How DNA Computers Will Work

advertisement

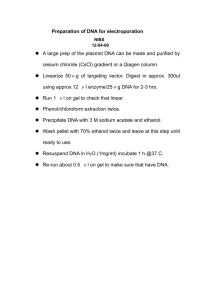

How DNA Computers Will Work DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) molecules, the material our genes are made of, have the potential to perform calculations many times faster than the world's most powerful human-built computers. DNA might one day be integrated into a computer chip to create a so-called biochip that will push computers even faster. DNA molecules have already been harnessed to perform complex mathematical problems. In 1994, Leonard Adleman introduced the idea of using DNA to solve complex mathematical problems. Adleman, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California, came to the conclusion that DNA had computational potential after reading the book "Molecular Biology of the Gene," written by James Watson, who co-discovered the structure of DNA in 1953. In fact, DNA is very similar to a computer hard drive in how it stores permanent information about your genes. Adleman is often called the inventor of DNA computers. His article in a 1994 issue of the journal Science outlined how to use DNA to solve a well-known mathematical problem, called the directed Hamilton Path problem, also known as the "traveling salesman" problem. The goal of the problem is to find the shortest route between a number of cities, going through each city only once. As you add more cities to the problem, the problem becomes more difficult. Adleman chose to find the shortest route between seven cities. Here are the steps taken in the Adleman DNA computer experiment using his DNA test-tube computer: Strands of DNA represent the seven cities. In genes, genetic coding is represented by the letters A, T, C and G. Some sequence of these four letters represented each city and possible flight path. These molecules are then mixed in a test tube, with some of these DNA strands sticking together. A chain of these strands represents a possible answer. Within a few seconds, all of the possible combinations of DNA strands, which represent answers, are created in the test tube. Adleman eliminates the wrong molecules through chemical reactions, which leaves behind only the flight paths that connect all seven cities. The success of the Adleman DNA computer proves that DNA can be used to calculate complex mathematical problems. However, this early DNA computer is far from challenging silicon-based computers in terms of speed. The Adleman DNA computer created a group of possible answers very quickly, but it took days for Adleman to narrow down the possibilities. Another drawback of his DNA computer is that it requires human assistance. The goal of the DNA computing field is to create a device that can work independent of human involvement. Tube test with details We create test tubes that have many multiples of the strands representing each edge and each vertex. Once these tubes are mixed together, legal paths through the graph are generated by the mutual attraction of strings and their complements by hydrogen bonding. For example, take the graph shown in figure . Since this example has six vertices and the DNA alphabet only contains the letters A, T, C, and G, it is necessary to have each vertex represented by at least two characters. We expand this to eight characters in order to avoid the problem of long common sub-strings, and denote each vertex by a DNA strand as listed in table . The edges, furthermore, are represented as in table . Vertex DNA Strand Edge DNA Strand A ATCGAGCT A -> B TCGAACCT B TGGACTAC B -> C GATGCTCT C GAGACCAG C -> D GGTCGCTA D CGATGCAT D -> F CGTACGAT E AGCTAGCT F -> E CTGATCGA F GCTAGACT E -> F TCGACGAT E -> A TCGATAGC E -> B TCGAACCT B -> F GATGCGAT We can now see that, given this representation, strands representing vertex A in a test tube will tend to pair with strands representing edges of the form A -> x. Because of this tendency to pair, one can construct all paths through the graph by simply producing large quantities of each of the strands listed in table and mixing them together. Other environmental conditions must be met so that the pairing process takes place as intended, but those details will be left for later discussions. Once all of the legal paths are constructed, finding a solution (if one exists) to the instance of HP is equivalent to finding a double-stranded DNA sequence that contains exactly one copy of the strands representing each vertex. This search can be performed using methods from molecular biology. Moreover, each of steps (including the synthesis of the paths) could be performed in linear time and thus the entire algorithm can be executed in linear time. To Adleman, the following advantages of DNA computing became evident; Speed – Conventional computers can perform approximately 100 MIPS (millions of instruction per second). Combining DNA strands as demonstrated by Adleman, made computations equivalent to 10 9 or better, arguably over 100 times faster than the fastest computer. [5] The inherent parallelism of DNA computing was staggering. Minimal Storage Requirements – DNA stores memory at a density of about 1 bit per cubic nanometer where conventional storage media requires 1012 cubic nanometers to store 1 bit. [5] In essence, mankinds collective knowledge could theoretically be stored in a small bucket of DNA solution. Minimal Power Requirements - There is no power required for DNA computing while the computation is taking place. The chemical bonds that are the building blocks of DNA happen without any outside power source. There is no comparison to the power requirements of conventional computers. There have been other researchers since Adlemans work that have demonstrated similar possibilities of DNA computing. For example a group of researchers at Princeton in early 2000 demonstrated an RNA computer similar to Adleman’s which had the ability to solve a chess problem involving how many ways there are to place knights on a chess board so that none can take the others. Adleman instantly envisioned the use of DNA computing for any type of computational problems that require massive amounts of parallel computing. As his background stemmed from computer encryption, he particularly envisioned DNA computing in helping create and decipher algorithms in the field of cryptography. The possibility existed of the very genetic makeup of an individual being used in the encryption/decryption of data from/to that person. The possibility was also seen that the DNA of an individual will give them the ‘who you are’ portion of the ‘who you are’, ‘what you know’, ‘what you have’ aspects of security authentication. There has been much speculation of the use of this type of technology for cryptographic and steganographic means that would take advantage of the parallel computation possibilities available with DNA computing. Are these real possibilities for the security industry or are the processes involved in its implementation too difficult to envision in the immediate future? Next we will examine DNA computing within these security applications to determine the likelihood of DNA being used in their advancement.