Sexual pleasure only in the north - Bridge

advertisement

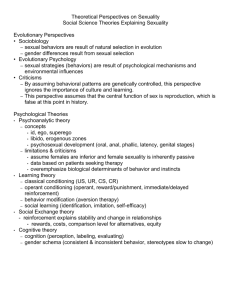

Gender Myths and Feminist Fables: Repositioning Gender in Development Policy and Practice Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex 2-4 July 2003 Susie Jolly, BRIDGE, IDS ‘Development Myths Around Sex and Sexualities in the South’1 June 2003 1 Paper prepared for the International Workshop Feminist Fables and Gender Myths: Repositioning Gender in Development Policy and Practice, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, 2-4 July 2003. 1 Mohanty (1991) argues that western feminist research imposes its own cultural viewpoint on third world women. Blinded by colonial preconceptions, these researchers are unable to see the realities of the people they study. Mohanty looks at representations of ‘third world women’ in a series of writings by ‘first world’ feminists on subjects such as female genital mutilation and women in development. The texts she considers consistently define women as objects of what is done to them, rather than as actors with any agency, and as victims of either ‘male violence’, ‘the colonial process’, ‘the Arab familial system’, ‘the economic development process’, or ‘the Islamic code’. Such research, she states, ‘colonise[s] the material and historical heterogeneities of the lives of women in the third world’ to construct a singular image of ‘an “average third world woman”…[who] leads an essentially truncated life based on her feminine gender (read: sexually constrained) and her being “third world” (read: ignorant, poor, uneducated, tradition-bound, domestic, family oriented, victimized etc.), in contrast to the liberated western woman’ (p 56). Mohanty recognises how this homogenising includes sexuality, erasing ‘all marginal and resistant modes and experiences. It is significant that none of the texts I reviewed in the … series focuses on lesbian politics or the politics of ethnic and religious marginal organizations in third world women’s groups’ (Mohanty 1991:73). Development discourses perpetuate such limited views of sexualities in the south. Sexuality is usually ignored, or discussed only in terms of risk disease, violence, reproductive decision making, or material and social considerations. Southern women and men are represented as homogenous and clear cut categories, with a uniform heterosexual sexuality in which reproduction or disease are the key issues. Love, desire and sexual pleasure are usually absent in development representations of sex and sexuality in the south (Gosine 1998). For example, Caldwell et al (1989) argue that there is a system of African sexuality ‘distinct’ from the west, characterised by greater commercial exchange, and particularly in west Africa, a lack of evidence of female enjoyment. Such views on sexuality are starting to be challenged in the development arena due to both HIV/AIDS and human rights approaches. With HIV/AIDS, there is increasing recognition of the impact of sexuality on health, survival and poverty. Discussions around sex and power, including within marriage are opening up and this is becoming a legitimate area for development intervention (Cornwall and Welbourne 2002). At the same time, international support on a small scale is being made available to those with marginalised gender identities and sexualities, particularly men who have sex with men. In international and development arenas, it is being asserted that human rights include rights of sexual minorities. In April this year Brazil presented a draft resolution to the UN Commission on Human Rights, co-sponsored by over 20 countries, which expressed ‘deep concern at the 2 occurrence of violations of human rights all over the world against persons on grounds of their sexual orientation’ (Amnesty International 2003). Although scuppered by opposition from Muslim states and the Vatican, the presentation of this resolution in itself marks new openings for discussion of sexuality in such fora. Nevertheless, rising conservatism limits development action around sexuality, for example recent USAID prohibitions on support to homosexual or abortion related organisations. And while the subject is now entering development discourse, sexuality is usually constructed as being about violence and rights, and not about pleasure (Miller 2000). Mohanty holds that her critique can also apply to third world scholars who set up their own standards as the yardstick by which to encode and create cultural others. She also maintains that westerners can avoid