referent2

advertisement

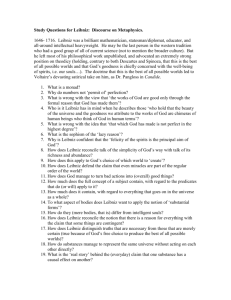

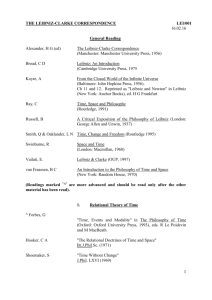

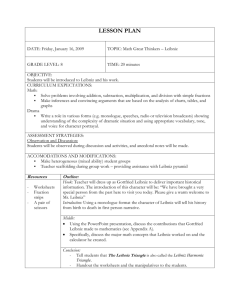

One can distinguish three distinct positions concerning the relationship between language, thought and reality. In colloquial terms, they may be called the mould theory, the cloak theory and the functional theory respectively. The mould theory represents language as an independent variable that functions like a sort of mould in the sense that it determines (conditions?) how thought categories function and in fact the kinds of categories in which thought can be cast. Moreover, it maintains that reality as such has no absolute objective ontological structure, and that it is the categories of language that condition how the world is perceived. In other words, it argues that there is no ultimate objective reality that we can talk about in meaningful terms at all. Rather, reality is always reality-as-perceived, and how it is perceived is a function of the categories of thought – which in turn are functions of the categories of language. In other words, it is sort of like Kant’s theory except that instead of making the categories of thought primary, it makes the categories of thought secondary to the categories of language. By contrast, cloak theory makes the categories of thought primary. It agrees that reality is always reality-as-perceived, and that reality in-itself has no ontological structure. Instead, we impose the structure onto reality by the categories of thought, and the categories of language are parasitic on the categories of thought – which are primary. In that sense, a cloak theory construes language like a cloak that conforms to and captures the categories of thought of its speakers. Therefore it is much closer to what Kant said: The categories of the understanding (of thought) condition that ontological nature of reality and condition the categories of language. Finally, there are functional theories of language. These theories – in a sense they are similar to certain views held by behaviourists – hold that language and thought are functionally related, and in turn are functionally related to the ontological that we see as constituting reality. According to this stance thinking is a phenomenon (if one can talk that way at all) that has to be explained entirely in terms of speech acts. In that sense, thought and language are one and the same. Therefore the notion of thought actually plays no role other than thought-in-the-context of a language act. There is no non-verbal thought, and certainly no translation from thought into language. Moreover, this sort of theory argues that ontology is functionally related to language (and hence to thought-aslanguage) while at the same time language is also affected by what the language is about. They condition each other. This seems to be the behaviourist approach that we find expressed in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. What I have called “mould theory” is probably best expressed by Benjamin Whorf when he said that:1 We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds - and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds. We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely 1 Whorf, B. L. 1940. "Science and linguistics". Technology Review 42: 227-31, 247- 8 because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way - an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language. The agreement is, of course, an implicit and unstated one, but its terms are absolutely obligatory; we cannot talk at all except by subscribing to the organization and classification of data which the agreement decrees He was here merely echoing what his teacher Sapir had stated when, in a classic passage, the latter claimed that2 Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society. It is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection. The fact of the matter is that the 'real world' is to a large extent unconsciously built upon the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached... We see and hear and otherwise experience very largely as we do because the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is a mould theory of language. It ultimately includes the claim that thinking is determined by the language, and that therefore people who speak fundamentally different languages think differently about the world – and possibly perceive the world differently. This, supposedly, also explains why translation from of language into another is often very difficult because “something is lost in translation.” The importance of what is lost in translation varies, of course. However, a good expression of this position can be found in the claim of Pablo Neruda who wrote in Spanish and who maintained that the best translations of his own poems were Italian (because of its similarities to Spanish), but that English and French are not good for translating his poetry because they “do not correspond to Spanish - neither in vocalization, or in the placement, or the colour, or the weight of words.” As he said, “It is not a question of interpretative equivalence. No, the sense can be right, but this correctness of translation, of meaning, can be the destruction of a poem. In many of the translations into French - I don't say in all of them - my poetry escapes, nothing remains. It does not say the same thing that I have written. It is obvious that if I had been a French poet, I would not have said what I did in that poem, because the value of the words is so different. I would have written something else.”3 2 Sapir, E. (1929): 'The Status of Linguistics as a Science'. In E. Sapir (1958): Culture, Language and Personality (ed. D. G. Mandelbaum). