Optimization and Benchmarking of an

advertisement

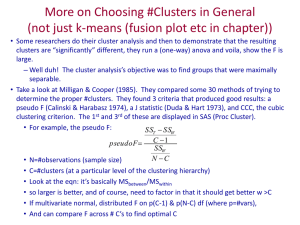

Optimization and Benchmarking of an EST Clustering Tool Kevin Pedretti Honors Project, Fall 1999 Introduction Clustering is the process of taking a set of elements and segmenting it into meaningful groups. As a very simple example, consider the task of partitioning 100 marbles into groups based on exact color. The result would be one group, or cluster, for each color of marble. If all the marbles were the same color, there would be one large cluster of 100 marbles. Conversely, if all the marbles were different colors then there would be 100 clusters, each one representing a single marble. For a random mix of marbles, the result would probably be somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. If the criterion for cluster membership was changed to be based on a shade range for each color (i.e. shades of blue, shades of red, etc.) the result of clustering would probably contain fewer but larger clusters. This is because multiple clusters under the old scheme would fall into a single cluster based on the new less stringent shade-range criterion. For the clustering described in this report, genetic sequences are the elements being clustered and the homogeneity criterion is sequence similarity. It is analogous to the simple marble example, however, the problem is much larger, both in the number of input elements and in the complexity of the similarity calculation. The specific type of sequence that clustering has been used for at the University of Iowa is called an EST, or Expressed Sequence Tag. This type of sequence comes from cDNA, which means that most of the sequence regions that don’t code for a protein have been removed by the processing that takes place inside of a cell. In addition, data generated at the University of Iowa has the property that sequencing of a given EST is always started from approximately the same base position. This anchoring makes it particularly easy to efficiently identify redundancy. However, the clustering program discussed in this paper also works for sequence data without this property. It is also generalizable to other types of nucleotide sequences besides ESTs. Clustering is useful for a number of reasons including: 1) To Assess Novelty Given a set of sequences, how many form clusters of size 1. The sequence in such a cluster is unique with respect to the input data set. Overall Novelty # single sequence clusters total # sequences 2) Avoid Duplication of Work Sequencing is costly. By identifying clusters, redundant sequence can be eliminated and the cost of unnecessary processing can be avoided. 3) Identify Gene Families Group together sequences that come from similar but different genes. This is the case when two genes are derived from the same ancestor gene. 4) Sequence Assembly Clustering can be used as a preprocessing step to sequence assembly to eliminate noise. Assembly programs take many short sequences as input and search for overlapping regions to form larger consensus sequences. This is necessary because current technology limits the length of a physically read sequence to around 700 bases. By grouping similar sequences together before processing, a better assembly can result. The original clustering program (uicluster) was written by Professor Thomas Casavant of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Iowa, in 1997. Since its creation, it has been used in the production pipelines of several high-throughput sequencing projects that are underway at the University of Iowa. With the original version of the clustering program, the time required to cluster the large amounts of data generated by these projects was significant and doing so on a regular basis became impractical. This report describes performance optimization and benchmarking of the clustering program done by Kevin Pedretti as an honors project for an undergraduate degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering. The changes are included in the version 2.0 release of the package. In addition, a graphical JAVA cluster viewer was developed as part of the project to make it easier to interpret the output of uicluster. Background Figure 1 shows what a typical sequence as input to clustering looks like. The average length of an EST sequenced at the University of Iowa is around 400 bases. The first line is the name of the sequence and the remaining lines are the sequence itself. Valid letters for the sequence portion are A, C, T, G, X, and N. The first four letters represent the 4 bases of DNA: Adenine, Cytosine, Thymine, and Guanine. X's are used to signify regions of low-complexity that are masked out in a preprocessing step. An example of a low-complexity region would be a run of 20 A's. It could also be a region that is repeated many times throughout the genome. If such regions were not masked out, the comparison stage of clustering might cluster together two sequences based on the similarity of a repetitive region even though the sequences are actually very different overall. Such occurrences are called false positives. Finally, the letter N is used to explicitly denote the unknown. The sequencing procedure is error-prone and sometimes it is impossible to say with confidence what base a particular position is or if one even exists at all. Thus, an N could mean that the position it represents is missing, inserted, or unknown. There are