The Formalist Approach in Practice

advertisement

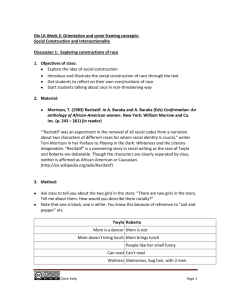

1 Dr. M. Ayuso English 300—Spring 2008 Short Paper #1: The Formalist Approach in Practice The Ambiguity of Race in Toni Morrison’s “Recitatif” Toni Morrison’s “Recitatif” takes a close look at conceptualizations of race in a racially segregated America. The story looks at the relationship between two women – one black, one white – over time, beginning from their meeting as little girls. It builds upon racial ambiguity to help develop a theme about how race is applied to individuals; it never concretely discloses which character, Twyla or Roberta, is black and which is white. The ambiguities of race and the paradox of the similarities between the two women in the face of racial divides helps to explore a universally-relevant theme: that race is an artificially-constructed apparatus that masks the true humanity of all people. At the beginning of the story, the racial differences between Twyla and Roberta are noted, but the commonalities they share are more striking. Most notably, both end up in a children’s shelter because of their mothers. “My mother danced all night and Roberta’s was sick,” explains Twyla, the narrator, at the very beginning of the story. She further comments, “That’s why we were taken to St. Bonny’s,” the shelter (159). Twyla establishes the friendship she develops with Roberta as not based on differences but on a major similarity that is inherently non-racial. Both have mothers who are unable to take care of them but for different reasons. Both the common ground that Twyla and Roberta share and the pervasive topic of race are seen in the mothers as well. Both mothers have attempted (perhaps subconsciously) to instill in their daughters a sense of prejudice against the other race. Mary, Twyla’s mother, educates her to believe that people of Roberta’s race “never [wash] their hair” and “[smell] funny” (160). Twyla acquiesces, 2 noting that Roberta does indeed smell funny. Later, when the two mothers meet through their daughters, Roberta’s mother refuses to shake Mary’s hand, prompting Mary to call her a “bitch” (163). The similarities of Twyla and Roberta’s situation because of their mothers and the racial tensions that exist because of their mothers provide a paradox that helps to extract a theme revolving around racial tensions that should not exist. A racial uneasiness develops more clearly between the two girls when they next meet, coincidentally, at the Howard Johnson’s where Twyla works, but the racial identity of both continues to remain ambiguous. Twyla’s working class job at the hotel is not a clearly defined racial occupation, nor is Roberta’s cold reception of the other a specifically white or black attitude. The allusion to famed African-American rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix gives little indication as to which character might be what race but instead prolongs the racial ambiguity of the story. Hendrix was an iconic counterculture figure that appealed to both blacks and whites. Thus, Roberta’s attempt to see Hendrix and Twyla’s ignorance of who he is in the end provides few clues to the skin color of the characters. In fact, he is perhaps symbolic of similarities that people, including Roberta and Twyla, share over color lines. Later, the two meet by chance in a grocery store, but the racial ambiguity of both remains. Both are now married, but the names of their husbands, Twyla’s James and Roberta’s Kenneth, as well as Twyla’s son, Joseph, provide no real contextual clues about the race of either woman, assuming both married men of their own race. Kenneth, James, and Joseph are names that are often given to men of both races. Roberta’s newfound wealth through her husband, who likely works for IBM, including the fact that she lives in the well-to-do suburb of Annandale, that she has a limousine with a “Chinaman” 3 for a driver (167), and that she buys “fancy water” (166) suggest that she might be white, as these luxuries are often seen as stereotypically white and “yuppie.” This, however, would discount the upward mobility of many blacks in the post-civil rights era. It is very conceivable that Roberta could be an upper-class black woman and Twyla a middle- or lower-class white woman. Perhaps most striking, though, is the argument that the two have over Maggie, the old woman who worked at St. Bonny’s, while protesting on opposite sides the bussing of their children to different schools, which itself helps to enhance the racial tension enveloping the story. The main crux of the argument is over the race of Maggie, and in a sense, Maggie represents a shared history between the two women that has come to be seen differently by the two: “Maybe I am different now, Twyla [says Roberta]. But you’re not. You’re the same little state kid who kicked a poor old black lady when she was down on the ground. You kicked a black lady and you have the nerve to call me a bigot.” The coupons were everywhere and the guts of my purse were bunched under the dashboard. What was she saying? Black? Maggie wasn’t black. “She wasn’t black,” I said. “Like hell she wasn’t, and you kicked her. We both did. You kicked a black lady who couldn’t even scream.” “Liar!” (172) The two cannot agree over Maggie’s race. Interestingly, Roberta, the wealthier woman who might easily be seen as the white one, accuses Twyla of bigotry, of accosting an old “black woman.” Roberta’s statement helps to continue the racial ambiguity of two characters. Paradoxically, their sense of a shared history, represented in the racially ambiguous Maggie, is coming apart while their own racial identities are still far from clear. 4 In the end, when the two meet for the last time in the story, Maggie’s race becomes a moot issue. What becomes important is that Maggie was a human being, one who could not speak and disclose her own racial identity. “I really did think she was black,” Roberta tries to explain to Twyla. “But now I can’t be sure. I just remember her as old, so old” (174). Maggie embodies the children’s home and the racial blurring that brought the two girls together in the first place. In the end, they do not care what race she is; they care about her as a person, which the very last line of the story, spoken by Roberta, tells so eloquently: “Oh shit, Twyla. Shit, shit, shit. What the hell happened to Maggie?” (175). To know what happened to Maggie is for them to know what will happen to them and to their friendship. The racial labels prove meaningless. 5 Works Cited Morrison, Toni. “Recitatif.” Women’s Writing in the United States. [rest of citation unknown].