REVIEW OF DEATH AND CREMATION CERTIFICATION POLICY

advertisement

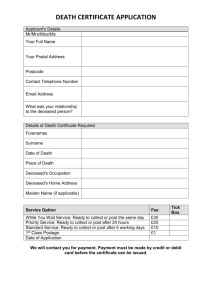

PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) REVIEW OF DEATH AND CREMATION CERTIFICATION POLICY Introduction 1. In the Review of Coroners and Death Certification in England, Wales and Northern Ireland the response by the BMA agreed with the review’s conclusion that “neither the certification nor the investigation system is ‘fit for purpose’ in the circumstances of modern society” and support the aims of the service identified. However, no system can ever provide complete protection against those intent on covering up criminal activity, and the aim of doing so needs to be balanced against the financial implications and other effects of introducing a new system. 2. Further, that the proposed medical audit service has merits; in particular, there is a need to bring together currently fragmented functions into a single organisational structure with clear accountabilities, to provide training and support in the certification process, and to encourage the assessment and audit of certification processes. 3. It would appear a sensible premise that the current arrangements whereby there is an obligation through the Births, Deaths and Cremation Certification (Scotland) Act 1965 for a doctor to issue a death certificate when in a position to do so, should be maintained and reinforced. 4. In England and Wales there is a statutory duty laid upon the doctor who attended the deceased during the terminal illness to issue a medical certificate of the cause of death 1. In Scotland the revised guidance attached to the books of Death Certificates indicates that under the Registration of Births, Deaths and Marriages (Scotland) Act 1965, “if you are a registered medical practitioner and attended during the last illness of the deceased, you have to fill in a medical certificate of cause of death”. There is currently no legal requirement for the certifying doctor to view the deceased after death but it would seem sensible to do so for the reasons set out above. Certification of the fact of death based on an agreed protocol could enable other appropriate persons to confirm death with confidence. 5. As a primary safeguard, the actual certification of cause of death (in distinction to the pronouncement of the end of life) should be undertaken by a registered medical practitioner. One of the current difficulties being encountered is that the deceased’s own general medical practitioner may not be on duty if the death occurs out of hours and reinforcement of the statutory requirement to certify death to ensure personal knowledge of the deceased in the process would also appear reasonable. At the present time, there is no legal obligation upon a doctor to complete a cremation certificate but for obvious practical reasons, the doctor in attendance in that person’s final illness undertakes this function. Should there be amalgamation of the death and cremation certification process, our recommendation is that this should become a statutory obligation albeit there is likely to be inconvenience to that doctor as the deceased may well have been moved to a funeral parlour/mortuary outwith the immediate locality of where death occurred. 1 Registration of Births and Deaths Regulations 1987, SI 1987/2088. Page 1 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) Fact of death Certifier 6. There is much pressure to derogate the responsibility from doctors to nurses, to ambulance technicians and others. Paradoxically, this is a realistic aspiration in hospitals where medical personnel are readily available, but less so in the domestic, public or commercial contexts. In the first, a patient’s GP will usually attend; if the death is expected or the history is ‘good’ the doctor may proceed to give a death certificate. 7. Although it may be in order for life to be pronounced extinct by these other groups, one has to bear in mind that a small number of instances occur each year where the Medical Defence Organisations are aware of death erroneously being diagnosed and the patient subsequently found alive. Typically, this will involve hypothermia, perhaps hypothyroidism or a drugs overdose (not necessarily illicit drugs). 8. Through the BMA’s Forensic Medicine Committee and the Association of Forensic Physician’s Education and Research Committee, it should be possible to establish an acceptable protocol for use in pronouncing life extinct. 9. Action: ascertain the proportion of certificates granted in various categories. 10. If the doctor is unable to certify (or if ‘999’ has been dialled) the police become involved: depending on the local practice, police surgeon assistance is used, primarily to enquire if the death ought to be treated as suspicious in order to try and exclude any criminality. In public access circumstances, a body is assessed by ambulance personnel, and may or may not be removed. 11. Problems: competence in deciding person is dead; authority to remove; ability to distinguish untoward circumstances; to strip a body in a house; putrefaction; adequate light; recording of circumstances; access to history of events immediately preceding death and past medical history. Page 2 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) Locus 12. Difficulties have already been alluded to (light, access, assistance to examiner). If the work is to be assumed by personnel other than doctors, what are the skills required? Is there any advantage to the use of digital photography if the medical examiner is not going to attend the locus in all cases? 13. Action: ascertain the proportion of cases dealt with by ambulance personnel at present and the skills they have to ‘read’ a locus. 14. We can be confident that doctors without training in clinical forensic medicine lack the necessary skills. It is of fundamental importance that we reintroduce legal and forensic medical education as a core skill at medical schools even if this necessitates a return to a degree of didactic teaching. 15. Problems: the locus gives many clues, but training and reinforcing that training need a major commitment of resources; GPs are unlikely to see this as a priority. Page 3 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) 16. In England and Wales, the newly professionalised (and ambitious) coroners’ officers see themselves as expert at this work; they aim to have a monopoly and will probably succeed under the new regime. Do we need something similar, or is there an option, cheaper, yet as effective? Who would employ them? One concern raised is whether retired police officers are appropriate individuals to fulfil this role or if this is something where we require a greater degree of independence. Removal 17. If the PF is to assume a more hands on role should a local/national removal service exist? It has been stated that the role of COPFS is outwith the remit of this group but it is difficult to see how consideration of interaction with the Fiscal can be avoided. At the present time there exists considerable variation between different areas with a number of ad hoc arrangements where there is varying success but it would surely be better to have greater consistency so that audit may more quickly pick up statistical ‘outliers’. Currently, most removals are by contracted funeral directors (at police expense) where the cause has been ruled unknown or police enquiries are in progress. 18. Action: ascertain present costs for these services and identify potential rationalisation. 