Ending the Performance Enhancing Drug Epidemic:

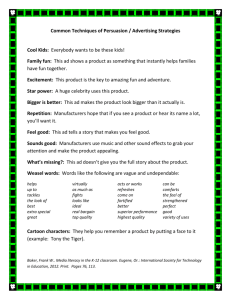

advertisement

#13 Ending the Performance Enhancing Drug Epidemic: Let’s Stop the Problem Where It Starts ~ Imposing Liability on Drug Manufacturers I. Introduction "I started taking anabolic steroids in 1969 and never stopped. It was addicting, mentally addicting. Now I'm sick, and I'm scared. Ninety per cent of the athletes I know are on the stuff. We're not born to be 300lbs or jump 30ft. But all the time I was taking steroids, I knew they were making me play better. I became very violent on the field and off it. I did things only crazy people do. Once a guy sideswiped my car and I beat the hell out of him. Now look at me. My hair's gone, I wobble when I walk and have to hold on to someone for support, and I have trouble remembering things. My last wish? That no one else ever dies this way."1 -Lyle Alzado, former NFL Lineman, during his pain racked final days. Alzado died of brain cancer attributable to excessive hGH and anabolic steroid use.2 Unfortunately, Lyle Alzado is not alone. Performance enhancing drug use has hit epidemic levels3 in today’s society. From high school athletes to professionals, death resulting from such use is all too common. Sport is touted as a “bridge between cultures,” a “celebration of humanity.”4 It brings individuals together, acting as a universally spoken language. The competitive nature that is the very spirit of athletics provokes a desire in athletes to continually strive to enhance their performance.5 Sports today are plagued by the reality6 that the desire for superior performance inspires athletes to use and sometimes abuse legal drugs for performance enhancing purposes.7 “Drug use has a ‘snowball effect’ on athletes.”8 Use of performance enhancing drugs renders an unbalanced competition, which in turn encourages those that are drug-free to become users 1 Memorial to Lyle Alzado, available at http://www.geocities.com/bigcory94533/alzado.html (last visited October 18, 2005). 2 Steroid Substitutes, No. FDA 93-1207 (July 1993), available at http://www.openseason.com/annex/library/cic/X0081_ster_sub.txt.html (last visited October 18, 2005). 3 Steroids and Kids, (December 20, 2004), available at http://sev.prnewswire.com/publishing-informationservices/20041212/NYSU01012122004-1.html (last visited February 27, 2006). 4 Australian Sports Drug Agency: Anti-Doping Forum, (December 2004), available at http://www.asda.org.au/_docs/Adforum_Sydney_Dec04.pdf (last viewed October 18, 2005). 5 The EPO Epidemic in Sport, available at http://www.bloodline.net/stories/storyReader$3144 (last visited March 3, 2006). 6 Who will win the drugs race?: Catching drug cheats is essential if sports are to be conducted on a level playing field – and if deleterious health effects are to be avoided, available at www.science.org.au/nova/055/055key.htm (last visited February 20, 2006). 7 The EPO Epidemic in Sport, supra note 5. 8 Id. 2 themselves, in an effort to remain competitive.9 For example, studies have shown that use of Erythropoietin, a peptide hormone,10 can potentially enhance aerobic capacity by ten percent.11 “At the top level of athletics, that is the difference between worst and first.”12 While these drugs can be used to enhance an athlete’s performance, they are potentially fatal.13 It is a grand risk for an athlete to take, as he/she has no way of knowing exactly how the drug will affect his/her body prior to using it for the first time.14 Use of performance enhancing drugs has become so rampant that we can rarely turn on the television, read a newspaper, or surf the web without learning about another athlete’s stellar performance being called into question. Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson,15 NFL lineman Lyle Alzado,16 Major League Baseball player Jason Giambi,17 Chinese swimmer Yuan Yuan,18 an entire cycling team in the 1998 Tour de France19; the list goes on and on. The 2006 Winter Olympic Games in Torino had merely begun when eight cross-country skiers were making headlines around the world.20 Athletes were suspended from the games for five days when allegations of performance enhancing drug use surfaced, and tests revealed excessive 9 Id. The dope on banned drugs: Drug Dictionary, available at http://www.cbc.ca/sports/indepth/drugs/glossary/dictionary.html (last viewed January 4, 2006). 11 Athletes and Drug Use, available at http://www.globalpinoy.com/pinoyhealth/ph_fitness/FI120103.htm (last viewed February 9, 2006). 12 Id. 13 Quantum ABC Television: EPO, (March 30, 2000) available at www.abc.net.au/quantum/stories/s112234.htm (last viewed February 9, 2006). 14 Steroid Dangers May Outweigh Performance Boost, (December 13, 2004), available at http://12.31.13.113/healthnews/HealthNewsFeature/hnf121304.htm, (last viewed January 4, 2006). 15 Steroids and Sports are a Losing Combination, (June 1, 1995) available at http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/CONSUMER/CON00107.html (last visited January 4, 2006). 16 Steroid Substitutes: No-win Situation for Athletes, No. FDA 93-1207 (July 1993), available at http://www.openseason.com/annex/library/cic/X0081_ster_sub.txt.html (last visited October 18, 2005). 17 Steroid Dangers May Outweigh Performance Boost, Id. note 14. 18 CBC Sports Online, 10 Drug Scandals, (January 19, 2003) available at http://www.cbc.ca/sports/indepth/drugs/stories/top10.html (last viewed February 9, 2006). 19 Scientists raise spectre of gene-modified athletes, (November 30, 2001), available at http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99991627 (last viewed February 9, 2006). 20 Scandal brewing? Eight XC skiers suspended for excessive hemoglobin, (February 9, 2006), available at http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2006/olympics/2006/02/09/bc.oly.xxc.hemoglobinsu.ap/?section=cnn_mostpopular (last viewed March 2, 2006). 10 3 hemoglobin levels.21 These reports center around athlete reprimand. After all, they are the ones making the choice to use the drug, right? New methods of drug testing22 are proposed and Acts23 promulgated in an effort to curtail the use of these substances. In actuality, these athletes are sick; they have an addiction. Studies indicate that athletes are so driven to win, they get caught up in the fantasy that what they are doing is not wrong, and if it is only a risk to personal safety, they are willing to take that risk.24 This article suggests that the sole focus of liability on the athlete is misplaced. While an athlete should be responsible for his/her actions, if we truly desire to stop this epidemic, responsibility and liability should also be placed elsewhere. As opposed to merely seeking to strengthen drug testing programs, and promulgating “Acts” to regulate Sport, some responsibility and liability should rest with the very entity that creates the drug. It is imperative to stop the problem where it starts. Part I of this article provides an overview of the performance enhancing drug epidemic our world currently faces. Part II discusses the three most commonly used performance enhancing drugs, their FDA approved use, and the reasons athletes choose to use them. Part III traces societal trends in tort litigation, and proposes that we place liability on the manufacturer of these drugs when they should know, or do in fact know that the distributors they are providing these drugs to, are disseminating the drugs for an improper purpose. Part IV summarizes the legal framework that should be applied in negligence claims against drug 21 Id. Edward H. Jurith & Mark W. Beddoes, The United States’ and International Response to the Problem of Doping in Sports, 12 FORDHAM INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT L.J. 461 (2002) (arguing for Federal Anti-Doping programs in the United States, following the lead of other countries such as Australia and Canada. 