DIVORCE MEDIATION IN EUROPE: An Introductory Outline

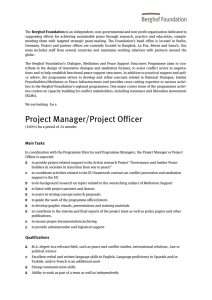

advertisement