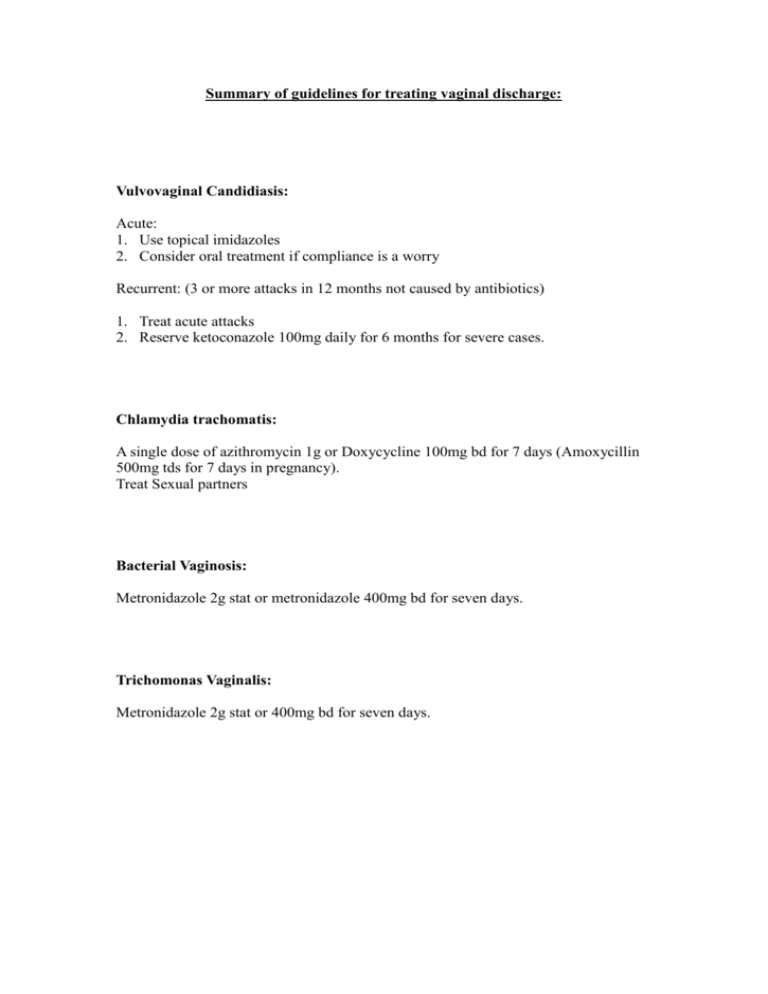

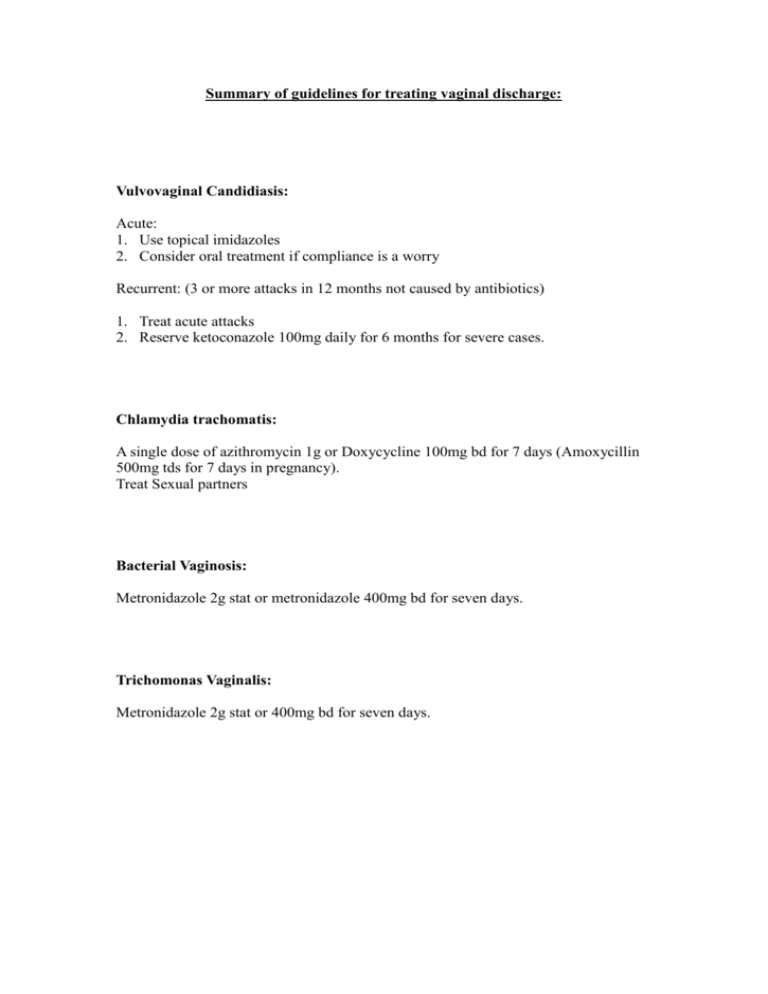

Summary of guidelines for treating vaginal discharge:

