Modern at Last? Variety of Weak States in the Post

advertisement

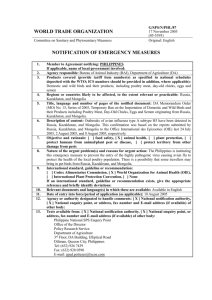

Modern at Last? Variety of Weak States in the Post-Soviet World By Andrei P. Tsygankov In: Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 40, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 423439. Abstract The scholarly interest has recently shifted from issues of democratic transition to those of state formation and state viability. The paper reviews scholarly contributions to understanding state weakness, and suggests criteria and indicators to capture stateness in the former Soviet region. It suggests a preliminary ranking of the post-Soviet states along dimensions of national order, economic efficiency and political viability. The paper hypothesizes a causal mechanism through which a state development in the region may occur by incorporating both structural and policy-related factors. It concludes that most states in the region can only be characterized as weak, and their urge to become modern is therefore yet to materialize. Keywords State-building, weak state, national order, identity, security, political viability, economic viability, post-Soviet world Word count 7,755 1 1. Introduction The scholarly interest has recently shifted to issues of state viability. Academics begun to pay less attention to “regime transition (e.g., from totalitarianism to democracy) in the post-Soviet world than to state formation” (Holloway and Stedman 2002, 170). We are now discovering that weak states have become the central challenge to policy makers concerned with national and international security. In the characterization of two analysts, “failed or dysfunctional states have become breeding grounds for civil wars, genocide and other atrocities, terrorism, famine and the spread of lethal diseases” (Delahunty and Yoo 2007). However, as essential as it is to understand symptoms, causes and spillover effects of state weakness, we are far from developing a strong grasp of these issues. In attempting to contribute to their understanding, this paper suggests an index of state viability and applies it to the nations in the post-Soviet region. It further suggests that most states in the region can only be characterized as weak, which may be viewed as an unfortunate result of their fifteen years transformation. Their urge to become modern is therefore yet to materialize. These findings may only be viewed as preliminary, and qualitative studies must be conducted to confirm or disconfirm hypotheses and results formulated in this paper. To the extend these findings have validity, they suggest significance of policy choices made by state officials. Structural conditions, in which states are to operate – a historical experience with statehood, an endowment with tradable resources or a nature of a geopolitical environment – are also extremely important, but they demonstrate their prominence via specific strategies adopted by policy makers. What matters in statebuilding is a match between structural conditions and state policies. Those states that manage to articulate a policy response creatively building on, rather than ignoring, their structural conditions tend to succeed in solving important economic and political tasks. Alternatively, those that tend to promote policies with no sufficient regard for states’ structural conditions are more likely to fall behind in various dimensions of statehood. A pragmatic, rather than ideological or exclusionary, policy approach therefore remains in high order in the region, and its application deserves to be studied more closely in a future. The paper’s organization is as follows. The next section reviews scholarly contributions to understanding state weakness, and it suggests criteria and indicators to capture stateness for comparative purposes. I then apply these criteria and indicators to the post-Soviet states suggesting their preliminary ranking along several key dimensions. The following two sections discuss in greater details the identified outcomes in weak and viable states, respectively, relating those to policy choices made by their leaderships. Section 6 elaborates on causes of state weakness by incorporating both structural and policy-related factors. It further hypothesizes a causal mechanism through which a state development in the region may occur. The conclusion cautions against interpreting results of the paper as definitive, and it suggests that future changes in leadership and structural environment may challenge our finding. Finally, the paper highlights the importance of policy pragmatism in state building. 2. Criteria and Indicators of Stateness As with any significant change in world politics, transforming the postcommunist region is impossible without involvement of the state. Yet state-building is 2 known to be a historically long and painful process. In Europe, it has gone hand in hand with protracted wars (Tilly 1992) and required negotiating complex deals among kings, merchants and feudal lords (Spruyt 1994). Arguably, the post-Soviet nations face an even more daunting task of creating prerequisites of a viable state, such as territorial unity and security, while transforming economy and political system.1 As some scholars have argued (Bunce 1995), these nations confront the challenge of a “triple transition”: from an empire to a nation, from a command economy to a market-based one, and from a communist to a democratic system. A state can be called viable to the extend it is able to complete the identified “triple transition” toward a national order, an efficient economy and a viable political system. The transition to a national order requires territorial integrity and security from external threats. A new identity of a nation-state is not likely to take roots if a nation remains politically divided or threatened from outside. Creating a viable state is also impossible without an efficient economy which must provide a considerable growth of the national product and population’s higher living standards. Finally, an established national order and a new economy may not last in the absence of a viable political system, of which democracy, as a majority ruly, remains the most effective. A politically viable system is one that successfully articulates social preferences and has an institutional capacity to fight corruption within ruling elite. Political development takes place when transfer of power is seen as legitimate – that is it meets with approval of the public majority – and when it is conducted in peaceful and orderly fashion.2 A stateness as a