23 Anabolic Steroid Controlled Substances Acts have been promulgated as needed over the years to reclassify drugs based on prominence and use in society. The most recent was the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004 which amended the Controlled Substances Act of 1990. 24 Mannie, Ken, Performance-Enhancing Drug Abuse, 2000 SCHOLASTIC INC., January 1, 2000, at No. 6, Vol. 69, Pg. 42. 22 4 manufacturers. Finally, Part V concludes the article, proposing that we make it more difficult for athletes to obtain performance enhancing drugs bringing an end to the epidemic. II. The Basics: Commonly-Used Performance Enhancing Drugs The 1950s brought about the use of hormones by athletes in an effort to increase their strength and power. 25 Because hormones are important in organ and tissue development, they continue today as the basis of most performance enhancing drugs.26 As regulations are effectuated, and drug testing methods created, athletes are turning to prescription drugs, in an effort to avoid detection and punishment. The current trend is for athletes to use drugs intended to treat diseases like cancer and anemia, for an unintended purpose such as improvement of their aerobic capacity27 and to build muscle mass and strength.28 Three of the most commonly used performance enhancing drugs among athletes are Erythropoietin (EPO), Human Growth Hormone (hGH), and Anabolic Steroids.29 EPO, hGH, and Anabolic steroids are all hormones – “naturally occurring chemical messengers that regulate many of the body’s functions.”30 The FDA has approved each of these hormones for specific medicinal purposes.31 None of the drugs, however, are approved for the purpose of performance enhancement. Athletes, therefore, are using these legal drugs, for an illegal purpose. 25 Doping in Cycling, supra note 21. Who will win the race?, supra note 6. 27 Scientists raise spectre of gene-modified athletes, (November 30, 2001), available at http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id+ns99991627 (last viewed February 2, 2006). 28 How Performance-Enhancing Drugs Work, available at http:// www.howstuffworks.com/athletic-drug-test.htm (last viewed February 2, 2006). 29 Which drugs are commonly used by elite athletes?, available at http://www.jaconline.com.au/legaloutcomes/hottopics/005-price-of-gold/which-drugs.html (last viewed December 11, 2005). 30 Who will win the race?, Id. note 24. 31 See generally, http://www.fda.gov. 26 5 A. Erythropoietin (EPO) Erythropoietin is a protein hormone that is found naturally in our body.32 It is secreted by the kidneys,33 and stimulates the bone marrow in order to increase red blood cell production.34 Increased red blood cell production in turn, increases the amount of oxygen the blood can carry to the muscles.35 EPO was initially approved by the FDA in June of 1989, to treat anemia.36 It is now approved for use in treatment of patients with AIDS or AIDS-related conditions.37 When used for its intended purpose, EPO has relatively few side effects, such as fever, headaches, and fatigue.38 Amgen, Inc. based in Thousand Oaks, California, and Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation, in Raritan, New Jersey are the two FDA approved manufacturers of EPO.39 Amgen markets the product using the trade name Epogen, while Ortho Pharmaceutical’s trade name is Procrit.40 EPO is commonly used by athletes because the stimulation of red blood cells “increases an athlete’s aerobic capacity and muscle endurance.”41 Sports most associated with the use of EPO are cycling, cross-country skiing, and long distance marathons.42 “The same effect that improves endurance performance also risks the safety of the user.”43 “EPO can cause the blood to become viscous and more prone to clotting.”44 Relatively insignificant side effects for the 32 How Performance-Enhancing Drugs Work, supra note 26. Id. 34 EPO: Illegal, Effective, and Deadly, (2004), available at www.copacabanarunners.net (last viewed October 18, 2005). 35 Australian Sports Drug Agency: Prohibited Substances and Methods, (January 1, 2004), available at http://www.asda.org.au/athletes/banned.htm (last viewed December 11, 2005). 36 EPO for AIDs Related Condition: Food and Drug Administration, (January 2, 1991), available at www.fda.gov (last viewed January 4, 2006). 37 Id. 38 Id. 39 Id. 40 Id. 41 The dope on banned drugs: Drug Dictionary, supra note 10. 42 Id. 43 EPO: Illegal, Effective, and Deadly, supra note 32. 44 Id. 33 6 unintended user are headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash.45 The side effects for the unintended user can, however, be quite severe.46 “Unnaturally high red-blood cell levels increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and pulmonary embolism. The risk is exacerbated by dehydration, which often occurs during endurance exercise.”47 Johannes Draaijer, a young Dutch cyclist, suffered the fatal consequences of using EPO as a performance enhancing drug.48 Six months after finishing twentieth in the 1989 Tour de France, cycling’s most grueling event, Draaijer’s heart ceased beating.49 He was dead at twentyseven, leaving behind a young wife.50 She spoke out about her husband’s death, warning his fellow competitors of the fatal consequences of performance enhancing drugs.51 According to his wife, Draaijer became sick after using the performance enhancing drug, Erythropoietin (EPO).52 Johannes Draaijer is one of many deaths linked to performance enhancing drugs.53 In 1987, along with the availability of EPO, came sudden unexplained deaths among elite cyclists.54 In 1987, “five Dutch cyclists died, followed by two more Dutch riders and a Belgian in 1988, five Dutch cyclists in 1989, and two Dutch and three Belgian riders in 1990. All were regarded as fit and healthy athletes before heart failure or related causes ended their lives.”55 45 Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, Erythropoietin test, (December 2002), available at http://www.healthatoz.com/healthatoz/Atoz/ency/erythropoietin_test.jsp (last viewed February 27, 2006). 46 Id. 47 Australian Sports Drug Agency: Prohibited Substances and Methods, supra note 33. 48 James Deacon & Paul Gains, A Phantom Killer, Maclean Hunter Limited, Nov. 27, 1995, at 58. 49 Id. 50 Id. 51 Id. 52 Id. 53 Bob Ford, EPO Debate Heats Up Before Olympics, The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 11, 2000, at K7533. 54 Ann Westmore, Lack of Volunteers Hampers Drug Research, Canberra Times (Australia), Aug. 11, 1998, at Part A, pg. 7. 55 Westmore, supra note 52. 