Knowledge Transfer in Theory and Practice

advertisement

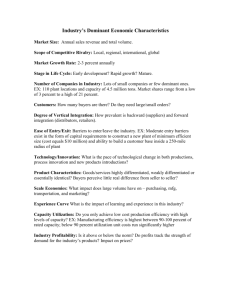

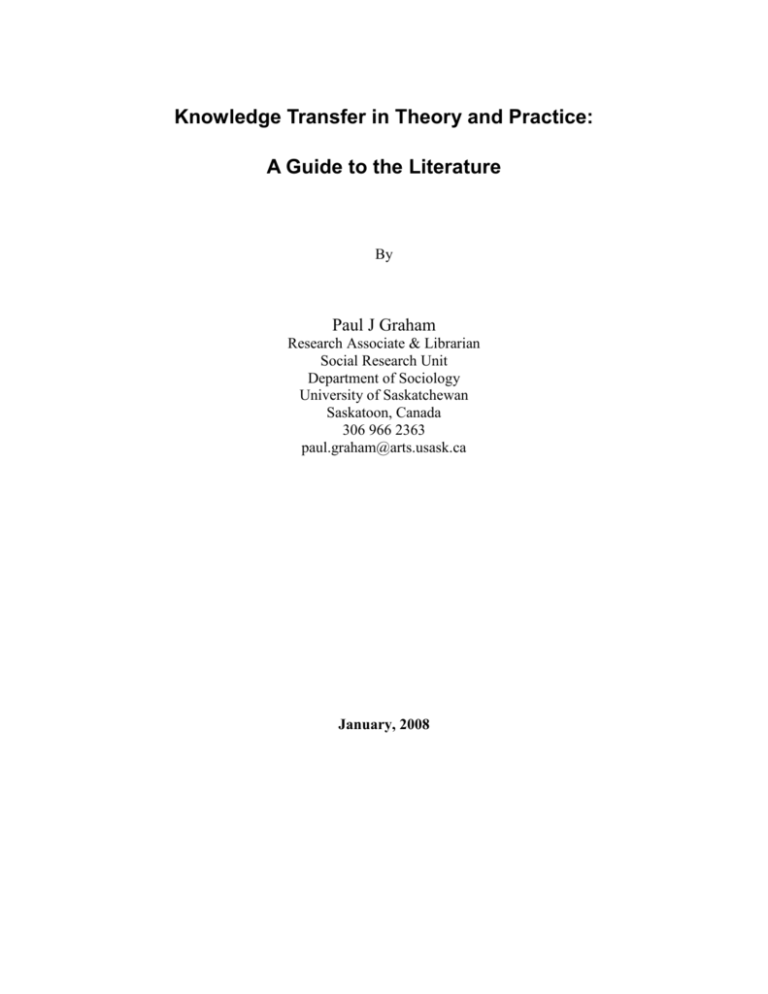

Knowledge Transfer in Theory and Practice: A Guide to the Literature By Paul J Graham Research Associate & Librarian Social Research Unit Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Canada 306 966 2363 paul.graham@arts.usask.ca January, 2008 Introduction Any basic Internet or database search for “Knowledge Transfer” (KT) provides a host of results: bibliographies, presentations, conferences and workshops, papers forthcoming, organizations, pamphlets and so on. More stunning than the breadth of material available on Knowledge Transfer is the variety and inconsistency of terminology used to describe it. Commonly used terminology include: transfer, translation, exchange, utilization, implementation, diffusion, distribution, management; as well as many combinations such as “research transfer”, “research utilization”, or “knowledge utilization”. This state of the literature causes special problems for information retrieval and organization; a range of vocabulary is being used. To compound the problem, there are few authority controls or thesauri for those interested in making sense of Knowledge Transfer when first beginning to investigate the subject.1 Very few databases have structured ways to cope with this growing field of study (and academic faculties do not maintain “Departments of Knowledge Transfer” in which professional groups can authoritatively professionalize the terminology and subject matter.) Authors can also add to the confusion by contextualizing their argument using one set of terminology, but at the same time, include many of the alternative uses (Thompson, Estabrooks & Degner, 2006). This terminological turmoil is only the first challenge; Knowledge Transfer also reflects a diverse set of contexts, goals and activities. This may include the improvement of government policy, dissemination of public health knowledge, or internal Knowledge Management in organizations. Knowledge Transfer professionals are found in health, social science, governance, as well as organizational contexts (such as the Institute of Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Utilization Studies Programme, or the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation here in Canada, to name a few). The field of health Knowledge Transfer, for example, has at least three distinct levels of analysis: 1) clinical level wherein new knowledge is applied to improve the lives of patients (forming a continuum with evidence based medicine); 2) managerial and policy strategies wherein decision making processes take place and; 3) educational level ensuring new medical 1 Authority control is a term from library and information science. It indicates the practice of using consistent terminology within a catalogue of resources. For example, Mozart can be accessed via W. A. Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart, or simply, Mozart. Therefore, librarians usually select one term to represent all variations. 2 professionals are learning evidence based techniques and understanding how to improve their application of knowledge over a lifetime. As well as being dispersed across different professional fields and contexts, Knowledge Transfer resources are guided by a plethora of theoretical approaches, models, and empirical studies. There are traditional models of knowledge application (Instrumental, Conceptual, Symbolic) and modern theories of knowledge application (Mode 2 Knowledge Production; Triple Helix; Post Normal Science). There is a continuing development of empirical studies providing justification for Knowledge Transfer strategies. Empirical studies may use specific Knowledge Transfer perspectives or measures (Stetler Model of Research Utilization; Diffusion of Innovation); they may also focus on empirically measuring transfer statistically (factor analysis of an already existing data set, for example). From this brief introduction a picture of Knowledge Transfer is forming; it is a growing literature with many different theories and models, contexts and goals, practices and measures. With such a large set of resources available, dispersed over many fields of interest, it is obvious then that guides or primers on Knowledge Transfer are a vital component in assisting researchers. This brief guide is meant to provide some clarification for all those professionals wishing to possess some conceptual guidance in Knowledge Transfer. This document is being framed within an information science perspective and the main focus is to provide researchers, practitioners, and other professionals with assistance in identifying and organizing the concepts of Knowledge Transfer. Structure of KT Guide The following report is divided into the following areas of concern: 1) the various search results that arise from using different Knowledge Transfer terminology; 2) the subject areas where we will find Knowledge Transfer has become mainstream; 3) the important roles found in Knowledge Transfer as they are performed by individuals or organizations; 4) Models and theories associated with Knowledge Transfer; and two brief sections on 5) Empirical methods and 6) Tools to assist the Knowledge Transfer process. 3 Section 1: Terminology As stated previously, Knowledge Transfer represents a myriad of different terminology: transfer, translation, utilization, management, etc. The terminology is reviewed by searching for these terms in ISI Web of Science database. Although any database will be limited, the Web of Science represents one of the best options for a comprehensive view of the terminology. However, for reliability and comparison, Scopus database will also be searched and inserted in tables for comparison. Knowledge Transfer General searches for “Knowledge Transfer” will retrieve a host of results, mainly surrounding issues of business, commerce, and technology. Although there are many examples of “Knowledge Transfer” in health2 (Kramer & Wells, 2005; Thompson, Estabrooks, & Degner, 2006), social science (Landry, Amara, & Lamari, 2001) and policy science (Crewe & Young, 2002) business issues do seem to be most evident when searching for knowledge transfer specifically. (A Google Scholar search reveals over 30, 000 results.) A Web of Science search retrieves 865 articles shown here in the following graph published by year: Figure no 1: “Knowledge Transfer” publications as charted by Web of Science 2 In many seminar presentations I have attended at the University of Saskatchewan on the topic of Knowledge Transfer, a clear message was communicated among health professionals: “Knowledge Transfer” was not felt as acceptable a term because it implied “one-way” transfer of knowledge. The health professionals did not want to engage in this type of process without a communicative process allowing dialogue among decision makers and clinicians. Some prefer “Knowledge Exchange”. 4 The majority of these items represent business and management dominated subject areas. The following results represent articles with the following subject areas. Due to multiple subject terms being assigned to any one article, the following results do not represent mutually exclusive records but rather a clustering of subject designations for this particular search. Table 1: Comparison of search for “Knowledge Transfer” in two databases Web of Science Database Management Business Operations Research & Management Science Information Science & Library Science Computer Science, Information Systems Scopus Database Business, Management and Accounting Engineering Computer Science Social Science Decision Sciences Count 274 142 78 60 58 Count 205 185 117 115 51 Business perspectives range from motivational aspects of workers (Burgess, 2005); training, patents, presentations (Argote et al., 2000); team based approaches (Wu et al., 2007); interfirm cooperation and cross-cultural exchange in the transfer of knowledge from one bureaucracy to another (Inkpen & Pien, 2006). One of the more popular concepts in the business context has been Szulanski’s “Sticky Knowledge” wherein the transfer of knowledge is viewed as a difficult process, which requires special strategies to harness tacit knowledge (see Szulanski 2000; 2003; Szulanski & Jensen, 2004). To add to the terminological confusion, this strategy is sometimes contextualized in the knowledge management literature (Szulanski & Cappetta, 2003). Carlile (2002) builds on Szulanski’s work by exploring knowledge transfer, mainly through the guise of knowledge management, with the exploration of “boundary objects” in business knowledge transfer. 