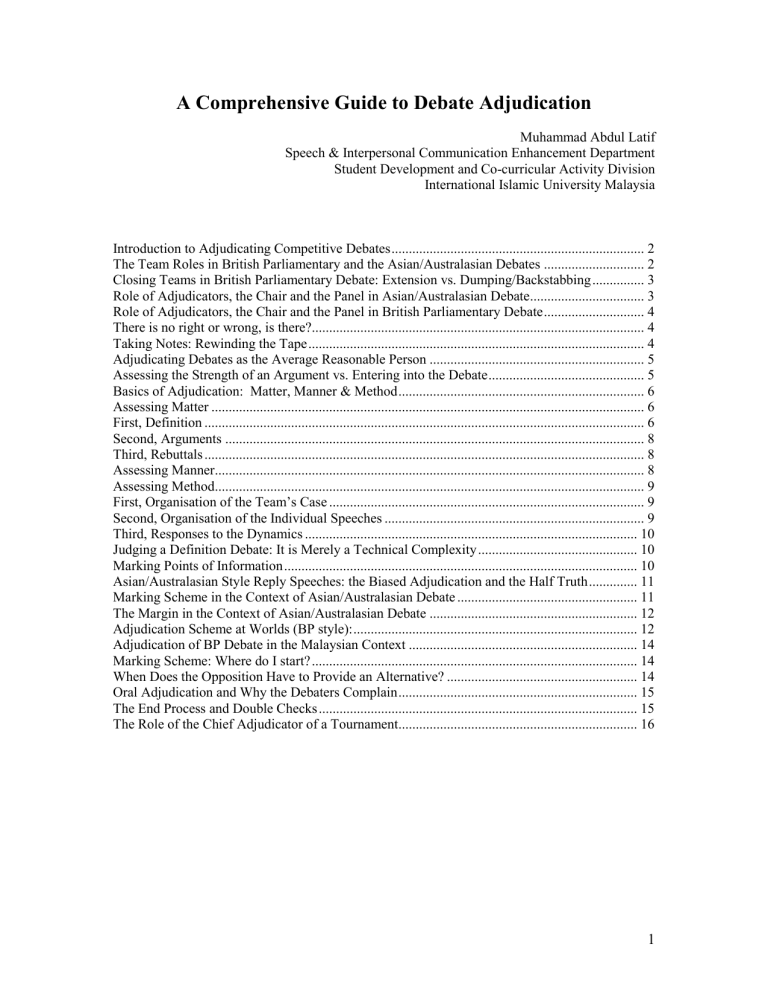

Guideline to Debate Adjudication - International Islamic University

A Comprehensive Guide to Debate Adjudication

Muhammad Abdul Latif

Speech & Interpersonal Communication Enhancement Department

Student Development and Co-curricular Activity Division

International Islamic University Malaysia

Closing Teams in British Parliamentary Debate: Extension vs. Dumping/Backstabbing ............... 3

1

(Note for the Participants of the Adjudicators’ Workshop at U.P.S.I: The Royal Malaysian

Intervarsity Debating Championship (known as Royals for short) uses the same format as that of the All Asian Intervarsity Debating Championship. Thus in this guide everything that is applicable for the Asian debating format is equally applicable to Royals. The discussion about the British Parliamentary Debating Format is not relevant for Royals. However, it is good to know about this format as it is the format for the World Universities Debating Championship and a number of English debating competitions in the country and the region use this format.)

Adjudicating debates is a subjective exercise. Unlike many sports, in debates there is no clear method of proving a team’s score. Adjudicators, quite often, are equally divided as to the winner of a debate, particularly in very close ones. This guide intends to minimize subjectivity in debate adjudication, clarify the defined rules of debate and bring consistency in the adjudication of

English debates in the country and in the region. This guide does not explain in detail what a debate is and the differences among various formats of debates, although it provides a basic introduction. As this focuses on adjudication of competitive debates, it is advisable that the reader has actually seen a competitive debate before reading this guide.