7 The trend in usage has not subsided, even as a result of these deaths. As recently as 2003, four more professional cyclists died from heart attacks, attributable to use of EPO as a performance enhancing drug.56 B. Human Growth Hormone (hGH) Human Growth Hormone is a peptide hormone57 produced in the anterior section of the pituitary gland.58 It has been used since the 1950s59 to aid growth and development in adolescent children.60 Side effects associated with hGH are gigantism,61 heart disease, and increased oil gland production.62 The FDA approved Protropin, a recombinant hGH manufactured by Genetch, Inc. in San Francisco, California, in October 1985.63 Eli Lily is also a manufacturer of hGH, sold by the trade name, Humatrope.64 It is manufactured in Indianapolis, Indiana, and was approved on March 8, 1990, with its only then accepted use being the treatment of children who have stunted growth due to an inadequate endogenous growth hormone.65 In August 1996, however, the FDA extended their approval for use in adults to treat “somatotrophin deficiency syndrome.”66 Like EPO, hGH is not approved as a performance enhancing drug. 56 John Black, Drug Cheats Off to Flying Start, Nationwide News Pty Limited Courier Mail (Australia), Nov. 24, 2004, at 21. 57 The dope on banned drugs, supra note 10. 58 Will Growth Hormone Prove to be the First “Anti-Aging” Medication?, available at http://www.usdoctor.com/gh.htm (last viewed February 27, 2006). 59 Australian Sports Drug Agency: Prohibited Substances and Methods, supra note 45. 60 Which drugs are commonly used by elite athletes?, supra note 27. 61 Id. (The term [gigantism] means excessive growth.) 62 Australian Sports Drug Agency: Prohibited Substances and Methods, supra note 45. 63 FDA: Human Growth Hormone, (March 12, 1990), available at http://www.fda.gov. (last viewed January 4, 2006). 64 Id. 65 Id. 66 FDA approved HGH?, (October 7, 2003), available at http://www.hghnews.us/p/101%2C212.html (last viewed March 2, 2006). 8 Human Growth Hormone is commonly used by athletes because it stimulates muscle growth, and helps reduce body fat.67 Studies indicate that Insulin Growth Factor 1, a growth hormone, can increase muscle strength by up to twenty-seven percent.68 hGH also aids in recovery following strenuous training.69 It is most commonly used by swimmers,70 but has also been used by athletes such as football players, to increase muscle mass and strength.71 The law prohibits distribution or possession with the intent to distribute hGH for human use other than medically approved uses, pursuant to a physician’s order.72 Violation of this statute is punishable by imprisonment and / or fines.73 C. Anabolic Steroids Anabolic steroids are likely the most commonly known performance enhancing drug. They are similar to the male hormone, testosterone,74 increasing muscle and strength.75 Physicians prescribe anabolic steroids to patients with wasting diseases, and to HIV infected men.76 Athletes most commonly use anabolic steroids to “bulk up” and increase their strength.77 They are also used in an effort to reduce recovery time following an injury.78 Sports commonly associated with use of anabolic steroids are football, sprinting, and bodybuilding.79 Athletes face 67 The dope on banned drugs, supra note 55. Athletes and Drug Use, supra note 11. 69 Id. 70 The dope on banned drugs, supra note 55. 71 Steroid Substitutes, supra note 2. 72 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. §333(e) (2005). 73 Id. 74 FDA Consumer: Are Steroids and Growth Hormones Safe?, (April 1990 update), available at http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/qa-nut10.html (last viewed March 3, 2006). 75 Which drugs are commonly used by elite athletes?, supra note 27. 76 The dope on banned drugs, supra note 55. 77 Which drugs are commonly used by elite athletes?, supra note 73. 78 Id. 79 Athletes and Drug Use, supra note 66. 68 9 a variety of side effects by taking anabolic steroids, ranging from aggression and “masculinizing” side affects,80 to harm to the liver, cardiovascular and reproductive systems.81 More than one hundred anabolic steroids are currently available.82 Regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration, anabolic steroids were placed on the Controlled Substances Act's Schedule III by the Anabolic Steroids Act of 1990.83 The Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004 amended the previous Act, imposing increased penalties for steroid use.84 Unlawful distribution and possession with the intent to distribute anabolic steroids is a federal crime, punishable by up to five years in prison.85 Since penalties were enacted for steroid use, many athletes have avoided anabolic steroids,86 turning to substitutes such as Erythropoietin and Human Growth Hormone. III. Societal Trends in Tort Litigation Public policy is a driving force behind litigation. As society changes and evolves, so too must American Jurisprudence. “Society subjects dangerous instrumentalities to regulatory schemes that safeguard or compensate the public.”87 The imposition of tort liability is an additional means for ensuring adherence to these regulations.88 Historically, tort liability has been imposed in a variety of contexts and industries. 80 Who will win the drugs race?: Catching drug cheats is essential if sports are to be conducted on a level playing field – and if deleterious health effects are to be avoided, supra note 6. 81 Doping in Cycling, supra note 23. 82 Steroid Types, available at http://www.steroids.com/types.asp (last viewed February 27, 2006). 83 FDA: U.S. Drug Abuse Regulation and Control Act of 1970, available at http://www.fda.gov (last viewed March 2, 2006). 84 Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004: 108th Congress, available at http://www.theorator.com/bills108/s2195.html (last viewed December 11, 2005). 85 Food and Drugs, 21 U.S.C. §841 (2005). 86 Steroid Substitutes, supra note 2. 87 Joi Gardner Pearson, Make It, Market I, and You May Have to Pay for It: An Evaluation of Gun Manufacturer Liability for the Criminal Use of Uniquely Dangerous Firearms in Light of In re 101 California Street, B.Y.U.L. Rev. 131 (1997) (quoting Andrew J. McClurg, The Tortious Marketing of Handguns: Strict Liability is Dead, Long Live Negligence, 19 SETON HALL LEGIS. J. 777 (1995). 88 Id. 10 Drugs, used for performance enhancing purposes rather than for their medicinally approved use, are dangerous instrumentalities. These drugs are not only dangerous to the athletes that choose to use them; they also pose a danger to society. Drugs alter personalities; they alter the competitive balance in sports, and can potentially lead to death.89 Because performance enhancing drugs are so prevalent in today’s society and increasingly easy to obtain, imposing a legal duty on those who introduce the drugs into the stream of commerce will compel regulation of distribution, thereby reducing the unintended use of these substances. The most compelling tort claims to assert against drug manufacturers are negligence claims. Based on the legal framework in comparable contexts, negligent distribution is the most viable claim to assert against drug manufacturers. Negligent marketing and negligent entrustment are potentially viable claims as well. A. A Claim Based on Negligence: The Basics Negligence is “conduct which falls below the standard established by law for the protection of others against unreasonable risk of harm.”90 Common Law Negligence consists of three elements: (1) a legal duty owed by one person to another; (2) a breach of that duty; and (3) damages proximately resulting from the breach.91 Establishing that the manufacturer has a duty is the cornerstone of establishing a prima facie case in negligence.92 Duty is the care a reasonable person would take under the same or similar circumstances.93 It is sourced in “existing social values and customs.”94 Though there is no standard equation for establishing a duty, “the most commonly applied test used to determine 89 The dope on banned drugs: Drug Dictionary, supra note 10. RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TORTS §282 (2005). 