falling into this trap by focusing on local particularities and deconstructing rather than starting from colonial preconceptions. I will attempt to follow Mohanty’s suggestion by deconstructing the development myths of southern sexualities being homogenous, exclusively heterosexual, based on clear cut gender identities, and about reproduction and material/social interests rather than pleasure. I do this through drawing together case studies which illustrate the diversity of sex and sexuality and the importance of pleasure in sexuality in southern contexts. Myth 1: Homosexuality is a western privilege The poor simply can’t be queer, because sexual identities are seen as a rather unfortunate result of western development and are linked to being rich and privileged. The poor just reproduce (Kleitz 2000:2) Numerous examples of organising around same-sex sexualities and transgender identities in Asia (IIAS 2002), Africa (Murray and Roscoe 1998, Khaxas 2001), and Latin America (Drucker 2000) put a lie to the myth of homosexuality being western. Furthermore, some poor do have same sex sexualities, and indeed violence, discrimination and social exclusion inflicted on those with marginalised sexualities can result in poverty as has been recorded in Sri Lanka (Miller 2002), Britain (Albert Kennedy Trust 2003) and Bangladesh (Bandhu study cited in Naz foundation 2002). Findings of the Bandhu study are presented in the box below. Key Findings of Bandhu Study on Men Who Have Sex With Men in Bangladesh (MSM) Of 124 MSM interviewed for the Bandhu Study, 56% have a monthly income of Taka 1000 to 3000 (US$ 0.60-1.70 per day). Only 8% of the respondents earned more than Taka 5000 a month (US$ 2.80 per day). 3 64% reported facing harassment of one kind or the other at the hands of the police. 48% reported that they have been sexually assaulted or raped by policemen. 65% have reported that they have been sexually assaulted or raped by mastaans (“thugs”). 71% of the total respondents stated that they had faced some or the other form of harassment from mastaans. Other than rape, these are, extortion [38%], beatings [45%], threats and blackmail [31%]. Kothis (Feminine men) have low levels of education and literacy, with high early drop out rates from school due to harassment and bullying (Adapted from Gosine, forthcoming) Keith Goddard, programme officer in Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe (GALZ), describes how gay people in Zimbabwe are thrown out of their jobs and families as a result of their sexuality. In response, one of GALZ’ main activities consists of support for homeless gays and lesbians, and providing a ‘skills for life’ programme aiming to help members enter formal employment. Myth 2: We are all either women or men Sex marks the distinction between women and men as a result of the biological, physical and genetic differences between them. Gender roles are set by convention and other social, economic, political and cultural forces (One World Action Leaflet 2002) In GAD discussions gender is still often described as socially constructed, and sex as biological. The categorising of all human beings as 'male' or 'female' is left unquestioned. However, this does not always fit with local realities. Throughout South Asia, communities of ‘hijras’ are formed by intersex people, and by transgender people who were born male, but do not identify as such, many of whom opt for castration2. It has been estimated that there are a half to one million hijras in India alone (Bondyopadhay 2002). Traditionally and today, hijras are channelled into sex work and entertaining. Cultures of hijras in South Asia, travestis in Brazil, ladyboys in Thailand, or transgender in the USA all suggest that there is more to sex than just male and female. Perhaps ideas of sex are socially constructed too. 2 Intersex refers to those whose chromosomes or anatomy does not perfectly match the criteria for male or female. Up to one in every five hundred babies are born intersex (Philips 2001:31). ‘Transgender’ refers to all those who do not feel they fit sex norms, including those who feel their bodies do not match the sex they feel themselves to be, and those who do not feel they are either male or female, or reject the requirement to conform to these categories. 