Jeanne Roland. Leibniz et l`individualité organique

advertisement

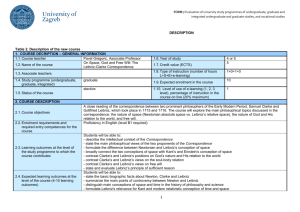

Jeanne Roland. Leibniz et l'individualité organique. Collection Analytiques, 99. Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2012. Pp. 380. Paper, $39.95. Jeanne Roland offers in this book a rich and thorough investigation of Leibniz’s metaphysics of living beings – what she terms organic individuality. The book is organized in three main parts and the main concepts under investigation, as well as the periods (or moments, in Roland’s terminology), can be presented as follows: In the first part of the book Roland focuses on “individual substance, corporeal substance and organic body in the years of the Discourse on Metaphysics”; in the second part, she is focusing on the transition in Leibniz’s writings from the notion of an individual substance to that of an organism; in the third part, she is focusing on monads, organic bodies, and individuals in the Monadology and other late texts. Roland does not attempt an exhaustive analysis of Leibniz’s texts. She is wisely focusing instead on the moments where Leibniz’s effort to think the metaphysics of individual substance, truly distinct from Cartesian dualism, engages the nature of living bodies (page 16). In particular, the main moments that constitute the structure for Roland’s book are (i) the years of the Discourse and the correspondence with Arnauld; (ii) the New System of Nature (1695) where the central notion is that of a natural machine; the New Essays, the exchange with Lady Masham and the exchange with Stahl regarding the notion of organism; (iii) the Monadology and the correspondence with des Bosses. This thematic focus and choice of texts makes a lot of sense in tracing (and reconstructing) the main steps Leibniz takes from the Discourse of Metaphysics to the Monadology. It seems to me that some of the inspiration for this kind of investigation, as well as for some of the main claims Roland advances, relate to Michel Fichant’s work and especially the introduction to his edition entitled From the Discourse on Metaphysics to the Monadology. This is a very welcome and interesting project, which was not carried out before in such detail and in such a textually informed manner. The merits of Roland’s approach can be exemplified through her investigation of Leibniz’s notion of a natural machine. Roland points out that the main features of this concept take shape in the years of the Discourse but that it is only in the New System (1695) that Leibniz delineates the boundaries between natural machines and artificial ones. Roland argues that the progressive disappearance of the term “individual substance” between the correspondence with Arnauld and the publication of the New System does not indicate that Leibniz has abandoned his concern for individuals and individuality as a necessary condition for true being (262). Rather, Leibniz’s thought has developed by thinking about the individuality of true unities in terms of a kind of machine – a natural machine, which is defined through an internal law of order and which also captures Leibniz’s paradigmatic example of living beings as animals which are taking the place of corporal substances. In this sense, the notion of a natural machine takes the place of the individual substance of the Discourse. I think that this is a very insightful observation. How this concept works with the definition of true beings in terms of monads of varying degrees of perfection is a question Roland addresses in the third part of the book. This book is a fine example of what might be characterized as the French school in Leibniz’s scholarship. To begin with, the book discusses Leibniz’s notion of living things through (the notion of organic individuality) in a metaphysical and historical context – this theme has been pioneered by François Duchesneau and has been almost ignored in the Anglophone world until quite recently. Gladly, this is rapidly changing. Second, Roland’s approach is primarily textual and it is extremely well informed as such. Third, Roland employs a developmental approach to the texts along the lines one finds in the writings of Michel Fichant. For these reasons, Roland’s conclusions might seem more local and particular to the texts and the period under consideration; she is more concerned with an adequate analysis of the texts than with a global thesis that risks simplifying them. Thus, her book does not advance a grand thesis but offers a careful and instructive story of Leibniz’s chronological and conceptual development through the complexity of his texts. This is not the place to attempt a comparison between the French school and the Anglophone school of doing history of philosophy. For readers who might ask themselves whether reading a book in French is worth their while, the most pertinent point is this: for any Leibniz’s scholar, this book offers a wealth of information and insights into Leibniz’s approach to the metaphysics of organic beings. It is a highly recommended read. Ohad Nachtomy ohadnachtomy@mac.com Bar-Ilan University