision is made, the following considerations should be kept in mind: teacher availability, program organization and scheduling, maintenance of established upper level language programs, and language diversity (Curtain & Pesola, 1994). Programs That Lead to High Levels of Fluency If the steering committee determines that the central goal of the district's program is that students attain a high level of fluency in the foreign language, the committee will choose the earliest possible start for the study of the language, maximize the time and intensity of the program at every level, and provide an articulated program that flows across levels without interruption. Students will be able to continue their study of the language throughout every level and will have the opportunity to add a second language or change languages at the beginning of middle or high school. All students will study a foreign language "regardless of learning style, achievement level, race/ethnic origin, socioeconomic status, home language, or future academic goals" (Met & Rhodes, 1990, p. 438). The teachers involved in the program at all levels will have excellent language skills, be well informed about current teaching strategies, and work together as a team to provide a carefully developed, articulated curriculum. Determining Program Feasibility The steering committee should examine the feasibility of the most promising program model(s) for the local situation with the help of school administrators who determine budget, scheduling, and space usage, and who make personnel decisions. Based on their previous study and the feasibility information, the steering committee will determine what recommendation it will make to school administrators and the school board concerning the start-up of an elementary school foreign language program (Rosenbusch, 1991). This final decision may be a difficult one to make. If the district is not willing to make a serious commitment to developing a strong foreign language program, the steering committee must be ready to recommend that no elementary school program be established at the present time. Experience demonstrates that it is difficult to change a weak program design for a strong one once a program has been established. A weak program design will not allow students to develop high levels of proficiency in the language. If adequate support for a program is lacking, effort may be better spent in solving the problems that prevent the establishment of a quality program and in working to build support by educating the community about the nature and value of strong foreign language programs. Met and Rhodes (1990) clarify that "a primary goal in the next decade is to work actively to increase the number of high-quality, carefully designed elementary-school foreign language programs based on strong administrative, parental, and community support" (p. 438). The implementation of elementary school foreign language programs of excellence is critical to the development of the foreign language proficiency skills our nation's students will need in the future. Page 13 of 14 References Curtain, H., & Pesola, C.A. (1994). "Languages and childen: Making the match" (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman. Heining-Boynton, A. (1990). Using FLES history to plan for the present and future. "Foreign Language Annals, 23," 503-509. Lipton, G. C. (1992). "Practical handbook for elementary language programs" (2nd ed.). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook. Met, M. (1985). Decisions! Decisions! Decisions! "Foreign Language Annals, 18," 469-473. Met, M. (1989). Which foreign language should students learn? "Educational Leadership, 7," 54-58. Met, M., & Rhodes, N. (1990). Priority: Instruction. Elementary school foreign language instruction: Priorities for the 1990s. "Foreign Language Annals, 23," 433-443. Phillips, J., & Draper, J. (1994). National standards and assessments: What does it mean for the study of second languages in the schools? In G.K. Crouse (Ed.), "Meeting new challenges in the foreign language classroom" (pp. 1-8). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook. Rosenbusch, M. (1991). Elementary school foreign language: The establishment and maintenance of strong programs. "Foreign Language Annals, 24," 297-314. Rosenbusch, M., Ed. (1992). "Colloquium on Foreign Languages in the Elementary School Curriculum. Proceedings 1991." Munich: Goethe Institut. (Available from AATG, 112 Haddontowne Ct., #112, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034) Rosenbusch, M. (1995). Language learners in the elementary school: Investing in the future. In R. Donato & R. Terry (Eds.), "Foreign language learning, the journey of a lifetime." Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook. Page 14 of 14