natural resources

advertisement

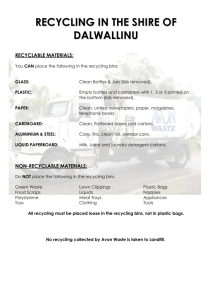

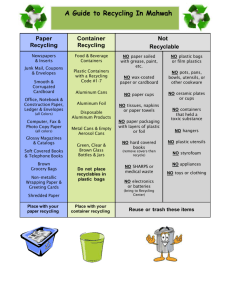

AB 997 Page 1 Date of Hearing: April 13, 2015 ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES Das Williams, Chair AB 997 (Travis Allen) – As Introduced February 26, 2015 SUBJECT: Recycling: plastic material SUMMARY: Revises the state's 75% recycling goal to include waste "used for power generation in dedicated anaerobic digesters as well as in modern landfills capturing methane gas" as recycling. Requires the Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle) to take specified actions to encourage specified waste to energy (WTE) and waste to fuel (WTF) technologies. EXISTING LAW: 1) Establishes the California Integrated Waste Management Act of 1989, which: a) Codifies the state's solid waste hierarchy, which requires that waste management practices be promoted in the following order: i) Source reduction; ii) Recycling and composting; and, iii) Environmentally safe transformation (i.e., WTE) and environmentally safe land disposal, at the discretion of the city or county. b) Specifies a state policy goal that 75% of solid waste generated be diverted from landfill disposal by 2020 through source reduction, recycling, or composting. c) Requires each local jurisdiction to divert 50% of solid waste from landfill disposal. d) Establishes regulatory standards for facilities that convert "engineered municipal solid waste" for energy generation. e) Defines "solid waste" as all putrescible and nonputrescible solid, semisolid, and liquid wastes, including garbage, trash, refuse, paper, rubbish, ashes, industrial wastes, demolition and construction wastes, abandoned vehicles and vehicle parts, discarded home and industrial appliances, non-hazardous sewage, manure, vegetable and animal solid and semisolid wastes, and other discarded solid and semisolid wastes. Specifies that solid waste does not include hazardous waste, radioactive waste, and medical waste. 2) Requires CalRecycle to adopt regulations, as specified, for permitting WTE and WTF facilities that process engineered municipal solid waste (EMSW). Requires that the EMSW replaces or supplants the use of fossil fuels and contains less than 25% moisture and noncombustible waste. AB 997 Page 2 3) Establishes various plastic recycling requirements and incentive programs, including: a) Requires plastic trash bags sold in California to meet specified recycled content requirements and report to CalRecycle. b) Requires rigid plastic packaging containers, as defined, to contain at least 25% postconsumer recycled content, reach specified source reduction requirements, or be reusable. c) Establishes the at-store recycling program for plastic bags, which requires specified stores to collect and recycle plastic bags. d) Specifies that CalRecycle may expend up to a specified amount, currently $10 million, annually for market development payments for empty plastic beverage containers to processors (recyclers) and recycled-content product manufacturers until January 1, 2017. THIS BILL: 1) Revises the state policy goal that 75% of solid waste generated be source reduced, recycled, or composted by the year 2020 to allow solid waste that is "used for power generation in dedicated anaerobic digesters as well as in modern landfills capturing methane gas" to count as recycling. 2) Requires CalRecycle to: a) Investigate emerging technologies that convert used plastic products into "new plastic feedstock and monomers." b) By January 1, 2017, adopt regulations and protocols that encourage WTE and WTF pyrolysis projects that "address various grades of plastic products that are in landfills." c) By January 1, 2017, and annually until January 1, 2020, examine and report to the Legislature on possible incentives for businesses and organizations that practice "state-ofthe-art, cost-effective material separation and recovery techniques, as well as those organizations that are now commercially developing the most cost-effective conversion of mixed plastic, textile, and fiber wastes to fuels." FISCAL EFFECT: Unknown COMMENTS: 1) This bill. According to the author: Plastics exist in far more grades, types, and sub-grades than anyone realizes, and with very few exceptions, for recycled plastics to be used as cost-effective drop-ins for virgin materials requires complete separation from other plastics, other grades of plastics, other product components, contaminants and additives, etc. Separation into the discrete, clean end-useable grades as described above is near-impossible. [Emphasis in original.] AB 997 Page 3 [This bill is intended to] refine and implement those technologies that can derive the maximum value in CA at minimum cost out of the majority of mixed plastics without requiring separation. 2) California's 75% goal. AB 341 (Chesbro), Chapter 476, Statutes of 2011 established a state policy goal that 75% of California's solid waste be diverted from landfill disposal through source reduction, recycling, or composting by 2020. (CalRecycle regulations include anaerobic digestion as composting.) To assist the state in reaching that goal and achieving the state's greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goal to reach 1990 levels by 2020 established by AB 32 (Nunez), Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006, AB 341 included the requirement that commercial generators of solid waste arrange for recycling services. California is currently diverting approximately 65% of solid waste from landfills. AB 341 requires CalRecycle to adopt policies and incentives to significantly increase recycling statewide. Since AB 341 was adopted, CalRecycle launched The 75 Percent Initiative and adopted a statewide strategy to reach the state's recycling goal. Currently, CalRecycle has identified six areas of focus for the initiative: 1) Moving organics out of landfills; 2) Continuing to reform the beverage container recycling program; 3) Expanding the recycling and recycled-content manufacturing infrastructure through streamlined permitting, compliance assistance, and financing incentives; 4) Exploring new models of state and local funding for materials management (for recycling); 5) Promoting state procurement of recycled-content products; and, 6) Promoting expanded producer responsibility. 