Introduction to Adjudicating Competitive Debates

There are many competitive debating championships following different formats/style of debating around the world and in the region. Among these formats, the Australasian, the Asian

Parliamentary and the British Parliamentary formats are the most well known in the region.

Although these formats differ in some areas, the skills to adjudicate these debates are very similar. Assessments of teams’ strengths and weaknesses, arguments, manner etc. follows more or less the same rules. When adjudicating competitions in different formats, the adjudicators need a good understanding of the rules of the different formats in addition to the general rules of assessment of a debate.

The Team Roles in British Parliamentary and the Asian/Australasian Debates

In the Australasian/Asian format of debates, there are two teams in the debate: the government and the opposition. The role of the Government team is to support the motion. This involves defining the motion, constructing a positive case in favour of the motion, providing substantive materials and arguments in support of the case and responding to any challenges made to that case by the Opposition. The role of the Opposition team is to negate the motion. This involves responding to the Government's definition, constructing a case in opposition to the motion, providing substantive materials and arguments in support of the case and responding to the arguments delivered by the Government.

In British parliamentary debates, there are four teams: two on each sides i.e. government and opposition. The teams are known as Opening Government, Closing Government, Opening

Opposition and Closing Opposition. The general roles of the government and opposition teams are the same as those in Asian/Australasian format. The two teams on the same side, although are different teams, must work as one bench supporting the same general idea. Since only one team

2

out of the four will eventually win the debate, the closing teams may and should distinguished themselves from their opening teams, in terms of focus and arguments.

Closing Teams in British Parliamentary Debate: Extension vs. Dumping/Backstabbing

The closing teams’ task is challenging in the sense that they have to support the opening teams but at the same time have to distinguish themselves from the opening teams and make their own impact in the debate. The closing teams should distinguish themselves by providing an extension and by brining original contributions in the debate while defending the opening team of the side.

An extension is new arguments, analysis, and applications that support and further strengthen the opening team’s case. A ‘mechanism’ or a ‘model’ can also be a legitimate extension provided a mechanism is important in the debate and the opening team did not provide one. It is also possible that a closing team comprehensively develops an argument or issue that was only mentioned in passing by the opening team. In this situation such a development can be treated as an original contribution and thus a legitimate extension.

A closing team should not contradict or be inconsistent with the opening team. If an opening team has presented a plainly weak case, it is the responsibility of the closing team to patch the holes and re-interpret the issues to make the case sound. A closing team cannot stab in the back or dump the opening team even though the case of the opening team has been very weak and torn apart by the opposing team. Defending a weak case of the opening team through refining, finetuning, re-interpreting and bringing additional analysis while roughly following the general line of argumentations of the opening team presents the best chance at wining for a closing team.

Adjudicators should not expect a closing team to defend what is indefensible. For example, contradictions within the case, factual errors, very illogical arguments etc. of the opening team need not be defended by the closing team. But in the process of choosing what to defend of the opening team and trying to, perhaps, shift the focus of the debate, the closing team should try not, to sound like they are abandoning the approach of the opening team. If there is a feeling among the adjudicators that the closing team has dumped or backstabbed the opening team, the adjudicators should consider ‘why the closing team dumped the opening team’, ‘was dumping absolutely necessary to ensure survival of the closing team’, ‘did dumping lead to a better debate’.

A closing team may depart from the opening team when there is a dispute of definitions between the opening teams and the opening opposition provides a valid redefinition. However, if the definition given by the opening government is a valid one, it is expected that the closing government defend that definition.

Role of Adjudicators, the Chair and the Panel in Asian/Australasian Debate

The three main roles of an adjudicator is to decide the winner, reason out the decision and provide constructive criticism for the teams. A single adjudicator or a panel adjudicates debates. In the case of a panel at the Asian/Australasian debates, the adjudicators decide the winner individually and fill up the score sheets and pass them to the chair. The chair opens all the score sheets only after he has filled up his. The winner is decided based on majority. After the winner has been decided, the chair generally conducts a discussion among the adjudicators regarding the strengths and weaknesses of the teams. No change of decision is allowed upon the discussion. The chair delivers the verdict, and in case the chair is in the minority, it is advisable that a member of the majority does so.

