waivers_mcrory

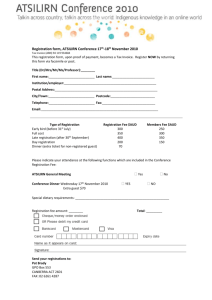

advertisement

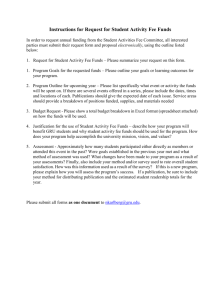

DO FEE WAIVERS, EXEMPTIONS

AND OTHER CLASSIFICATIONS

SATISFY EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAW?

Michael W. L. McCrory

{A0009041.DOC/}1

DO FEE WAIVERS, EXEMPTIONS AND OTHER CLASSIFICATIONS

SATISFY EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAW?

Impact fees are generally viewed by the courts as an exercise of the local

jurisdiction’s police power. When challenged on equal protection grounds, fee statutes

are subject to the traditionally broad deference that allows jurisdictions wide latitude for

legislative acts that are reviewed only to determine if there is some plausible, rational

governmental purpose supporting the statute. City of Cleburne, Tex. v. Cleburne Living

Center. 1 Development impact fees are presumed to be a valid exercise of the

legislative authority to regulate land use.2

That judicial deference, however, decreases as challenges focus on more

precise classifications within impact fee regulations that may have discriminatory effects

and such deference may evaporate with classifications for waivers or exemptions that

are unrelated to the fundamental purpose of the impact fee. Different classifications

within an impact fee establish subclasses within the overall class. These are more likely

to be viewed in equal protection terms of whether the subclasses are treated equally

with respect to other subclasses rather than whether the classification serves a

legitimate governmental purpose.

Waivers, exemptions and other classifications which are applied to individual

cases create such subclasses and raise two additional equal protection challenges.

Such actions may lead to claims that individuals have been treated in an arbitrary and

irrational manner and therefore have an equal protection claim under Village of

Willowbrook v. Olech.3 Such actions may also become the type of individualized

determination that is subject to the stricter scrutiny of the Nollan and Dolan cases.4

At the broadest level of review, differences in how impact fees are applied are

reviewed to determine whether there is a rational basis for the classification. Thus the

application of fees to some, but not all, areas within a jurisdiction has been upheld 5 as

have imprecise formulas for determining fees.6 In Home Builders Association of Central

Arizona v. City of Scottsdale, the court examined the nature of the governmental

purpose for the fees but deferred to the local jurisdiction on how to meet that purpose

and did not second guess the feasibility of the local jurisdictions plans.

1

473 U.S. 432 (1985).

Home Builders Association of Central Arizona v. City of Scottsdale, 187 Ariz. 479, 930 P.2d 993 (1997);

San Remo Hotel L.P. v. City and County of San Francisco, 41 P.3d 87 (Cal. 2002); Home Builders

Association v. Des Moines, 644 N.W.2d 339 (Iowa, 2002); Home Builders and Contractors Association v.

Palm Beach County, 446 So.2d 140 (Fla. App., 1984).

3 526 U.S. 562 (2000)

4 Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 483 U.S. 825 (1987); Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374

(1994).

5 Palm Beach County, supra.

6 Black v. Kileen, 78 S.W.3d 686 (Tex. App. 2002); Southport Development Group, Inc. v. Township of

Wall, 709 A.2d 226 (N.J. App. 1998); Agencia La Esperanza Corporation v. Orange County, 2002 WL

681798 (Ca. App. 2002) [Unpublished]

2

{A0009041.DOC/}2

In Black, the court upheld water and sewer connection fees that were in excess

of the actual connection costs. The court held that the City could include indirect costs

in its fee resulting in a fee that is higher than actual costs. Since the plaintiff had failed

to account for these indirect costs, and since the plaintiff bore the burden of proof, the

court could not determine that the fee was unreasonable.

The treatment of different uses also raises potential equal protection concerns.

In Home Builders Association v. City of West Des Moines, supra., upheld separate

classification of single family residence and multi-family residences and upheld the

exclusion commercial uses from the City’s park fee.7 In Bogue Shores Homeowners

Association, Inc. v. Town of Atlantic Beach, 8 the court found that assessing water rates

for single family residences based upon the size of the water line and for multi-family

complexes based on the number of units was necessary to avoid discriminating against

single family residences. While the size of the line was an accurate measurement for

one family, the multi-family complexes would require far more usage which was not

accounted for in the size of the line.9

Even the deferential standard for equal protection analysis has its limits. As

noted in Tyson Smith’s presentation, fees that cannot provide any benefit will violate

equal protection. Thus in St. John’s County,10 the application of the fee to cities that

would never receive any benefit was discriminatory and in Volusia,11 an adult mobile

home park that could not have children living on the premises could not be subjected to

a school impact fee without violating equal protection.

