a legal foundation for benefit-cost analysis

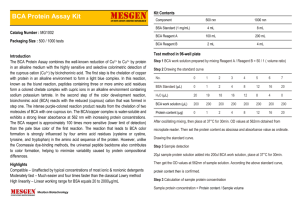

advertisement