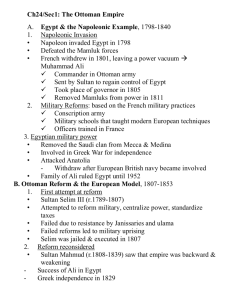

The Ottomans are one of the greatest and most powerful civilizations

advertisement

The Yellow Parts are necessary!!!!

The Ottomans are one of the greatest and most powerful civilizations of the modern period. Their moment of glory

in the sixteenth century represents one of the heights of human creativity, optimism, and artistry. The empire they

built was the largest and most influential of the Muslim empires of the modern period, and their culture and military

expansion crossed over into Europe. Not since the expansion of Islam into Spain in the eighth century had Islam

seemed poised to establish a European presence as it did in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Like that earlier

expansion, the Ottomans established an empire over European territory and established Islamic traditions and culture

that last to the current day (the Muslims in Bosnia are the last descendants of the Ottoman presence in Europe).

The Ottoman empire lasted until the twentieth century. While historians like to talk about empires in terms of

growth and decline, the Ottomans were a force to be reckoned with, militarily and culturally, right up until the

break-up of the empire in the first decades of this century. The real end to the Ottoman culture came with the

secularization of Turkey after World War II along European models of government. The transition to a secular state

was not an easy one and its repercussions are still being felt in Turkish society today; nevertheless, secularization

represents the real break with the Ottoman tradition and heritage.

We will start with the greatest figure of Ottoman history, the Sultan Suleyman, who built from the conquests of his

father a great city, military machine, empire, and culture. No culture seems to invite such a total association of the

entire history and greatness of the culture in a single individual as Ottoman culture does. This is not just a European

prejudice; Muslims themselves can hardly resist the temptation of summing up the whole of Ottoman culture and

history in this brilliant and dignified human being. For very few figures in history encompassed so much of their

culture, and very few near-mythical figures have left so much of their humanity to posterity. For Islam produces an

odd relationship between individuals and history. The inherent dignity and perfectibility of humanity in Islam tends

to produce mythical figures like Suleyman who seem to master every human art; but the spiritual egalitarianism of

the religion also leads to a surprising humanisation of these mythical figures.

The Ottoman State

The Ottomans inherited a rich mixture of political traditions from vastly disparate ethnic groups: Turks, Persians,

Mongols, Mesopotamian and, of course, Islam. The Ottoman state, like the Turkish, Mongol, and Mesopotamian

states rested on a principle of absolute authority in the monarch. The nature of Ottoman autocracy, however, is

greatly misunderstood and misinterpreted in the West, particularly in world history textbooks.

The central function of the ruler or Sultan in Ottoman political theory was to guarantee justice ('adala in Arabic)

in the land. All authority hinges on the ruler's personal commitment to justice. This idea has both Turco-Persian and

Islamic aspects. In Islamic political theory, the model of the just ruler was Solomon in the Hebrew histories

(Suleyman is named after Solomon). The justice represented by the Solomonic ruler is a distributive justice; this is a

justice of fairness and equity that comes closer to the Western notion of justice. In addition, however, 'adale has

Turco-Persian coordinates; in this tradition, 'adale, or justice, is the protection of the helpless from the rapacity of

corrupt and predatory government. In this sense, justice involves protecting the lowest members of society, the

peasantry, from unfair taxation, corrupt magistracy, and inequitable courts. This, in Ottoman political theory, was

the primary task of the Sultan. He personally protected his people from the excesses of government, such as

predatory taxation and the corruption of local officials. For the Ottomans, the ruler could only guarantee this justice

if he had absolute power. For if he was not an absolute ruler, that meant that he would be dependent on others and so

subject to corruption. Absolute authority, then, was at the service of building a just government and laws rather than

elevating the ruler above the law as Europeans have interpreted the Sultanate.