91 84 AM. JUR. Trials §105 (2005). 92 Christie, George C. & James E. Meeks, et. al., Cases and Materials on The Law of Torts 234 (West Publishing Co. 1997) (1938). 93 Dobbs, Dan B., The Law of Torts, Hornbook Series, § 115 (2000). 94 Mullins v. Pine Manor College, 389 Mass. 47, N.E. 2d 331 (1983) (quoting Schofield v. Merrill, 386 Mass. 244, 435 N.E. 2d 339 (1982)). 90 11 whether a legal duty exists is the ‘foreseeability’ standard.”95 This standard turns on whether the harm caused was a “reasonably foreseeable” consequence of the actor’s actions.96 The foreseeability standard was enunciated in the landmark decision, Palsgraph v. Long Island Railroad Co.97 Merely the result must be foreseeable, the manner in which the incident occurs need not be.98 Foreseeability, however, is not the only factor to consider. Other relevant factors in determining whether a duty exists are the “morality and justice of imposing liability, and society’s ideology of where to direct the loss.”99 Moreover, the existence of a third party complicates the finding of a duty to exist. As a general rule, the defendant has no duty to control third party actions.100 The rule ceases to apply, however, when a “special relationship” exists between the parties.101 A special relationship may exist by means of a contract, or may exist solely because of the kinship between the parties. 102 When a special relationship exists between the actor and the third person, the law of torts imposes a duty on the actor to exhibit control over the third person’s conduct.103 The determination of whether a duty exists, and the extent and scope of this duty are questions of law for the court.104 Duty is typically established either by statute promulgated by the Legislature, or by the court where “clearly supported by public policy.”105 When establishing a duty based on public policy, courts consider factors such as: “the foreseeability of harm to the plaintiff, the degree 95 Pearson, supra note 85, at 153. Lavo v. Medlin, 705 S.W. 2d 562 (1986). 97 Doug Morgan, What in the Wide, Wide World of Torts is Going on? First Tobacco, Now Guns: An Examination of Hamilton v. Accu-Tek and the Cities’ Lawsuits Against the Gun Industry, 69 MISS L.J. 521 (1999). 98 St. John Bank & Trust Co. v. City of St. John, 679 S.W. 2d 399 (1984) (quoting Prosser & Keeton, Torts §44 at 317). 99 Morgan, id. note 95, at 543. 100 Greater Houston Transportation Co. v. Kurt Steven Phillips, 801 S.W. 2d 523 (1990). 101 Hergenrether v. East, 61 Cal. 2d 440, 393 P.2d 164, 39 Cal. Rptr. 4 (1964). 102 California Civil Practice: Torts §1.2 (2005). 103 See Greater Houston Transportation Co., 801 S.W. 2d at 525. 104 Merrill v. Navegar, 26 Cal. 4th 465, 28 P.3d 116, 110 Cal. Rptr. 2d 370 (2001). 105 Id. 96 12 of certainty that the plaintiff suffered injury, the closeness of the connection between the defendant’s conduct and the injury suffered, the moral blame attached to the defendant’s conduct, the policy of preventing future harm, the extent of the burden to the defendant and consequences to the community of imposing a duty to exercise care with resulting liability for breach, and the availability, cost, and prevalence of insurance for the risk involved.”106 B. Remaining Elements of Negligence To determine whether the defendant breached the duty of care owed to the plaintiff, “the magnitude of the harm likely to result from [a] defendant’s conduct must be balanced against the social value of the interest which he is seeking to advance, and the ease with which he may take precautions to avoid the risk of harm to plaintiff.”107 Finally, establishing a prima facie case in negligence requires proof of causation.108 Causation can be broken down into two prongs: (1) Causation in fact; and (2) Proximate Cause.109 “Causation in fact” requires that the defendant’s conduct caused the plaintiff’s harm or injury.110 Sine qua non is the test most often employed to establish causation.111 This means, “but for” the act of the defendant, the plaintiff would not have been injured.112 When this rigorous standard is not met, if it can be proven that the defendant’s act was the “substantial cause or causes” of the event that occurred, then in most jurisdictions causation will be met.113 Proximate cause is the test for legal cause the judge uses in deciding whether the plaintiff is within the scope of foreseeable harm that the defendant’s actions created. Proximate cause concerns itself with policy, asking “the larger, more abstract question: Should the defendant be 106 See Merrill, 26 Cal. 4th at 477. Ileto v. Glock, Inc., 349 F.3d 1191 (Ninth Cir.) (2003). 108 Christie, George C. & James E. Meeks, et. al., supra note 89, at 234. 109 Id. 110 See id. at 235. 111 Id. 112 Id. 113 Id. 107 13 held responsible for negligently causing the plaintiff’s injury?”114 The judge will consider whether the act was foreseeable, and whether intervening or superceding causes were instead the reason for the plaintiff’s harm. In some jurisdictions, proximate cause requires the cause of harm to be substantial; it need not be the sole cause of the harm, however.115 Other jurisdictions employ a stricter standard and require proof that the defendant’s action (or inaction) was a probable cause of the harm.116 As with establishing the existence of a duty, intervening factors such as third party actors, do not necessarily bar the defendant’s liability.117 Rather, as long as the intervening force is foreseeable, it is within the scope of the defendant’s negligence.118 C. Theories of Negligence Negligent Distribution, Negligent Marketing, and Negligent Entrustment are viable claims to assert against a drug manufacturer. While negligent distribution and negligent marketing claims are often asserted in tandem, and even confused, it is necessary to accurately distinguish between these theories of negligence. The rationale behind the theories is for individuals to avoid foreseeable risks of harm to others by using reasonable care.119 Negligent Distribution A manufacturer is liable for “negligent distribution” when it fails to use “reasonable means” to regulate the sale of its product.120 Negligent Marketing A manufacturer is liable for “negligent marketing” when it markets its product in a manner that increases a product’s inherent risk to consumers and third parties.121 There are 114 Evan v. Hughson United Methodist Church, 8 Cal. App. 4th 828, 10 Cal. Rptr. 2d 748 (1992). See Iteto, 349 F. 3d at 1206. 116 Scafidi v. Seiler, 119 N.J. 93, 574 A.2d 398, (1990). 117 Id. 118 Tenney v. Atlantic Associates, 594 N.W. 2d 11 (1999) (quoting RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS §449, cmt. b, (2005)). 119 Morgan, supra note 95, at 6. 120 See Ileto, 349 F. 3d at 1197. 115 14 currently three aspects of negligent marketing claims: (1) negligent marketing of unusually dangerous weapons; (2) negligent advertising of handguns to criminal consumers; and (3) negligence in the failure to take “reasonable precautions to minimize the risk of handguns being sold to those likely to misuse them.”122 Negligent Entrustment A manufacturer is liable for “negligent entrustment” when it entrusts its product to a distributor with the knowledge that the product is likely to be used in an improper or dangerous fashion. 