Toni Morrison`s “Recitatif”

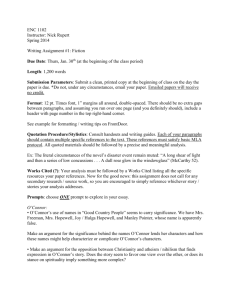

advertisement

Basic Character – an imaginary personage in a literary work who acts, appears, or is referred to in a literary work. › Example? Characterization – the techniques by which an author of a work represents the moral, intellectual and emotional nature of the characters; the art and technique of representing fictional personages which depends upon action or plot as well as narration and point of view. › Example? Major or main characters – those that receive most attention, minor characters receive the least. › Example? Flat characters – are relatively simple, have a few dominant traits, and tend to be predictable. › Example? Round characters – are complex and multifaceted and act in a way that readers might not expect but accept as possible. › Example? Static characters – do not change. › Example? Dynamic characters – do change. › Example? Stock characters – represent familiar types that recur frequently in literary works, especially of a particular genre (e.g., the "mad scientist" of horror fiction and film or the fool in Renaissance, especially Shakespearean, drama). › Specific example? Protagonist – the main character in a work of drama, fiction or narrative poetry › Example? Antagonist – a character or a nonhuman force that opposes or is in conflict with the protagonist. › Example? Foil – a character who contrasts with the protagonist in ways that bring out specific moral, emotional or intellectual qualities in the protagonist (or another character) › Example? Antihero – a protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. › Example? Archetype – a character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). › Example? Born in 1931 in Lorain, Ohio, a steel town on the shores of Lake Erie, Chloe Anthony Wofford was the first member of her family to go to college, graduating from Howard University in 1953 and earning an M.A. from Cornell. She taught at both Texas Southern University and at Howard before becoming an editor at Random House, where she worked for nearly twenty years. In such novels as The Bluest Eye (1969), Sula (1973), Song of Solomon (1977), Beloved (1987), and Paradise (1998), Morrison traces the problems and possibilities faced by black Americans struggling with slavery and its aftermath in the United States. More recent work includes her eighth novel, Love (2003); two picture books for children co-authored with her son, Slade—The Bog Box (1999) and Book of Mean People (2002); a book for young adults, Remember: The Journey to School Integration Toni Morrison on (2004); and What Moves at the Margin: Selected her motivation for Nonfiction (2008). In 1993 she became the first African American author to win the Nobel Prize for writing literature. The word “recitatif” will likely be unfamiliar to you. It is derived from the word “recitative,” which has a number of definitions, all of which hold possible significance for Toni Morrison’s story. The word may refer to a style of expression between song and ordinary speech used by performers during the narrative or dialogue parts of an opera. It also has a now obsolete definition: “the tone or rhythm peculiar to any language.” Recitative may also refer to anything that has the nature of a recital or repetition. Near the end of “Recitatif” the two main characters, Twyla and Roberta, encounter each other while picketing on different sides of a protest related to school busing and school integration. Public schools in the United States were technically desegregated in 1954 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. But, by the 1970s, many American school districts were still segregated in practice because of housing inequalities and because of the ongoing segregation of neighborhoods. In its 1971 ruling on Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of required busing to end school segregation. Under federal court supervision, school districts across the nation in the 1970s and 1980s began assigning students to particular schools based on calculations designed to produce racial balance in those schools, rather than based on the students’ geographic proximity to them. Many families protested and resisted what became known as “forced busing,” claiming that it was burdensome and counterproductive to transport children away from their immediate neighborhoods to attend school. Some children transferred to private schools to avoid compliance with integration reforms. Today, most school districts have ended mandatory busing schemes and de facto segregation continues to exist. (Photo: School Busing protest in the early 1970s) In “Recitatif,” there are five different sections, or “acts,” in which there is an encounter between the narrator, Twyla, and Roberta. In some cases , years separate the encounters. The two characters’ conversations reveal their changing concerns and perspectives, as well as the very different experiences the women have had since the days of their close friendship. For your assigned “act,” please discuss and identify the following: › When does this act take place? Or what is › › › › the approximate ages of the girls/women? What details does the author provide about the race and background of each of the girls? How is each girl characterized in this act? What details are we given? How does that affect our response to each girl/woman? In what way is Maggie a part of this act? Please support your ideas with specific examples from the text! 1. Twyla and Roberta both have mothers who abandon them emotionally but not necessarily physically. How might that affect a young girl’s notion of self-worth? On whom or what would she depend for validation? 2. To what extent, if at all, does Maggie’s race make a difference? 3. Why doesn’t Roberta seem overly bothered by the attack on Maggie and whether she and Twyla only watched or actually participated in the attack? 4. Why do you think Twyla is so deeply affected by Roberta’s stand about busing her children to another school? What does she mean by her placard, “Mothers have rights too!” What does Twyla’s placard, “—And so do children****” mean? 5. When the two women meet in the last episode, Roberta says, “Oh, shit, Twyla. Shit, shit, shit. Well what the hell happened to Maggie?” What does the use of profanity and the sentiment expressed reveal about Roberta’s character?