3

Role of Adjudicators, the Chair and the Panel in British Parliamentary Debate

As there are four teams in a British Parliamentary debate, adjudicators will rank the teams as 1

2 nd , 3 rd and 4 th st ,

. The ranking of the teams must be reflected in the teams’ total marks. Thus the team that ranks first must have more points in total than the team that ranks second. The total marks of two teams in the same debate cannot be the same, as the adjudicators have to put one of them at a higher rank than the other.

The ranking of teams is achieved through the discussion among the adjudicators in the panel. In this regard it differs from adjudicating an Australasian/Asian format of debate where adjudicators reach their verdict individually and the team that gets majority votes of the adjudicators in its favour is declared as the winner.

In British Parliamentary debates, I have observed two ways of conducting discussions among good adjudicators. First, where the adjudicators give a tentative ranking that they have individually reached and then they discuss to reach an agreement. The advantage of this method is that it ensures that adjudicators freely express their ranking without being influenced by other adjudicators’ opinions. However, this method may present some difficulty in terms of reaching an agreement as adjudicators whose initial ranking were different may not be very keen to change their ranking after discussion.

Second, where the adjudicators discuss the general features of the debate and strengths and weaknesses of each team. It is always easier to agree on strengths and weakness of the teams, and the important aspects of the debate, rather than the ranking of teams. Once agreement has been reached on these areas, it is then easier to reach an agreeable ranking.

When a unanimous agreement as to the ranking cannot be reached, the adjudicators may try to reach a majority decision. If a majority decision cannot be reached, the chair of the panel will have the final say in deciding the ranking. In this process of discussion and coming up with a ranking the chair of the panel acts as the moderator.

There is no right or wrong, is there?

Many of us will say, in debate adjudication there is no right or wrong decision. This is only partially right. Yes, there is no right or wrong when it comes to assessing the subjective elements of a close debate. But there are clear-cut rights and wrongs when it comes to the process of adjudication. It is obviously wrong if an adjudicator fails to listen to an idea of a team no matter how ill developed it may be. Nothing is right about not noting that a team has developed most of its substance in the last few minutes of the debate. The most important aspect of being right is to consider every single issue and remain methodologically correct in comparing the faults and strengths of the teams.

Taking Notes: Rewinding the Tape

Adjudicators should maintain detailed notes during the debate. Notes should be taken in such a way that a glance over the notes reminds the adjudicators as how every speech and the whole debate progressed. By looking at the notes, one should be able to rerun the debate in his/her mind.

4

I call it visualizing the debate once again after it is over. This is not to say that the adjudicators should take tens of pages of notes only to find that they never have the time to look at them before they have to decide, or never have the time to appreciate the beauty of the speech by looking at the debater and enjoy his/her presentation. But as I said, it should be enough to rerun the debate in your mind.

I found one practice very helpful and that is to make my own remarks at the end of every speech regarding the debater’s performance. Remarks like ‘reads too much from notes’, ‘did an excellent job in dealing with a particular issue e.g. fairness’, or ‘fails to address a particular issue e.g. fairness which is the main argument of the other team’ ‘the questions he /she raised that I expect the next debater to answer’, ‘the questions he/she failed to answer that were raised by the previous debater’. Before a speech, one may note down the issues or questions that one expects the debater to address. These are not issues that I think are important, rather these are issues that the previous debater has raised. These methods are every person’s own. I have seen lot of adjudicators using pens of different colours to take a special note of things they want to remember. These remarks, colouring etc provide an explanation behind the interim marks and help adjudicators rerun the debate when needed.

Adjudicating Debates as the Average Reasonable Person

The adjudicator enters the debate chamber as an ‘ average reasonable person’ . An average reasonable person is a fairly well-informed citizen of the globe with an average understanding of global and regional issues, and a basic understanding of popular disciplines and logic. The adjudicator must set aside his/her exceptional personal preferences, experiences, opinions or expert knowledge, which will not be shared by an average reasonable person. An adjudicator is supposed to be a jack-of-all-trades and master of none.

