Modern scholars generally agree that Western philosophy began

advertisement

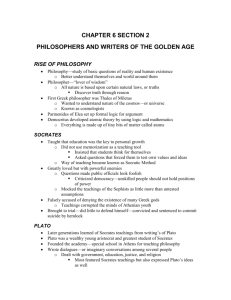

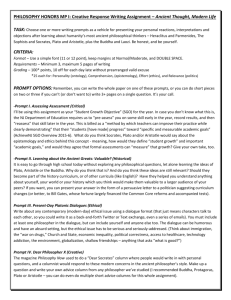

Name: ________________________________ Greek Philosophies Socrates, Plato, & Aristotle Modern scholars generally agree that Western philosophy began with the Greek thinkers of the ancient world. Suggesting indebtedness to the Greeks, the word "philosophy" comes from Greek word philosophos, meaning "love of wisdom." However, modern philosophy does not necessarily share the same beliefs as the ancient Greeks. On first encounter, many modern readers may find Greek beliefs naive or downright bizarre, but contemporary desire for wisdom and an approach to attaining it owes much to the methods laid down by those ancient thinkers. The first important step those philosophers took was to ask such questions as, What is the nature of the world? What is the nature of man? Do we perceive the world as it actually is, or are we seeing just a reflection of an underlying reality? By asking those kinds of questions and attempting to answer them logically, the Greeks laid the foundation for Western intellectual history. There is not one set of beliefs that can be called "Greek philosophy." Rather, the term refers to a set of very different arguments put forth by thinkers in disparate times and places. In addition, Greek philosophy was not dedicated entirely to questions that may be considered "philosophy"—that is to say, the study of morality and human existence. Many of the earliest Greek philosophers primarily considered subjects that modern thinkers would consider science, mathematics, or political theory. Ancient Greek philosophers did not tend to limit themselves to particular fields of study but rather addressed diverse subjects that they found most interesting or relevant for advancing knowledge. In the fifth century, Athens began to become the center of Greek philosophy. Its victories in the Persian Wars and its leadership of the Delian League eventually made it the economic and cultural capital of Greek civilization. In the mid-fifth century, Greek philosophy reached a turning point with the career of Socrates, who steered philosophical investigations toward an examination of humanity and human behavior. His teachings remain somewhat inexact because Socrates never wrote anything down. He believed firmly that philosophy should be conducted through discourses between learned men, and he founded a school in that vein. At his school, he and his students pursued a greater understanding of truth through probing conversations and sought to reject accepted doctrines unless they could be proven. Socrates' overriding principle was that we must continually question all of our beliefs; he characterized himself as a gadfly for the Athenian people because of his insistence on intellectual self-examination. However, other scholars, including the philosopher Plato, painted a very different picture of Socrates. What became clear was that his teachings aroused the anger of many conservative Athenians, who brought him to trial for spreading impious thought and for corrupting the city's youth. In 399 B.C., Socrates was convicted of impiety and sentenced to death by hemlock poison. Through the writings of his student Plato, Socrates' philosophical influence grew far greater after his death. Plato, who founded the Academy, is by far the most widely read Greek philosopher today—in part because near-complete versions of many of his works exist, as opposed to very limited fragments from many other Greek philosophers. Plato's work has been appreciated for its sophisticated arguments and robust literary style that have intrigued readers for more than 2,000 years. His works often take the form of dialogues between men who take opposing positions on issues of morality, aesthetics, or government. One of his most vivid concepts was his characterization of human nature as a chariot pulled by two horses—one horse represented such wild, base instincts as greed and sexual desire, while the other represented such loftier emotions as love. The driver, who represented human will, must steer a course between those constantly opposing forces in the human spirit. Another of Plato's ideas is the theory of Forms, in which he argued that the perceived world was not reality itself but rather a series of reflections of ideal forms that exist at a more basic level. To illustrate that concept, he suggested in "The Allegory of the Cave" that reality is like the perception of a person in a cave who sees only the shadows of what is occurring on the outside. Plato's most widely read work today is the Republic, which presents a utopian society ruled by philosopher kings, who eschew all material riches in order to protect their minds for service to the state. Modern readers arrived at widely differing interpretations of the work, ranging from an endorsement of totalitarianism to arguments for the equality of the sexes. Plato's greatest influence came in the structure of his arguments. His dialogues established a precedent for the Socratic method, in which two or more people come to a greater understanding of the truth by examining all angles of a question and using unflinching logic to arrive at the best answer. While Socrates may have invented the style, contemporary scholars' understanding of it is derived from Plato's dialogues. The impact of that style of argumentation on philosophy, the law, and many other disciplines of study has been enormous. While Plato is viewed as the most influential philosopher today, his student Aristotle was by far the most influential philosopher during the Middle Ages. Aristotle's work displayed, perhaps, the most ambitious scope of any scholar in history. He and his students attempted to compile authoritative works on ethics, government, literary theory, physics, zoology, ethnography, and logic. Although he began his career at Plato's Academy, he eventually founded his own school, the Lyceum, where his students sought to compile and synthesize the work of all the thinkers who came before them, including Thales, Xenophanes, and Pythagoras. In his study of governments, Aristotle had his students gather hundreds of constitutions from cities throughout Greece in order to determine which form of government was best. Although he was an original thinker in his own right, Aristotle's genius came more through the rigorous logic he applied to synthesizing the three centuries of knowledge and ideas that preceded him.