4 Hijra organising in Bangladesh In Bangladesh in 2000, a group of hijras, most of whom are sex workers, formed Bondhon, (‘bond’ in Bengali). This organisation engages in a range of activities including HIV/AIDS prevention work, supported by international funding, and campaigning for the human rights of sex workers. They are also allying with other organisations in a lobby for inclusion of the identity intersex on voter identity cards for future elections, which presently specify the voter must be either male or female. At the same time as campaigning for recognition as intersexuals, Bondhon is reaching out to the national women’s network Doorbar (‘indomitable’ in Bengali). This dual strategy may reflect the diversity within Bondhon, where most members identify as female, but some identify as neither male nor female, or as both. Doorbar member organisations, many of whom are grassroots rural women’s groups started a process of discussion on the relationship with Bondhon. This discussion raised new issues of gender, sex and sexuality, and provoked a range of reactions. Some were curious or suspicious. Others were welcoming, and felt if Bondhon members identify as women, then they qualify for inclusion in Doorbar. A process of exchange between Doorbar and Bondhon began, resulting in Bondhon being finally accepted as a Doorbar member organisation. Interview with Shireen Huq at the Institute of Development Studies, 8th July, 2002 Myth 3: Sexual pleasure – nothing to do with development We are told that sex between white people is about desire, love, romance and pleasure, and that sex between non-white people is about reproduction, fertility control, stupidity and misery (Gosine 1998:5) In colonial times and even today, the sexualities of people living in developing countries have been stereotyped as exotic, mysterious, or uncivilised. Development discourses however have adopted the flip-side of this stereotype, either ignoring sexuality, or including it only in relation to (over) population or disease and violence. Gosine (1998) identifies a ‘racialization of sex’ in both development discourse and western popular culture, where positive sensual and emotional aspects of sex are represented for white people in the north, but denied for people in the south where population and disease are taken to be the primary concerns. This myth has been contested by organising around sexual pleasure, as an empowerment tool, as a means to counteract HIV/AIDS, or as a human right in itself. Examples are presented below which illustrate the need for development activities to engage with this issue. 5 Pleasure in sex work in China In a focus group discussion with sex workers taking part in a DFID 3 HIV/AIDS project in china, several sex workers said they had enjoyed sex with clients who were cute, clean, polite or ‘high quality’, and some said they had orgasms. It was more likely to be enjoyable if they were using condoms, as they were more relaxed and not afraid of getting a disease. They also said many clients asked them if they enjoyed it (shufu ma?) to which they always replied yes, regardless. This indicates that even within the sex worker – client relationship, there is potential for the sex worker to get pleasure, and that some clients at least act as if they hoped they gave pleasure. Sex workers said one of the most effective strategies to encourage clients to use condoms, which was taught in the DFID training they took part in, was to put these on with their mouths, as clients enjoyed this and were subsequently less aware of the condom being on. However, in much of the implementation of the DFID-China programme, pleasure was ignored. Nevertheless, some programme strategies did link safer sex with pleasure, for example a magazine targeted at sex workers which featured a quiz entitled ‘Are you prepared for a safe sex life?’ which included questions such as ‘Can I let my sexual partner know what kind of touching I like, and where I like to be touched? Can I experience sexual pleasure without using drugs or alcohol?’ (Jolly and Wang 2003) 3 DFID – the UK Department for International Development 6 Sexual Pleasure as a Human Right: Experiences from a Grassroots Training Program in Turkey Women for Women’s Human Rights in Turkey talks about sexuality in terms of human rights as part of its programme on ‘Human Rights and Legal Literacy Training for Women’. This is conducted by specially trained social workers at Community Centres and State Residences for girls throughout Turkey. Included in the human rights training is a module which challenges the ideas that women are not permitted sexual pleasure and that sexuality should always be seen in terms of reproduction. Placing sexuality in a training programme that addresses a wide range of human rights issues