phenomenon is best thought as a continuum, rather than something given. Conditions of stateness may vary in degree from non-viable to highviable (please see the figure below), and there is now a growing literature on what may constitute failed, weak or viable states (see also Herbst 1990; Clapham 1998; Beissinger and Young 2002; Crocker 2003; Fearon and Laitin 2004; Fukuyama 2004; Krasner 2004; Rotberg, 2003, 2004). In this paper, I will associate a viable state with a considerable progress in meeting the three formulated challenges, and a weak state with lack of such progress. A viable state may still lack some attributes of statehood and therefore qualify as a low-, rather than high-, viable.3 NON-VIABLE Failed Weak VIABLE Low-Viable High-Viable In line with these considerations, I propose several indicators and a general index of stateness. In so doing, I attach equal significance to the three identified challenges. Some might assert that building a state identity is the single most important task without which success of other reforms could not be assured.4 Yet it is also true that in the twenty-first century, national identity is unlikely to be consolidated without an efficient economy and a viable political system. Many scholars also agree that promoting one task of state-building at the expense of another may negatively affect the whole enterprise.5 I acknowledge, of course, that any attempt to propose indicators and construct indices can only be preliminary and suggestive of a general trend. Case studies are necessary to further test how well such indices stand against the empirical record. With these caveats in mind, I propose an index of stateness that would combine indicators of state unity / security, economic and political viability. Each dimension can 3 be estimated on 0 to 1 numerical scale, where 0 stands for no progress, 0.5 some progress and 1 considerable progress. With three equally significant dimensions of stateness captured, stateness will range from 0 to 3. Thus, a state will earn 1 on the unity / security dimension when this state is able to maintain unity of its territory and political class, and when there is no major security threat. The rank of 0 will stand for lack of national unity and security, and 0.5 for a limited progress. A limited progress could imply a nation’s insecurity, yet an internal unity in front of an external threat. On the economic viability, a state will earn the rank of 1 if it has restored or exceeded the size of its economy before the Soviet collapse (1990=100%), and if its absolute poverty rate is below 30% of population. One appropriate definition of absolute poverty was proposed by the World Bank that measures it by the need to live at less than $2.15/day (WB 2005).6 Those states that either have sustained their economy or have relatively low poverty rate – but not both – will earn the 0.5 rank, and those that have none of these two achievements will be ranked as 0. Finally, political viability will be operationalized as legitimate, peaceful and orderly transfer of power over the last ten years that is since 1997, with 1 assigned to those that have experienced such power transfer at least once, 0 to those that have not, and 0.5 to those where power transfer took place with questions regarding its legitimacy, order and peace. The table 1 summarizes results of ranking the former Soviet states, and the next section expands on rationales of arriving at them. [TABLE 1 HERE] 4 3. Stateness in the Post-Soviet World: A Preliminary Record With regard to the unity/security dimension of stateness, the Baltics, Belarus and Kazakhstan show the highest score among the former Soviet states over the fifteen years of their independence. The Baltics and Belarus stayed united and have experienced virtually no threat to their security from outside. Kazakhstan too remained united despite the potential for ethnic Russian mobilization in the northern part of the country. Relative to other states in the Central Asia and the Caucasus, Kazakhstan has experienced few security threats although it has felt some effects of the region’s drug trade and terrorism (Pala 2002; Cornell and Swanstrom 2006). On the other extreme, are those states that have failed to achieve territorial integrity and to provide security for its citizens. Azerbaijan, Georgia and Moldova all have developed acute issues of secessionism. Having passed the stage of active military confrontation, they have made little progress in bringing secessionist territories under control and continue to live in a shadow of war. Most states show a mixed unity/security record and therefore fall in the intermediate category. Armenia has no territorial integrity problem, but its citizens live under a constant fear of war with Azerbaijan. The latter has drastically increased its military budget and on many occasions threatened to use force to persuade Armenia to give up its support for Nagorno-Karabakh’s secessionism (Giragosian 2006). Tajikistan has re-established its territorial unity after a civil war in the 1990s, but, as a neighbor of Afghanistan, the country has fallen a victim of the drug trade and has been the most directly affected by the drug-related criminal infiltration (Cornell and Swanstrom 2006, 21; see also Engvall 2006). Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan did not go through a devastating civil war, but have also been seriously affected by the drug trade. Russia and Uzbekistan have preserved territorial integrity, but at an extremely high cost of military and civilian casualties. Both countries continue to suffer from activities of terrorist networks on their territories. Finally, Ukraine’s problem is that of deeply divided political elite. Although the country has been in no major danger of terrorism or narcotic trafficking, it continues to experience serious risks to territorial integrity. The historically pronounced regional divisions (Wilson 1998, 2000; Molchanov 2002) – with the east favoring stronger ties with Russia and the west eager to minimize those ties – have been threatening unity of the ruling elite. Table 2 summarizes the post-Soviet states’ unity/security record. [TABLE 2 HERE] A different picture emerges on the dimension of economic efficiency (for a summary of the post-Soviet states ranking on this dimension, please, see table 3 below). Most successful states are Azerbaijan, the Baltics, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Each of them has fully revived its economy exceeding the 1990 level considerably.7 As of 2006, their GDP have constituted 128% (Azerbaijan), 121% (the Baltics8), 132% (Belarus) and 122% (Kazakhstan). Russia is only entering this group, having surpassed the 1990 level in GDP terms as of January 2007 (Pankov 2007). In addition to the effective economic performance, all the five nations managed to keep their absolute poverty level below 30%, with the figures of 6% (Azerbaijan), 5% (the Baltics), 3% (Belarus), 27% (Kazakhstan) and 10% (Russia). Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova and Tajikistan, on the other hand, have neither revived their economies, nor brought the absolute poverty to the sufficiently low level. With GDP of 59% (Georgia), 84% (Kyrgyzstan), 49% (Moldova) and 78% (Tajikistan), 5 relative to 1990, and the poverty level of 59% (Georgia), 80% (Kyrgyzstan), 62% (Moldova) and 81% (Tajikistan) of the overall population, they have remained the weakest in the post-Soviet region. Four states - Armenia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Ukraine – are in the middle group. The first three have recovered or exceeded their GDP level of 1990, yet they have not made much progress in fighting poverty. Ukraine’s problem is just the reverse: its absolute poverty level is 4% - much lower than in the rest of the group – yet its GDP level remains mere 58% of its 1990 level. [TABLE 3 HERE] In terms of political viability, the most viable states seem to be Lithuania, Moldova and Russia where transfer of power took place at least once since 1997 and resulted from popular and competitive elections. Although many observers have criticized examples of what they saw as non-democratic practices in application to these countries, particularly Russia,9 few have challenged the legitimacy and orderly nature of their power transition. On the other extreme are the countries, where transfer of power was illegitimate or did not take place altogether. Armenia and Azerbaijan are examples of illegitimate power transitions. In case of the former, Robert Kocharyan replaced Levon Ter-Petrosyan in what observers perceived to have been a palace coup,10 while the latter experienced a pattern of dynastic power change with Aliyev-son “inheriting” the official leadership from his farther. In Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, leaders stayed in the office, and the transfer of power did not take place. In the middle group are two Baltic states, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine. In case of Estonia and Latvia, one can speak of a partly legitimate power transfer given that a large part of sizable ethnic Russian minorities does not participate in national elections. Some scholars referred to the system as “ethno-democracy” (Roeder 1994; Smith 1998). In Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine power was transferred as a result of revolutions with questions regarding order, legitimacy and viability of the post-revolutionary political system. Table 4 summarizes the post-Soviet states’ political viability record. [TABLE 4 HERE] 4. Variety of Weak States Therefore nine, or most of the states in the post-Soviet region can be classified as weak with the score of stateness ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 (see table 1). Policies pursued by their leadership are partly responsible for this outcome. As diverse as they have been, such state policies have been marked by similar disregard for their societies’ structural conditions, among which are ethnic heterogeneity, weak national identity, lack of internationally tradable resources and volatile geopolitical environment. Rather than giving their due to these conditions, state leaders pursued various types of exclusionary policies, as opposed to those of pragmatic or more inclusive nature. This section reviews different types of exclusionary policies as partly responsible for state weakness, while the next one looks closer at viable states and pragmatic policies pursued by their leaders. The states of the Caucasus and Moldova pursued ethnically exclusionary policies in a multiethnic context thereby generating hostilities and complicating the process of state-building. In the late-1980s – early 1990s, these societies went through devastating wars from which they have not fully recovered. Violence in Azerbaijan toward its 6 residents of Armenian nationality took place in response to secessionist claims of Nagorno-Karabakh and reached the proportion of ethnic cleansing. Armenia’s reaction has been, predictably, of ethnonationalist nature as well, and the two nations’ conflict has been the subject of scholarly attention (Dawisha and Parrott 1997; Rubin and Snyder 1998; Bertsch 2000; Ebel and Menon 2000; Alaolmolki 2001; Gadziyev 2001; Miller and Miller 2003). Georgia and Moldova have developed largely along the same lines. In Georgia, its first leader Zviad Gamsakhurdia took away status of autonomy from provinces of diverse ethnic origins, and his ethnically chauvinistic attitude provoked South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Adjaria to take up arms against Tbilisi (Goodman 1997; Gadziyev 2001). In Moldova, some ethnonationalists within the political leadership favored integration with the neighboring Romania, which pushed the area of the proRussian Transdnistria away (Bennett 1999; 312-313; Tuminez 2000, 247; Holloway and Stedman 2002, 179). In all cases, ethnonationalist policies have been responsible for mass migrations, economic hardship and, ultimately, inability to create a viable statehood. State disintegration has gone so far that in estimates of some scholars, it is no longer a question of secessionism or “frozen conflicts”, but that of a de facto state-building by non-recognized autonomies (King 2001). Uzbekistan pursued a similar policy of ethnic exclusiveness directing it against other independent states in the region, rather than its own provinces. Widely recognized as aspiring to hegemony in the Central Asia (Birgerson 2002, 151-153), President Islam Karimov targeted sizable community of ethnic Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan basing his imperialist policies on various glorifying myths. The ethno-imperialist mindset is revealed in Karimov’s (1998) book, in which he traces the origins of his nation to the Soviet Turkestan or “Turan” that once combined most of Central Asia, as well as to the fourteenth century Mongol ruler Tamerlane. In addition to intimidating Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Uzbekistan’s policies caused concerns regarding regional security and balance of power among larger states in the region, especially Kazakhstan and Russia. At home, ethno-imperialism