Pulmonary Atresia

advertisement

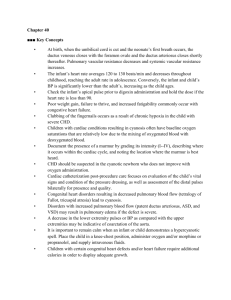

Pulmonary Atresia source: Children’s Heart Federation Animation available at: http://www.childrens-heartfed.com/resources__and__info/heart_conditions/pulmonary_atresia Pulmonary Atresia What is pulmonary atresia? Pulmonary atresia (PA) is a complicated congenital (present at birth) defect that occurs when the pulmonary valve, located between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery, is not formed properly. The pulmonary valve has three leaflets that function like a one-way door, allowing blood to flow forward into the pulmonary artery, but not backward into the right ventricle. With pulmonary atresia, problems with valve development prevent the leaflets from opening; therefore, blood cannot flow forward from the right ventricle to the lungs. Before birth, while the fetus is developing, this is not a threat to life, because the placenta provides oxygen for the baby, and the lungs are not functional. Blood entering the right side of the fetal heart passes through an opening called the foramen ovale, which allows oxygen-rich (red) blood to pass through to the left side of the heart and proceed to the body. In some cases, there may be a second opening, this time in the ventricular wall, that allows blood in the right ventricle a way out. This opening is called a ventricular septal defect (VSD). If there is no VSD, the right ventricle receives little blood flow before birth and does not develop fully. After birth, the placenta no longer provides oxygen for the newborn -- the lungs must provide it. With no pulmonary valve opening present, however, blood must find another route to reach the lungs and receive oxygen The foramen ovale normally shuts at birth, but may stay open in this situation, allowing oxygen-poor (blue) blood to pass from the right atrium to the left atrium. From there, it goes to the left ventricle, out the aorta, to the body. This situation cannot support life, since oxygen-poor (blue) blood cannot meet the body's demands. Newborns also have a connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, called the ductus arteriosus, that allows some of the oxygen-poor (blue) blood to pass into the lungs. Unfortunately, this ductus arteriosus normally closes within a few hours or days after birth. Because of the low amount of oxygen provided to the body, pulmonary atresia is a heart problem that is labeled "blue-baby syndrome." Pulmonary atresia occurs in about one out of every 10,000 live births. What causes pulmonary atresia? Pulmonary atresia occurs due to the improper development of the heart during the first eight weeks of fetal growth. Some congenital heart defects may have a genetic link, either occurring due to a defect in a gene, a chromosome abnormality or environmental exposure, causing heart problems to occur more often in certain families. Most of the time, this heart defect occurs sporadically (by chance), with no clear reason for its development. What are the symptoms of pulmonary atresia? Symptoms will be noted shortly after birth. The obvious indication of PA is a newborn who becomes cyanotic (blue) in the transitional first day of life, when the maternal 2 source of oxygen (from the placenta) is removed. The degree of cyanosis is related to the presence of other defects that allow blood to mix, including a patent ductus arteriosus. The following are the most common symptoms of pulmonary atresia. Each child, however, may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include: rapid breathing difficulty breathing irritability lethargy pale, cool or clammy skin What are the treatments for pulmonary atresia? Specific treatment for pulmonary atresia will be determined by your child's physician based on: your child's age, overall health and medical history extent of the disease your child's tolerance for specific medications, procedures or therapies how your child's doctor expects the disease will progress your opinion or preference Your child most likely will be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or special care nursery once symptoms are noted. Initially, your child may be placed on oxygen, and possibly on a ventilator, to assist his/her breathing. Intravenous (IV) medications may be given to help the heart and lungs function more efficiently. Other important aspects of initial treatment include the following: A cardiac catheterization procedure can be used as a diagnostic procedure, as well as an initial treatment procedure, for some heart defects. A cardiac catheterization procedure will usually be performed to evaluate the defect(s), whether the foramen ovale or ductus arteriosus are still open, and the amount of blood that is mixing. As part of the cardiac catheterization, a procedure called balloon atrial septostomy may be performed to improve mixing of oxygen-rich (red) blood and oxygen-poor (blue) blood between the right and left atria. An intravenous medication called prostaglandin E1 is given to keep the ductus arteriosus from closing. These interventions will allow time for your baby to stabilize. Ultimately, surgery is necessary to improve blood flow to the lungs on a permanent basis. A series of operations are usually recommended and are performed in stages, usually starting shortly after birth. In this series of operations, blood flow is redirected to the lungs and the body with various surgical connections. The surgical correction of pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum depends on the degree of underdevelopment (hypoplasia of the tricuspid valve and right ventricle). When hypoplasia is mild, the blocked pulmonary valve can sometimes be 3 opened in the catheterization laboratory. More commonly, however, it is necessary to undertake a surgical procedure with placement of a patch to enlarge the outflow part of the right ventricle and the valve area. Generally, the patch is constructed using the child's own natural tissue from around the heart (pericardium). What is the long-term outlook after pulmonary atresia surgical repair? The outlook varies from child to child. Follow-up care at a center at a center offering pediatric congenital cardiac care should be carried out regularly. It is not unexpected for multiple re-operations to be performed to replace conduits or revise a palliation. After each operation, your infant will need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist who will make adjustments to medications, assist you with feeding problems, measure oxygen levels, and determine when it is time for the next operation. There is significant risk for progressive development of complications such as heart failure, dysrhythmias, and protein-losing enteropathy (liver congestion). Pregnancy and other non-cardiac surgeries pose major risks and require careful evaluation and discussion with a congenital cardiologist. Regular follow-up care at a center offering pediatric or adult congenital cardiac care should continue throughout the individual's lifespan. Source: Children’s Hospital, Boston Cardiology Website, Accessible at: http://www.childrenshospital.org/az/Site509/mainpageS509P0.html 4