3) The other 25%. Dwindling landfill capacity and the infeasibility of siting and permitting new disposal sites have created demand for technologies that generate energy and fuels from municipal solid waste. Historically, "WTE" has been used to describe traditional incineration. However, newer technologies, broadly referred to as "conversion technologies," process solid waste through chemical, biological, or other non-combustion thermal technologies to produce electricity or renewable fuels. These technologies create energy using three main processes: thermochemical, biochemical, and physicochemical. Thermochemical conversion processes include high-heat technologies like gasification and pyrolysis. Thermochemical conversion is characterized by higher temperatures and faster conversion rates. It is best suited for lower moisture feedstocks. Thermochemical routes can convert the entire organic portion of suitable feedstocks. The inorganic fraction (ash) does not contribute to the energy products and may contribute to fouling of high temperature equipment and increased nutrient loading in wastewater treatment and disposal facilities. Generally the ash must be disposed. Inorganic constituents may also accelerate some of the conversion reactions. Under current law, pyrolysis is considered transformation, while gasification is explicitly excluded from the definition of transformation. Biochemical conversion processes include aerobic conversion (i.e., composting), anaerobic digestion, which is currently regulated as composting, and anaerobic fermentation (for example, the conversion of sugars from cellulose to ethanol). Biochemical conversion processes use lower temperatures and lower reaction rates. Higher moisture feedstocks are generally good candidates for biochemical processes. The lignin fraction of biomass cannot be converted by anaerobic biochemical means and only very slowly through aerobic decomposition. As a consequence, a significant fraction of woody and some other fibrous AB 997 Page 4 feedstocks exits the process as a residue that may or may not have market value as a soil amendment. The residue can be composted. Physiochemical conversion involves the physical and chemical synthesis of products from feedstocks (for example, biodiesel from waste fats, oils, and grease) and is primarily associated with the transformation of fresh or used vegetable oils, animal fats, greases, tallow, and other suitable feedstocks into liquid fuels or biodiesel. 4) Concerns with conversion. While low-temperature biochemical conversion (i.e., anaerobic digestion and composting of organic materials) have been widely accepted in California and are already considered recycling, higher heat conversion technologies have not been widely accepted as environmentally safe alternatives to landfilling. There have been some pilot and bench scale projects in California and in other parts of the United States, but significant questions remain about the costs, track records, and relevant emissions data from facilities that use feedstocks comparable to California. In response to increasing interest in pursuing WTE options for the remaining 25% of the waste stream and materials that cannot be recycled, AB 1126 (Gordon), Chapter 411, Statutes of 2013 established permitting requirements for conversion facilities that process EMSW, which may include plastic. The CalRecycle process is being developed to ensure that recyclable materials are removed from mixed solid waste prior to being converted for energy or fuels. This bill would require CalRecycle to adopt "regulations and protocols that encourage WTE and WTF pyrolysis projects that address the various grades of plastic products that are in landfills." It is not clear why the bill limits the scope of WTF projects to pyrolysis. This provision is inconsistent with the state's goal of limiting WTE and WTF projects to those that process solid waste from which recyclables have been removed. 5) Managing plastic. Plastic comprises 9.6% of the total disposed waste stream in California. For comparison, organic waste comprises 32.4%, "inert and other" comprises 29.1%, and paper comprises 17.3%. According to the author, "for the majority of plastics, cost-effective recycling is difficult if not impossible." In 2011, the American Chemistry Council released the 2009 National Report on Postconsumer Non-Bottle Rigid Plastic Recycling, which found that between 2007 and 2009, domestic recycling of plastic increased 47%, from 121 million pounds to over 243 million pounds. In 2008 and 2009, North America began recycling more plastic than it exported. According to the report, "non-bottle rigid plastic is sold in a variety of single-resin and mixed-resin categories. The value placed on most mixed-resin bales is dependent on the likely percentage of polyolefin plastics in the bale: higher percentages of polyolefin (polyethylene and polypropylene) generally are in higher demand." Recycling plastic is feasible and does occur on a large scale throughout the United States. 6) Previous legislation. This bill is similar to AB 2633 (Allen), introduced last year; however, AB 2633 did not include the requirement that waste disposed of in a solid waste landfill be counted as recycling if the landfill has a methane capture system. AB 2633 failed passage in this committee on a vote of 3-5. AB 997 Page 5 REGISTERED SUPPORT / OPPOSITION: Support None on file Opposition Californians Against Waste Clean Water Action Coalition for Clean Air Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives Sierra Club California Analysis Prepared by: Elizabeth MacMillan / NAT. RES. / (916) 319-2092