was accompanied by persistent military build-up and oppression of liberally-minded opposition preparing the ground for moving toward a less politically viable state. An additional obstacle to state-building in the Central Asia has been clanexclusive policies of its leaders. In case of Tajikistan, a clan confrontation led to a civil war (Dadmehr 2003, 250; Holloway and Stedman 2002, 179). In Kygyzstan, clans infighting, along with President Askar Akayev’s preferences for his own southern clan (Collins 2004, 241), contributed to a popular uprising in March 2005. In Uzbekistan, some members of rival clans that had not been sufficiently rewarded by Karimov, launched a vendetta against the president provoking him to adopt more authoritarian policies. Threats to government reached unprecedented levels in 2004. A series of suicide bombings took place at the main bazaar in Tashkent and foreign embassies (Miller 2006, 67-68). In each of these cases, the central leadership was unable either to avoid clan pressures or to alleviate those pressures through allocation of available resources (Collins 2004). Ukraine has been an example of state practicing regionally exclusionary policies. Rather than trying to bridge their regional divide by preserving relations with Russia, the early Ukrainian state attempted to break centuries-old ties with the Eastern neighbor.11 The support for the second president Leonid Kuchma came predominantly from the 7 eastern part of the country. The nation’s linguistic and historical divisions run deep, and any attempts by central authorities to prioritize interests of one region at the expense of another are likely to encourage political instability and economic stagnation.12 The Orange revolution’s difficulties to put Ukraine on a path of national unity and sustainable economic development seem to support this conclusion. Finally, Turkmenistan has built a system that is best described as sultanist. German political economist Max Weber defined Sultanism as an extreme form of patrimonialism, when an administration and military force "are purely personal instruments of the master" and domination "operates primarily on the basis of discretion" (quoted in Linz and Stepan 2006, 177). Sultanism combines traditional domination with a cult of personality and is especially prone to corruption. Unlike the Middle Eastern petrostates that are heavily influenced by networks of royal-family ties, clans and oligarchies, Turkmenistan's ruler minimized the role of clans and special-interest groups. Niyazov's ruling system integrated a rich supply of energy resources with the former Soviet structure of power, and – because of energy needs by all major nations in the region – it remained practically invulnerable to external pressures. A country that has been as wealthy on a per capita basis in its natural resources as Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan has wasted most of its opportunities and now bears no comparison to its Caspian neighbor in almost any dimension of state viability. In addition to dismal socio-economic indicators, one-third to one-half of the population under 30 years old are drug addicts, partly because of enormous heroin traffic from neighboring Afghanistan and Iran and partly because of the regime's own encouragement of opium users (Lebedev 2002). Table 5 provides a summary of policies that have led to state weakness in the former Soviet region. [TABLE 5 HERE] 5. Six Viable States The relative success of the viable states can be partially traced to their pragmatic policy stances. In contrast to the described exclusionary policies, pragmatism is more inclusive and may be defined as a policy of exploiting available resources and structural conditions in the interests of a larger society. Pragmatism is a variable and does not necessarily mean a comprehensive inclusion of all relevant social groups’ interests. Still, it is assumed here that under a condition of a threat, a pragmatic policy maker will be more inclined to make a deal with a rival than exclude or isolate him. Six states qualify as viable, with the stateness score ranging from 2 to 3. Rather than pursuing a single-minded policy, such as neoliberal shock therapy or state socialism, these states adopted approaches that were more appropriate for their structural conditions. The Baltic states chose a model of dependence on Western European nations in order to provide themselves with security and economic prosperity. Having suffered through a radical neoliberal transformation, the Baltics have sharply diversified their trade patterns away from the former Soviet region and toward the European Union. This strategy has proven a success, as they have become members in the EU and NATO. Belarus pursued a radically different approach of becoming a client state of Russia. Over fifteen years after the Soviet disintegration, it has further increased its economic and political dependence on Russia. By some calculations, Russia subsidized up to 40% of the neighbor’s budget (Dzhadan 2007), and the strategy has been successful in bringing Belarus the sought 8 security and economic viability. Indeed, Belarus record of unity/security and economic viability has been far more impressive than that of Russia itself. Kazakhstan’s model can be defined as that of a neopatrimonial independence. While remaining patrimonial, Kazakhstan has not evolved into a Turkmenistan-like Sultanist regime that would satisfy the interests of a narrow minority at the expense of the larger society. Kazakhstan has launched important economic and educational reforms, preserved inter-ethnic balance and stimulated immigration to the country (Pala 2002; Hill 2005). Kazakh elites have agreed to settle their differences in complex, if hidden, negotiations, and they have not sought to overthrow the authority of the largest clan associated with President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The formal authority of the leader has gone unchallenged in exchange for Nazarbayev’s honoring acquired social privileges of the elites. Internationally, the state managed to maintain balanced relations with Russia, the EU, the United States and China attracting the largest amount of foreign investments to the country. Kazakhstan’s natural resources contributed to these successes, yet it was the pragmatic state policy that diversified the economy and prevented the country from becoming an energy-dependent petrostate. Finally, Russia’s case is that of a post-imperial independence. Russia has been less successful than other viable states in the region arguably