5 Knowledge Translation A brief search for “Knowledge Translation” reveals another growing literature. As the graph in figure 2 (below) displays, “translation” has become popular to use in recent years. Figure no. 2: “Knowledge Translation” publications as charted by Web of Science The history of the phrase reaches back at least to the work of Beal (1980). Beal used the phrase “knowledge translation” as a vital component to a “communication system” within an agricultural context. Problems in this area of transfer and utilization can be identified as “deeply embedded in concerns with communications” (Beal, 1980: 4). “Knowledge Translation” appears again in the context of “technology transfer”. Grantham (1985) claims that critical to the discussion is the reframing of knowledge from the “knowledge translation” stage to product development stage. Recently, in Canada, the term “Knowledge Translation” has become a popular term used mainly within a health context. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and other health funding agencies, such as the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF), have contextualized their organizational documents and their funding requirements via “Knowledge Translation” thereby affecting scholar’s use of language (SHRF, 2007, CIHR, 2005). Special issues of Knowledge Translation can be found in the Journal of Continuing Education in Health Professions (Volume 26) as well as 6 Nursing Research (Volume 56, supplementary issue 1). Knowledge Translation is a good phrase to use when searching for health issues related to the transfer of knowledge. Consider the search results using the phrase “Knowledge Translation” in Table 2 (below): Table 2: Comparison of search for “Knowledge Translation” in two databases Web of Science Database Health care sciences & services Public, Environmental & Occupational Health Education, Scientific Disciplines Nursing Cardiac & Cardiovascular systems Scopus Database Medicine Nursing Biochemistry, Genetics & Molecular Biology Economics, Econometrics and Finance Health Professions Count 27 25 18 11 6 Count 35 9 4 3 3 Knowledge Utilization “Knowledge Utilization” (KU) represents a terminology with the most significant academic history. Although not as popular as other terminology today, Knowledge Utilization studies constitute the majority of work achieved prior to the early and mid 1990s. The most explicit attempt to address utilization, academically, started in 1979 with the publication of a new journal Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization (now called Science Communication). Although the Web of Science database is not comprehensive enough to capture the entire history of Knowledge Utilization, the following graph (Figures 3) reveals its history in comparison to other terminology. Utilization extends back as far as 1988 (in this database) and is punctuated by fluctuations in popularity over the years. This may be due to the emergence of the “information age” or “information super highway” during the late 80s and 90s when the surge and the demand for “information” and “information technology" over “knowledge” were paramount. 7 Figure no. 3: “Knowledge Utilization” publications as charted by Web of Science In the editor’s introduction of the 1979 journal Knowledge, Robert Rich writes that the purpose of this journal is to provide a forum for researchers, policy makers, and all others working in their own personal silos of knowledge, but perhaps not in full communication of each others progress (Rich, 1979). The journal articles range from the production and application of knowledge (Machlup, 1979; Zaltman, 1979) to issues of social responsibility and accountability (Nelkin, 1979). Rich also predicts the importance of interdisciplinary research as future development. (See also, Choi & Pak, 2006). The results (Table 3) show that interdisciplinary subject designations are primary. Table 3: Comparison of search for “Knowledge Utilization” in two databases Web of Science Database Social Science, Interdisciplinary Education & Educational Research Nursing Information Science & Library Science Management Scopus Database Social Sciences Engineering Medicine Business, Management & Accounting Nursing Count 22 16 11 10 9 Count 41 30 26 20 18 8 Historically, an early attempt to address Knowledge Utilization is present in a work by Guetzkow (1959) where the theme of “social engineers” is prominent for using social science information. Indeed, the topic of “social engineering” (sometimes negatively received) is being resurrected in relation to the transfer and utilization of knowledge for social benefit, especially in China (Chiang, 2001; Tomba, 2004).3 Knowledge Utilization research has addressed communication issues (Beal & Meehan, 1986; Beyer, 1997) and research methods (Yin and Gwaltney, 1982; Dunn, 1983a,b). (See also, Landry, Lamari & Amara, 2005). Knowledge Management Although sometimes overlooked when considering the Knowledge Transfer literature, Knowledge Management (KM) is also a field of study wherein much effort and resources are devoted to the storage, sharing and transfer of knowledge via technology and social processes. “The technology-focused understanding of knowledge management has since evolved into a more comprehensive view, one that acknowledges the importance of facilitating the social interaction of people (e.g. communities of practice) in order to share and retain knowledge” (Schroeder & Pauleen, 2007: 415). Other Knowledge Management papers suggest specific strategies commensurable with Knowledge Transfer. For instance, Hansen, Nohira and Tierney (1999) recommended focusing Knowledge Management efforts in either a personalized strategy (connecting people) or codification (connecting documents to people). The authors further claim that “to excel” in your management endeavour, you need to focus nearly 80% on one of the strategies, either the codification or personalization of knowledge. (In other words, you cannot fence sit; you must decide which one is more valuable to your organization.) This reflects earlier Knowledge Transfer suggestions for either moving people or moving information (Knott & Wildavsky, 1980; Yin, 1981). There are various ways in which the social component of Knowledge Management has been approached: Tacit Knowledge/Codification (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Munier & Ronde, 2001) 3 The Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan hosted a conference wherein Chinese scholars discussed resolving social health issues via social engineering. 9 Concept of “Ba” (Nonaka & Konno, 1998) Communities of Practice (Iverson & McPhee, 2002; Duguid, 2005) Epistemic culture (Knorr-Cetina, 1999; Styhre, 2003) Epistemic community/ies (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 2005) Learning Organization (Ortenblad, 2002; Scarbrough & Swan, 2003 ) Absorptive Capacity (Matusik & Heeley, 2005; Van den Bosch, 2003) One of the most important things to note about Knowledge Management is that there are many empirical studies. These studies are a valuable source of information for forming Knowledge Transfer strategies and selecting methodologies to measure effectiveness and impact, especially in business (Birkinshaw, Nobel & Ridderstrale, 2002; Bose, 2004; Chou & He, 2004; Bock et al., 2005). A comprehensive review of Knowledge Management papers that would account for all the different methodologies would greatly enhance understanding of Knowledge Transfer strategies. Although not specifically an information retrieval issue, it is also important to note the importance of Knowledge Management as a foundation to good Knowledge Transfer. Many issues of transfer rely on the technical and social components within your organization. Do you have a librarian or Knowledge Broker keeping people informed (see the section Knowledge Transfer by Roles)? Do you have information policies about access to information? Or, do you allow and foster the informal sharing of knowledge via face-to-face meetings or by using social networking software, such as Facebook? Figure no. 4: “Knowledge management” publications as charted by Web of Science 10 Table 4: Comparison of search for “Knowledge Management” in two databases Web of Science Database Management Computer Science, Information Systems Computer Science, Artificial Intelligence Information Science & Library Science Computer Science, Theory & Methods Scopus Database Computer Science Engineering Business, Management & Accounting Social Sciences Decision Sciences Count 642 618 519 499 385 Count 1, 397 1, 365 1, 057 691 368 Knowledge System The “Knowledge System” concept (referred sometimes as Knowledge-Based Systems) represents a more holistic Knowledge Transfer strategy. When