Nature Vs. Nurture

advertisement

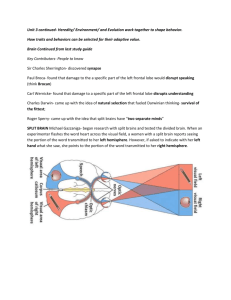

Nature, Nurture, and Human Diversity CHAPTER OBJECTIVES 1. Describe the composition and physical location of genes. 2. Discuss the impact of evolutionary history on genetically predisposed behavior tendencies. 3. Identify gender differences in sexual behavior, and describe and evaluate evolutionary explanations for those differences. 4. Describe how twin and adoption studies help us differentiate hereditary and environmental influences on human traits. 5. Discuss how differences in infant temperament illustrate the effect of heredity on development. 6. Describe how behavior geneticists estimate trait heritability, and discuss the interaction of genetics and environmental influences. 7. Discuss the potential promise and perils of molecular genetics. 8. Explain how twins may experience different prenatal environments, and describe the effect of experience on brain development. 9. Describe how development is influenced by the individual’s culture. 10. Explain how biological sex is determined, and describe the role of sex hormones in biological development and gender differences. 11. Discuss the importance of gender-roles, and explain how social and cognitive factors contribute to gender identity and gender-typing. 12. Discuss the danger of blaming nature and nurture for our own personal failings. GENES: OUR BIOLOGICAL BLUEPRINT When egg and sperm unite, the 23 chromosomes from the egg pair with the 23 chromosomes from the sperm. Each chromosome is composed of a coiled chain of a molecule called DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA is in turn composed of thousands of genes, the biochemical units of heredity. They provide the blueprint for protein molecules, the building blocks of our physical and behavioral development. Our genes are composed of biochemical letters called nucleotides. REMEMBER: The Human Genome project, the discovery of the common sequence of all three billion letters within our DNA and thus the complete instructions for making a human. Evolutionary psychologists study how natural selection extended over many years and, feeding off new gene combinations and mutations, has shaped our universal behavioral tendencies. At the dawn of human history, some individuals engaged in behaviors that enabled them to survive, reproduce, and thus send their genes into the future. The genes of those who made less fortunate choices were lost from the human gene pool. Nature predisposes us, as mobile gene machines, to make choices that worked for our ancestors. For example *: Gender differences in sexual behavior --- One of the largest reported gender differences is women’s greater disapproval of and lesser willingness to engage in casual, uncommitted sex. With few exceptions anywhere in the world, men are more likely than women to initiate sex. Men also have a lower threshold for perceiving warm responses as a sexual come-on. The unfortunate response can range from sexual harassment to date rape. Evolutionary psychologists explain these differences by noting that compared with eggs, sperm are cheap. While a woman cares for a single infant, a man can spread his genes by impregnating other females. Women most often send their genes into the future by pairing wisely, men by pairing widely. CRITICS argue that evolutionary psychologists make too many hindsight explanations (remember Chapter 1?). In addition, much of who we are is not hardwired, but learned. Cultural expectations also shape the genders. BEHAVIOR GENETICS: EXPLAINING INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES Comparisons of identical twins, who are genetic clones, and fraternal twins, who develop from different eggs, help researchers tease apart the effects of heredity and environment. Research findings show that identical twins are much more similar than fraternals in abilities, personality traits, and even interests. Genes matter (?). The discovery that identical twins separated at birth show remarkable similarities also suggests genetic influence. Adoption enables comparisons with both genetic and environmental relatives. Some of the adoptees’ traits bear more similarities to their biological parents than to their caregiving adoptive parents. Nonetheless, the latter do influence their children’s attitudes and values. Clearly nature and nurture shape one’s developing personality. Criticism of the Minnesota Twin Study * The infant’s temperament includes inborn emotional excitability. From the first weeks of life, some babies are more relaxed and cheerful, others are more tense and irritable. These differences in temperament tend to endure * (Remember however that environment can change or reinforce these tendencies). Genetic influences may also help explain why infants of Asian descent tend to be calmer and more placid than are infants of European descent. Activity, sociability, emotionality (distress, fearfulness, anger) are all parts of temperament. Using twin and adoption methods, behavior geneticists mathematically can estimate the heritability of any trait --- the extend to which variation among individuals is due to their differing genes. We are all the products of interactions between our genetic predispositions and our surrounding environments. Our genes affect how our environment reacts to and influences us. CAUTION: These figures apply to the population as a whole, not to individuals. Promise and perils of molecular genetics: In dozens of labs worldwide, molecular geneticists are teaming with psychologists in search of genes that put people at risk for genetically influenced disorders. Potentially, steps may be taken to prevent problems before they happen. With this benefit, however, also come risks of labeling people in ways that may lead to discrimination or self-fulfilling prophecies. Prenatal screening also poses hopeful possibilities and difficult problems as parents become able to select the traits. Obviously, parents will select for health --- and perhaps for brains, beauty, and athleticism. However, by selecting out certain traits, we may deprive ourselves of future Handels, van Goghs, Lincolns, and Dickinsons, all troubled people. ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCE Although Myers reports that two children from the same family are as different from one another as pairs of children selected randomly from the population suggesting that parents should feel less pride in their children’s successes as well as less guilt over their failures, he neglects to emphasize the findings of current research on how parent-child interactions previously unrecognized as significant may greatly affect children’s growth and development. For example, the kind of fantasy play that parents engage In with children help children learn to regulate and control emotions. The form of the questions parents ask and the style of their comments also influence children’s language development and later cognitive functioning. So, children learn from all kinds of interactions with parents *. Many factors shape parents’ behavior. Children’s temperament and individual qualities shape what parents do, but many other influences also come into play, e.g., the role of society, ecological context, culture, ethnicity, family circumstances, etc. CAUTION: Please do NOT undermine the influences of parenting on children’s development, as your author does. Myers assumes that parents parent all of their children in the same manner which simply cannot be. The affection, attention, and discipline provided by parents are significantly different for siblings *. Differences in prenatal environments: Some identical twins have separate placentas. One placenta may have a more advantageous placement that provides better nourishment and thus a better placental barrier against viruses. Even when twins share the same placenta, one may get a richer blood supply and weight more at birth. Research indicates that young rats living in enriched environments develop a thicker and heavier brain cortex. Stimulated infant rats and premature babies gain weight more rapidly and develop faster neurologically. Experience preserves activated neural connections while allowing unused connections to degenerate. Peer Groups: Experiences with peers socialize children. Immigrant children placed in peer groups of non-immigrants quickly lose their parents’ culture. Teens who start smoking typically have friends who model smoking. Peers are important in learning cooperation, for finding the road to popularity, and for inventing styles of interaction among people of the same age. Culture: is the enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, and traditions shared by a large group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next. All cultural groups evolve their own norms, rules that govern their members’ behaviors. Cultures vary in their requirements for personal space, their expressiveness, and their pace of life. Cultures do change over time. Memes are self-replicating ideas, fashions, and innovations that, like genes, compete to get copied into our memories and media. Cultural values also impact child-rearing practices. For example, Westernized cultures raise their children to be independent. Many Asians and Africans who live in communal cultures focus on cultivating emotional closeness. GENDER Biological sex is determined by the 23rd pair of chromosomes, the sex chromosomes. The member of the pair inherited from the mother is an X chromosome. The X (female) or Y (male) chromosome that comes from the father determines the child’s sex. The Y chromosome triggers the production of the principal male sex hormone, testosterone, which in turn triggers the development of external male sex organs. A female embryo exposed to excess testosterone is born with masculineappearing genitals. Until puberty such females tend to act in more aggressive, “tomboyish” ways than is typical of most girls. The fact that people may treat such girls more like boys illustrates how early exposure to sex hormones affects us both directly (physically) and indirectly, by influencing experiences that shape us. Gender roles, gender identity and gender typing: A role refers to a cluster of prescribed actions --- the behaviors we expect of those who occupy a particular social positions. The fact that gender roles --- our expectations about the way men and women behave --- vary across cultures and time illustrates the social construction of gender. For example, in nomadic societies of food gathering people, there is little division of labor by sex. Thus, boys and girls receive much the same upbringing. In agricultural societies, women stay close to home while men often roam more freely. Such societies typically socialize children into more distinct gender roles. Even among industrialized countries, gender roles vary. In north America, medicine and dentistry are predominantly male occupations; in Russia, most medical doctors are women, as are most dentists in Denmark. Society assigns even those few whose biological sex is ambiguous at birth to a gender, the social category of male and female. The result is our gender identity, our sense of being male and female. To varying degrees, we also become gender-typed, acquiring a traditional male or female role. Social learning theory assumes that children learn gender-linked behaviors by observing and imitating significant others and by being rewarded and punished. Gender schema theory assumes that children learn from their cultures a concept of what it means to be male or female and adjust their behavior accordingly. This theory combines social learning theory with cognitions. BIG CAUTION: Although we are the products of nature and nurture, we are also an open system. Sometimes, people defy their genetic bent as well as environmental pressures. We are not only creatures but also creators of our worlds. The stream of causation that shapes the future runs through our present choices. Blaming nature and nurture evades PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY!!!