because it has originally pursued the policy of dependence on the West. Its economic and political indicators have suffered partly because it has tried to be Baltics, while having a different set of structural conditions of a formerly imperial power with abundant natural resources and a long tradition of a strong state involvement in social life. It was only a matter of time for Russia to realize its comparative advantage. Throughout the 1990s, the country has created necessary macroeconomic environment and abstained from attempts to restore its empire. Although it almost had become a failed state (Holmes 1997; Stavrakis 2002, 264; Meierhenrich 2004, 154; Popov 2004; Willerton, Beznosov and Carrier 2005) in response to its original shock therapy choice, it has revived its economy and a good measure of political viability under leadership of Vladimir Putin. In Russia’s case, pragmatism meant integrating the previously excluded security elites in the ruling class and concentrating on building a “normal great power” (Tsygankov 2005) – not by means of imperial grandeur, but through reformed macroeconomic conditions, favorable world energy prices, and stable political environment for economic growth and rising living standards.13 Table 6 summarizes pragmatic policy choices in the former Soviet region. [TABLE 6 HERE] 6. Key Explanatory Factors Any discussion of stateness must go beyond policy choices and consider roles played by structural conditions. A part of the answer to the question why some leaders choose a pragmatic approach, while others do not, depends on policy makers’ individual characteristics and social environment. Yet the other part of the answer has to do with structural conditions in which state leaders act. This section highlights five structural explanations of state weakness. It also sketches a causal process that links structural factors and outcomes in stateness. The first structural condition to consider is a historical experience with statehood a nation had before it has became politically independent. It is this experience that fosters the overall commitment to state among its citizens thereby creating the sense of national 9 identity.14 Those with stronger national identity are in a better position to overcome the dominance of tribal, clan, or ethnic affiliations and to establish a viable state than those that never had any state experience. Although most former Soviet states cannot boast a considerable historical experience with statehood, the Baltics have been independent during the interwar years and preserved a sense of national identity even while being a part of the Soviet empire. This sense has assisted them in preserving external identification with the world of European nation-states, and it has shaped their drive to integrate with European economic and security institutions (Tsygankov 2001). However, a quarter-century experience with independence, the Baltics had, was not sufficient from entirely preventing them from adopting exclusionary policies in the post-Soviet state building. Haunted by some painful Soviet memories Latvia and Estonia made it difficult for their sizable Russian minorities to be politically integrated in the Baltic societies. The experience of other states is even less encouraging. Ethno-nationalism of the states in the Caucasus has proven to be the dominant force, and it has been championed by Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Abulfaz Elchibei, and Robert Kocharyan, among other state leaders. The states of Central Asia, with the possible exception of Kazakhstan, remain predominantly affected by clan affiliations (Collins 2004). The second condition is retained Russia’s economic assistance after the Soviet disintegration. Russia has been slow to withdraw its energy subsidies for the former Soviet states, and all of them have taken advantage of it. Transit states, such as Baltics, Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus, also profited handsomely by reselling considerable portions of Russian supplies to European consumers at world market price.15 Yet Russia’s assistance has been a variable, and some have been more dependent on it than others. Those with greater political loyalty to Russia, such as Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, have received much greater share of assistance than those aspiring to join alternative economic and political organizations. Still another critical factor is the newly independent states’ geopolitical location and proximity to sources of instability, terrorism, and drug trade. The geopolitical environment has been more favorable for the Baltics, Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus and less favorable for the states of the Caucasus. It has been the least favorable for the Central Asia, given this region’s proximity to highly unstable and Afghanistan and Pakistan. No less important has been a competition among established and emerging great powers, such as Russia, the United States, Turkey, China, Iran and the European Union, for resources and political domination in the region. Enormous energy reserves and the volatile geopolitical environments place the region at the center of large powers’ calculations. The American analyst Zbigniew Brzezinski has been perhaps more frank than others in advising the United States to win support of Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan as “pivotal” states in the region (Brzezinski 1997), but other great powers too have been eager to expand their influence after the breakup of the Soviet state. For smaller states trying to improve their viability, this competition has been of questionable value. In the absence of explicit rules of competition among great powers, the “pivotal” states have often been subject of rival pressures with dramatic consequences for their own stability. Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine and most of the Central Asia have been especially affected. Finally, those with internationally tradable resources, particularly oil and natural gas, has been in a more advantageous position to become viable states, others being equal. 10 Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have all been richly endowed with natural resources, and that provided their governments with greater flexibility in choosing a path to statehood. The process through which structural conditions affect state viability outcomes is summarized in table 7. The earlier discussed policy choice is an intervening variable of a principal significance; without state policy – exclusionary or pragmatic – it is impossible to determine the role played by structural factors. Some brief comparisons may assist us in further highlighting the significance of governmental policy. States may, despite similarity in structural conditions, arrive at very different outcomes in viability. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, for example, have been richly endowed with natural resources, and yet arrived at very different results. It is policy choices that assist us in explaining why Kazakhstan has been a viable state with a diversified economy, while Turkmenistan has been a weak state that continues to fall behind in indicators of stateness. States lacking natural resources may also perform differently. A comparison of Belarus and Kyrgyzstan too suggests a prominence of policy choices. While Belarus oriented its economy toward Russia and pursued egalitarian social policies, Kyrgyz ex-president Askar Akayev championed neoliberal reform agenda and, later, concentrated most of the power resources in hands of one clan. Such policies contributed to undermining economic and political foundations of Kyrgyzstan’s statehood. Finally, a comparison of Uzbekistan and Russia might be instructive. Both possess large reserves of natural resources, and both have experienced serious terrorist threats to their statehood. A partial reason why Russia’s state has gotten stronger has to do with the pragmatic choice to concentrate on rebuilding the economy, rather than restoring the imperial power. concentrate on rebuilding the economy, rather than restoring the imperial power. On the other hand, Uzbekistan’s problems can be attributed – along with lack of statehood experience – to president Karimov’s ethno-imperialist claims that have been nothing but diversion from a path toward a successful state building. [TABLE 7 HERE] 7. Conclusions The paper has established, in a preliminary fashion, that the post-Soviet region has made a modest progress in state-building. Only six states – the Baltics, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia – can be recognized as viable; the other nine remain, for various reasons, weak and therefore potentially dangerous to their citizens and the outside world. Moreover, the fact that the six states have reached a certain degree of viability does not mean that such state of affairs is irreversible. Belarus, for instance, remains deeply vulnerable as a client state of Russia. With Russia changing its approach to energy subsidies, Belarus is likely to become the first to suffer, particularly if it shows limited flexibility regarding its patron’s demands. Alternatively, some currently weak states may find additional resources and political will for lifting themselves out of their political and economic weakness. It must therefore be acknowledged that our results are applicable only to first fifteen years of the post-Soviet transformation. If, however, the first fifteen years are of significance, they suggest prominence of policy choices adopted by states in the beginning of their existence. In some cases, as Kalevi Holsti wrote in a different context, “the colonial state, an organism that left legacies primarily of arbitrary boundaries, bureaucracy, and the military, was taken over 11 by leaders who believed they could go on to create real nations and master the new state” (Holloway and Stedman 2002, 170). Yet exclusionary choices rarely, if ever, have paid off. Without policy pragmatism, defined as ability to match actions with specific structural conditions, the region is likely to continue to show a dismal record in state viability. 12 Table 1. Stateness in the Post-Soviet World: Criteria and Indicators* Armenia Azerbaijan Baltics Belarus Georgia Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Moldova Russia Tajikistan Turkmen-n Ukraine Uzbekistan (1) (2) (3) Overall Score 0.5 0 1 1 0 1 0.5 0 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0.5 0.5 0.5 0 0 0.5 0 0.5 0 0.5 1 1 0 0 0.5 0 1 1 2.5-3** 2 0.5 2 1 1 2.5 0.5 1 1.5 1 * All indicators are based on 0 to 1 scale, with possible score of stateness (SS) ranging from 0 to 3. ** Estonia and Latvia score 2.5, whereas Lithuania scores 3 due to their differences with regard to ethnic restrictions on citizenship and elections (please see table 4) (1) Unity / Security: estimate of preservation of national and territorial unity and security from external threats. (2) Economic Viability: cumulative economic growth change since 1990 (1990=100%) and the absolute poverty rate, with “poor” defined as having over 30% of population living at less than $2.15/day. (3) Political Viability: peaceful, orderly and legitimate transfer(s) of power over the last ten years (since 1997). Sources: Grigoryev and Salikhov 2006; Pankov 2007; WB Growth, Poverty, and Inequality 2005; the author’s estimates; RFE/RL RR; JRL 13 Table 2. Post-Soviet States: Record of Unity / Security Rank State Record 1 Baltics, Belarus Unity / no threats Kazakhstan Unity / some terrorism threat Armenia Unity / war threat Tajikistan Relative unity after civil war / narcotics threat Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan Relative unity / narcotics threat Russia, Uzbekistan Relative unity / terrorism threat Ukraine Divided elite / no threats Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova No territorial unity / low security 0.5 0 14 Table 3. Post-Soviet States: Record of Economic Efficiency Rank State Record 1 Azerbaijan, Baltics, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia Economy above 1990 level / poverty below 30% 0.5 Armenia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan Economy above 1990 level / poverty above 30% Ukraine Economy below 1990 level / poverty below 30% Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan Economy below 1990 level / poverty above 30% 0 15 Table 4. Post-Soviet States: Record of Political Viability Rank State Record 1 Lithuania, Moldova, Russia Legitimate, peaceful and orderly power transfer 0.5 Estonia, Latvia Partly legitimate power transfer: ethnic restrictions on citizenship and elections Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine Power transfer by revolution with questions regarding its legitimacy, peace and order Armenia, Azerbaijan Illegitimate power transfer: coup or family network Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan No transfer of power 0 16 Table 5. Weak Post-Soviet States: Policy Choices Policy Choice State Ethno-nationalism Caucasus, Moldova Ethno-imperialism Uzbekistan Clan-exclusionary policy Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan Region-exclusionary policy Ukraine Sultanism Turkmenistan 17 Table 6. Viable Post-Soviet States: Policy Choices Policy Choice State West-dependence Baltics Russia-dependence Belarus Neopatrimonial independence Kazakhstan Post-imperial independence Russia 18 Table 7. Structural Factors and Stateness: The Causal Process Structural Factors Exclusionary Weak State Pragmatic Viable State State Policy 19 References Alaolmolki, Nozar. 