However the adjudicator is an expert in terms of the rules of debate. Adjudicators (often being ex debaters) tend to analyse the argument by pin pointing the possible weaknesses of it, as the opposing team would do it. This sometimes will be seen as ‘entering into the debate’ (discussed afterwards). Adjudicators must strictly avoid this. The adjudicators should merely determine whether the arguments are convincing in the eyes of an average reasonable person. An interesting observation in this respect is that an average reasonable person is more easily convinced than a debater, because he is open to be convinced. Generally an average reasonable person is equally easily convinced otherwise when the merits of the opposing side are pointed out. Adjudicators should avoid coming in between this process of the teams trying to convince the average reasonable person by bringing their own views of what is weak or what is strong unless it is obviously so.

Assessing the Strength of an Argument vs. Entering into the Debate

The most obvious instance of adjudicators entering into the debates is when adjudicators bring in their expert knowledge or preferences into the debate. They also enter into the debate if they build the arguments for the teams. Adjudicators should not supplement an unclear or ill developed argument with their additional explanation. However, the adjudicators’ task is to assess the argument’s strength. He should point out the weaknesses that an average reasonable person will observe. He should not go beyond that and assume the duty of finding faults on behalf of the opposing teams. In this case he can be seen as entering into the debate.

5

Take a very tricky example (real). The debate is about genetic engineering of crops. The government team argued that the third world does not have proper bodies that can regulate the growth of genetically engineered crops. The opposition team ignored the argument. The adjudicator in the verdict stated that he finds the argument not convincing because as an average reasonable person he would know that in third world countries there is the ministry of agriculture that can regulate. If this was to be raised by the opposing team, then the government team could have responded with the issue of ineffectiveness of and corruption in third world ministries. I also ponder whether the average reasonable person knows how efficient/ corrupt the third world ministries are. At the end, I concluded that in this debate the adjudicator has either entered the debate or has only considered half of the average reasonable person’s knowledge (that there is the ministry of agriculture, since the adjudicator ignored the fact of ineffectiveness of the third world ministries). In any case the adjudicator was methodologically wrong. The best practice in these cases will be to let the teams fight out what is right or more convincing and for the adjudicators not to bring issues unless the teams themselves pick it up. As I said the average reasonable person will not look for faults, but will mark one when it is made obvious.

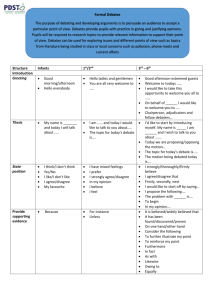

Basics of Adjudication: Matter, Manner & Method

Debates are generally judged on the basis of matter (40), manner (40) and method (20). In Worlds the categories are matter and manner while method is included within the two.

Assessing Matter

Matter includes: i) Definition

set up of the case, burden of proof etc. ii) Arguments

Key statement, explanation, analogy, examples, evidences etc. iii) Rebuttals

Key statement, explanation, analogy, examples, evidences etc.

-

The adjudicators should look at all these aspects of matter and give the appropriate score to the debater.

First, Definition

A summary of the rules of definition for is as follows: a) The definition should be reasonable: The definition should be reasonable and should state the issue or issues arising out of the motion to be debated, meaning of any terms in the motion requiring clarification and display clear and logical links to the wording and spirit of the motion. Thus a definition is unreasonable when it displays no clear link with the topic or it involves a misinterpretation of the words or the spirit of the motion. A definition is also unreasonable if it employs overly specific knowledge or runs counter to the resolution.

There must be a clear and logical link between the motion and the definition. For example, consider the motion “This house supports affirmative action”. The Government defines affirmative action to mean supporting a "disadvantaged" group. This group,

6

according to the Government, should not be limited to just humans. The Government then argues that in the animal world, some species are endangered and therefore can be considered "disadvantaged" because of their low numbers. A prime example of this are the whales which are hunted and killed by Japanese whalers. Then the context in which the Government set the debate is “that the UN should impose economic sanctions on

Japan for its whaling activity". To propose a definition that is only remotely linked to the motion such as this is called "squirelling" . This is strictly prohibited, and such definitions can be challenged by the Opposition.

