Linguistic dimension - Conseil de l`Europe

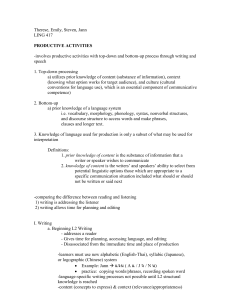

advertisement