In order to ensure 'adale, the Ottomans set up a number of practices and institutions in the central government

surrounding the Sultan. The first was the establishment of a bureaucracy drawn from the Sultan's inner circle. This

bureaucracy in turn controlled local governments; this would become the model of European absolutism in the

seventeenth century. Other institutions and political practices were:

Observance of government: The Sultan's job was primarily to keep a watch on all the officials. In some cases, this

observance of government involved the personal involvement of the Sultan. He would sometimes observe in secret

the proceedings of the Diwan, which was the central advisory group to the sultan, and sometimes observe

proceedings of ulamacourts. Periodically, the Sultan was required to tour local governments in disguise to ensure

that magistrates and justices were operating justly. If the Sultan believed that an injustice was being committed

against the people, he would interfere directly and overturn the decision. Islamic historians argue that the Ottoman

Empire decline primarily because later Sultans took less and less interest in maintaining justice in their Empire. For

the most part, however, the Sultan monitored local officials through a vast, complex, and elaborate system of spies

who would report back to the central bureaucracy. The intelligence gathering system in the Ottoman Empire was the

best in the world until the twentieth century.

Siyasa: Rooting out corruption meant nothing if nothing was done about it. Public agents and officials that abused

their power and the peasantry were subjected to a special jurisdiction called the siyasa. The siyasawere a set of

severe punishments imposed by the Sultan on corrupt officials; there was no way out, no cash compensation could

take the place of the corporeal or, more often, capital punishments swiftly and severely meted out to corrupt

officials. In the siyasasystem, the most severe crimes involved illegal taxation or forced labor of the peasantry,

staying in their homes without permission or billetting troops without permission, and requiring peasants against

their will to provide food for them or for soldiers. Such crimes almost certainly meant the death penalty.

Public declaration of laws and taxes: In order to prevent fraudulent taxes and arbitrary laws by public officials, the

Sultanic "orders" (firman) and taxes were declared and posted in public. There was, then, always direct

dissemination of central government to the people directly.

Accessibility : Perhaps the most important aspect of Ottoman centralized government was universal access to

centralized authority. The highest reaches of power—with the exception of the person of the Sultan—was available

to each and every citizen of the Empire. Every single member of Ottoman society could approach the Imperial

Council with grievances against government officials; these official petitions were called ard-imahdarand were

always treated with the utmost seriousness. If the Imperial Council ruled against the officials, they would often be

subjected to the siyasa.

Public opinion: The most common misconception about Islamic rulers in general and Ottoman rulers in particular

was that they were removed, aloof, and uninterested in their people. While this may be physically true, it was not

ideologically true. In fact, in the Ottoman state, public opinion was regarded as the only true foundation on which

state authority rested. If the people ceased to support their rulers, it was argued, then the rulers would soon fall from

power. The Sultanic government, then, assiduously cultivated public opinion, for it was recognized that the enemies

of the Sultan were also cultivating adverse public opinion. The government did this not only through propaganda,

but through policy as well. In addition to prosecuting corrupt government officials and publicly declaring taxes and

laws, the Ottoman government also cultivated public opinion in its wars of conquests. Soldiers were not allowed to

mistreat peasants nor take anything from them without their permission or reimbursement. All the Ottoman wars of

the conquest in the sixteenth century were assiduously planned years in advance. The government would lay up

stores of supplies all along the campaign route so that the armies could feed themselves without taking anything

from the general population. The Ottoman conquerors believed that no conquest could stand without the goodwill of

the general population of the conquered, so military campaigns were remarkably fair and easy on the average

person.

The Structure of Government

Officially, the Sultan was the government. He enjoyed absolute power and, in theory at least, was personally

involved in every governmental decision. In the Ottoman experience of government, everything representing the

state government issued from the hands of the Sultan himself.

The Sultan also assumed the title of Caliph, or supreme temporal leader, of Islam. The Ottomans claimed this title

for several reaons: the two major holy sites, Mecca and Medina, were part of the Empire, and the primary goal of the

government was the security of Muslims around the world, particularly the security of the Islamic pilgrimage to

Mecca. As Caliph, the Sultan was responsible for Islamic orthodoxy. Almost all of the military conquests and

annexations of other countries were done for one of two reasons: to guarantee the safe passage of Muslims to Mecca

(the justification for invading non-Muslim territories) and the rooting out of heterodox or heretical Islamic practices

and beliefs (the justification for invading or annexing Muslim territories).

Historians simply can't agree on how the Sultanate was passed from generation to generation among the Ottomans.

In the early history of the Empire, the Sultanate clearly passes from father to eldest son; in 1603, at the death of

Ahmed I (1603-1617), the Sultanate passed to the brother of the Sultan. Still, the Ottomans did not seem to have a

hereditary system based on primogeniture (crown passes to the eldest son) or seniority (crown passes to the next

oldest brother). In both Turkish and Mongol monarchical systems, the passing of the crown is a haphazard affair.