The definition should not incorporate overly specific knowledge.

It is unreasonable if the

Government proposes a definition that includes topics which are outside that of the range of a typical well-read university student. In other words, the definition must be limited to topics which the Opposition can be reasonably expected to debate and must not depend on a detailed understanding of specific facts which may not be available to the general public.

The definition should not run counter to resolution. At times, due to lack of understanding of the topic or even intentionally, Government teams end up taking the Opposition’s case.

An example of such a definition is the motion that “Human rights is but a song and dance” where the Government defined the word “but” to mean “not” and started arguing that human rights is a serious thing and not a song and dance. The Opposition also argued in the same way that human rights are important. This definition is certainly against the spirit of the motion.

There could be other instances of unreasonableness of a definition. Thus the Government teams should not stretch the definition to an extent that a good majority of adjudicators find in unreasonable to some degree. By doing so the Government takes the risk of being challenged by the opposition and adjudicators giving low score to them for a bad definition. b) The definition must not be truistic or tautological.

A truistic definition is one which cannot be rationally opposed. If the Government were to define the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified" to mean that there is justification in one's killing of another person in self-defence when the latter is threatening his/her life, the

Opposition may successfully challenge the case as truistic. This is because no reasonable person can or should be expected to advocate otherwise. A tautological definition is one that proves itself by the very meaning and set up given to the topic. c) The definition must not employ time/place setting.

The Government may not set the time or place of the debate unfairly. However the Government can bring the debate to a well known issue which, in effect, narrows the debate down to a region or country to be the centre of the debate. In this case it will not be seen as an unreasonable place setting.

For example if the Government defines the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified" as military intervention in the Middle-East Conflict, the definition is fine. The criterion to judge a time/place set definition is that of an ‘average reasonable person’. The government can not narrow down the scope of the debate in terms of time and place in such a way that an ‘average reasonable person’ is not expected to know or be able to debate the motion as defined.

A good definition explains the key words of the topic, irons out the issues/contentions of the debate and identifies the burden of proof following the rules stated above.

7

Second, Arguments

An argument has a basic statement. Then it is followed by logical analysis and explanations as to why the basic statement stands. Evidences are adduced to substantiate the analysis. An argument is often concluded by linking back to the burden of proof or the basic contention under the topic.

The adjudicators should assess whether the arguments were developed sufficiently to meet the above requirements. Questions that adjudicators generally ask are: did the debater discharge his burden of proof, did the arguments logically prove his contention, did he demonstrate good understanding of the major issues and relate smaller points to them, etc?

The adjudicators should assess the strength of an argument regardless of whether the opposing team addresses it or not. A weak argument is a weak argument irrespective of whether the other team points it out or not. However, if an important argument of a team is plainly weak, an opposing team is equally guilty, if not more, if they do not address it. To me the opposing team is even more to be blamed for letting the team get away with a weak argument. If the opposing team points out that an argument is weak, the team has an opportunity to defend, but if the adjudicator says so, they have no chance to defend. Therefore, the adjudicators should treat an argument as weak only when it is plainly weak to an average reasonable person. The adjudicators, at the same time, should equally fault the opposing team on at least method (may include matter as well) for not addressing it.

Third, Rebuttals

The rebuttals are similar to arguments. Arguments are to prove a claim whereas rebuttals are to disprove the validity of that argument or claim. Thus good rebuttals will also, generally, have a basic statement, explanation, analysis and supporting evidences. A team does not have to rebut each and every example introduced by the other team. Instead they should rebut the fundamental logic of the argument or the case and raise possible objections to the proposal (if any).

Assessing Manner

Following are elements of manner: respectable attitude towards the judges and the other team, vocal style: volume, clarity, pace, intonation etc, appropriate use of notes, eye contact, body language, hand gestures, impression of sincerity, humour, wit, appropriate sarcasm.