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press 3 Plimpton, G. (ed.) (1963-1988): Writers at Work: The 'Paris Review' Interviews, Vol. 5, 1981. London: Secker & Warburg. Historically, the cloak theory goes back all the way to Leibniz (who borrowed the idea from the (medievals) who had argued that there are ultimate and absolute simples in the conceptual realm,4 that as the basic building-blocks of all concepts they constitute an “alphabet of human thought”5 and that all complexes tout court are but the result of logical combinations of these simples. These simples are ontologically perspicuous and reflect the logic of that of which they are names (for which they stand). Therefore in his eyes the task of constructing such a language reduced essentially to that of identifying these simples and of representing them by the appropriate linguistic expressions. Leibniz did he delude himself that such a task was easy. As he himself pointed out on several occasions, although there had to be such simples independent of human thought, these simples were not evident to direct inspection but could be reached only by dint of logical analysis.6 Furthermore, he argued that being logically simple, these entities could not be understood by analytic or definitional procedures but only intuitively or by means of analogy.7 This brings me to Leibniz's theory of definitions. He distinguished two kinds: real and nominal.8 The difference between them he characterized like this: Whereas nominal definitions merely contained characteristics whereby one thing could be distinguished from another without regard to the logical compatibility of the components, 9 real definitions satisfied both requirements. They had to delineate their concepts not merely consistently and fully, but also had to "contain the affirmation of a possibility."10 Since Leibniz also maintained that only non-contradictory concepts could function as premises of inferences, he held that only real definitions could function in that capacity.11 It follows from this that in Leibniz's eyes, every term ultimately is either primitive, unanalysable and indefinable or complex, definable and introduced by a definition12 where – and this is what marks it as a cloak theory - the logic of the terms reflects the logic of reality. However, this Leibniz also recognized other differences between the two 4 Gerhardt, Phil. IV pp. 44, 296, 423; Couturat, p. 514. 5 Gerhardt Phil. VII, p. 185 6 Cf. Erdmann (ed.), LEIBNIZ, Opera, pp. 93, 99, etc.; Parkinson, Leibniz's Logical Papers (Oxford, 1960, p. 4; Clodius Piat, Leibniz (Paris, 1915), p. 72. 7 Gerhardt, Phil. IV, pp. 423 ff.; VII, p. 295. 8 Cf. Gerhardt, Phil. VII, pp. 292 ff.; Couturat, p. 432 etc. 9 Cf. Couturat, p. 220. 10 Cf. Gerhardt, Phil. IV, p. 450. 11 Cf. Frege's position in his controversy with Hilbert. 12 Cf. Couturat, La Logique p. 184. kinds of terms. In fact, from the viewpoint of logic this was not a difference at all, since the logico-syntactic natures of definiens and definiendum had to be the same. The genuine and profound difference that obtained between was what he called the difference between substantial and predicative expressions respectively: between predicate expressions and proper names. The latter named "individual substances" or complete beings", and were said to be associated with a "concept so complete that it suffices to comprehend and render deducible from it all the predicates of the subject to which the concept is attributed."13 As to predicate-expressions, as examples of these he adduced property- and relation-terms, both of which were said to be associated with incomplete concepts and ontologically incomplete and dependent entities. Finally, the functional/behaviouristic approach to language is, s I said, more like what we find in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Language is functionally related to a way of life, and thought, language and reality do not constitute hermetically sealed and separate realms. Words are more than names. They have a function and that function is integrally tied to my way-of-life. What I think – how I think – is not a function of the language that I use but a function of the way of life which in turn is functionally related both to language and reality. Thought really drops out of the picture because it cannot play a role in learning the language. (See Strawson here, who argues that the criteria for use of words must be publicly learnable criteria.) Likewise, reality/ontology is not something given in itself by functionally related to how I am embedded in the world – which in turn is functionally related to the world itself. 13 Couturat, Opuscules, p. 403; Cf. GIRr:%km, Phil. II pp. 261 ff. et pass; VI, p. 289