considering a system perspective, Knowledge Transfer is organized into the discrete components of the process: production, organization, storage & retrieval, dissemination, and implementation. The concept originates from the 1979 publication Knowledge Application: The Knowledge System in Society by Holzner and Marx. The authors viewed the systems perspective as a way to cope with society’s complex knowledge society. In our modern society we can make sense of organizations and professional roles (and their interconnectedness) by viewing them as systems. For instance, a radio station (on a macro-level) can be viewed as having a type of dissemination role in society’s knowledge system. It disseminates or transmits information as the prime knowledge system function. However, it also can be viewed as having its own Knowledge System: production of reports, organization of music and/or interviews, transfer and implementation procedures for standards in their professional field. In this way, Knowledge Transfer can represent different dimensions: 1) research production 2) dissemination or diffusion 3) implementation of policy 4) evaluation of existing policy. In this way the systems approach can help researchers and policy makers avoid some of the confusion about Knowledge Transfer. That is to say, some issues framed as “Knowledge Transfer” may really concern issues of the production or retrieval of 11 knowledge (whether from databases or from human work practices). Using a systems perspective we can directly focus on which component of the system is most important to the transfer of knowledge. Recently, the systems perspective has been applied in knowledge management. Knowledge management issues, such as discussed by Alavi & Leidner (2001), utilize a systems perspective as an organizing concept that helps contextualize future management research. (For a bibliometric account of knowledge systems thinking, see Graham & Dickinson, 2007). Section 2: Subject Divisions In the last section, we explored issues of Knowledge Transfer by accessing materials through a terminological search, using the language of Knowledge Transfer. It was clear from this searching experiment that different terminology retrieves different results, even though the terms are used almost synonymously. This section approaches Knowledge Transfer from the perspectives specific subject matter, such as health, business and governance. For each subject, recommendations will be given for journals and database that may be of interest. Again, this section approaches the subject from the information scientist perspective with a focus on how to find and organize Knowledge Transfer resources. a. Business and Management As stated previously, business and management play a large part of Knowledge Transfer research and development today. One of the keystones of this process is the assumption that knowledge moves in and moves out of the human mind as data moves in and out of computer storage. The knowledge stored in human experience, routines, and communities in the work place, is a strategic value for business. In large part this has been a result of the use (or misuse) of Polanyi’s (1966) concept of “Tacit Knowledge”. Although this work dates from the late 60s, the concept was popularized by Nonaka within a business framework in the 90s (Nonaka, 1994). His work concerning the codification of personal, tacit knowledge set the groundwork for a flurry of management processes, articles, books and theses. Although the value of this process is mainly contextualized in the form of internal value to the firm, cross-cultural knowledge 12 exchange has become of importance too. Lam (1997) examines the role of embedded knowledge or tacit knowledge within a cross-cultural exchange between Japanese and British technology firms; “societal settings” affect the nature of the transfer effort and expectations. Utilizing the tacit knowledge of individuals is one line of reasoning for effective Knowledge Transfer. The following bulleted list of resources reveals the diversity of Knowledge Transfer literature found in the business and management world: Consulting/Consultancy (Hall, 2006; Svensson, 2007) Organizational Culture (Al-Alawi, Al-Marzooqi & Mohammed, 2007; Miesing, Kriger & Slough, 2007) Organizational Learning (Chau & Pan, 2008) Knowledge Management (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Bolisani & Scarso,1999) University-Business Linkages (Etzkowitz, 2003; Horowitz-Gassol, 2007) Immigration and Industry (Williams, 2007) Interesting Journals: Journal of Technology Transfer, Technovation, Futures, Journal of Knowledge Management, Knowledge Management Research & Practice, The Learning Organization, California Management Review (see V40/ Iss.3), Organization Science, British Journal of Management Databases to Review: ABI full text, Business Index ASAP, Google Scholar, Scopus b. Health and Medicine Health Knowledge Transfer is an ever increasing field of study branching into different areas of technical, clinical and social realms. There are different audiences of health professionals such as policy makers, clinicians and, especially, the patients themselves (who are now becoming empowered via the imperative of evidence based medicine combined with greater access to medical information on the Internet). Resources abound on any one area of health Knowledge Transfer. For example, a significant and important collection of resources exists in the nursing profession alone. A search for nursing Knowledge Transfer and utilization reveals a specific history with context specific models: Stetler Model, Iowa Model, CURN Project (Titler & Goode, 1995). Thus, an important lesson from Knowledge Transfer is that each profession may have a distinct history with professional programs and research models specific to their own professional development. 13 One of the difficulties of such a large literature is the lack of organization in the field, but this is changing. The authors Greenhalgh et al. (2005) systematically organized transfer efforts in Diffusion of Innovation in Health Service Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review. This book stands as the best example for systematically clarifying the methodologies of Knowledge Transfer for health improvement. If such efforts were duplicated for each major subject area (governance, business, etc.) the retrieval and comprehension of Knowledge Transfer for professionals would be improved drastically. The following Knowledge Transfer health articles represent only a fraction of the resources available: Research Use in Nursing (French, 2005a, 2005b; Titler & Goode, 1995) Health policy making (Dobbins & Twiddy, 2004; Kothari, Birch & Charles, 2005) Evidence-based movement (Lemieux-charles, McGuire, & Blidner, 2002) Clinical applications (Loiselle, Semenic & Cote, 2005; Genuis & Genuis, 2006) Building knowledge based health organizations (Wickramasinghe, Gupta, Sharma, 2005) Interesting Journals: Implementation Science, Journal of Advanced Nursing, Worldviews on Evidence-based Nursing, Nursing Research, Science Communication, Databases to Review: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus; see specific vendors such as Sage Journals. c. Governance and Policy Knowledge Transfer (also involving Policy Transfer) is a major component of modern day government, academia and policy organizations. This type of Knowledge Transfer is recognizable in policy implementation monographs, such as Hill and Hupe (2002). Policy implementation typically involves types of knowledge structures (topdown/bottom-up), policy cycles, program evaluation, and examples of communicative strategies for appropriate action to fulfill policy mandates. One of the most valuable sources for research on governance or policy for implementing research is the Policy Press. For instance, the text Using Evidence: How Research can Inform Public Services addresses the different ways research can be used, how to shape research into policy and practice, and outlines the various models of research.4 One of their relatively new 4 See the Policy Press website (https://www.policypress.org.uk/ 14 journals, Evidence & Policy, focuses on the issues of implementing and using research. Some examples in the wider literature include the following: Implementation Units (deLeon, 1999; Lindquist, 2006) Policy Transfer (Evans, 2004) KT in Education Policy (Mitchell, 1998) Technology Transfer and Public Policy (Bozeman, 2000) Interesting Journals: Evidence & Policy, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Policy Studies Review, Public Administration Review. Databases to Review: Academic Search Premier, International Political Science Abstracts (IPSA), Web of