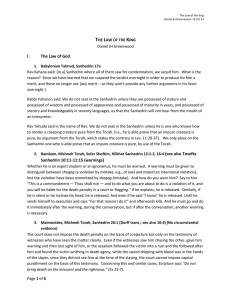

One of the most popular forms of execution in ancient times

advertisement

Of pain, dignity and death by Shammai Engelmayer One of the most popular forms of execution in ancient times was crucifixion. The Carthaginians used it; so did the Persians and their ilk (mainly the Seleucids in Assyria). The Romans made heavy use of it to put down insurrections. Titus, when in command of the siege of Jerusalem, is reported by Josephus to have crucified 500 Jews a day throughout the threeyear siege. The Hasmonean monarch Alexander Jannai reportedly had as many as 800 Pharisees killed this way. Whether anyone was ever nailed to a cross is the subject of debate, even though one body was recovered with a nail through the victim’s heel. (This one body may actually prove that nailing was not common, because there were tens of thousands of victims, but only one set of remains that says otherwise.) An Israeli anthropologist, Joe Zias, notes that the body’s weight combined with the softness of human flesh would probably cause the person to fall off the cross within 10 minutes, obviously with hands and feet ripped to shreds. Besides, nailing a person to a cross would hasten death and that would have defeated the purpose, which was to cause a lingering and excruciating death, topped off by a heavy dose of extreme humiliation, both ante- and post-mortem. A person was tied to a cross in such a way as to make his limbs stretch painfully as birds of prey picked away at his body. Death often took three days or more to mercifully arrive. Then the body would be left to rot for several more days. Finally, whatever was left was taken down and tossed away for the animals to pick over. No crucifixions were known before the 5th century B.C.E. Prior to that (and even long after crucifixion ceased being the execution method of choice), people would be speared through, then nailed to a wall or a wooden post to be exhibited and picked over. Most often, the head would be removed and placed separately for all to see. There were other horrific methods of execution, and all shared the two most necessary components: extreme pain and abject humiliation. Two very distinctly different recent events raise the question of whether we actually have come very far in the intervening millennia. One is a Supreme Court decision in a death penalty case. The other is the aftermath of the death of Abu Musab al Zarqawi. What ties these two cases together is that they each have one element of the old ways. In the Supreme Court case, that element is undue pain. In the case of al Zarqawi, his death probably was painless, even though he lingered for 72 minutes after the bombing raid that caused his fatal wounds, so extensive were his internal injuries. Whether he actually knew what hit him is also in doubt. Unlike the ancient methods, his body was not nailed to a wall. In a very real sense, however, his head was “cut off” and put on display—on the front pages of newspapers around the world and beamed to the four corners by satellite television. Even as I write this, several days after his death, his body has not been buried, as far as is known. In the Supreme Court case, Hill v. McDonough, an unusually unanimous opinion made it easier for condemned felons to argue that the lethal injection method of execution amounts to cruel and unusual punishment. At issue was a specific chemical used in the death-inducing cocktail; most of the states that use the drug ban its use for euthanizing animals precisely because it does cause painful deaths. Allowing the argument to be made, however, is not the same as banning the method. The court would not go that far, at least not yet. Obviously, the 25 states and the Bush administration that argued in favor of the cocktail are less concerned about the pain as they are about bringing about the condemned’s death. Jewish law—going back to the Torah itself—is very clear on both the pain and humiliation questions. Regarding humiliation, the Torah states bluntly: “If a man is guilty of a capital offense and is put to death, and you impale him on a stake, you must not let his corpse remain on the stake overnight, but must bury him the same day. For an impaled body is an affront to God: you shall not defile the land that the Lord your God is giving you to possess.” (See Dueteronomy 21:22-23; it is from this verse that we derive the rule of quick burial for everyone.) The Sages of blessed memory carried this much further, equating humiliation to pain and insisting that the method of execution itself had to be painless. They noted a verse in Proverbs (31:6), which states, “Give strong drink to the hapless and wine to the embittered.” This led Rav Chiya bar Rav Ashi to declare, “When one is lead out to execution, one is given a goblet of wine containing a grain of frankincense in order to numb his senses.” (See the Babylonian Talmud tractate Sanhedrin 43a.) Shortly thereafter (BT Sanhedrin 45a), there is reference to a debate regarding whether preventing the humiliation of a person about to be executed is in fact separate from the issue of pain and whether it actually takes precedence over causing pain during the execution. As part of this discussion, we are told: “Rav Nachman said in the name of Rabbah bar Avuha: When Scripture said ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’ [Leviticus 19:18], [it meant to teach us to] choose a ‘pleasant death’ for him.” The commentator Rashi explains that such “pleasant death” is necessary so as not to embarrass the condemned man (or woman; a woman’s dignity actually is at issue in this Gemara’s discussion and in one found in BT Arachin 7a). The question must be asked: Why should we care anything for the comfort or dignity of someone who committed a capital crime (especially a brutal murder or murders)? The answer is twofold: The simple answer is that the human body is made in God’s image and must be treated with dignity even if the possessor of that body did not deserve it. The complicated answer is: If causing pain or denying dignity makes the punisher feel better, is he or she—are we?—any better than the person being punished? ###