123 D. Liability in Comparable Contexts To establish a legal framework for drug manufacturer liability, it is necessary to examine manufacturer liability in comparable contexts. This article suggests a legal framework based on similarities and persuasively distinguishable characteristics in liability imposed on manufacturers of guns, pesticides & fungicides, chemicals, and slingshots. Imposition of liability on drug manufacturers may arise in different contexts, depending on the drug involved, and penalties associated with its unintended use. For example, the Controlled Substances Act of 1990 placed anabolic steroids on the Schedule III list of controlled substances, thereby imposing a criminal penalty on individuals distributing steroids for unintended uses.124 Distribution and subsequent acquisition of drugs carrying criminal penalties can be analogized to the manufacture and distribution of guns to illegal purchasers. 121 Richard C. Ausness, Tort Liability for the Sale of Non-defective Products: An Analysis and Critique of the Concept of Negligent Marketing, 53 S.C. L. Rev. 907 (2002). 122 Andrew Jay McClurg, Symposium: Triggering Liability: Should Manufacturers, Distributors, and Dealers Be Held Accountable for the Harm Caused by Guns?: The Tortious Marketing of Handguns: Strict Liability is Dead, Long Live Negligence, 19 SETON HALL LEGIS. J. 777 (1995). 123 National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v. Acusport, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 435 (2003). 124 FDA: U.S. Drug Abuse Regulation and Control Act of 1970, supra note 81. 15 Today, the gun industry is at the forefront of tort litigation.125 The 1980s brought about the theory of negligent marketing as a possible basis for recovery in gun manufacturer liability cases.126 Negligent distribution and negligent entrustment claims were often asserted in tandem with the negligent marketing claim. Early cases proposing these theories were not well accepted by courts, as they found no duty owed by manufacturers, thereby precluding a prima facie case in negligence.127 The late 1990s brought about a seemingly changing attitude in the New York and California court systems, however this came to a screeching halt in the early 2000s when decisions in Hamilton v. Accu-Tek and Merrill v. Navegar were overturned.128 Perhaps the attitude is again on the rebound as illustrated by Ileto v. Glock.129 Courts are at least allowing the claims to withstand the biggest hurdle of establishing that manufacturers have a duty. Liability was established in Ileto v. Glock, when Lilian Ileto, decedent’s mother, joined with four minors shot in a Jewish Community Center by a deranged gunman (prohibited from gun possession130), and was allowed to bring suit against gun manufacturers, distributors, and dealers. 131 Plaintiffs asserted public nuisance and negligence claims against the defendants. The negligence claim is based on the argument that “through their distribution scheme, defendants created an illegal secondary market for guns targeted at illegal users.”132 In reversing the lower court’s dismissal of the negligence claim against defendant, Glock, Inc., the Court of Appeal found that the plaintiffs sufficiently alleged “reasonable foreseeability,” and proved the causal connection between the manufacturers’ negligence and the harm suffered.133 125 Andrew M. Dansicker, The Next Big Thing For Litigators, 37-AUG MD. B.J. 12 (2004). Ausness, supra note 119, at 918. 127 Id. 128 Id. 129 Ileto v. Glock, 349 F. 3d. 1191 (2003). 130 Id. at 1204. 131 Id. at 1196. 132 Id. at 1201. 133 See Ileto, 349 F. 3d at 1203. 126 16 Reasonable foreseeability was established by plaintiff’s allegations that Glock, a gun manufacturer, targeted states that have less stringent gun laws so that guns will be sold there, then distributed to the neighboring states with more stringent laws.134 Reasonable foreseeability was further established by evidence that the harm suffered by the plaintiffs “is the kind of harm that is reasonably foreseeable when a person who is forbidden under federal law from purchasing guns is able to purchase an arsenal as a result of the manufacturer’s distribution system.”135 The court found a duty to exist, and that duty was thereby breached because the defendants continued to supply distributors they knew distributed in crime-ridden areas, and because defendants failed to contract with the distributors to prohibit sales in areas of crime.136 Further, manufacturers failed to provide training so that distributors would avoid selling to illegal purchasers.137 Taking public policy into consideration, the court found a duty to exist, because the “social value of this practice to the defendants is outweighed by the health and safety interest of potential victims of gun violence at the hands of prohibited purchasers.”138 The court concluded causation was met because Glock could have prevented the harm.139 “The key … is that the defendant’s relationship with either the tortfeasor or the plaintiff places the defendant in the best position to protect against the risk of harm.”140 Defendants argued that an intervening act by the gunman should absolve manufacturer liability.141 The court disagreed, and held that the intervening act was foreseeable because Glock’s negligent distribution and marketing targeted people like the gunman.142 Plaintiffs therefore, established a prima facie case 134 Id. at 1197. Id. at 1205. 136 Id. 137 Id. 138 Id. at 1206. 139 Id. at 1207. 140 See Ileto, 349 F. 3d at 1207. 141 Id. at 1209. 142 Id. 135 17 in negligence with regard to defendant, Glock. The case was remanded to the lower court for further proceedings.143 The court recently employed a similar rationale in District of Columbia v. Beretta.144 Nine plaintiffs in the instant action appealed the dismissal of their suit against gun manufacturers and distributors.145 Plaintiffs sued on several theories, one of which was negligence.146 They argued that defendants should be held criminally liable because misuse of defendant’s guns led to their injury, or to the death of a family member.147 Similar to Ileto, plaintiffs allege that defendants failed to enter their product into the market in a manner that would prohibit the guns from reaching the hands of criminal users.148 Dissimilar to Ileto however, the court declined to find the requisite elements met in order to allow plaintiffs’ action.149 It reasoned that in the case of third party intervention, a special relationship must exist to establish that defendant had a duty.150 It then declined to extend the special relationship distinction because plaintiffs failed to suggest a “reasonable way that gun manufacturers could screen the purchasers of their guns to prevent criminal misuse.”151 Additionally, it found the chain of causation to be too attenuated.152 Drug manufacturers’ act of negligently distributing their product is analogous to the negligent distribution of guns. Just as the distribution scheme in the gun industry leads to an illegal secondary market targeted at illegal users,153 the lack of regulation and haphazard 143 Id. at 1217. District of Columbia v. Beretta, 872 A.2d 633 (2005). 145 Id. at 638. 146 Id. at 637. 147 Id. at 638. 148 Id. at 638. 149 Id. at 641. 150 Id. at 640. 151 Id. 152 Id. at 644. 153 Id. at 1202. 