Recitatif by Tori Morrision

advertisement

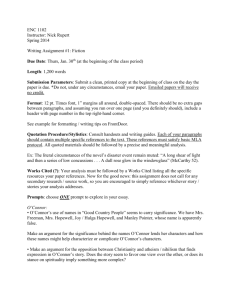

Rachelle Hancock Diversity in Literature Ms. Hull T/TH 1130 February 20, 2012 “She was sandy-colored and she worked in the kitchen” (Morrison 433). This is one of the first introductions to Maggie in the Morrison’s story, Recitiatif. With no defined color, only connected with social class, this sentence really sets the theme in the story. There is a parallel story with the readers and the characters. Throughout the story, Maggie comes up in conversation between Twyla and Roberta, as they decide her race based on their familiarity with racial identity. As we read their story of profiling Maggie’s race, the reader is also profiling the characters race based on their own perceptions of color. We learn from the story that Maggie was mute, she wore a childish hat, and as Twyla remembers her, “ Her legs were like parenthesis, and how she rocked when she walked” (Morrison 433). She is seen as this disabled figure, without a voice, she therefore becomes the perfect target to throw all their repressed hatred for maternal abandonment upon. The reader can come to this conclusion when Twyla explains makes the comparison of her mother to Maggie at the end of the story. She says, “ Maggie was my dancing mother. Deaf, I thought, and dumb. Nobody inside. Nobody who would hear you if you cried in the night. Nobody who could tell you anything important that you could use. Rocking dancing, swaying as she walked” (Morrison 444). Twyla explains she wanted to hurt Maggie, and Roberta agrees when she talks about Maggie when they’re in the coffee shop. Roberta says, “ Listen to me. I really did think she was black. I didn’t make that up. I really thought so. But now I can’t be sure. I just remember her as old, so old. And she couldn’t talk – well, you know, I thought she was crazy. She’d been brought up in an institution like my mother was and like I thought I would be too. And you were right. We didn’t kick her. It was the gar girls. Only them. But, well, I wanted to” (Morrison 445). Here we see in this final conversation, they are discussing the underlining connection with their mothers and Maggie. Although the initial conversation was to discuss the confusion of Maggie’s race. They both seemed to be unsure whether Maggie was white or black. Roberta put a black face on Maggie while Twyla put a white face to her. What does that say about each of the characters? Did they view Maggie as a different race, because she was already physically different from them, so it only made sense in their simple minds to categorize Maggie as different, and put a different face from them on her? Or did they put Maggie in the same race as themselves, and hated her because it was like looking into the face of their mothers? These are interesting questions that the characters could only answer, because it is based on their own structure of racial codes. Which is the point that Morrison tries to convey to the readers through Roberta and Twyla’s story. The point is that there are no racial codes defined by class, nor by referencing a person’s personal experiences. There is a theoretical paradigm that inhibits the readers to conclude race on either characters. Morrison created several points in the story, which were open for interpretation depending on your familiarity with racial identities. To name a few of these phenotypical markers that Morrison gives, she first starts off with the characters names and allows the readers to depict their identity. GoldsteinShirley points out the importance in the names in his literary analysis, Race and Response. He states that the name Roberta, is a feminine version of Robert, which is an old European name, leading some readers to believe Roberta to be white. Mot of these same readers may also depict Twyla as black, in thinking that African Americans give their children nontraditional names. On the other hand, readers who are familiar with the famous African American singer Roberta Flack, could relate that to Roberta Fisk in Morrison’s story. In the story, Roberta marries a man named Kenneth Norton, another well-known name in black history for boxing. So depending on our own diversity and understanding of black and white culture, the reader starts painting on the face of the characters. Morrison delves into connecting race with social status, in the scene with Twyla and Roberta’s mothers. This is a crucial point in the story that starts the readers thinking about how they associate race to class. Twyla’s mother is described as wearing a ratty fur coat and her rear end protruding from her green slacks. Twyla remembers Roberta’s mother as being big. “ Bigger than any man and on her chest was the biggest cross I’d ever seen. I swear it was six inches long each way. And in the crook of her arm was the biggest Bible ever made” (Morrison 435). A White bigot could possibly read into the story that black women are poor and lower class, having a big behind, and Christianity is a form of white European living, not suitable for the black culture. Another reader could possibly read the story as Twyla’s mother being “white trash” and associating Roberta’s mother as a flamboyant southern Baptist, which was common in African American Christianity. Therefore, the reader now is piecing race with these descriptions, although with no hint of color, they are left to their own structured understanding of class and religion to decide the race. Another interesting facet of this story is that the author is left entirely on his own, to interpret the story. Usually the narrator can build trust with the reader, although we see that Twyla even questions her memory and understanding. She says, “ Roberta had messed up my past somehow with that business about Maggie. I wouldn’t forget a thing like that. Would I?” (Morrison 441). We also cannot trust Roberta’s memory because we see that she miss quotes Twyla at the schoolyard. Roberta says, “You kicked a black lady and you have the nerve to call me a bigot” (Morrision 442). We know that nowhere in the text Twyla calls Roberta a Bigot. I think this played a vital roll in the story to have the readers come to their own conclusions, and not taking any one else’s word for it. Recitatif certainly makes readers question their own prejudices and how they categorize race. In the story Roberta and Twyla question their own prejudices, and why they labeled Maggie as white or black; parallel to the reader reflecting on whether they labeled these 2 characters white or black. Therefore we can all learn that race cannot be classified by assumptions from imagination nor experience.