2001. Life after the Soviet Union. The Newly Independent Republics of the Transcaucasus and Central Asia. New York: SUNY Press. 320 pp. Beissinger, Mark R. and Crawford Young, eds. 2002. Beyond State Crisis? Postcolonial Africa and Post-Soviet Eurasia in Comparative Perspective. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. Bennett, Andrew. 1999. Condemned to Repetition? The Rise, Fall and Reprise of SovietRussian Military Interventionism, 1973-1996. Cambridge: The MIT Press. Bremmer, Ian. 2006. The J Curve: A New Way to Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall. New York: Simon & Shuster. Bertsch, Gary K. et al., eds. 2000. Crossroads and Conflict. Security and Foreign Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia. London: Routledge. Birgerson, Susan M. 2002. After the Breakup of a Multi-Ethnic Empire. New York: Praeger. Blum, Douglas. 2003. Contested national identities and weak state structures in Eurasia. In: Limiting institutions? The Challenge of Eurasian security and governance, edited by James Sperling, Sean Kay and S. Victor Papacosma. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Brzezinski, Zbigniew. 1997. The Grand Chessboard. New York: Basic Books. Bunce, Valerie. 1995. Should Transitologists Be Grounded? Slavic Review 54 Clapham, Christopher. 1998. Degrees of Statehood. Review of International Studies 24. Collins, Kathleen. 2004. The Logic of Clan Politics: Evidence from the Central Asian Trajectories. World Politics 56, January. Cornell, Svante E. and Niklas L. P. Swanstrom. 2006. Eurasian Drug Trade: A Challenge to Regional Security. Problems of Post-Communism 53, 4. Crocker, Chestera A. 2003. Engaging Failing States. Foreign Affairs 82, 5. Dadmehr, Nasrin. 2003. Tajikistan: Regionalism and Weakness. In: State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror, edited by Robert L. Rotberg. Cambridge: World Peace Foundation / Brookings Institution Press. Dawisha, Karen and Bruce Perrott, eds. 1997. Conflict, cleavage, and change in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Delahunty, Robert and John Yoo. 2007. Lines in the Sand. National Interest, Vol. 87, Jan/Feb. Dzhadan, Igor’. 2007. Belorusski motiv. Russki zhurnal, January 17. Ebel, Robert and Rajan Menon, eds. 2000. Energy and Conflict in Central Asia and Caucasus. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Engvall, Johan. 2006. The State Under the Siege: The Drug Trade and Organized Crime in Tajikistan. Europe-Asia Studies 58, 6. Fearon, James and David Laitin. 2004. Neotrusteeship and the Problem of Weak States. International Security 28, 4. Frye, Timothy. 2002. The Perils of Polarization: Economic Performance in the Postcommunist World. World Politics 54, April Fukuyama, Francis. 2004. State-building: governance and world order in the 21st century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Gadziyev, Kamaludin S. 2001. Geopolitika Kavkaza. Moskva: Mezhdunarodniye otnosheniya. 20 Ganev, Venelin I. 2005. Postcommunism as an episode of state-building: a reversed Tillyan perspective. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38. Grigoryev, L. M. and M. P. Salikhov. 2006. Virazhy perekhodnogo perioda. Rossiya v global’noi politike No. 6, November-December available at: http://www.globalaffairs.ru/numbers/23/6691.html Giragosian, Richard, “Military Buildup in South Cacausus Adds to Tensions,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, October 16, 2006, available online at <http://www.rferl.org/newsline/5-not.asp> Herbst, Jeffrey. 1990. War and State in Africa. International Security 14, 4. Hill, Fiona. 2005. Whither Kazakhstan? Parts I-II. National Interest, September, October. Holmes, Stephen. 1997. What Russia Teaches Us Now: How Weak States Threaten Freedom. The American Prospect, No. 33, July-August. Holloway, David and Stephen John Stedman. 2002. Civil Wars and State Building in Africa and Eurasia. In: Beyond State Crisis? Postcolonial Africa and Post-Soviet Eurasia in Comparative Perspective, edited by Mark R. Beissinger and Crawford Young. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. Huntington, Samuel. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press. Huntington, Samuel. 1991. The Third Wave. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. JRL. Johnson Russia List. Karimov, Islam. 1998. Uzbekistan on the Threashold of the Twenty-First Century. New York: St. Martin’s Press. King, Charles. 2001. The Benefits of Ethnic War: Understanding Eurasia's Unrecognized States. World Politics 53, July. Krasner, Stephen D. 2004. Sharing Sovereignty: New Institutions for Collapsed and Failing States. International Security 29, 2. Kuromiya, Hiroaki. 2005. Political Leadership and Ukrainian Nationalism, 1938-1989. Problems of Post-Communism 52, 1. Lebedev, Gennadi. 2002. Turmenski tranzit. Novaya gazeta, April 11. Linz, Juan and Alfred Stepan. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. Linz, Juan J. and Alfred Stepan. 2006. Modern Nondemocratic Regimes. In: Essential Readings in Comparative Politics, edited by Patrick H. O’Neil and Ronald Rogowski. New York: W. W. Norton, 2nd edition. MacFarlane, Neil S. 1997. Democratization, Nationalism, and Regional Security in the Southern Caucasus. Government and Opposition. № 10. McFaul, Michael. 2002. The Fourth Wave of Democracy and Dictatorship: Noncooperative Transitions in the Postcommunist World. World Politics 54, 2. Meierhenrich, Jens. 2004. Forming States after Failure. In: When States Fail: Causes and Consequences, edited by Robert L. Rotberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Miller, Eric A. 2006. To Balance or Not to Balance: Alignment Theory and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London: Ashgate. Melville, A. Yu., M. V. Ilyin, Ye. Yu. Meleshkina, M. G. Mironyuk, I. N. Polunin and Timofeyev 2006. Opyt klassifikatsiyi stran. Polis, No. 5. Miller, D. E. and L. T. Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. Berkeley: UC Press, 2003. 21 Molchanov, Mikhail. 2002. Political Culture and National Identity in Russian-Ukranian Relations. Austin: Texas University Press. Pala, Christopher. 2002. The Jewel of Central Asian Republics. Insight on the News 18, March 11. Pankov, Georgy. 