likely be errors in a sequence that aren't represented by N's they are only used when an error is obvious. >UI-R-A0-ae-b-09-0-UI TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGATTTTCAATGATAAACTTTTATTCTGAATATACTGTTTTTGCACAAGATTTA ACACAACATTTTCTGGGXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXCAAAATGTGTTCA TCCGACTAGTTAATTTCCACAAAAGTGTCCAGAGAACATAATAAGGGGGAGAAAAAAAATCTGTTGTTCA CAAAAGCCACTTGGCGTTTTGCTTGATGCACAATGAGCATTTCATGAAGAGAATCCCTAAAACATGATCC CACAGTCATACCGCACAAGGAAAGAACAGCTTGGCCAGGTCACATTGGAAACTCAATTGGCATTTACACC GGACAGCATGCCAGGAGTCTCAGTGGAATTTCCATGGTTCTTTTTTGTGTGAACTAGAAACAAGGTATAC GAAACCTCCCGTAACAGCAATCTATTTCTGCAAAATTCTGGCCATTTTCATGACCTGATAGTTCTGTTTT AGTGATTTGCTCTTTACAGAAATATACACCAGATAGTGACCATATCAACATTCTGCCATGGAGAACAATG CAAGTTCCAGCGAATGATAAAATAA FIGURE 1 A time consuming task that clustering must perform is sequence comparison. In the context of clustering, the result of a sequence comparison is binary either the two sequences are similar and belong in the same cluster or they don't. The criteria currently used for the EST data generated at the University of Iowa requires at least one window of 38 out of 40 matching bases for a positive result. The two allowed errors could be any combination of base insertion, base deletion, or base mismatch. Allowing for insertions and deletions means that the comparison operation is not a simple string comparison. The comparison routine is implemented as a recursive function that tests each of the three possible path branches whenever an error is encountered. This is not a trivial operation and in version 1.0 profiling showed that approximately 85% of the programs execution time was spent doing comparisons. Thus, the major optimizations in 2.0 seek to reduce the total number of comparisons performed. There are many approaches that could be used for clustering. One straight-forward protocol would be to compare each sequence to every other sequence and form a graph of significant matches. The clusters would then be formed by looking for disconnected regions in the graph. Figure 2 illustrates this approach. The problem with this method is that the number of sequence comparisons required is proportional to n2, where n is the number if sequences being clustered. Since sequences comparison is the most time consuming step of clustering, this O(n2) constraint severely limits the problem size that can be completed in a reasonable amount of time. N by N Clustering Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Cluster 1 Cluster 4 Sequence Significant Match FIGURE 2 The approach taken by uicluster avoids this problem by only comparing an input sequence against a single representative from each cluster (the cluster primary). For example, for a cluster containing 10,000 sequences, only 1 comparison would be performed for each input sequence vs. 10K with the n^2 approach. The drawback to this method is that the cluster representative doesn't necessarily represent all of the sequence data in the cluster. In the current version of clustering, the cluster representative is simply chosen to be the longest sequence in the cluster. Thus, there is a potential to miss some valid matches due to sequence data being “hidden” in a cluster. With ESTs this isn’t a large problem because of the anchoring property described in the introduction. A better method, and one proposed for the future, would be to assemble all the members of a cluster into a "master" consensus sequence that better represents all of the sequence data in the cluster. The figure 3 shows the basic clustering algorithm. There are many other features and optimizations present in the actual program that are left out here for clarity. Read 1 sequence at a time from input file Compare input sequence against all cluster representatives (or cluster primaries) If a “good’ match is found, add the input sequence to the cluster (it becomes a secondary member of the cluster) Otherwise, the input sequence becomes the representative of a new cluster FIGURE 3 Optimization Version 1.0 of uicluster used a hashing technique to speed up individual sequence comparisons. Figure 4 shows how the hashes are calculated. For each eight base window, a unique integer (referred to as a hash) is generated. For the first eight base region, ‘GCCACTTG’, the hash generated is 38014. The next window starts one position to the right and gets a hash of 20986. In this way, a hash is generated for each base position of a sequence (except for the seven bases before a masked out region, a letter N, or the end of a sequence). The mapping is exact so that any given integer exactly represents a sequential combination of eight bases. The reason for this step is that it is much faster to compare two integers than it is to compare eight characters. A sequence comparison is only initiated if two hashes match between a pair of sequences. While this approach greatly speeds up each sequence comparison, it does nothing to reduce the total number of comparisons performed for the clustering of a given data set. Sequence: GCCACTTGGCGTTTTG Hashes: Hash 1: GCCACTTG Hash 2: CCACTTGG Hash 3: CACTTGGC Hash 4: ACTTGGCG Hash 5: CTTGGCGT ...etc. = = = = = 38014 20986 18409 2022 32411 FIGURE 4 One of the major optimizations in version 2.0 uses the same hashing technique but seeks to eliminate the total number of sequence comparisons by memorizing the hashes of each cluster representative in a large table. Figure 5 shows the