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis:

Acute:

1. Use topical imidazoles

2. Consider oral treatment if compliance is a worry

Recurrent: (3 or more attacks in 12 months not caused by antibiotics)

1. Treat acute attacks

2. Reserve ketoconazole 100mg daily for 6 months for severe cases.

Chlamydia trachomatis:

A single dose of azithromycin 1g or Doxycycline 100mg bd for 7 days (Amoxycillin

500mg tds for 7 days in pregnancy).

Treat Sexual partners

Bacterial Vaginosis:

Metronidazole 2g stat or metronidazole 400mg bd for seven days.

Trichomonas Vaginalis:

Metronidazole 2g stat or 400mg bd for seven days.

Guidelines for the management of vaginal discharge

Background

Vaginal discharge accounts for approximately 7% of all GP consultations. It may be

physiological or pathological.

Physiological discharge - comprises secretions of the Bartholin's gland and the

endocervix with cells shed from the vaginal walls. These secretions are affected by

hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle. Cervical ectropions, the intra uterine

contraceptive device and the combined oral contraceptive may increase physiological

discharge. The pre-pubertal and postmenopausal vagina, as they are not well

oestrogenised are more prone to infection.

Pathological discharge - In women of reproductive age, pathological discharge is

usually caused by infection and causative organisms may or may not be sexually

transmitted.

In pre-menarcheal girls - threadworm infestation, intra-vaginal foreign bodies or

sexually transmitted diseases can cause pathological discharge.

In post- menopausal women atrophic vaginitis predisposes to trichomonas infection

and bacterial vaginitis.

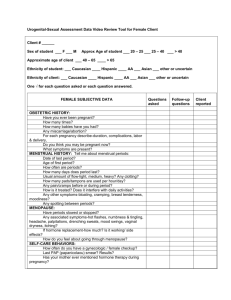

History

Patients will complain of a vaginal discharge. The history should establish the

likelihood of pathological discharge. Ask about:

the nature of the discharge (colour, smell)

associated symptoms e.g. itch

abdominal pain

associated with periods

sexual contacts

inter-menstrual or post-coital bleeding

Examination

Technique:

Pelvic examination with palpitation of vaginal nodes and inspection of the genitalia

for evidence of vulvitis, warts, infestation or ulcers.

Speculum examination with high vaginal swabs taken for trichomonas and candidiasis

and endocervical swabs for gonorrhoea and chlamydia (in sexually active women).

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis:

25% surgery visits for vaginitis

75% of women will develop vulvovaginal candidiasis at some time.

50% will have at east one recurrence.

Predisposing factors:

antibiotic use.

High oestrogen oral contraceptives

Diabetes mellitus

Pregnancy

IUCD use

HIV infection.

Acute vulvovaginal candidiasis: (Reef et al 1993)

The Imidazoles, (Clotrimazole and Miconazole) have higher cure rates than

nystatin, (80-90% compared with 70-90%) in trials comparing 14 days treatment.

Oral therapy is only as effective as topical treatment in non-pregnant women.

Oral treatment can be associated with GI symptoms and headache and there are

important interactions with drugs such as terfenadine, rifampicin and phenytoin.

Adverse reactions with the oral Imidazoles uncommon but still around 6% for

itraconazole, 10% for ketoconazole and 5-12% for fluconazole.

Ketoconazole has a risk ofidiosyncratic hepatitis of 1:15000.

Recommendations:

3. Use topical imidazoles first

4. Consider oral treatment if compliance is a worry

Acute vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnancy: (Young and Jewell, 1995)

Imidazoles are more effective than nystatin

Treatment for 4 days is less effective than treatment for 7 days

Treatment for 7 days is no more or less effective than 14 days.

No risk of teratogenicity identified.

Minimal systemic absorption

Recommendations:

1. Use topical imidazole for seven days

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis:

Uncommon, only 5% of women who get vulvovaginal candidiasis.

No identifiable risk factors.

Optimal treatment is not yet determined.

