Ions in Channels - Physicochimie des Electrolytes et Nanosystèmes

advertisement

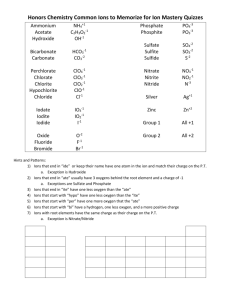

Laboratoire PECSA - Physicochimie des Electrolytes, Colloïdes, et Sciences Analytiques - UMR 7195 UPMC/CNRS/ESPCI SEMINAIRE Pr. Bob Eisenberg Department of Molecular Biophysics and Physiology Rush Medical College, Chicago Ions in Channels Lundi 4 mai 2009 à 14h30 A la bibliothèque du laboratoire PECSA Université Pierre et Marie Curie Bâtiment F/74 – 7ème étage – porte 754 4, place Jussieu – 75005 Paris Jean-François DUFRECHE Laboratoire PECSA Case 51, Université P. et M. Curie, Bat F74, Pièce 757 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 PARIS CEDEX 05, FRANCE E-mail : jean-francois.dufreche@upmc.fr Tel: (33 1) 44 27 22 03 Fax:(33 1) 44 27 32 28 Ions in Channels Bob Eisenberg Department of Molecular Biophysics, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL 60612 USA, E–mail: beisenbe@rush.edu Channels are proteins with a hole down their middle that control a wide range of biological function because they control the flow of ions and thus electric charge in and out of cells: channels produce the electrical properties of the nervous system; they control the heart beat and muscle contraction; channels control secretion of hormones and urine. A substantial fraction of drugs act on channels. Thousands of biologists study channels every day, recording current voltage (IV) relations from single molecules in a variety of solutions and concentrations. The genetic code and amino acid sequence for hundreds of channels are known, and new three-dimensional structures are reported every few months. Ion channels are appealing objects for physical investigation because conformation changes are not involved in channel function, once the channel is open. Ions move in a structure that does not vary even by 0.1Å on the biological time scale of 105 sec. Open channels are appealing objects for chemical study because they effectively select among chemically similar ions, under unfavorable circumstances. Channels are appealing objects for physical study because they contain an enormous density of charge, fixed, mobile, and induced. Channels are lined with a large density of induced and fixed charge, say 4 charges in a length of 20 Å, diameter of 5 Å, with a nearby ionic atmosphere of 10M concentration (typical biological solutions have ionic concentrations ~200 mM and water ‘concentrations’ ~55M; ions/molecules that control proteins and channels typically work at ~106 M concentration). Direct simulation of channel behavior is difficult if not impossible, because ion transit takes 10 nsec; concentrations of 106 to 55M must be accurately represented in the same calculation, and macroscopic electric fields and concentration gradients produce substantial flows, making equilibrium analysis unhelpful. Lower resolution theories are surprisingly successful in describing selectivity and IV relations: mean field treatments do quite well if they include electric field, crowded charge, and induced charge, although the proper treatment of correlated motions (e.g., plug flow of molecules in a single file) is a challenge. The future seems to require simulations to evaluate parameters and establish bounds of validity for lower resolution theories. Simulations are more helpful if they are calibrated in standard situations and thereby shown to deal reliably with crowded charge, electrostatic fields, and induced charge away from equilibrium.