structure of this global hash table in detail. The table is a linear array of pointers with one element for each of the possible 48 hash values. Cascaded off each element in this array is a linked list of cluster representatives that contain at least one occurrence of the hash value that is the index into the array. This table is consulted for each input sequence and only the cluster representatives that have a strong potential for a “good” match are examined with the slow recursive comparison routine. The example in figure 5 shows that there are three cluster representatives that contain a region corresponding to a hash value of 2. Therefore, if an input sequence contains the hash value 2 then these three cluster representatives should be examined. Global Hash Table 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 48 - 1 Cluster Representative Sequence Name Sequence Hashes Hash Indexes Touch Count ... Linked list of clusters that contain at least 1 hash with value 2. Pointer To Next Cluster Member FIGURE 5 A further optimization is to only compare against cluster representatives that an input sequence hits N multiple times in the table. For the 38/40 matching base criterion, at least 16 hashes have to be in common between sequences in order for a match to even be possible. Thus, the global hash table can be used to identify only the cluster representatives that have 16 or more hashes in common with the input sequence. As the graphs in the results section below show, this modification greatly speeds up the clustering process. If a threshold higher than 16 were used then some valid short matches might be missed (false negatives). Results Figure 6 shows the effect of using different thresholds for the number of hash “hits” necessary to do a full comparison. As the threshold increases from 0 to 16, the number of comparisons performed drops more than two orders of magnitude for both of the two data sets shown. For the more novel data set (62%), the number of comparisons is nearly an order of magnitude greater than the less novel set (24%) at a threshold of zero. This is because there are be many more cluster representatives to compare against in a highly novel data set. However, when the threshold is increased to 16, the number of comparisons performed for each data set is nearly identical. This shows how the use of an appropriate threshold can filter out a large proportion of the unsuccessful comparisons. As mentioned earlier, care needs to be taken to keep the threshold small enough to avoid false negatives. For these two data sets, this was observed for thresholds above 20. Number of Potential Hits Examined for Different Threshold Values 1.E+08 1.E+07 # Hits Examined 10096 Sequences 6782 Clusters Novelty = 67% 1.E+06 10096 Sequences 2397 Clusters Novelty = 24% 1.E+05 Start to miss good hits. (False Negatives) 1.E+04 1.E+03 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 Threshold (Number of word hits necessary to do a full comparison) FIGURE 6 Figure 7 compares the execution times of version 1.0 and 2.0 of uicluster. The data set clustered is the entire set of rat EST sequences produced at the University of Iowa over the past two years. This data set is continuously growing and the current processing protocol is to cluster the entire set on a weekly basis. In addition to rat, there are several other organism data sets that are clustered each week. The optimizations in version 2.0 clearly produce a considerable time savings for this operation and the time gap will continue to grow as more sequences are added to the data sets. The small difference in the clustering resulting from the two versions is small enough to not be significant. It’s likely a result of the minor difference in the sequence comparison routines of the two versions. New vs. Original Execution Time Dataset: UI RatEST Data (80766 sequences, 3*10^7 bases) 60000 Original ~14 Hours 33340 Clusters 41.26% Novelty 50000 Time (seconds) 40000 30000 New ~30 Minutes 33340 Clusters 41.28% Novelty 20000 10000 0 10096 20192 30288 40384 50480 60576 70672 80766 # Sequences Clustered FIGURE 7 Finally, figure 8 shows the speed-up for eight different data sets. The speedup ranges from 15 to 32 and is correlated to the novelty of the data set being clustered. Data sets that are more novel see better speedup because the number of unsuccessful comparisons filtered out is much larger than for data sets that are more redundant. This makes the denominator smaller relative and thus increases speedup. For less novel data sets, the number of comparisons is much closer because the potential for filtering is less (fewer cluster representatives). For these data sets, the clustering output by each version is close enough to be considered the same. Speedup Old Execution Time New Execution Time Speedup for ~10Kseq Chunks of UI RatEST Data 35 32.56 31.64 29.48 30 Speedup 26.34 25 23.19 23.08 20.11 20 15.36 15 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (1654, 1656) (2399, 2397) (2040, 2040) (2378, 2372) (4703, 4703) (5873, 5871) (6783, 6782) (7616, 7627) Chunk (Number in Parenthesis is Old vs. New # of Clusters) FIGURE 8 Other New Features The ability to try the reverse compliment of a sequence when doing sequence comparisons was added. DNA is made up of two complementary strands and sometimes it isn’t known which strand a sequence comes from. In addition, sequencing errors can cause miss-annotation of which