Assessing manner is very subjective. Some adjudicators like aggressive debaters, while many others like the calm ones. One important thing that adjudicators should remember is that there is no one best way to debate; there is no difference between an aggressive and forceful debater and one who is calm and understated if both are able to demonstrate the ability to persuade and hold the attention of the adjudicators. Notwithstanding this, there is however a limit to the degree of acceptable "manner" - neither an overly aggressive nor a too understated debater will score many points. Dress is not part of manner (to the surprise of the many traditional adjudicators!). The debaters should not be racist, sexist or plainly offensive to person, or make derogatory remarks about other debaters in the debate. These are also instances of bad manner.

8

The fundamental questions that decide the manner score, generally, are: ‘is the speech persuasive’, ‘is he/she able to maintain the audience’s attention’, ‘is his/her speech clear’ and perhaps many others.

Assessing Method

Method consists of three elements: a) organisation of the team’s case, b) organisation of individual speeches, c) responses of the team to the dynamics of the debate.

First, Organisation of the Team’s Case

To assess team method the adjudicators consider whether the team’s overall organization of arguments is effective to prove the case in contention. The adjudicators should also look at the continuity of the team’s theme in all speeches, consistency among all debaters (no contradictions), reinforcement of team members' arguments, clear & logical separation between arguments.

I have seen many teams, even good ones, developing the substantial materials late in the debate.

These materials are sometimes introduced only by passing in earlier speeches and then the third speaker develops so substantially that it sounds like a very strong argument at the end. Some teams do it as a strategy (!). It is a sneaky way of trying to win a debate. The adjudicators must be careful about these instances. It also happens that many of the substantial arguments of the government team are only rebutted in the 3 rd negative speech. It is completely unacceptable. The team should not only suffer considerably in method marks, but earlier speeches of this team should also suffer matter marks as they did not address substantial matter introduced in the debate during their speeches.

The best team strategy is to put the best arguments on the table at the very beginning of the debate and not even leave them to the 2 nd speaker. Similarly the opposition team should start addressing them head on from the very first speech. A debate should have strong clashes right from the first speech of the opposition. A good example of such a debate is the Grand Final of

Worlds 94 (There are many others, but this is perhaps one which is easily available on tape).

Second, Organisation of the Individual Speeches

A model individual speech will have the following elements: a) Statements regarding definition/ theme/ burden of proof / quick overview, b) Rebuttals: rebuttals of the arguments as well as rebuttals of the rebuttals, c) Presentation of arguments, and c) concluding summary. These elements in general should be present in all the speeches. However, some specific speeches will have some differing elements. For example, the Prime Minister will spend substantial amount of time (2 to 3 minutes) setting up the definition which no other speaker will do unless the definition is challenged. Similarly the whip speakers, i.e. third speakers in Asians/Australs and fourth speaker in British Parliamentary debates, will not present any new argument and will spend substantial amount of time on rebuttals. Reply speakers will bring an overall comparison showing the strength of the arguments of one team over the other. There is no reply speech in British

Parliamentary debates, thus the reply speakers’ role is generally accommodated within the whip speeches.

9

Individual structure should be assessed in terms of whether the speaker performs the role expected of him/her effectively. Adjudicators will also look at time management in the speech.

Third, Responses to the Dynamics

Debates do not always progress the way teams thought it would before they entered the debate.

At every point in the debate, some issues become of prime focus and the core of the debate and some other issues initially thought of being contentious become irrelevant or out of contention.

Some times teams concede to some of the issues and thus it does not make sense for the other team to spend time developing them. Debaters should understand these progresses and dynamics and respond accordingly and not just go ahead and speak as they planned during their preparation time.

If a debater ignores the most important arguments of the earlier speaker and does not rebut them he lacks dynamics and should thus score low in method, even though he rebuts the minor arguments of the other side. It is possible that the debater understands the issues well and addresses them but his/her responses are weak. In this case he gets good score for method for understanding the dynamics of the debate but scores low in matter for unconvincing responses or arguments.

Judging a Definition Debate: It is Merely a Technical Complexity

A definition debate is not necessarily difficult to decide, if you are aware of the definitional rules.