Both the Turkish and Mongol peoples believed that the crown fell to the most worthy inheritor. Each individual in

the hereditary line, brothers and sons, were equally entitled to the crown. This meant that successions were almost

always major struggles among contending parties. The Ottomans seem to have operated in a similar system. When a

Sultan passed away, the crown, it was believed, fell to the most worthy successor (almost always the eldest

son).Selim I had to fight for the Sultanate, but Suleyman was the only son of Selim and so inherited the crown

without a struggle. Once a Sultan had assumed the throne, all his brothers were executed as well as all their sons—

had SelimI lost his bid for the crown, Suleyman would have been killed. These executions guaranteed that there

would be no future wars or struggles between claimants to the throne since all the contenders but one were out of the

picture.

In the seventeenth century, Ottoman Sultans began to revise this practice and simply imprisoned their brothers—

this is what permitted Ahmed I to be succeeded by his brother. Western historians point to this practice as one of the

central reasons why the Sultanic government failed. Since the crown was falling to individuals that had been

imprisoned much if not most of their lives, the Ottoman state saw a succession of mad Sultans and the

corresponding increase in power of a corrupt bureaucracy.

The fundamental qualification for the Sultanate was the individual's worthiness to fill the position. The Ottomans

believed that simple succession proved that the Sultan was worthy of the crown; however, the Sultan may grow old,

feeble, or corrupt and thus lose his worthiness to serve as Sultan. Selim I came to the throne by deposing his old

father, Bayezid II (1481-1512), who was too old to lead the army against external threats. When Suleyman had

become an old man, his two sons, Bayezid and Mustafa, his favorite son, plotted to overthrow him. Faced with this

treason, the old Suleyman had to execute them both and this seems to have broken his spirit completely.

Although the Sultan was regarded as personally responsible for every government decision, in reality the

government was run by a large bureaucracy. This bureaucracy was controlled by a rigid and complex set of rules,

and the Sultan himself was constrained by these rules. At the top of the bureaucracy was the Diwan("couch"), which

served as a cabinet to the Sultan for making decisions. The most powerful member of the Sultan's government was

the Grand Vizier who largely oversaw all the executive functions of the government. Appointments to these

positions were not arbitrary but followed strict rules.

Suleyman the Conqueror

Suleyman believed that the entire world was his possession as a gift of God. Even though he did not occupy Roman

lands, he still claimed them as his own and almost launched an invasion of Rome (the city came within a few

hairbreadths of Ottoman invasion in Suleyman's expedition against Corfu). In Europe, he conquered Rhodes, a large

part of Greece, Hungary, and a major part of the Austrian Empire. His campaign against the Austrians took him

right to the doorway of Vienna.

Besides invasions and campaigns, Suleyman was a major player in the politics of Europe. He pursued an

aggressive policy of European destabilization; in particular, he wanted to destabilize both the Roman Catholic

church and the Holy Roman Empire. When European Christianity split Europe into Catholic and Protestant states,

Suleyman poured financial support into Protestant countries in order to guarantee that Europe remain religiously and

politically destabilized and so ripe for an invasion. Several historians, in fact, have argued that Protestantism would

never have succeeded except for the financial support of the Ottoman Empire.

Suleyman was responding to an aggressively expanding Europe. Like most other non-Europeans, Suleyman fully

understood the consequences of European expansion and saw Europe as the principle threat to Islam. The Islamic

world was beginning to shrink under this expansion. Portugal had invaded several Muslim cities in eastern Africa in

order to dominate trade with India, and Russians, which the Ottomans regarded as European, were pushing central

Asians south when the Russian expansion began in the sixteenth century. So in addition to invading and

destabilizing Europe, Suleyman pursued a policy of helping any Muslim country threatened by European expansion.

It was this role that gave Suleyman the right, in the eyes of the Ottomans, to declare himself as supreme Caliph of

Islam. He was the only one successfully protecting Islam from the unbelievers and, as the protector of Islam,

deserved to be the ruler of Islam.