strand a sequence was read. In order for two overlapping sequences from different strands to match, one of them needs to be reverse complimented. This simply means that the sequence order is reversed and each base is complimented: A <=> T, C <=> G. This feature results in a tighter clustering (fewer clusters) when sequences from both strands are present in a data set. A graphical JAVA viewer was developed to aid in the visualization of clusters. The output of uicluster is a plain ASCII text file containing thousands of annotated sequences. It is difficult to look at such a file in a text editor and discern what is going on. The cluster viewer makes it easier to find a given sequence and the cluster it belongs too. It also performs color highlighting of the matching regions of sequences in a cluster. Figure 9 shows the main GUI interface. The cluster representatives are listed in the upper left list. When one of the representatives is clicked, the list of the sequences it represents (the other members of the cluster) appears in the upper right pane. The sequence data for the two selected sequences is displayed in the lower two panes; cluster representative on top, current cluster member on bottom. The matching region of at least 38/40 bases is highlighted in blue. To enable the viewing of large uicluster output files, random access file I/O was used so that the entire file doesn't need to be loaded in memory. When the file is opened, a single pass is taken through the file to record the byte offset of each cluster representative. When a sequence name is clicked with the mouse, the sequence data is dynamically read from the file using the stored offset information. FIGURE 9 Future Work There are many features proposed for upcoming releases of uicluster: 1) Cluster Assembly With the current version, the cluster representative is chosen to be the longest sequence in the cluster. This representative doesn't necessarily represent every sequence in the cluster, however. Assembling the sequences of a cluster into a consensus sequence that contains information from all non-redundant sequence regions could create a better representative. 2) Cluster Merging Currently, if an input sequence is similar to multiple cluster representatives it is added to the first one that matches. It would be better if the program would keep going and remember all of the cluster representatives that the input sequence matches. Then the program could try to merge clusters based on this information. Since this feature would increase the execution time of clustering significantly, it will be implemented as an optional feature that the user can choose to enable at run-time. 3) Alternative Splice Detection Genomic DNA is processed by a cell before it is translated into protein. During this processing, regions of bases called exons can be rearranged or left out entirely. This is thought to serve a regulatory function by making the production of certain proteins a probabilistic operation. If sequences from processed cDNA are being clustered, there is a potential to detect the effects of the processing. This is valuable information because it shows with certainty different permutations of a gene before it is translated into a protein. Currently, this information has to be predicted using genomic DNA and complicated software systems. 4) Use Draft Sequence A draft version of the entire human genome will be available very soon. This genomic sequence data could be used to verify that the alternative splices detected by the clustering program are accurate. It could also be used to speed up the sequence assembly process when creating the consensus cluster representatives. 5) Manual Cluster Finishing There are bound to be errors in the clustering which only a human can detect and correct efficiently. This feature would allow an expert human to examine the results of a clustering and make changes as necessary. Such editing capabilities could be added to the current JAVA cluster viewer. 6) Quality Information Every base read by a sequencing machine also gets a quality value. The clustering program could take this information into account when comparing sequences and when assembling sequences. Low quality sequence should not be used as the basis for such operations. However, it can be useful for extending matches and eliminating inconsistencies in sequence assemblies. Many discussions have already taken place about how to best implement these features. Development is currently underway by the author and it will likely be the topic of a future master's thesis. Conclusion Optimizations were added to an EST clustering tool that significantly increased the rate at which processing can be performed. This is important because large amounts of data need to be clustered on a weekly basis in the University of Iowa sequencing labs. The time necessary to do this processing has become unmanageable as the data sets have grown in size. In version 2.0, a clustering of rat EST data that previously required 14 hours has been reduced to 30 minutes. This speed will be sufficient for the foreseeable future. In addition to the optimization, the ability to form clusters that take into account the directionality of a sequence was added. This results in a tighter clustering when sequences of mixed orientation are processed. Finally, a JAVA based cluster viewer was created to make it easier to interpret the clustering program’s output.