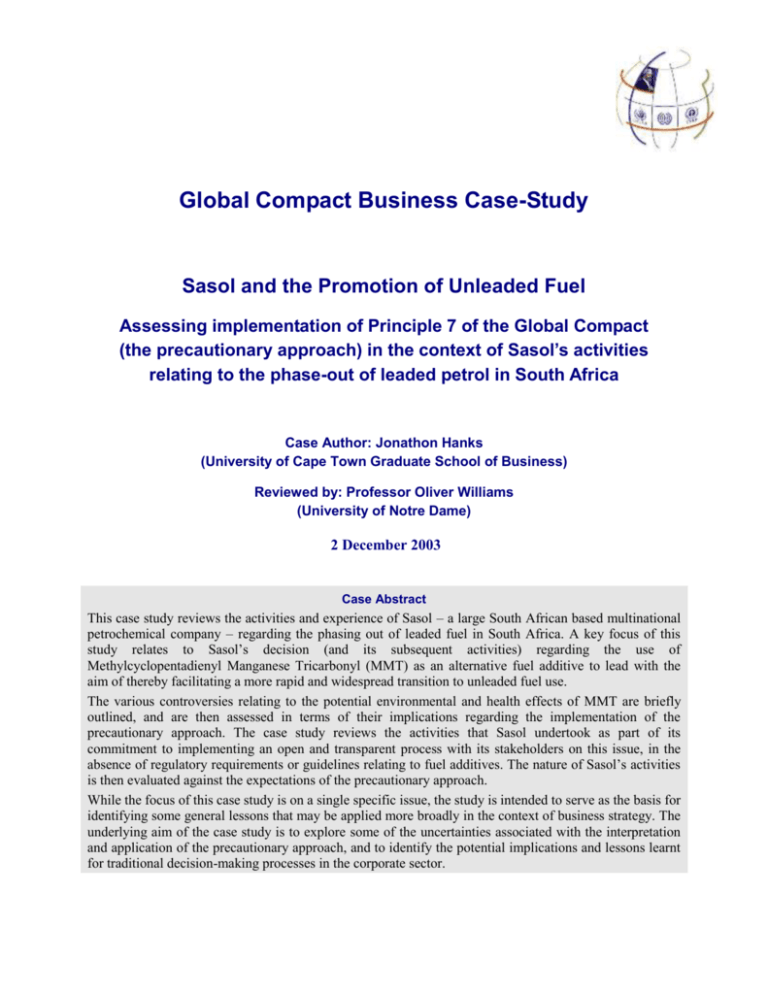

3 The Case Story: Implementing the precautionary approach?

advertisement