Science, Scopus. Section 3: Knowledge Transfer by Role In the last section, different Knowledge Transfer resources were examined via subject access: health, business, governance. These perspectives are from an information science perspective and reveal the different ways that information on Knowledge Transfer can be retrieved. However, this brief report will now focus on some of the professional roles by individuals and organizations. The role of Knowledge Broker is probably the most significant role within the Knowledge Transfer field. This concept was significantly addressed by Havelock (1986); he classified the rudimentary brokering activities: Locator, Implementation Assister, Relay Station, Transformer, Synthesizer. Dunn (1986) interprets the rise of this new social role as a natural response to the identification of gaps in the use of knowledge. The rise of this role again stresses the importance of social interaction as a determinant of knowledge use (Armstrong et al., 2006: 386). A prima facie evaluation of this role reveals two distinct modes of Knowledge Brokering: 1) Individuals who take on the role of brokering knowledge as a third party operator or linker; and 2) Organizations whose mandates focus on brokering as a specific operation. From the professional perspective, one of the more formal documented success stories using this model comes from the health system in Australia. A “community liaison model” was utilized employing two “community liaison officers” (CLOs) (Mitchell & Walsh, 2003: 266). These brokers were hired to facilitate Knowledge Transfer from the very beginning of a health project, before any research had 15 begun. The CLOs were able to identify the best strategies for transferring knowledge to a specific community; for example, they identified the need for assessing literacy levels in the transfer of health knowledge to the public. The results showed a successful Knowledge Transfer strategy for communicating health information to a community. Another form of brokering is based on an academic model. Academic projects usually involve comprehensive literature reviews that reveal key players in different subject areas. For example, in a project involving a search for resources in Canadian aboriginal law the author of this report engaged in academic Knowledge Brokering based on the formation of a bibliography. A basic web search revealed a comprehensive bibliography on Canadian Aboriginal law. The authors of the bibliography had been hired by the federal government in Ottawa, Ontario to compile a comprehensive bibliography on Aboriginal rights and laws. Given that a federal government agency in Ottawa and scholars here at the University of Saskatchewan were both investigating the same topic, it seemed intuitively correct to contact the federal agency and attempt to broker a relationship. An introductory email (and later, a conference call) led to the collaboration of a federal government manager and an academic researcher here at the University of Saskatchewan. Nevertheless, the CLO model and the academic model is the exception, not the rule. Most employment positions do not stress (or reward) brokering activity. The other important brokering role occurs on an organizational level. One of the major health research funders in Canada, the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) has produced many documents on the requirements of brokering, maintaining that the key component is “bringing people together” (CHSRF, 2003). Also in Canada, “Research Impact” is an organization that not only discusses the role of brokering but acts as a community-government-academic broker enlisting many diverse professionals (Research Impact, 2007). In Britain, the Scottish Executive has also produced reports on the role of Knowledge Brokering emphasizing the following needs: dedicated resources to support implementation; management education and skills development; identifying collaborative networks; as well as a ‘knowledge exchange’ facility to organize and disseminate knowledge (Clark, 2005). The search for Knowledge Broker/ing suffers from the same difficulties as Knowledge Transfer. Knowledge Brokering may be known by different names: Knowledge 16 Champions, Liaison Officers, Linkers, Synthesizers, Boundary Spanners, etc. This means that brokering roles are not always easy to discover in the formal literature. One special strategy for finding such resources involves a rethinking of basic search strategies. In addition to searching the terms themselves—brokers, linkers, etc.—it also is helpful to search for environments wherein brokers may be working. For example, a search for interdisciplinary research, involving the use intermediaries between the different professionals is fertile ground for discovering brokering roles. When in doubt, search the field, not the subject. Section 4: KT by Models and Theory This history of Knowledge Transfer has also involved attempts to group, classify and clarify the activities of its professionals. Although each Knowledge Transfer project or process can vary greatly, this section addresses Knowledge Transfer by the use of models and theory providing a basic review of the more popular concepts. a. Models The bet noir of Knowledge Transfer and utilization has been the absence of a successful model, accepted as valid by transfer professionals. “No one conceptual model has yet gained unanimous approval among knowledge utilization experts” (Belkhodja et al., 2007: 378). However, Knowledge Transfer is dominated by four reoccurring themes from the last 3 decades of growth in the literature: Instrumental, Conceptual, Symbolic and Interactive. Although there are many others, these approaches remain popular models of understanding and clarification in the literature. Instrumental: This model of Knowledge Transfer represents a decision making model, one that can be made rationally, based on the best evidence or research. “For example, instrumental utilization of research can be said to have taken place when there is evidence of policy makers and practitioners acting on the findings of specific research studies” (Alcock 2004: 19). This model of decision making reflects a rational approach. It assumes that people engage in a set of rational activities, weigh all alternatives, and carefully scrutinize available evidence (Hasenfeld & Patti, 1992). 17 Conceptual: Sometimes referred to as educational or enlightenment model, this particular emphasis on Knowledge Transfer and utilization proposes that knowledge or research mainly informs people about a particular position. The conceptual use of information occurs when reading research that contextualizes a situation. Weiss (1980) described such a process as “Knowledge Creep”. This occurs also in the sense of professional development, or to “keep up with the field” (387). Research is used more often for general guidance in this model. Symbolic: The symbolic use of knowledge consists in using research in ways that supports pre-established positions or preferences. Decision makers may wish to use research symbolically to support programmes associated with political ideologies (Amara, Ouimet & Landry, 2004). This position can be associated with “bargainingconflict model” and the “Political Model” of decision making (IBID, 78). Although mainly associated with undesirable motivations, the symbolic use of research might also be used in a positive manner, such as seeking empowerment. For example, symbolic use of research may champion the establishment of a task force or research team to provide further evidence for what may only be known anecdotally. The symbolic use of knowledge can occur post-implementation: the use of research to support a position might be used by governments to bolster public support for legislation that has been recently enacted or under review. Interactive Model: Of special importance today is the championing of interactive models that foster the sharing of Knowledge Transfer and utilization based on the collaboration of different stakeholders (users and producers) and how they interact with each other (Kothari, Birch, and Charles, 2005). Sometimes referred to as a participatory approach, Weiss (1991) championed practitioners (those who apply knowledge) collaborating with the researchers (those who produce knowledge) for effective transfer. Another example: Reed & Simon-Brown (2006) identify three major players in the transfer and application of forestry knowledge: researchers, Knowledge Transfer professionals, and practitioners. This is fast becoming the most important of the different 18 models, mainly due to the efforts for joint decision making and increasing public appetite for citizen involvement in policy