Study Questions for Leibniz: Discourse on Metaphysics

advertisement

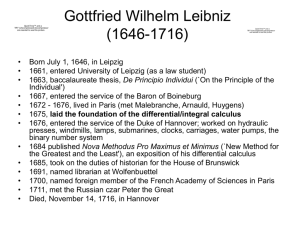

Study Questions for Leibniz: Discourse on Metaphysics. 1646- 1716. Leibniz was a brilliant mathematician, statesman/diplomat, educator, and all-around intellectual heavyweight. He may be the last person in the western tradition who had a good grasp of all of current science (not to mention the broader culture). But he left most of his philosophical work unpublished, and advocated an extremely strong position on theodicy (holding, contrary to both Descartes and Spinoza, that this is the best of all possible worlds and that God’s goodness is chiefly concerned with the well-being of spirits, i.e. our souls…). The doctrine that this is the best of all possible worlds led to Voltaire’s devasting satirical take on him, as Dr. Pangloss in Candide. 1. What is a monad? 2. Why do numbers not ‘permit of’ perfection? 3. What is wrong with the view that ‘the works of God are good only through the formal reason that God has made them’? 4. Who is it Leibniz has in mind when he describes those ‘who hold that the beauty of the universe and the goodness we attribute to the works of God are chimeras of human beings who think of God in human terms’? 5. What is wrong with the idea that ‘that which God has made is not perfect in the highest degree’? 6. What is the sophism of the ‘lazy reason’? 7. Why is Leibniz confident that the ‘felicity of the spirits is the principal aim of God’? 8. How does Leibniz reconcile talk of the simplicity of God’s way with talk of its richness and abundance? 9. How does this apply to God’s choice of which world to ‘create’? 10. How does Leibniz defend the claim that even miracles are part of the regular order of the world? 11. How does God manage to turn bad actions into (overall) good things? 12. How much does the full concept of a subject contain, with regard to the predicates that do (or will) apply to it? 13. How much does it contain, with regard to everything that goes on in the universe as a whole? 14. To what aspect of bodies does Leibniz want to apply the notion of ‘substantial forms’? 15. How do they (mere bodies, that is) differ from intelligent souls? 16. How does Leibniz reconcile the notion that there is a reason for everything with the claim that some things are contingent? 17. How does Leibniz distinguish truths that are necessary from those that are merely certain (true because of God’s free choice to produce the best of all possible worlds)? 18. How do substances manage to represent the same universe without acting on each other directly? 19. What is the ‘real story’ behind the (everyday) claim that one substance has a causal effect on another? 20. What is the real cause of our thoughts and perceptions (which are all that can really happen to us)? 21. What makes the difference between a substance that ‘causes’ some effect in another, and the substance that (passively) suffers that effect? 22. Why are miracles unpredictable (in a way that ordinary events are not)? 23. What is the difference between our essence and our nature, for Leibniz? 24. How would we express, today, the ideas of ‘force’ and ‘quantity of motion’ discussed by Leibniz here? 25. What makes force something ‘more real’ than quantity of motion? 26. How does Leibniz reconcile the use of final and efficient causes in physics? 27. What is the difference between a nominal and a real definition? 28. What is adequate knowledge? 29. How does Leibniz explain our own responsibility for our sins (and good deeds) (How does he reconcile this with the fact that ‘this man will assuredly do this sin’?) 30. How does Leibniz explain the relation between mind and body? 31. What is the man difference between spirits and other substances? 32. Why does Leibniz say that spirits reflect God while ordinary monads reflect the world? 33. Why has God ‘ordained that … spirits… shall… preserve forever their moral qualities’?