While the expansion of European power helps explain Suleyman's conquest of European territories, it doesn't help

us when it comes to the vast amount of Islamic territory that he invaded or simply annexed. How does conquering

Islamic territory "protect" Islam? The Ottomans understood this as belonging to Suleyman's task as universal Caliph

of Islam. This role demanded that Suleyman also see to the integrity of the faith itself and to root out heresy and

heterodoxy. His annexation of Islamic territory, such as the annexation of Arabia, were justified by asserting that the

ruling dynasties had abandoned orthodox belief or practice. Each of these invasions or annexations were preceded,

however, by a religious judgement by Islamic scholars as to the orthodoxy of the ruling dynasty.

Suleyman the Builder

Suleyman undertook to make Istanbul the center of Islamic civilization. He began a series of building projects,

including bridges, mosques, and palaces, that rivalled the greatest building projects of the world in that century. The

greatest and most brilliant architect of human history was in his employ: Sinan. The mosques built by Sinan are

considered the greatest architectural triumphs of Islam and possibly the world. They are more than just aweinspiring; they represent a unique genius in dealing with nearly insurmountable engineering problems.

Under Suleyman, Istanbul became the center of visual art, music, writing, and philosophy in the Islamic world.

This cultural flowering during the reign of Suleyman represents the most creative period in Ottoman history; almost

all the cultural forms that we associate with the Ottomans date from this time.

The reign of Suleyman, however, is generally regarded, by both Islamic and Western historians, as the high point

of Ottoman culture and history. While Ottoman culture flourishes during the reign of Selim II, Suleyman's son, the

power of the state, internally and externally, began to perceptibly decline. Islamic historians believe that the decline

was due to two factors: the decreased vigilance of the Sultan over the functions of government and their consequent

corruption, and the decreased interest of the government in popular opinion. Western historians are not sure how to

explain the decline after the death of Suleyman. A major factor seems to be a series of eccentric and sometimes

insane Sultans all through the seventeenth century. When the Ottomans abandoned the practice of killing all rivals to

the throne, they began to imprison them. The Sultanate, then, often fell to individuals who had been imprisoned for

decades and, well, there was often no cream filling in those Twinkies. This led to the growth of the power of the

bureaucracy and its consequent corruption (this does not fundamentally disagree with the Islamic version of

Ottoman history).

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman Empire was still the most powerful state in the world both

in wealth and military capability. The personal style of government, however, cultivated among the earlier Sultans

had gone away completely. In place of Sultanic government, the bureaucracy pretty much ran the show. Power

struggles among the various elements of the bureaucracy: the grand vizier, the Diwan, or supreme court, and

especially the military, the Janissaries, led to a constant shifting of government power. Islamic historians point out

that the growth of bureaucratic power and the disinterest of the Sultans led to corrupt and predatory local

government which eroded popular support. Western historians point to internal decline in the bureaucracy along

with increased military efficiency of European powers as the principle reason for the decline of the Empire.

However it may be, the decline of the Ottomans was a staggered affair lasting over two centuries. The Empire itself

would exist until World War I, at which point it was finally erased from the maps by European powers.

Perhaps the most significant innovation in Sultanic government was the preservation of the brothers of the Sultan.

In the late sixteenth century, the Ottoman Sultans abandoned this practice, yet still distrusted filial loyalty. So the

brothers of the Sultan were locked away in the harem in the palace. While they lived in luxury, they were still forced

to live in small rooms and often in isolated conditions. Many of them went mad, but most simply became fat and

lazy, addicted to alcohol and food and lying about. All of them made bad Sultans, completely disengaged from the

government. In addition, the Sultans abandoned the practice of training their sons to assume the Sultanate by having

them serve in the government and the military. In both Islamic and Western histories of the Ottomans, this decline in

the Sultanate is regarded as one of the prime causes of its decline.

As a result of the disintegration of the instituion of the Sultanate, power had to go somewhere. It principally went

to the Janissaries, the military arm of the government. Throughout the seventeenth, the Janissaries slowly took over

the military and administrative posts in the government and passed these offices on to their sons, mainly by bribing

officials. Because of this practice, Ottoman government soon began to be ruled by a military feudal class. Under the

early Ottomans, position in the government was determined solely through merit. After the sixteenth century,

position in government was largely determined by hereditary. The quality of the administration and bureaucracy

declined precipitiously.

The process of the Sultan's disengagement with government actually began with Suleiyman. Towards the end of his

life, weary, tired, and broken by the executions of his two favorite sons, Suleyman withdrew into his great Topkapi

palace and handed the reigns of government over to his Grand Vizier. This was the model that his son would follow.