making. Most evident today in public policy decision making has been the attempts at many levels to include the public as a vital component of the decision making process. Although not always identified in the Knowledge Transfer literature, it is believed advantageous for implementation of policies and practices to involve citizen participation. Different approaches may include: Planning Cells (Hendriks, 2006) Citizens’ Juries (Iredale & Longley, 2007) Multilateral communication (Walter & Scholz, 2007) Integrated Assessment (Ravetz, 1999) Other Models Researchers have identified many different models in research practice, sometimes overlapping with the three previously mentioned models above. Science Push Model, Dissemination Model (Belkhoda et al., 2007) Linear Model, Translation Model (Lawrence, 2006) Ottawa Model for Research Use (Logan and Graham, 1998) b. Theory Considerations on the application of knowledge depend to some extent upon existing or changing knowledge structures in society. The transfer of knowledge in a centralized system is different than a decentralized system, whether in health or business. In recent years, some theories have attempted to describe the structures of Knowledge Transfer in society. Although not exhaustive, some of these are the Post-Academic Science, Agora, Mandated Science, Knowledge Society, Knowledge Based Economy, but most popularly, the theories of Mode 2 Knowledge Production, the Triple Helix and Post Normal Science stand out as important concepts to consider when thinking of knowledge transfer in society (see Graham & Dickinson, 2007 for a bibliometric analysis of all three theoretical approaches). Mode 2 Knowledge Production: The production and transfer of knowledge has an interdisciplinary structure (Gibbons et al 1994). Knowledge is produced from many different sites with dispersed responsibility. 19 Triple Helix: Mainly championed by Henry Etzkowitz (2003), the Triple Helix explains the new relationship between Industry-Government-Academia. The transfer of knowledge occurs institutionally. Post Normal Science (PNS): Somewhat different from Mode 2 and the Triple Helix, PNS is a new approach for understanding science in the policy process; it extends our sources of knowledge, especially in situations that call for distributive decision making. In situations of low clarity it may be necessary to utilize an “extended peer community” of professionals, so as to extend the decision making and responsibility for decision making (See Futures volume 31, issue 7 for a special issue on Post Normal Science). Section 5: Empirical Studies The need for clarification and organization of empirical studies in Knowledge Transfer is paramount. Each area of Knowledge Transfer may diverge into different paths, with different tools and processes (as stated before, a brief investigation into nursing knowledge utilization literature reveals a very distinct set of tools and programmes). Empirical research can be divided into two distinct categories: 1) standard research methods or processes used to evaluate Knowledge Transfer; and 2) special tools devised specifically with Knowledge Transfer as their focus. Some standard research tools in the field are as follows: content analysis, bibliometrics, factor analysis, regression analysis, inferential statistics and social network analysis; more recently, environmental scanning, logic models and case studies have become popular. Early in the 1980s, Dunn (1983a,b; Dunn, Dukes & Cahill 1984) accounted for some of the special research tools: Information Utilization Scale, Stage of Concern Scale, Levels of Use Scale, An Evaluation Scale, Research Utilization Index and Overall Policy Impact Scale. In nursing, special tools for research utilization and transfer of knowledge include, but are not limited to the following: PARHIS, Iowa Model of Research in Practice, Stetler Model, BARRIERS to Research Utilization Scale, Research Factor Questionnaire. Many empirical studies exist, so only a few can be outlined here; however, there are representative papers that can reveal the complexity of composing and implementing a Knowledge Transfer study. Amara, Mathieu and Landry (2004) address the analysis of instrumental, conceptual and symbolic uses of knowledge. Not only did the authors survey 833 government officials organizing the results via these traditional models, but 20 they provided a summary of empirical studies that had done likewise. According to their work, there are few rigorous empirical studies that address Knowledge Transfer; the concern for more rigorous and methodologically substantive research is an ongoing concern in this field. Their research found that government agencies engaged in a use of all three models of Knowledge Transfer. Likewise, Landry et al. (2001) evaluated Knowledge Transfer from different knowledge stages using Knott-Wildasky’s Scale of Knowledge Utilization. Propper (1993) attempts to measure the reasoning skills of those involved in scientific and political discussions (using Habermas’s Communicative rationality and communicative acting as a conceptual focus). Belkhodja et al. (2007) address the different components of organizational determinants for Knowledge Transfer. Yet, even with all the current empirical studies that exist, the creation of Knowledge Transfer theory and measures that definitively show knowledge impact and transfer remains a continuous goal. Section 6: Resources and Tools Briefly, this guide will provide some awareness of the development of resources and tools in the understanding and clarification of Knowledge Transfer. This will involve accounting for some interesting online resources and some basic communicative tools. a. Online Resources There is now a growing response to the need to provide clarity for Knowledge Transfer. Of course, the Internet plays a vital role in organizing these efforts. Providing a tool for conceptual clarity, the Research Transfer Network of Alberta (RTNA) has implemented the use of a Wikipedia style website in an attempt to harness the variety of perspectives in the area of Knowledge Transfer.5 Their Wiki includes sections on defining Knowledge Transfer and investigating the origins of the field. This is a novel idea that every organization might consider as it sets an agenda for the future. One of the more comprehensive resources on the web is the Knowledge Utilization online database from Laval, Quebec, Canada. Rejean Landry, Chair on Knowledge Transfer, provides an online database of resources, including: articles, reports, books, 5 http://www.ahfmr.ab.ca/rtna/wiki/index.php/Main_Page 21 links, etc. Although Landry’s focus is primarily health policy, many of the resources can be applied general to transfer knowledge: statistics, social sciences, bench marking, etc. (See http://kuuc.chair.ulaval.ca/english/master.php?url=recherche.php) (For a faceted analysis approach to retrieving Knowledge Transfer resources, see the Knowledge Utilization and Policy Implementation (KUPI) database created by the author of this report: http://publications.usask.ca/kupi/index.php ). Although not directly placed in the context of Knowledge Transfer, podcasting is also becoming an avenue for online knowledge dissemination and learning. An innovative knowledge strategy was implemented by Mississippi State University by using podcasts to promote the use of government documents collections (Barnes, 2007). This strategy can certainly be extended into the realm of Knowledge Transfer for all the major professions. Another innovative example of digital Knowledge Transfer includes the use of social networking software, such as Facebook. Sometimes these websites are blocked by management structures that view them as too much like socializing and less like working. However, access to social networking software sites can be incredibly instructive and helpful for the Knowledge Transfer process. For example, besides the onslaught of personal sites and applications, Facebook allows for professional groups to co-locate their intellectual space. In the UK, Facebook is used for just this purpose by the “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTP)” group: “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTP) is a UKwide scheme to improve UK competitiveness and productivity by facilitating collaboration between universities and companies” (Lam, 2007). Although still in need of professional development and leadership facilitating, such sites can add a degree of informal tacit knowledge exchange, and a sense of professional belonging. Furthermore, academically speaking, an inexpensive way to enlist participants in studies and share personal experiences will no doubt make use of Facebook as its