144 18 distribution of prescription drugs leads to acquisition of these drugs by unintended users, thereby fueling the performance enhancing drug epidemic. In both contexts, the manufacturers continue to supply their product with the knowledge that the distribution will likely, or in fact does, cause their product to fall into the hands of misusers. Moreover, the Ileto court imposed a duty on gun manufacturers because of the value that their decision would bring to society. 154 Imposing a duty on drug manufacturers would similarly render benefit to today’s society. In holding drug manufacturers responsible for their distribution scheme, society would derive value from more restricted access to drugs for non-prescription uses. This would in turn reduce the number of individuals able to easily access the drugs, thereby causing less misuse and fewer fatalities. It too will reinstill the value of hard work, competition, and true heroism in sports by causing athletes to strive for excellence merely through physical performance and stamina rather than relying on drugs for enhanced performance. It will eliminate the competitive imbalance caused by the use of these drugs, and in turn reinstate the legitimacy of sport. Dissimilar to the harm caused by the manufacturer’s actions in the drug industry, in the gun context the injured party, estate, or even a city is typically suing the gun manufacturer because of the actions of a third party shooter, who used the gun to injure the victim. The drug context is distinguishable because the injured athlete or the athlete’s estate if deceased, is not suing the drug manufacturer because of the unlawful actions the third party distributor took against the athlete. If the act of the distributor was in fact unlawful, it was at the request of the athlete, as opposed to the athlete being an unknowing third party victim as is the case with gun plaintiffs. Moreover, the malicious act of loading a bullet into a gun and shooting another individual with the intent to harm is extremely different from risking your own personal health and safety by using a drug to enhance your performance in a sporting event. This distinction 154 Id. at 1205, 1206. 19 obviates the obstacle faced by the court in establishing “reasonable” foreseeability sufficient to impose a duty on defendant manufacturers in District of Columbia v. Beretta. Further, the court struggles with the question of where liability ever ends in the gun context, because the chain of causation is so attenuated.155 It is difficult to establish a duty, and hold a gun manufacturer liable for distribution because there are so many intervening factors in the chain. Guns are sold, and re-sold making it nearly impossible to track the exchanges between owners once the product actually enters the stream of commerce. Again this is distinguishable from the drug industry. To obtain performance enhancing drugs, the athlete either seeks a physician’s assistance or finds an Internet website selling drugs. The latter is the more likely source being that it is incredibly simple to purchase over the Internet. With either means of purchase, however, the chain of causation is far less attenuated in the drug context because once purchased, the drugs are consumed, as opposed to being sold and re-sold like guns. The less attenuated chain of causation makes it easier to track the drug distribution back to the manufacturer, thereby obviating the difficulty the courts faced in linking gun manufacturers to the negligent distribution of guns. Moreover, the ability to purchase hGH and certain anabolic steroids on the Internet makes tracing distribution back to specific manufacturers relatively simple. The websites used to order these drugs often list the manufacturers that distribute to them. In such instances, there is no uncertainty as to what manufacturer initiated the negligent act of distributing their product to known unintended users. Negligence therefore ensues when the manufacturer fails to take adequate precautions in distributing their drugs to pharmacists and physicians who in turn provide drugs to athletes to enhance their performance rather than prescribing the drug for its FDA approved purpose. 155 Hamilton v. Beretta, 96 N.Y. 2d 222, 750 N.E. 2d 1055, 727 N.Y.S. 2d. 7 (2001). 20 Courts also must walk a fine line in not impeding individual rights with regulations in the gun industry. The court must balance the right to bear arms under the Second Amendment with the desire to keep such dangerous instrumentalities out of the hands of criminals, so as not to cause harm to disinterested third parties. A similar concern is simply not present in the drug industry. Restrictions on distribution will not infringe on personal rights, and it will not hinder intended users from obtaining drugs necessary for treatment of their disease. Rather, regulation in the drug industry will serve to curb unintended use, benefiting society, as opposed to inhibiting personal liberties. Because of the distinguishing characteristics of the drug industry, an alternative and perhaps stronger argument for imposing liability on drug manufacturers is to argue that a chain of negligence stemming from the manufacturer’s initial negligent act, absent a third party criminal act, is responsible for the plaintiff’s injury. This theory is plausible regardless of whether the negligence led to a subsequent act criminal in nature. The manufacturer remains liable for his initial negligent act as long as the subsequent negligent acts were foreseeable to him at the time his negligence ensued.156 Claims based on negligent distribution theories are relatively few in number. While establishing liability based on negligence in the face of an intervening criminal act has only recently prevailed as evidenced in Ileto, negligent distribution claims without the intervening third party criminal element have proven even more successful over the years. Absent third party action, negligence takes one of two forms. The negligent act of the manufacturer may lead to a violation of some law or statute. In the alternative, the negligence need not lead to a subsequent illegal act for the original negligent manufacturer to be held liable. 156 Christie, George C. & James E. Meeks, et. al., supra note 106, at 329. 21 If the drug used for performance enhancing purposes is a Schedule III drug, criminal penalty will be imposed for unintended distribution.157 Therefore, in the absence of an intervening third party, when the manufacturer’s negligent action leads to illegal distribution and use of the drug, the legal framework in Suchomajcz v. Hummel Chemical Co.158 should be applied. The Suchomajcz court held that distribution of a chemical to a foreseeable misuser of the product was sufficient grounds for a negligent distribution claim.159 In Suchomajcz v. Hummel Chemical Company, plaintiffs alleged chemical manufacturer, Hummel, “knew or should have known” that the company they were distributing chemical components to intended to use the chemicals to manufacture and sell firecracker assembly kits.160 These firecracker kits were illegal.161 The Suchomajcz Court based its decision partially on policy.162 It reasoned that the manufacturer knew that the distributor intended to misuse the chemicals.163 Moreover, the “social utility of knowingly selling chemicals for illegal use is minimal; the social consequences of such sales may be devastating.”164 Based on this foreseeable misuse, a duty to warn arose.165 Hummel’s knowledge and inaction was sufficient ground for the negligent distribution claim to prevail.166 Alternatively, distribution and use of drugs, such as EPO, are not Schedule III drugs, thus not carrying a criminal penalty. Drugs such as EPO, therefore should follow the legal framework established in E.I. Du Pont De Nemours & Co. v. Aquamar S.A.167 In Du Pont, a Du 157 Food and Drugs, supra note 83. Suchomajcz v. Hummel Chemical Company, 524 F. 2d 19 (Third Cir.) (1975). 