The cases applying the deferential standard focus on the broad and relatively

equal general application of impact fees. Waivers and exemptions provide exceptions

to those general, uniform applications and as such raise additional equal protection

issues. Often, waivers and exemptions are intended to achieve a governmental

objective that is distinct from the purpose of the fee such as excluding low

income/affordable housing from the cost of a road impact fee or excluding schools from

having to pay traffic or park impact fees.

The central problem with such waivers and exemptions is where the basis for this

sub-classification is not related to the purpose of the impact fee. Are such subclassifications judged on their governmental purpose or the purpose of the fee? The

answer to that may well determine the validity of the waiver or exemption.

7West

Des Moines applies a tax analysis rather than a regulatory fee analysis. Since tax statutes do not

have to provide the same benefit to the person paying the tax as a regulatory fee, such statutes may be

given more deference for equal protection purposes.

8 428 S.E.2d 258 (N.C. App. 1993).

9 See also: Ellis v. Clovis Unified School District, 2002 WL 1011515 (Cal App. 2002), an unpublished

case holding that a school impact fee did not have to distinguish between the impact of single family

residences and multi-family projects.

10 St Johns County v. Northeast Florida Builders Ass’n, Inc., 583 So.2d 635 (Fla. 1991).

11 Volusia Co. v. Aberdeen at Ormand Beach, 760 So.2d 126 (Fla. 2000).

{A0009041.DOC/}3

It is well accepted that providing low income housing is a legitimate governmental

function and impact fees may be designed to accomplish that goal.12 Thus, if a waiver

to a road or park fee for affordable housing units is viewed in terms of whether it furthers

a legitimate governmental purpose, there should be no doubt about it’s validity.

As an exception to an otherwise valid fee, however, the issue may become one

of whether it is related to the purpose of the fee. Affordable housing, whether privately

or publicly constructed, will essentially have the same effect on traffic and park use as

any other house of comparable size. Analyzed from this perspective, the fee is

“arbitrary and irrational”.

The importance of the question of what to analyze is best exemplified by the

Brook Park case from Tyson Smith’s presentation.13 Brook Park I involves the

assessment of a parking tax at rate to the local exhibition center and at a lower rate to

the local airport. The trial court found “a legitimate difference in the number of vehicles

and people attending the exhibition center and the associated cost of necessary

municipal services . . . .”14 The Court of Appeals rejected this analysis holding that none

of these factors effected the parking use. Since parking was the reason for the excise

tax, none of the factors cited by the trial court justified the different rates. The different

rates therefore were not supported by any rational basis and were invalid.

The Ohio Supreme Court rejected that analysis.15 In Brook Park II, that court

returned to the deferential standard of review and an analysis of whether the different

classifications further legitimate state objectives. This allowed the court to examine the

objective of maintaining the economic viability of the airport through a preferential rate,

the guaranteed payout from the airport and the desire to aid development of the part of

the city that housed the airport. Since these are legitimate governmental interests, the

different tax rates were upheld.16 This case was, however, reviewed as a tax case

rather than a regulatory fee case and it is not at all clear that such reasons would be

accepted for different regulatory fees.

Waivers and exemptions that are provided to individual applicants raise

additional issues concerning how each individual is treated in the process. In Olech, the

United States Supreme Court made it clear that equal protection claims were not solely

the province of suspect classes and fundamental rights. Olech establishes that an

equal protection claim may lie where the plaintiff can establish that it “has been

intentionally treated differently from others similarly situated and that there is no rational

basis for the difference in treatment.”17 Under this precedent, “an individual who does

not claim membership in any group narrower than the human race can still obtain a

12

San Remo Hotel, supra.

Park Corp. v. Brook Park, 2002 WL 973082 (Brook Park I).

14 Brook Park I, paragraph 31.

15 Park Corporationv. City of Brook Park, 807 N.E.2d 913 (Ohio, 2004) (Brook Park II).

16 Cf: Massachusetts Municipal Wholesale Electric Company v. City of Springfield, 726 N.E.2d 973 (Mass.

App. 2000) (differential utility rates to promote industrial users within city was discriminatory).