popularity increases and its usefulness as a research ground becomes more acceptable. b. Tools Knowledge Transfer tools consist of two distinct categories: 1) research methods that have been adapted to the needs of transfer and implementation; and 2) special transfer mechanisms (as is the case for empirical studies; indeed, they overlap). For example, a 22 modern research tool growing in importance and value are systematic reviews for decision making (Lavis et al., 2005). The systematic review, most popular in health and clinical practice, is fast becoming the pivotal tool of policy practitioners and clinicians for social and health intervention. This can be noticed in a new methodological perspective that expands on systematic reviews, called an “Argument Catalogue” (Abrami, Bernard, and Wade, 2006). The Argument Catalogue is constructed using systematic review methods for the purpose of compiling various types of evidence for a specific rationale; for example, to provide evidence for a specific health rationing decision an argument catalogue might involve collecting a diverse set of resources: newspapers, notes from town hall meetings, and technical reports. However, it provides more value from research sources by involving a coding scheme for presenting selections of data pertinent to different stakeholders. (Below is a summary from Abrami, Bernard, & Wade, 2006: 419-20). Argument Catalogues can… Function to identify the consistencies and inconsistencies that exist between research evidence, public policy, practitioner experience and public perception Develop a comprehensive understanding of the issues, including impacts, applications, and the factors that moderate effectiveness and efficiency. Frame the questions to be addressed in a more scholarly review, such as a metaanalysis, and in suggesting important study features that may be subsequently coded and analyzed. Supplement analysis and aid in the understanding the findings of a meta-analysis. Provide a way for policy makers and practitioners to understand that their expertise and views are represented. More specific tools, such as planning guides to Knowledge Transfer are also becoming popular, such as Lavis’s (2006) research planning guide for transfer. Lavis devised five key questions to evaluate in knowledge transfer: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. What is the message? Who is the audience? From what source or messenger? What method is being used for transfer of knowledge? With what expected impact evaluation? Start & Hovland (2004) amassed a core set of policy tools for transferring knowledge. These were divided into 4 major groups: communication tools, context assessment tools, policy influence tools and research tools. Their main approach is the “context, evidence, 23 links” framework. A basic search for “Policy” and “Knowledge Transfer” will reveal a host of organizations that provide such tools. Finally, information technology, depending on the project, can empower those doing Knowledge Transfer. These include personal digital assistants/blackberries, teleconferences, telehealth, and documents available online (SHRF, 2007). Conclusion This brief report has provided a basic guide to the conceptual and practical issues of Knowledge Transfer, specifically, the challenges of retrieving, organizing and understanding this diverse subject. Knowledge Transfer is a challenging field to investigate because of the diverse use of language, the multipurpose goals and activities, as well as the array of models, studies, tools and online resources. In concluding, the report will end with a number of basic reminders and recommendations for all those interested researchers and policy makers involved in Knowledge Transfer activities: Reminders 1) Consider your terminology: The terminology you use for investigating a subject can steer your search in various directions. A search for “Knowledge Transfer” retrieves different results than “Knowledge Translation” even though they are based on similar, expected outcomes. Before engaging in any major “Knowledge Transfer” project, be mindful of the different terminology. This may mean traversing a complex semantic environment wherein your organization uses the term “Knowledge Translation” to describe its activities, but your most valuable documents are found in the “Knowledge Utilization” literature. 2) Consider your subject: It is okay to limit a study of Knowledge Transfer to a specific subject—business and governance, for example—so long as you know that other subject areas, such as nursing, may have different approaches to the Knowledge Transfer that may be commensurable with your area of study. Another example: searching only business resources for empirical studies may be too limiting if you want a full and comprehensive approach to Knowledge Transfer. 24 Recommendations 1) Consider establishing a Knowledge Transfer Unit: Whether you work in an organization, or on an academic campus, the benefits of a Knowledge Transfer Unit are evident. The organization of professionals, goals and resources to assist an organization or an academic department seems obvious; the professionals can focus on producing the best research possible, and Knowledge Transfer professionals (brokers, liaisons, etc.) can focus on application and implementation. Although not exactly parallel in structure and goals, the use of “Implementation Units” by British and Australian governments stands as a good formal example of strategic, planned transfer and implementation activity (Lindquist, 2006). 2) Consider the Systems Approach: The use of the term “Knowledge Transfer” is many times too broad to be meaningful, unless specifically defined and limited. One way to clarify your Knowledge Transfer goals is by taking a systems approach (as described earlier in this report, inspired by Holzner & Marx, 1979). When approaching any Knowledge Transfer project, investigate first the different aspects of the system, and determine which component is most important: production, management (organization & retrieval), dissemination (transfer), application, and implementation. In this way, you not only define the area of most importance but you can make connections in your organization or department, seeing the different system links. One way of going about this is to use various visual tools: concept maps, logic models, social network analysis, and systems analysis. Some areas will no doubt be overlapping, but this would also be mapped in your systems perspective (see Graham & Dickinson, 2007 for an example of using a systems perspective). 25 Acknowledgements: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the Knowledge Utilization and Policy Implementation project (2002-2007). Dr. Carole Estabrooks is the Principal Investigator and the Co-investigators are Dr. Rejean Landry, Dr. Harley Dickinson and Dr. Karen Golden-Biddle. The contents of this report were made possible by such funding and the continued support for such work at the Social Research Unit, Sociology Department, University of Saskatchewan. Paul J Graham served as the Research Librarian for the project starting in the summer, 2003. Special thanks to Dr. Liz Quinlan for her advice and assistance in the formation of this basic guide. References Cited Abrami, P. C., R. M. Bernard, and C. A. Wade. "Affecting Policy and Practice: Issues Involved in Developing an Argument Catalogue." Evidence & Policy 2, no. 4 (2006): 417-37. Al-Alawi, Adel Ismail, Nayla Yousif Al-Marzooqi, and Yasmeen Fraidoon Mohammed. "Organizational Culture and Knowledge Sharing: Critical Success Factors." Journal of Knowledge Management 11, no. 2 (2007): 22-42. Alavi, Maryam, and Dorothy E. Leidner. "Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues." MIS Quarterly 25, no. 1 (2001): 107-36. Alcock, Pete. "Social Policy and Professional Practice." In Understanding Research for Social Policy and Practice, edited by Saul Becker and Alan Bryman. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2004. Amara, Nabil, Mathieu Ouimet, and Rejean Landry. "New Evidence on Instrumental, Conceptual, and Symbolic Utilization of University Research in Government Agencies." Science Communication 26, no. 1 (2004): 75-106. Argote, L., P. Ingram, J. M. Levine, and R. L. Moreland. "Knowledge Transfer in Organizations: Learning from the Experience of Others." Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 82, no. 1 (2000): 1-8. Armstrong, R., E. Waters, H. Roberts, S. Oliver, and J. Popay. "The Role and Theoretical Evolution of Knowledge Translation and Exchange in Public Health." Journal of Public Health 28, no. 4 (2006): 384. Barnes, N. "Using Podcasts to Promote Government Document Collections." Library Hi Tech 25, no. 2 (2007): 220-30. 