Important to establish the correct diagnosis – exclude other causes of vaginitis.

Not associated with invitro-resistance to imidazoles.

Defined as 3 attacks in 12 months not associated with antibiotic use.

Acute attacks should be treated as any other.

There is no benefit in treating sexual partners.

Prophylaxis:

Ketoconazole has been studied both as a continuous treatment and cyclical.

(Sobel, 1986, Fong et al 1993)

100mg is as effective as 200mg

100mg daily for 6 months – 95% attack free at 6 months

and 50% at 12 months

with intermittent use attack rate high after cessation of

prophylaxis and 50% recurrence within 6 months.

Clotrimazole, monthly use, attack rate slightly reduced but study only for 3

months.

Recommendations:

3. Treat acute attacks

4. Reserve ketoconazole 100mg daily for 6 months for

severe cases.

Chlamydia:

Azithromycin is as effective as Doxycycline and in a cost-effectiveness analysis

(Bandolier, [28-4]) a single dose of azithromycin 1g; even though costing 4 times

more than Doxycycline 100mg twice daily for 7 days was more cost effective because

of better compliance giving reduced pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic pain, ectopic

pregnancy and tubal infertility. (treating chlamydia positive women with azithromycin

would save 4x as much as the additional cost.). Partners should be treated

simultaneously.

In pregnancy: (Brocklehurst and Rooney, 1996)

Amoxycillin is as effective as erythromycin in achieving microbiological cure.

Clindamycin and azithromycin may be considered further alternatives.

Further studies are required to ensure that microbiological cure with

amoxycillin translates into clinical benefit for mother and neonate.

Bacterial Vaginosis: (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 1998, Joesoef and Schmid,

1995)

With current treatment 50% of patients will relapse 4 weeks after treatment

Standard treatment is metronidazole orally, either 400-500mg twice daily for 7

days or 2G stat.

There is no benefit in treating the sexual partner

Intravaginal preparations of metronidazole or clindamycin appear as effective, (or

ineffective!) as oral treatments.

Bacterial vaginosis is associated with preterm birth and infective complications

following gynaecological surgery.

Pregnant women with a history of second trimester foetal loss should be screened

for bacterial vaginosis and if this is positive given oral metronidazole early in the

second trimester.

Women undergoing termination of pregnancy and known to have bacterial

vaginosis should be given metronidazole 1g rectally to prevent postoperative

infection and if testing is not available then should be given routinely.

Trichomonas Vaginalis:

Nitroimidazoles are effective in achieving short time cure (Metronidazole).

Single dose metronidazole (2G) is as effective as 400-500mg bd for 7 days.

Treat partners.

Severe symptoms may be helped by intravaginal nitroimidazoles.

Guidelines produced by:

Sheena McMain

Shirley Brearley

Rod Sutcliffe

John Potter

Steve Holmes

Adrian Dunbar

Simon Towers

June/July 1998

References:

Bandolier [28-4] Chlamydia STD treatment

Brocklehurst P, Rooney G, (1996) The treatment of genital chlamydia trachomatis

infection in pregnancy. In: Neilson J, Crowther C, Hodnett E, Hofmeyr G (Eds)

Pregnancy and childbirth module of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

[updated 2 December 1997]. Available in the Cochrane Library [Database on disk and

CDRom]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 1998.

Updated Quarterly.

Drug and therapeutics bulletin (1998) Management of Bacterial Vaginosis. Drug and

therapeutics Bulletin; vol. 36 No 5: May 1998

Fong I, Bannatyne R and Wong P. (1992) Lack of in vitro resistance of candida

albicans to ketoconazole, itraconazole and clotrimazole in women treated for

recurrent vaginal candidiasis. Genitourinary Medicine; 69: 44-46

Joesoef M and Schmid G. (1995) Bacterial vaginosis: review of treatment options and

potential clinical indications for therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases; 20

(supplement 1): S72-9

Reef S, Levine W, McNeil M, Fisher-Hoc S, Holmberg S, Derr A, Smith D, Sobel J,

Pinner R, (1995). Treatment options for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clinical Infectious

Diseases; 20(supplement1): S80-S90.

Sobel J, (1986) Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med; 315: 1455-8

Young G, Jewell M, (1995) Topical treatment for vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. In:

Neilson J, Crowther C, Hodnett E, Hofmeyr G (Eds) Pregnancy and childbirth module

of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, [updated 2 December 1997].

Available in the Cochrane Library [Database on disk and CDRom]. The Cochrane

Collaboration; Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 1998. Updated Quarterly.