2007. Russia lacks public optimism for an economic leap. RIA Novosti, February 6. Popov, Vladimir. 2004. The State in the New Russia (1992-2004): From Collapse to Gradual Revival? PONARS Policy Memo 324 <http://www.csis.org/ruseura/ponars> RFE/RL RR. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Report. Roeder, Philip. 1994. Variety of Post-Soviet Authoritarian Regimes. Post-Soviet Affairs 10, 1. Rotberg, Robert I., ed. 2003. State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror. Cambridge: World Peace Foundation / Brookings Institution Press. Rotberg, Robert I., ed. 2004. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Rubin, B. and J. Snyder, ed. 1998. Post-Soviet Political Order. Conflict and StateBuilding. London: Routledge. Smith, Graham. 1998. Post-Soviet States: Mapping the Politics of Transition. Oxford: Arnold. Smolansky, Oles M. 1999. Ukraine’s Economic Dependence on Russia. Problems of Post-Communism 46, 2. Spruyt, Hendrik. 1994. Sovereign State and Its Competitors. Princeton University Press. Stavrakis, Peter J. 2002. The East Goes South: International Aid and the Production of Convergence in Africa and Eurasia. In: Beyond State Crisis? Postcolonial Africa and Post-Soviet Eurasia in Comparative Perspective, edited by Mark R. Beissinger and Crawford Young. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion, Capital and European States AD 992-1990. Blackwell: Cambridge. Tsygankov, Andrei P. 2001. Pathways after Empire: National Identity and Foreign Economic Policy in the Post-Soviet World. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Tsygankov, Andrei P. 2005. Vladimir Putin’s Vision of Russia as a Normal Great Power. Post-Soviet Affairs 21, 2. Tuminez, Astrid S. 2000. Russian Nationalism Since 1856: Ideology and the Making of Foreign Policy. Lanham, MD: Rawman & Littlefield. WB 2005. Growth, Poverty, and Inequality. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Willerton, John P., Mikhail Beznosov, and Martin Carrier. 2005. Addressing the Challenges of Russia’s “Failing State”. Demokratizatsiya 13, 2. Wilson, Andrew. 1998. Ukrainian nationalism in the 1990s. A minority faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wilson, Andrew. 2000. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. New Haven: Yale University Press. 22 Endnotes 1 Venelin Ganev (2005) suggested comparing dilemmas of postcommunist state weakness with – following Tilly – those of early modern European state formation. 2 I emphasize the notion of power transfer, rather than democracy, because my main preoccupation is with the overall result of institutional performance, rather than institutions themselves. In addition, scholars continue to disagree on what counts as institutional preconditions of democracy with some focusing on elections as the single most important condition (Huntington 1991), while others advocating a far more elaborate list of conditions (Linz and Stepan 1996). In emphasizing institutional perfomance, I am also reminded by Samuel Huntington’s (1968) observation, “communist totalitarian states and Western liberal states both belong generally in the category of effective rather than debile political systems.” 3 In this regard some analysts use the notion of a strong state which is close to the meaning of my concept of high-viable state. Robert Rotberg (2003, 4) defines strong states as those that “unquestionably control their territories and deliver a full range and a high quality of political goods to their citizens.” Another scholar differentiates between primary and secondary institutions of the state suggesting the concept of the “usable state.” Usable states do not necessarily deliver democracy or high living standards, yet they are likely to serve the following functions: (1) encouraging predictability; (2) creating confidence; (3) lending credibility; (4) providing security; (5) desplaying resolve; and (6) controlling resources (Meierhenrich 2004, 156). 4 For instance, Jens Meierhenrich’s (2004) argument about the importance of primary institutions comes close to making this argument. 23 5 For example, some have argued against universality of economic and political openness for advancing a rapid economic growth (Bremmer 2006). Others emphasized importance of political unity in economic transition (Frye in WP). Still others have been engaged in what remains a largely unresolved debate on roles played by agency, process and sequence of policies versus structural conditions during a transition from authoritarian rule (For a good summary of the debate, see Linz and Stepan 1996). 6 It is important to note limitations of quantitative data and agencies that collect them. To their credit, the World Bank and other agencies gathering economic data in the former Soviet space are quite open about reliability and historical comparability of the data. 7 For data sources, please see sources to table 1. 8 Average for the three Baltic states here and elsewhere. 9 For example, in its 2006 report the Freedom House (www.freedomhouse.org) have rated Russia as “Not Free” on the ground of suppressing civil liberties. 10 See, for example, McFaul 2002. The coup was preceeded by the ban of the largest opposition movement (Dashnaks) and manipulations of 1995 and 1996 elections (MacFarlane 1997). 11 For different interpretations of the policy, see Smolansky 1999 and Tsygankov 2001, 90-92. 12 For a recent argument about significance of historical and geopolitical constraints on Ukrainian leaders, see Kuromiya 2005. 13 The ratings developed by Russian analysts differ from those of Western agencies, such as Freedom House and Fund for Peace, considerably. (For details, please, 24 see these organizations’ websites at www.freedomhouse.org and www.fundforpeace.org). One example of is publication of “Geopolitical Atlas of Contemporary World” (Melville, Ilyin, Meleshkina, Mironyuk, Polunin and Timofeyev 2006). While recognizing the constraining role of various threats on Russia’s development, Russian analysts assign for their country relatively high ratings of “stateness” and “international influence.” Unlike the Freedom House, they also classify Russia as a democracy, albeit an imperfect one, which may invite scholars to re-evaluate meaning of the concept in Russia’s conditions. 14 For an argument about a state capacity as linked to a consolidated national identity, see Blum 2003. 15 Russia also provided various military assistance, which in some cases – Tajikistan being one (Dadmehr 2003, 257) – proved crucial for negotiating peace among warring parties. 25