26 Beal, George M. "Knowledge Generation, Organization Dissemination and Utilization for Rural Development." In 5th World Congress for Rural Sociology. Mexico City: US Department of Health, Education & Welfare. National Institute of Education., 1980. Beal, George M., and Peter Meehan. "Communication in Knowledge Production, Dissemination, and Utilization." In Knowledge Generation, Exchange and Utilization, edited by George M. Beal, Wimal Dissanayake and Sumiye Konoshima, 11-34. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1986. Belkhodja, O., N. Amara, R. Landry, and M. Ouimet. "The Extent and Organizational Determinants of Research Utilization in Canadian Health Services Organizations." Science Communication 28, no. 3 (2007): 377. Beyer, J. M. "Research Utilization: Bridging a Cultural Gap between Communities." Journal of Management Inquiry 6, no. 1 (1997): 17-22. Birkinshaw, Julian, Robert Nobel, and Jonas Ridderstrale. "Knowledge as a Contingency Variable: Do the Characteristics of Knowledge Predict Organization Structure?" Organization Science 13, no. 3 (2002): 274-89. Bock, Gee-Woo, Robert W. Zmud, Young-Gul Kim, and Jae-Nam Lee. "Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social-Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate." MIS Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2005): 87-111. Bolisani, Ettore, and Enrico Scarso. "Information Technology Management: A Knowledge-Based Perspective." Technovation 19, no. 4 (1999): 209-17. Bose, Ranjit. "Knowledge Management Metrics." Industrial Management & Data Systems 104, no. 6 (2004): 457-68. Bozeman, Barry. "Technology Transfer and Public Policy: A Review of Research and Theory." Research Policy 29, no. 4/5 (2000): 627-55. Burgess, D. "What Motivates Employees to Transfer Knowledge Outside Their Work Unit?" Journal of Business Communication 42, no. 4 (2005): 324. Carlile, Paul R. "A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries: Boundary Objects in New Product Development." Organization Science 13, no. 4 (2002): 442-55. Chiang, Yung-chen. Social Engineering and the Social Sciences in China 1919-1949. London: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Choi, Bernard C.K., and Anita W.P. Pak. "Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in Health Research, Services, Education and Policy: 1. 27 Definitions, Objectives, and Evidence of Effectiveness." Clinical and Investigative Medicine 29, no. 6 (2006): 351-64. Chou, Shih-Wei, and Mong-Young He. "Knowledge Management: The Distinctive Roles of Knowledge Assets in Facilitating Knowledge Creation." Journal of Information Science 30, no. 2 (2004): 146-64. CHSRF. "The Theory and Practice of Knowledge Brokering in Canada's Health System." 16. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2003. Chua, Ai Ling, and Shan L. Pan. "Knowledge Transfer and Organizational Learning in Is Offshore Sourcing." Omega 36, no. 2 (2008): 267-81. CIHR. "About Knowledge Translation." Canadian Institutes for Health Research, http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html. Clark, Gill, and Liz Kelly. "New Directions for Knowledge Transfer and Knowledge Brokerage in Scotland." Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Social Research, 2005. Crewe, Emma, and John Young. "Bridging Research and Policy: Context, Evidence and Links." vii, 33. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2002. deLeon, P. "The Missing Link Revisited: Contemporary Implementation Research." Policy Studies Review 16, no. 3/4 (1999): 311-38. Dobbins, M., and T. Twiddy. "A Knowledge Transfer Strategy for Public Health Decision Makers." Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 1, no. 2 (2004): 12028. Duguid, Paul. ""The Art of Knowing": Social and Tacit Dimensions of Knowledge and the Limits of the Community of Practice." The Information Society 21, no. 2 (2005): 109-18. Dunn, William. "Measuring Knowledge Use." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 5, no. 1 (1983a): 120-33. ———. "Qualitative Methodology." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 4, no. 4 (1983b): 590-97. ———. "Studying Knowledge Use: A Profile of Procedures and Issues." In Knowledge Generation, Exchange and Utilization, edited by George M. Beal, Wimal Dissanayake and Sumiye Konoshima, 369-403. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1986. Dunn, William, Mary J Dukes, and Anthony G Cahill. "Designing Utilization Research." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 5, no. 3 (1984): 387-404. 28 Etzkowitz, H. "Innovation in Innovation: The Triple Helix of University-IndustryGovernment Relations." Social Science Information Sur Les Sciences Sociales 42, no. 3 (2003): 293-337. French, Beverley. "The Process of Research Use in Nursing " Journal of Advanced Nursing 49, no. 2 (2005a): 125-34. ———. "Evaluating Research for Use in Practice: What Criteria Do Specialist Nurses Use?" Journal of Advanced Nursing 50, no. 3 (2005b): 235-43. Garud, Raghu, and Arun Kumaraswamy. "Vicious and Virtuous Circles in the Management of Knowledge: The Case of Infosys Technologies." MIS Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2005): 9-33. Genuis, Shelagh K., and Stephen J. Genuis. "Exploring the Continuum: Medical Information to Effective Clinical Practice. Paper I: The Translation of Knowledge into Clinical Practice." Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 12, no. 1 (2006): 49-62. Gibbons, M, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott, and Martin Trow. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. New York: Sage Publications, 1994. Graham, Paul J. and Harley Dickinson. “Knowledge-System Theory in Society: Charting the Growth of Knowledge-System Models over a decade, 1994-2003.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58, no. 14 (2007): 2372-2381. Grantham, C.E. "Technology Transfer: The Organizational Role." ACM SIGCHI Bulletin 17, no. 2 (1985): 25-28. Greenhalgh, Trisha , Glenn Robert, Paul Bate, Fraser Macfarlane, and Olivia Kyriakidou. Diffusion of Innovations in Health Service Organisations : A Systematic Literature Review. Published Malden, Mass BMJ Books/Blackwell Publisher, 2005. Guetzkow, Harold. "Conversion Barriers in Using Social Sciences." Administrative Science Quarterly 4, no. 1 (1959): 68-81. Hall, Matthew "Knowledge Management and the Limits of Knowledge Codification." Journal of Knowledge Management 10, no. 3 (2006): 117-126. Hansen, Morten T., Nitin Nohria, and Thomas Tierney. "What's Your Strategy for Managing Knowledge?" Harvard Business Review (1999). 29 Hasenfeld, Yeheskel, and Rino Patti. "The Utilization of Research in Administrative Practice." edited by Anthony J. Grasso and Irwin Epstein, 221-39. New York: Hawworth Press, 1992. Havelock, Ronald G. "Linkage: Key to Understanding the Knowledge System." In Knowledge Generation, Exchange and Utilization, edited by George M Beal, Wimal Dissanayake and Sumiye Konoshima, 211-43. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1986. Hendriks, C. M. "When the Forum Meets Interest Politics: Strategic Uses of Public Deliberation." Politics & Society 34, no. 4 (2006): 571. Hill, Michael, and Peter Hupe. Implementing Public Policy: Governance in Theory and in Practice, Sage Politics Texts. London: Sage Publications, 2002. Holzner, Burkart, and John H. Marx. Knowledge Application: The Knowledge System in Society. Boston, Mass.: Allyn and Bacon, 1979. Horowitz-Gassol, Jeaninne. "The Effect of University Culture and Stakeholders’ Perceptions on University–Business Linking Activities." The Journal of Technology Transfer 32, no. 5 (2007): 489-507. Research Impact. "About Us.” Research Impact, http://www.researchimpact.ca/ about/index.html Inkpen, A. C., and W. Pien. "An Examination of Collaboration and Knowledge Transfer: Chinasingapore Suzhou Industrial Park." Journal of Management Studies 43, no. 4 (2006): 779-811. Iredale, Rachel, and Marcus Longley. "From Passive Subject to Active Agent: The Potential of Citizens' Juries for Nursing Research." Nurse Education Today 27, no. 7 (2007): 788-95. Iverson, Joel O, and Robert D McPhee. "Knowledge Management in Communities of Practice." Management Communication Quarterly : McQ 16, no. 2 (2002): 259. Knorr-Centina, K. Epistemic Cultures: How Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. Knott, Jack H, and Aaron Wildavsky. "If Disemination Is the Solution, What Is the Problem?" Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 1, no. 4 (1980): 537-78. Kothari, Anita, Stephen Birch, and Cathy Charles. ""Interaction" And Research Utilisation in Health Policies and Programs: Does It Work?" Health Policy 71, no. 1 (2005): 117-25. 