Leibniz`s two-pronged dialectic

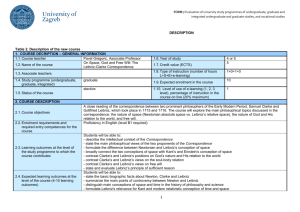

advertisement