19. Problems: as always, the demographics and geography of Scotland militate against a one size fits all solution; ways have to be found to engage the Crown Office representative in at least considering change. Further examination 20. Autopsy is the traditional answer to doubt, but cogent arguments were advanced by expert witnesses at the Shipman Seminars in favour of considering a greater depth of preliminary investigation or the use of non-invasive techniques. However, pathologists have voiced reservations on the accuracy of e.g. MRI scanning. One also has to bear in mind that as a proportion of deaths, fewer autopsies are performed in Scotland as opposed to England & Wales. Religious sensitivities formed an important backcloth to these considerations. 21. Action: research present state of scanning techniques applicable to a cadaver and the resource implications. 22. Who is to conduct in depth, non-PM, investigation? It is insufficiently recognised that identification of pathological processes is not necessarily evidence of the (medical) cause of death. Documentation 23. Smith proposes a lengthy, multiple-part, certificate. She expects it be used for all deaths. That its completion demands time and trouble may be a virtue, but tick boxes are not always properly considered. Relevant audit with an evidence basis undertaken in a systematic way would appear a better way of addressing this issue. 24. Action: ascertain the proportion of unsatisfactory certificates questioned by registrars. The present death certificate book is awkward to use (portrait style of counterfoil). Page 4 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) 25. Problem: any new certificate would have to comply with WHO and possible European requirements? Informants 26. For registration purposes, these are identified on the back of the death certificate. Smith envisages that informants will be available as interested parties in the circumstances of the death. The reality is that many people die alone or unexpectedly, without informants of this kind. It is not clear how this defect (and it is a defect) ought to be approached. Families ought to have confidence in the system, but what if there is no family interest? Background GP/hospital records 27. At the present time, the ‘first’ doctor [police surgeon if that is the local practice, and the medical referee in the case of cremation] has no access to records of either type. If the certification process is to be robust, this is a minimum requirement. This current inability to view the deceased’s GP and hospital records significantly hampers more accurate death certification. The disadvantage of viewing this material pending more widespread development of electronic records is that there will be an inherent delay in being able to offer the necessary certificate. 28. Problem: how can this be accomplished without the allocation of substantial time? Is it to be part of the definitive reporting to the registrar/PF? Is this a job for a new breed of doctor (displaced referees or police surgeons willing and able to spend the necessary time at substantial cost?) Carers 29. See ‘informants’ above. Suspicious circumstances Preservation of locus 30. This depends upon the expertise of the initial certifier in reading the locus. There will be a small number of deaths where one cannot readily rule out prima facie evidence of foul play until the result of the autopsy is available and the locus requires to be preserved until preliminary results are available. Although there will be a relatively minute number of deaths where there is actual criminality, the importance of these to society is such that any replacement system has to be at least as robust as the existing arrangements in this respect. 31. Action: consider the functions of coroners’ officers (see above). The initial certifier must have a means of handing over matters to a competent person immediately, and ensuring that the locus is preserved, even when the difficulty relates to cause of death, rather than suspicious circumstances. 32. Problem: we have not identified the personnel to assume these varied functions. CID/SOCO Page 5 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) 33. There is no question of the primacy of the police/PF whenever suspicious circumstances are identified. Potential certifiers have to stand back for expert scene of crime examination. PM 34. Fiscal PMs are performed mainly under contract with CO. 35. Action: ascertain the pattern of ‘sudden death’ autopsies and the interval before bodies are released; the place of ‘view and grant’ examination and who should undertake these; the adequacy of department size; qualification and skills of forensic pathologists in Scotland. 36. One also has to realise that there is considerable variation in practice depending on the geographical area and it should surely be possible to ensure a greater degree of uniformity in the way sudden deaths go forward to autopsy. 37. Hospital autopsies are few in number; has this affected expertise? Anecdotally there are cases where autopsy was performed by a hospital pathologist at the instance of a PF, yet the cause has not been identified four months later. 38. Problem: in a small country, the pool of pathologists is tiny and of particular expertise at vanishing point: how can this be squared with Smith’s insistence that, for example, only specialist paediatric pathologists autopsy children dying of alleged neurological trauma? 39. In Scotland we rightly insist on corroborated evidence and there should be no relaxation of this principle with revision of the system. Disposal of body Certification 40. One unified certificate for death and cremation purposes ought to suffice, whatever the manner of lawful disposal. There would appear to be a distinct advantage in retaining involvement of the general practitioner as one of the signatories where the deceased has died in the community and the doctor feels professionally able to complete the required certification. Clearly, they have to be comfortable that they are in a position to comply with the General Medical Council’s requirements as stipulated in Good Medical Practice. 41. Action: ascertain how readily information can be transmitted from medical centres or hospitals to the certifying authority. 42. There would appear to be an acceptance that the current system whereby three doctors are involved in the cremation may be decreased to two, one of whom is the GP. That being said, one doctor may suffice so long as there is adequate supervision and audit, even although this must be post hoc. Clearly, the certifier must have proper support in administrative terms. This is not an early career position, but nor must it fall into the hands of retired doctors seeking a sinecure. Although it is obviously not obligatory to have an identical system to that pertaining in England and Wales it would be curious to Page 6 of 7 PAPER 3 B&C Review Group 16 May 2005 (DRAFT) deviate significantly from the arrangement in these countries when there is regular cross border transfers of deceased persons. 43. Problem: all systems proposed must entail substantial delay, even if a corps of doctors stands by 24 hours a day to do the investigation; it may not be desirable (or necessary?) for certifying doctors to have unlimited access to a person’s full medical history and it is a well established ethical precept that a doctor’s duty of confidentiality extends beyond death. Page 7 of 7