30 Kramer, D. M., and R. P. Wells. "Achieving Buy-In: Building Networks to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer." Science Communication 26, no. 4 (2005): 428-44. Lam, Alice. "Embedded Firms, Embedded Knowledge: Problems of Collaboration and Knowledge Transfer in Global Cooperative Ventures." Organization Studies 18, no. 6 (1997): 973-96. Lam, Si Chun "Information." Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTP), http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=2205083757 Landry, Rejean, Nabil Amara, and Moktar Lamari. "Utilization of Social Science Research Knowledge in Canada." Research Policy 30, no. 2 (2001): 333-49. Landry, Rejean, Moktar Lamari, and Nabil Amara. "The Extent and Determinants of the Utilization of University Research in Government Agencies." Public Administration Review 63, no. 2 (2003): 192-205. Lavis, John. "From Research to Practice: A Knowledge Transfer Planning Guide." 10: Institute of Work & Health, 2006. Lavis, J., H. Davies, A. Oxman, J. L. Denis, K. Golden-Biddle, and E. Ferlie. "Towards Systematic Reviews That Inform Health Care Management and Policy-Making." Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10, no. Suppl. 1 (2005): S1:35S1:48. Lawrence, Ruth. "Research Dissemination: Actively Bringing the Research and Policy Worlds Together." Evidence & Policy 2, no. 3 (2006): 373-84. Lemieux-Charles, Louise, Wendy McGuire, and Ilsa Blidner. "Building Interorganizational Knowledge for Evidence-Based Health System Change." Health Care Management Review 27, no. 3 (2002): 48-59. Lindquist, E. "Organizing for Policy Implementation: The Emergence and Role of Implementation Units in Policy Design and Oversight." Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 8, no. 4 (2006): 311-24. Logan, J. O., and Ian D. Graham. "Toward a Comprehensive Interdisciplinary Model of Health Care Research Use." Science Communication 20, no. 2 (1998): 227-46. Loiselle, C. G., S. Semenic, and B. Cote. "Sharing Empirical Knowledge to Improve Breastfeeding Promotion and Support: Description of a Research Dissemination Project." Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2, no. 1 (2005): 25-32. Machlup, Fritz. "Uses, Value, and Benefits of Knowledge." Knowledge: Creation Diffusion Utilization 1, no. 1 (1979): 62-81. 31 Matusik, Sharon F., and Michael B. Heeley. "Absorptive Capacity in the Software Industry: Identifying Dimensions That Affect Knowledge and Knowledge Creation Activities." Journal of Management 31, no. 4 (2005): 549-72. Miesing, Paul, Mark Kriger, and Neil Slough. "Towards a Model of Effective Knowledge Transfer within Transnationals: The Case of Chinese Foreign Invested Enterprises." The Journal of Technology Transfer 32, no. 1 (2007): 109-22. Mitchell, Anne, and Jenny Walsh. "The Community Model of Research Transfer." In Evidence-Based Health Policy, edited by Vivian Lin and Brenda Gibson, 263-71. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2003. Munier, Franics, and Patrick Ronde. "The Role of Knowledge Codification in the Emergence of Consensus under Uncertainty: Empirical Analysis and Policy Implications." Research Policy 30, no. 9 (2001): 1537-51. Nelkin, Dorothy. "Knowledge Utilization as Planned Social Change." Knowledge: Creation Diffusion Utilization 1, no. 1 (1979): 106-22. Nonaka, Ikujiro. "A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation." Organization Science 5, no. 1 (1994): 469-70. Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Noboru Konno. "The Concept Of "Ba": Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation." California Management Review 40, no. 3 (1998): 40-54. Nonaka, Ikujiro , and Hirotaka Takeuchi. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Ortenblad, Anders. "A Typology of the Idea of Learning Organization." Management Learning 33, no. 2 (2002): 213-30. Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Garden City: Doubleday, 1966. Propper, Igno M. A. M. "Sound Arguments and Power in Evaluation Research and Policy-Making: A Measuring Instrument and Its Application." Knowledge: Creation Diffusion Utilization 15, no. 1 (1993): 78-105. Ravetz, J. "Citizen Participation for Integrated Assessment: New Pathways in Complex Systems." International Journal of Environment and Pollution 11, no. 3 (1999): 331-50. Reed, A. S., and V. Simon-Brown. "Fundamentals of Knowledge Transfer and Extension." In Forest Landscape Ecology: Transferring Knowledge to Practice, edited by Ajith H. Perera, Lisa Buse and Thomas Crow, 181-204. New York: Springer, 2006. 32 Rich, Robert F. “Editor’s Introduction.” Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 1, no. 1 (1979): 3-5. Scarbrough, Harry, and Jacky Swan. "Discourses of Knowledge Management and the Learning Organization: Their Production and Consumption." In The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, edited by Mark Easterby-Smith and Marjorie A Lyles, 495-512. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. Schroeder, Andreas, and David Pauleen. "Km Governance: Investigating the Case of a Knowledge Intensive Research Organisation " Journal of Enterprise Information Management 20, no. 4 (2007): 414-31. SHRF. "Health Research in Action: A Framework for Building Capacity to Share and Use Health Research." 22. Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, 2007. Start, Daniel, and Ingie Hovland. "Tools for Policy Impact: A Handbook for Researchers." 64. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2004. Styhre, Alexander. "Knowledge Management Beyond Codification: Knowing as Practice/Concept." Journal of Knowledge Management 7, no. 5 (2003): 32-40. Svensson, Roger. "Knowledge Transfer to Emerging Markets Via Consulting Projects." The Journal of Technology Transfer 32, no. 5 (2007): 545-59. Szulanski, Gabriel. "The Process of Knowledge Transfer: A Diachronic Analysis of Stickiness." Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 82, no. 1 (2000): 9-27. ———. Sticky Knowledge: Barriers to Knowing in the Firm, Strategy Series. London: Sage Publications, 2003. Szulanski, Gabriel, and Rossella Cappetta. "Stickiness: Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Predicting Difficulties in the Transfer of Knowledge within Organizations." In Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, edited by Mark Easterby-Smith and Marjorie A Lyles, 514-34. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. Szulanski, Gabriel, and Robert J Jensen. "Overcoming Stickiness: An Empirical Investigation of the Role of the Template in the Replication of Organizational Routines." Managerial and Decision Economics 25, no.? (2004): 347-63. Thompson, G. N., C. A. Estabrooks, and L. F. Degner. "Clarifying the Concepts in Knowledge Transfer: A Literature Review." Journal of Advanced Nursing 53, no. 6 (2006): 691–701. 33 Titler, Marita G., and Colleen J. Goode, eds. Research Utilization. Vol. 30(3), The Nursing Clinics of North America. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1995. Tomba, Luigi. "Creating an Urban Middle Class: Social Engineering in Beijing." China Journal 51 (2004): 1-26. Van Den Bosch, Frans A. J. "Absorptive Capacity: Antecedents, Models, and Outcomes." In The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, edited by Mark Easterby-Smith and Marjorie A Lyles, 278-301. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. Walter, A. I., and R. W. Scholz. "Critical Success Conditions of Collaborative Methods: A Comparative Evaluation of Transport Planning Projects." Transportation 34, no. 2 (2007): 195-212. Weiss, Carol H. "Knowledge Creep and Decision Accretion." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 1, no. 3 (1980): 381-404. ———. "Reflections on 19th-Century Experience with Knowledge Diffusion: The Sixth Annual Howard Davis Memorial Lecture, April 11, 1991." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 13, no. 1 (1991): 5-16. Wickramasinghe, Nilmini , Jatinder N D Gupta, and Sushil K Sharma, eds. Creating Knowledge-Based Healthcare Organizations Hershey PA: Idea Group Pub, 2005. Williams, A. M. "International Labour Migration and Tacit Knowledge Transactions: A Multi-Level Perspective." Global Networks 7, no. 1 (2007): 29-50. Wu, W. L., B. F. Hsu, and R. S. Yeh. "Fostering the Determinants of Knowledge Transfer: A Team-Level Analysis." Journal of Information Science 33, no. 3 (2007): 326. Yin, Robert K, and Margaret K Gwaltney. "Design Issues in Qualitative Research: The Case of Knowledge Utilization Studies." 87. Washington, DC: Abt Associates, 1982. ———. "Knowledge Utilization as a Networking Process." Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 2, no. 4 (1981): 555-80. Zaltman, Gerald. "Knowledge Utilization as Planned Social Change." Knowledge: Creation Diffusion Utilization 1, no. 1 (1979): 82-105. 34