159 Id. at 28, 29. 160 See Suchomajcz, 524 F. 2d at 26. 161 Id. 162 Id. 163 Id. 164 Id. 165 Id. at 28. 166 Id. 167 E.I. Du Pont De Nemours and Company v. Aquamar S.A, 881 So. 2d 1 (2004). 158 22 Pont manufactured fungicide, Benlate, was applied to banana farms to prevent the spread of Black Sigatoka, a disease, in Ecuador.168 Neighboring shrimp farms began to suffer loss of their shrimp because they relied on river water, which was being contaminated by the Benlate.169 Plaintiffs sued Du Pont for negligently distributing Benlate.170 There were two reasons for asserting this claim.171 Plaintiff alleged Du Pont “was negligent ‘in advising and instructing Ecuadorians that Benlate should be widely applied in combination with the fungicides Tilt and Calixin.’”172 Plaintiffs also alleged Du Pont acted or failed to act, following its notification of the government that the fungicide was linked to the shrimp deaths.173 A jury awarded plaintiff more than $12 million in damages for Du Pont’s negligent distribution of Benlate, however on appeal, the court held plaintiff’s claims were preempted by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act.174 Regardless of whether the misuse is governed by criminal penalty, the courts apply a very comparable rationale in the foregoing cases, indicating the cases turn on foreseeability, causation, and public policy. Similar to Hummel Chemical Company and the Du Pont Fungicide Manufacturer, drug manufacturers should be held liable for distributing their drugs to distributors that they “know or should have reason to know” intended to provide the drugs to unintended users. Moreover, the distributor of Benlate in Du Pont was liable in part because the manufacturer failed to properly notify the government once they had knowledge that their product was causing death of shrimp in nearby waters.175 While the Du Pont case is distinguishable because the banana farmers were legitimate users of Benlate, this distinction does 168 Id. at 2. Id. 170 Id. at 3. 171 See E.I. Du Pont De Nemours and Company, 881 So. 2d at 3. 172 Id. 173 Id. 174 Id. at 2. 175 Id. 169 23 not preclude use of Du Pont as precedent in the drug manufacturer context, because Du Pont’s negligence was predicated in part on their failure to act. Du Pont neglected to notify the government once they had knowledge that the shrimp deaths were caused by their product. Liability similarly should follow in drug manufacturer cases. It is simply not a viable defense for manufacturers to argue that they don’t have knowledge of the performance enhancing drug epidemic that our world currently faces. A manufacturer’s knowledge that their drug is potentially being used for unintended purposes, should render a duty on the manufacturer to track its sales, and ensure legitimacy of its distributors. Whether supplying a pharmacy, either tangible or on-line, manufacturers should be responsible for directing their products to distributors who will abide by FDA regulations, thereby precluding distribution to unintended users. Regulation of distribution to legitimate distributors could be achieved by manufacturers performing background checks on distributors prior to selling their product. Further, the same policy considerations applicable in Suchomajcz are persuasive in the drug context. The Suchomajcz court compared the “social utility” to the “social consequences” of the manufacturer’s actions.176 In the drug context, the social utility of selling prescription drugs to athletes to enhance their performance is negligible. The social consequences of these sales, on the other hand, are devastating to society. Legitimacy of America’s favorite pastime is being called into question; athletes are dying, and use of these drugs is extending to today’s youth. The legal framework employed in these negligent distribution cases, therefore, should also serve as the framework for holding drug manufacturers liable for their negligent distribution of drugs used for performance enhancing purposes. 176 See Suchomajcz, 524 F. 2d at 25. 24 Negligent marketing and negligent entrustment are also viable claims to assert against a drug manufacturer. Asserted in tandem with a negligent distribution claim, they are even stronger, as the claims illustrate the full realm of the manufacturer’s negligence. Moning v. Alfono177 provides a legal framework for negligent marketing and entrustment claims. Nearly twenty years ago, the Moning Court was presented the legal question, whether a manufacturer of slingshots can be held liable for negligent marketing.178 Considering this issue, the court reasoned that the theory of common law negligence was established by judges, and it was necessary for the court to consider this issue because in the absence of action by the Legislature, the court must adjudicate, either developing or limiting governing law.179 The plaintiff in Moning, a twelve year old boy, was blinded when his playmate hit him in the eye with a pellet from his slingshot.180 Plaintiff’s claim based on negligent marketing, alleges the manufacturer, wholesaler, and retailer are liable for marketing the sale of slingshots directly to children.181 The Moning court found a duty to exist, establishing that the manufacturer and wholesaler of a product are liable “by marketing the product,” and “owe a legal duty to those affected by its use.”182 Plaintiff also asserted a claim based on negligent entrustment.183 He argued, “One who supplies directly or through a third person a chattel for the use of another whom the supplier knows or has reason to know to be likely because of his youth, inexperience, or otherwise, to use it in a manner involving unreasonable risk of physical harm to himself and others whom the supplier should expect to share in or be endangered by its use, is subject to liability for physical harm resulting to them.”184 177 Moning v. Alfono, 400 Mich. 425, 254 N.W. 2d 759 (1977). Id. at 432. 179 Id. at 436. 180 Id. at 432. 181 Id. 182 Id. at 433. 183 Id. at 444. 178 25 The Court of Appeal reversed the trial court’s directed verdict for the defendants, and remanded the action based on its finding that the manufacturer owed a duty to its consumers.185 Breach of the duty remained a question for the jury. 186 The gun industry attempted to use Moning as precedent for establishing negligent marketing in Caveny v. Raven Arms Co.187 The Caveny court found Moning distinguishable, and disallowed its application.188 It reasoned that the class of misusers in Moning was “readily identifiable” because they were children, as opposed to an unlimited class of “gun users”.189 Further, it reasoned that means for prohibiting distribution to the misusers was viable in Moning,190 whereas applied to gun manufacturers, it is difficult to “conceive of a method of distribution by which handgun manufacturers could avoid the sale of its product to all potential misusers”.191 Unlike Caveny’s unsuccessful attempt to follow Moning’s precedent, based on the Moning Court’s rationale, drug manufacturers will be more successful in asserting Moning as precedent. A child’s naivety and “blindness” to the danger of the toy because of their desire to use the toy is analogous to an athlete’s uninhibited use of performance enhancing drugs. A slingshot is an object that is appealing to a child. The child fails to see the inherent danger of the slingshot because of the child’s desire to play with the fun toy. Such is the case with the professional athlete. The athlete fails to see the danger in misusing a drug because his/her focus is on enhanced performance promised by use of the product. The user in each situation is 184 Id. quoting RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS §390. See Moning, 254 N.W. 2d at 432. 