In addition, however, Suleiyman abandoned with his son Selim a tradition among the Ottoman Sultans: raising his

child to become Sultan. The sons of the Sultan were expected to participate in government and military training and

campaigns; only this period of apprenticeship would make them worthy of the Sultanate. Suleiyman had done this

with his older children, particularly Mustafa. But Mustafa and Bayezid betrayed him. Selim, then, lived a very

isolated existence in the harem of Topkapi palace. He was not trained in government or military affairs, so there was

little reason for him to take any interest in them.

Selim II reigned for only eight years, but he set the precedent for Ottoman rule for the next two centuries and the

great Empire, the great Caliphate that stood as a lion before the advancing mercantile and military expansion against

Europe, slowly crumbled under European pressure.

Muhammad Kuprili

The most significant figure among the Ottomans of the seventeenth century was Muhammad Kuprili (1570-1661),

who, as Grand Vizier, halted the general decline of Ottoman government by rooting out corruption all through the

imperial government and returned to the old Ottoman practice of closely observing local government and rooting out

injustice. He also tried to revive the Ottoman practice of conquest and protecting Muslim countries from European

expansion. Although it didn't happen in his lifetime, this new expansionist policy would begin the steady stream of

military defeats against European powers that would slowly contract the Empire.

Wars with Austria

Shortly after Muhammad Kuprili died, his brother-in-law, Kara Mustafa, took over the military and put into

practice Kuprili's new expanionist policies. His first target was the Hapsburg Empire of Austria. He wanted nothing

less than the complete conquest of Austria, so he marched straight for the capital, Vienna. In 1683, with Vienna

under siege, the Ottomans were defeated by an alliance of European forces and by the heavy artillery that had come

into practice among European armies. While this defeat initiated a long period peace in the relationships between the

Ottomans and the Europeans, it also effectively ended the Ottoman wars of conquest, and the end of conquest also

began the steady deterioration of Ottoman power over European territories.

In 1699, the Ottomans signed the Peace of Karlowitz. In this treaty, the Ottomans handed over to Austria the

provinces of Hungary and Transylvania, leaving only Macedonia and the Balkans under Ottoman control, but the

Balkans had begun to destabilize after the Ottoman defeat of 1683.

European Wars

In the eighteenth century, the Ottomans fought a series of wars with European powers. Between 1714 and 1718,

they fought with the small country of Venice; between 1736 and 1739, they fought with Austria and Russia in order

to stop the expansion of these powers into Muslim territories. The Russians in particular continued to aggressively

expand their state into Muslim territories in Central Asia; these small Muslim states had no place to turn to except

the Ottomans. War with Russia, in fact, dominates the Ottoman scene from much of the eighteenth century; the two

states clashed between 1768 and 1774, and again between 1787 and 1792. In all these wars of the eighteenth

century, there were no clear victors or losers.

Internal Decline

European historians tend to present Ottoman decline solely from the perspective of the wars with Europe. While

these wars were significant, Ottoman decline was more pronounced internally and economically in the eighteenth

century. There are two overwhelming aspects of this decline: meteoric population increase and the refusal to

modernize.

For all that we say about Ottoman decline, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were periods of relative

prosperity. As a result, however, the population of the Empire doubled .This eventually produced endemic

unemployment and famine when the economic resources of the country could not support such a large population.

The wealth of the Ottomans was largely due to their presence on trade routes. The Empire stood astride the

crossroads of all the continents and sub-continents: Africa, Asia, India, and Europe. However, European expansion

created new trade routes that bypassed Ottoman territories. Vast amounts of revenue began to disappear from the

economy. Because the state collected tariffs on all good passing through the Empire, the imperial government itself

lost vast amounts of its revenue.

In addition, the Ottomans did not industrialize in the way Europeans were doing in the eighteenth century. Remember:

industrialization isn't mechanization . It principally involves a complete overhaul of labor practices. The Ottomans retained old

labor practices, in which production was concentrated among craft guilds. Increasingly, the economic relationships between the

Ottomans and the Europeans shifted gears. Europeans increasingly bought only raw materials from the Ottomans, and then

shipped back finished products manufactured in Europe. Since these finished products were produced with new, industrial

methods, they were far cheaper than similar products produced in Ottoman territories. This practice effectively destroyed the

Ottoman craft industries in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.