17 Olech, supra., 528 U.S. at 564.

13

{A0009041.DOC/}4

remedy under the equal protection clause for ‘irrational and wholly arbitrary’

treatment.”18

The application of Olech to land use decision making and regulations is

described in the attached presentation of Michael S. Giaimo to the Georgetown

University Law Center Regulatory Takings Claims Seminar, October, 2003. As set forth

in that paper, there are no clear guidelines on the extent to which the “class of one”

claims require evidence of ill will, spite, and intentional acts of discrimination. As Mr.

Giaimo notes from the Seventh Circuit cases, there are potentially two subsets of the

“class of one” cases, one based on intentional treatment that is different from others

similarly situated and without any rational basis and one based on different treatment of

persons in identical circumstances based upon illegitimate animus. These two subsets

may represent distinct claims or the latter may be a variation of the former. 19

The central nature of the subjective intent behind government actions in an Olech

claim makes it significantly more difficult for government entities to dispose of such

claims on the pleadings or in summary judgments. Allegations of ill will from

government employees and determinations of what constitutes a “similarly situated”

party will be fact intensive and unique to each case. In Squaw Valley Development

Company v. Goldberg,20 a claim was allowed to proceed against an agency supervisor

who more strictly enforced rules in an effort to obtain compliance from a long term

violator of agency rules where there was an issue of material fact as to whether the

official acted from personal animosity. By contrast, in Bell v. Duperrault,21 allegations of

rude treatment were not sufficient to show a “deep seated animosity” that would sustain

an Olech claim.

Waivers and exemptions to impact fees which will inherently involve the review of

a individual facts may be particularly susceptible to such claims of “irrational and wholly

arbitrary” application. Some may involve claims that another applicant had more

favorable treatment or that a formula or data source was allowed in one instance but not

another. Others may argue that they are not producing any impact and therefore must

be exempted. Given that under Olech any individual may claim a denial of equal

protection for what is perceived to be “irrational and wholly arbitrary”, these individual

decisions will involve greater scrutiny.

In addition to the equal treatment issues raised by potential Olech claims,

waivers and exemptions for individual cases may trigger greater scrutiny under the

Nollan and Dolan cases. Nollan clearly requires that the government exaction be

directly related to the purpose of the regulation as opposed to promoting an unrelated

governmental purpose. Dolan requires that the exaction be “roughly proportional” to the

actual impact of the development.

18

Indiana Land Company v. City of Greenwood, 378 F.3d 705, (2004)

The more recent decision in Indiana Land Company, supra., confirms the “tension” between these

interpretations with a dissent asserting that no such tension exists.

20 375 F.3d 936 (9th Cir. 2004).

21 367 F.3d 703 (7th Cir. 2004).

19

{A0009041.DOC/}5

There are conflicting decisions on whether the stricter scrutiny of Nollan and

Dolan apply to impact fee regulations at the general level since the fees are legislatively

determined and uniformly applied.22 Where there is determination on an individual

application for a waiver or exemption, however, there is no longer the same premise of

uniformity or standardization. These individual applications appear to fall squarely

within the type of individualized determination that was the core of the Dolan case.

Thus it is more likely that analysis will require that the fee imposed be related in nature

and extent to the impact of the development and the affirmative showing of how the fee

advances a legitimate governmental interest.23

In summary, where impact fees provide for uniform classifications and application

and are based upon reasonable evidentiary grounds, the courts will generally defer to

the policy judgments of the legislative bodies. Where the fee regulations depart from

nature and purpose of the fee itself and introduce unrelated public policies and where

fee regulations provide for individual waivers, exemptions and determinations, local

governments will face significantly greater scrutiny for compliance with equal protection

principles. The challenge for individual cases will be to determine which analysis

applies.

22

Rogers Machinery Inc. v. Washington County, 45 P.3d 966 (Or. App), rev. den. 52 P.3d 1057 (Or.

2002); Garneau v. City of Seattle, 147 F. 3d 802 (9th Cir. 1998); Home Builders Association of Central

Arizona v. City of Scottsdale, supra., McCarthy v. City of Leawood, 894 P.2d 836 (Kan. 1995); cf: Ehrlick

v. City of Culver City, 911 P.2d 429 (Cal.) cert. den. 519 U.S. 929 (1996); Home Builders Ass'n of Greater

Des Moines v. City of West Des Moines, 644 N.W.2d 339 (Iowa May 08, 2002) (NO. 00-0351, 99-2025),

as amended (May 31, 2002)

23

Town of Flower Moundv. Stafford Estates Limited Partnership, 2004 WL 1048331 (Tex) (Not released

for publication), 71 S.W.3d 18 (Tex. App. 2002); Agencia La Esperanza Corporation, supra.

{A0009041.DOC/}6