brings it into a social rather than a private context. The subject of sexuality is broached at the end of the training when the concepts of human rights and how to claim them are understood, and when participants are already familiar with each other. A strong emphasis is placed on building up an environment of security and trust in the workshops. Women who attended the sessions described how they had been chastised for being curious about sexuality when they were children, and had been totally ignorant about sexuality, virginity, pregnancy and their own (and their husband’s) bodies. During the session on sexual pleasure, the women were encouraged to see sexual pleasure as natural, and to separate sexuality from the negative ideas and experiences of violence, fear and shame that so often accompany these discussions. Women began to discuss their expectations of sex, and how they could sometimes talk about it with their friends despite the taboos. Some described how, even in poverty, sex is one of the few free enjoyments! The sessions were useful both for older women coming to terms with decades of negative feelings about sexual pleasure, and young women who were not yet sexually active. They also helped mothers to think about how they could better help their daughters understand sex and sexuality. Methods used in the training are: Opening the session by identifying positive and negative associations women have of sexuality, and showing how these are constructed; discussions around social myths and how these affect personal experiences; information sessions on the female sexual organs; and sharing of ideas on how to look at sexual pleasure in terms of human rights (Ilkkaracan et al 2000). 7 Sexuality and disability in Nicaragua The ‘Women with Disabilities program’ of the Nicaraguan NGO Solidez initially focused on organising self-help groups and providing economic support. However, programme participants demanded a broader programme. In response Solidez reoriented their strategy to explicitly address issues of ‘gender, self-esteem and reinforcing of women’s individual identities’ (Dixon 2001:11). With this goal in mind they ran gender training workshops on : Sex and gender identity (including the image of women) The basis of oppression Sexuality, pleasure and life stages Violence within families and within couples Sessions on sexuality broke taboos, allowing open discussion. Some women subsequently became involved for the first time in sexual and intimate relationships. For some this was experienced as positive, while for others this meant experiencing further discrimination in new areas (Dixon 2001). Concluding thoughts The initiatives presented in this paper illustrate the diversity of sex and sexualities, and that sexual pleasure is part of the story and can even be considered a human right by some organisations in the south. Sexuality can be an issue of survival and poverty, as illustrated by the Bandhu study on MSM in Bangladesh and by GALZ’ experience in Zimbabwe supporting people who lose their jobs or family due to their sexuality. Sex identities of ‘woman’ and ‘man’ exclude many people as testified by hijra organising in Bangladesh. Opening discussion on sexual pleasure is likely to be an effective strategy for promoting safer sex, addressing one of the reasons often given by women and men for not using condoms (eg. decrease in sensation). Focussing on both women’s and men’s pleasure can challenge gender norms that give priority to men’s pleasure and label women who enjoy sex as problematic. This can in turn open possibilities for negotiation of safer sex. Scare tactics which only emphasise risks have been shown to be ineffective in changing behaviour, scaring people into passivity, rather than supporting their ability to take control and make safer choices around their own desires (Tolman 2002). A happy healthy sexuality is one aspect of well-being, autonomy and can be considered a human right in itself as testified by the training programme by Women for Women’s Human Rights in Turkey. 8 These examples demonstrate the need for development actors to listen to and engage with diverse views on sex and sexuality rather than assuming sexuality is not an issue or imposing their own preconceived model. 