Eurocentrism

advertisement

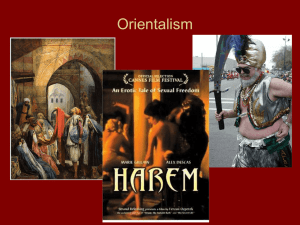

Eurocentrism The writer Neal Ascherson suggested that “on the shores of the Black Sea were born a pair of Siamese twins called ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism’” (Ascherson 1995, TK[AU 1: Please supply the page on which that quotation is found. Also, please check what edition of the book you have. If it’s a different year/publisher, etc., from what we’ve indicated in the Further Reading section, please supply the details, and we will change the listing in the Further Reading section.] The observation about these twins is surely incisive and universal, even if the Black Sea venue may be questioned. The civilized and barbarian twins have had many births and rebirths in all times and places occupied by people. Moreover, they have ever been co-terminus with centrisms<M>Greco-, Islamic-, Sino-, Euro-, U.S.-, Western- and many others<M>each of which labeled all others barbarians. What distinguishes Eurocentrism (actually Western-centrism, since Eurocentrism incorporates such geographically disparate regions as North America and Australia as well as Europe) is that during the past century or more it has been accompanied by power, which it has used to legitimate, extend, and maintain itself and its rule in the world. In 1978 the literary critic Edward Said condemned ''Orientalism''<M>Western conceptions of the Islamic world<M>as a grab-bag of ill-defined characteristics that are distinctive only in allegedly being non-Western. Indeed, the very invention of Orientalism was not so much an attempt to say something about ''the Orient'' as an attempt to delineate and distinguish ''the West" from "the rest," as the scholar Samuel Huntington put it in his 1993 article “Clash of Civilizations” in the journal Foreign Relations. The media immediately welcomed this formulation of an alleged clash between The West and (in particular) China and Islam; and they have even more widely accepted it as an explanation of world events since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. However, Gernot Köhler, a scholar of international relations and the world economy, has suggested that the sort of thinking that leads to Orientalism or to theories of civilization clashes goes hand in hand with the notion of global apartheid: The first is an ideological facet of the second, just as the notion of the “white man's burden" was an ideological facet of European colonialism and imperialism. Nor does it appear that decolonization of the second half of the twentieth century has put those notions to rest in the sands of history. On the contrary, the rhetoric of leaders such as Britain’s Prime Minister Tony Blair and the United States’ President George W. Bush is replete with claims that they are defending civilization (with the unspoken assumption being that they mean Western civilization) against outside threats<M>this in spite of the fact that many argue that some of their methods, such as Bush’s doctrine of preemptive war, threaten to destroy one of civilization’s most precious gifts: international law and institutions to prevent man from killing man in a general war of all against all. The Historical Development of Eurocentrism Eurocentrism currently exerts widespread influence in the humanities, social sciences, and even the natural and physical sciences, but it was not always so. The 1911 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Current English defined orient as “The East; lustrous, sparkling, precious; radiant, rising, nascent; place or exactly determine position, settle or find bearings; bring into clearly understood relations; direct towards; determine how one stands in relation to one's surroundings. Turn eastward.” By 1980, however, the American Oxford Dictionary defined it simply as “The East; countries east of the Mediterranean, especially East Asia.'' The Orient as a model to be acclaimed and copied had become the antimodel to be defamed and shunned. Such European luminaries as the philosopher René Descartes (1596<N>1650), the writer Voltaire (1694<N>1778), and the economist Adam Smith (1723<N>1790), however, were still persuaded by the former definition. Although the French intellectual Montesquieu (1689<N>1755) was an early forerunner of the change to a more negative image of the East, the major transformation in opinion came with the European industrial revolution and colonialism, especially from the mid-nineteenth century, with those proponents of dialectical change, G. W. F. Hegel (1770<N>1831) and Karl Marx (1818<N>1883). Their total Eurocentrism really did turn views of the world on its head. They began a tradition in the humanities and social sciences of differentiating the progressive “us” from the traditional “them” that continues to this day. Historiography<M>even ''world'' history<M>in the West has been entirely Eurocentric, running only on a westward track from ''the Orient" to Western Europe and America. Works in this vein include the uncompleted Weltgeschichte (Universal History) of Leopold von Ranke (1795<N>1886), the twelve-volume Study of History (1934<N>1961) of Arnold Toynbee (1889<N>1975), who described the rise and fall of twenty-one ''civilizations" and the “arrested development” of five others, and William McNeill's Rise of the West, originally published in 1963. Nor is the history of science immune from a focus on the West: The very notion of a seventeenth-century scientific revolution in Europe that is taken to be the basis of Europe’s technological and industrial revolution tends to downplay scientific innovation or contributions from other parts of the world.[AU 2: Okay?] Eurocentrism in Sociology and Anthropology From the 1850s this dichotomy of the West and the rest and attendant praise of things Western has been the hallmark of all Western social theory. The nineteenth-century French "father of sociology" Auguste Compte (1798<N>1857) and the British legal scholar Henry Maine (1822<N>1888) distinguished between European "science" and "contracts," which allegedly replaced age-old "tradition." The French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858<N>1917) distinguished "organic" and "mechanical" forms of social organization, and the German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnis (1855<N>1936) alleged a transition from traditional gemeinschaft (“community”) to modern gesellschaft (“society”). In the twentieth century the sociologist and economist Max Weber (1864<N>1920) considered European rationality to be the essential ingredient in Western success, as described in The Protestant Ethic and the spirit of Capitalism (1904<N>1905). During the Cold War, the sociologist Talcott Parsons, who popularized Weber in the United States, distinguished Western "universalist" social forms from the "particularist" social forms of other cultures, and the anthropologist Robert Redfield found a contrast and transition between traditional "folk" and modern "urban" society and a certain symbiosis between "low" and "high” civilizations.[AU 3: Can we add a sentence here saying explicitly that the “good” item in each dichotomy is always (or usually) equated with what exists in the West?] The modernization theory that dominated postwar social sciences and economics distinguished Western modernization from other cultures’ and regions’ traditionalism. The economist W. W. Rostow's Stages of Economic Growth (1959) was a major vehicle for articulating modernization theory and followed the same Eurocentric theoretical path from traditional to postindustrialist society. As late as 1998, David Landes's best-selling The Wealth and Poverty of Nations assured readers of the exceptionality of European culture. Eurocentrism in the Twenty-First Century In its present incarnation, Eurocentrism entails the successful, free-trading West teaching the rest of the world the merits of a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps ethic, which will, proponents believe, bring the wealth of the West to the poor rest.[AU 4: Your original conclusion is a little too of-the-moment for use in the encyclopedia. Could you give us a sentence or two about the concept of multiculturalism (is it just another way of condescending to the rest?) or about how the rest of the world is currently reacting to this form of Eurocentrism?] Andre Gunder Frank Further Reading [AU: The titles here are drawn from your article, but can you recommend a work other than Orientalism that attacks the notion of Eurocentrism?] Ascherson, N. (1995). Black Sea. London: Cape. Huntington, S. (1993). Clash of civilizations. Foreign Affairs, 72(3), pp 22<N>28. Jones, E. (1981). The European miracle: Environments, economies and geopolitics in the history of Europe and Asia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Landes, D. (1998). The wealth and poverty of nations: Why are some so rich and others so poor. New York: W. W. Norton. McNeil, W. (1963). Rise of the West: A history of the human community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rostow, W. W. (1961). Stages of economic growth: A non-Communist manifesto. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. Toynbee, A. (1934<N>1961). A study of history. London: Oxford University Press.