186 Id. 187 Caveny v. Raven Arms Co., 665 F. Supp. 530 (S.D Ohio, Western Division) (1987). 188 Id. at 533. 189 Id. 190 Id. 191 Id. at 534. 185 26 blinded of the product’s danger by his/her desire to use the product. The benefits of the drug resonate in the athlete’s mind, drowning out the recognition of the drugs’ danger. The athlete is a child; the performance enhancing drug, his toy. IV. Bringing It All Together: The Framework for Liability Foreseeability, causation, and public policy support imposing a duty on drug manufacturers to responsibly distribute their drugs. News reports, personal testimonials of athletes and their families, and even athlete deaths render misuse of drugs such as EPO, hGH, and Anabolic steroids foreseeable to drug manufacturers. Further, causation is met, as drug manufacturers are certainly a substantial factor in an athlete’s ability to obtain these drugs. Finally, public policy supports imposition of liability on drug manufacturers. Athletes are dying for their sport, legitimacy of world records are being called into question, and perhaps even more tragic, this epidemic is spreading to today’s youth. Athletes are so blinded by their desire to be the best that they fail to realize the grave consequences associated with their actions. Moreover, drug manufacturers are in the best position to remedy this problem. Athletes are being held accountable for their actions. Why should drug manufacturers not be held accountable? This article suggests that a drug manufacturer’s fear of liability would detour negligent conduct, thereby decreasing use of drugs for improper purposes. Only imposing liability on the athlete by creating new drug tests and penalties merely encourages athletes to search out new performance enhancing drugs, such as EPO and hGH that are extremely difficult to detect. If instead of reprimanding the athlete and trying to regulate his/her conduct, we target the drug manufacturer, athletes would have a much more difficult time obtaining the drug in the first place. Lets stop the problem where it starts. We need to negate the ability for the athlete to 27 obtain the drug for a non-prescription purpose, rather than reprimanding the athlete once they are determined a user. The legal framework exhibited in comparable contexts illustrates that negligent distribution is a viable claim against drug manufacturers. Negligent distribution is a widely applicable concept in this industry, and should be asserted against manufacturers who fail to monitor and regulate the distributors to whom they provide drugs. In order to prove successful based on cases in related contexts, the manufacturer must have a duty. The court should have little difficulty in finding such a duty to exist. A drug manufacturer has a duty to regulate distribution because undoubtedly the manufacturers have knowledge of off-label uses of their drugs. The latest scandal, announced in the 2006 Winter Olympics caused the performance enhancing drug epidemic to re-emerge in news headlines around the world. The knowledge of this misuse, and society’s need for regulation, not only for protecting the health of athletes, but also to reinstill the value and legitimacy in sport, imposes a definite duty on drug manufacturers. Arguably, because certain drugs such as EPO, hGH, and anabolic steroids are the drugs most commonly abused, thus most frequently reported on in the news, manufacturers of these drugs should have a heightened awareness and an even more compelling duty to protect their consumers. Though negligent distribution is likely the most viable claim to assert against drug manufacturers, negligent marketing is also a potentially viable claim. Negligent marketing in the drug context is proven when the manufacturer of a drug promotes that drug in a way that encourages misuse. Evidence does not suggest that the original manufacturers of FDA approved drugs such as Amgen and Ortho Pharmaceuticals market their drugs, targeting unintended users. Advertisements and order forms easily accessible on the Internet, however, suggest that some 28 generic drug manufacturers target unintended users such as athletes, making it so simple to obtain these drugs that once ordered, they can be delivered via Federal Express directly to your doorstep. Take for example the anabolic steroid, Deca-Durabolin, which is FDA approved to increase bulk and muscle mass in cancer patients. When the patent expired on Deca, generic makers swooned, and Deca is currently being manufactured by numerous generic companies. Some manufacturers of generic versions of Deca should be held liable for negligent marketing because they produce the generic drug under the guise that it is for a varied use, such as to increase muscle mass in animals. From the picture on the label, however, to the usage indications, the drug is tactically marketed to an athlete. These manufacturers should also be held liable for negligent distribution. The websites selling these generic drugs are selling to athletes. This is apparent by the pictures on the websites, the disclaimers, and the order procedure. Moreover, some websites actually list the manufacturers supplying drugs to these Internet distributors, therefore it is easy track the manufacturers and allocate liability. Finally, negligent entrustment may also be asserted against manufacturers. Applying the court’s rationale in Moning, a manufacturer should be held liable when they have knowledge that the distributors they provide their drug to intend to negligently distribute to unintended users. Failure of manufacturers to use diligence in conducting background checks on their purchasers results in a chain reaction, saturating the market with drugs that are used for an unintended purpose. The potential for manufacturers to be held liable for negligent entrustment would serve as a deterrent to manufacturers, and cause manufacturers to be more selective in their distribution. The manufacturer is in the best position to determine what distributors to entrust 29 their product to, and thoughtful entrustment will thereby eliminate the initial negligent act by the manufacturer, relinquishing the manufacturer’s liability. V. Conclusion Society has dictated the need for imposition of liability on drug manufacturers for their negligent distribution, marketing, and entrustment of drugs used for performance enhancing purposes. Imposition of liability on manufacturers will better society and reduce risks to athletes by making it much more difficult to obtain prescription drugs for performance enhancement. Holding manufacturers liable in addition to holding athletes responsible for their actions will help to end the performance enhancing drug epidemic that plagues the world, by stopping the problem where it starts. 30