9 Bibliography This paper draws on, and adapts sections from, Jolly, S., 2002, Gender and Cultural Change, BRIDGE Cutting Edge Pack series on topical gender themes, IDS, available on http://www.ids.ac.uk/bridge/reports_gend_CEP.html Albert Kennedy Trust, helping homeless lesbian and gay teenagers in the UK, http://www.akt.org.uk/, accessed 25 June 2003 Amnesty International press release, April 25th 2003 ‘UN resolution on sexual orientation’ Bondyopadhay, A., 2002, statement to UN Commission on Human Rights, April 18 2002, www.iglhrc.org, accessed June 2002 Caldwell, J.C., and Quiggin, P., 1989, ‘The social context of Aids in Sub-Saharan Africa, Population and Development Review, Vol. 15, no. 2:185-233 Cornwall, A. and Welbourn, A., 2002, Realizing Rights: transforming approaches to sexual and reproductive well-being, London and New York: Zed Books Dixon, H., 2001, Learning from experience: Strengthening organisations of women with disabilities, Solidez, Nicaragua, London: One World Action Drucker, P. (ed), 2000, Different Rainbows, London: Gay Men’s Press Fried, S., 2002, Annotated Bibliography: Sexuality and Human Rights, New York: International Women’s Health Coalition, available on www.siyanda.org Gosine, A., forthcoming 2003, Outsiders In? Sexual minorities in participatory development, IDS paper Gosine, A., 1998, All the wrong places: looking for love in third world poverty (notes on the racialisation of sex), Unpublished MPhil thesis, IDS Hartmann, B., 1995, Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population control, Boston, MA: South End Press 10 Huq, Shireen, interview by Susie Jolly with Shireen Huq at the Institute of Development Studies, 8th July, 2002 IIAS (International Institute for Asian Studies), 2002, ‘Asian homosexualities’, in IIAS Newsletter, no. 29, 14 June: 6-14 Ilkkaracan, Ipek and Seral, Gülsah, 2000, ‘Sexual Pleasure as a Women’s Human Right: Experiences from a Grassroots Training Program in Turkey’, in Pinar Ilkkaracan (ed.) Women and Sexuality in Muslim Societies, Istanbul: Women for Women’s Human Rights (WWHR): 187-196 Jolly, S. and Wang, Y., 2003, Gender Mainstreaming Strategy for the China-UK HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Project, Report for the Department for International Development (DFID), UK, available on www.siyanda.org Khaxas, Elisabeth, 2001, ‘Organising for sexual rights: The Namibian women’s manifesto’ pp. 6065 in Cynthia Meillon with Charlotte Bunch (eds) Holding on to the Promise: Women’s Human Rights and the Beijing+5 Review, New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Women’s Global Leadership, Rutgers Kempadoo, K., and Doezema, J. (eds), 1998, Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance and Redefinition, London: Routledge Kleitz, G., 2000, ‘Why is development work so straight?’, paper for the IDS seminar series Queering Development: challenging dominant models of sexuality in development, available on http://www.ids.ac.uk/ids/pvty/qd/qd.html Lind, Amy and Share, Jessica, ‘Queering Development: Institutionalised Heterosexuality in Development Theory, Practice and Politics in Latin America’ in Bhavnani, Kum-Kum, Foran, John, and Kurian, Priya, 2003, Feminist Futures: Re-imagining Women, Culture and Development, London, New York: Zed Books Miller, J., 2002, ‘Violence and Coercion in Sri Lanka’s Commercial Sex Industry: Intersections of Gender, Sexuality, Culture and the Law’ in Violence Against Women, 8(9): 1045-1074 Miller, A.M., 2000, ‘Sexual but not reproductive: exploring the junctions and disjunctions of sexual and reproductive rights’, Health and Human Rights, Vol. 4, No. 2: 68-109 11 Naz Foundation, 2002, Strategy Paper No. 7 Philips, H., 2001, ‘Boy Meets Girl’ in ‘Gender: Why two sexes are not enough’, New Scientist, No. 2290, 12 May 2001 Mohanty, C.T., 1991, ‘Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourse’, in C. Mohanty, A. Russo and L. Torres (eds) Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, Bloomington: Indiana University Press Murray, S. and Roscoe, W. (ed.), 1998, Boy wives and female husbands: Studies of African homosexualities, Macmillan: London Spronk, R., 2003, ‘Going Beyond the Stereotype of the “Pleasure-less African Woman”’, paper for the EADI Gender and Development Working Group Workshop on Sexuality, Gender and Development – A Feminist Challenge to Policy and Research, ISS, The Hague, 20-22 March 2003 Tolman, D.L., 2002, Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage Girls Talk about Sexuality, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press Wieringa, S., ‘HIV/AIDS and Women’s Sexual Empowerment in Indonesia’, paper for the EADI Gender and Development Working Group Workshop on Sexuality, Gender and Development – A Feminist Challenge to Policy and Research, ISS, The Hague, 20-22 March 2003 12