In a definition debate the adjudicators should first consider whether the definition provided by the government passes the rules. If it does, the conclusion is that the challenge made by the opposition is unjustified. If the opposition leader cannot justify the challenge he has already lost the debate on one count. But this alone will not settle the whole debate; the adjudicators still have to look at the developments that take place after that. Adjudicators have to consider how both teams argue out the case under each definition, or argue out the validity or otherwise of the definitions. Adjudicators will also consider the ‘even ifs’ introduced by both teams when required and matter, manner method of teams as a whole. Thus it is not merely who wins the issue of definitional challenge that automatically decides the debate. Adjudicating a definition debate requires a careful analysis of the definitional rule and the technical roles performed by all debaters of both the teams.

Marking Points of Information

The debaters are advised to take at least two POIs during their speeches. All debaters are advised to attempt to give POIs but they should not do so in a manner disruptive to the debater holding the floor. What amounts to be disruptive is subjective. However two clear examples are when a debater uses long and loud sentences just to get the attention towards his/her attempt to give POIs

(I have seen it happen) or say if a debater stands up on a POI within few seconds after he has been rejected. A 20 seconds waiting period before one stands up again is the rule of the thumb

POIs are assessed on the basis of the threat they pose to the strength of the argument of the debater and the value of its wit and humour. But the responses to the POIs are judged on the basis of its logical and intellectual strength, promptness and confidence in answering, and value of its wit and humour.

10

Marks for the POIs and responses to POIs should be incorporated within the marks of the speech in various categories. For example if a debater is inactive in giving POIs he may score less in method. Again if a debater gives a brilliant POI that kills an argument instantly, he could be given additional matter marks for that.

It is relatively easy to mark the responses to POIs as the responses are made within the speech and when it is being marked, whereas it is rather difficult to mark the POIs. Because POIs are offered before or after the speech is marked. It is advisable that the adjudicators look at the separate note they keep regarding POIs and add into or deduct from their speech score as appropriate to reflect their offerings of POIs. For example if a debater offers very good POIs after his/her speech is already marked, his/her mark can be increased to reflect his/her activism in

POIs. On the other hand if a debater does not offer POIs or offers bad ones marks can be deducted from his/her speech score. At the end, all the debaters’ score will not only reflect how they performed in their speeches but also their POIs throughout the debate.

Asian/Australasian Style Reply Speeches: the Biased Adjudication and the Half Truth

Reply speeches are marked out of 50 (matter 20, manner 20, method 10). It is easy to score a reply out of 100 and then divide by 2. A good reply speech is often a biased adjudication. A good reply speech is the one that summarises the major contentions of both the teams and provides a summary of argumentation that took place during the course of the debate proving that one team has substantial edge over the other. It incorporates the arguments and rebuttals of both the teams in deducing a conclusive position.

Adjudicators should be careful regarding reply speeches as obviously a team, which is losing the debate in some areas of contention, may and will choose to down play or not even mention that those areas of contention exist. This is why one reply speech on its own is only half the truth.

Adjudicators should not be too naïve into believing that those were the only contentions, even though the other team fails to point out areas of contentions where they have an advantage.

However, two reply speeches properly done should bring about the whole truth to the adjudicators.

Marking Scheme in the Context of Asian/Australasian Debate

Each substantive speech is marked out of 100 according to a detailed division as follows and the reply speech is marked proportionately out of 50.

Matter

Manner

Method

Over all

Total

40

40

20

100

Min-Max

27-33

27-33

13-17

67-83

Av.

30

30

15

75

The score for an average speech is 75. The minimum for a debater is 67 and the maximum is 83.

These ranges of average, minimum and maximum vary depending on the competition in context

(Of course, marking scheme for Worlds is entirely different). What is an average speech is very difficult to state. But I will safely say it is a speech that fulfils the technical role of the debater, addresses the major issues at hand to the satisfaction of an average reasonable person and is

11

delivered with a clear style of presentation. It may help the adjudicators if I mention here that during the last few Asians the score of the Top Ten debaters of the tournaments have been around

76.5 to 78. If we agree to take that as a standard to be followed giving a debater 77 inevitably means that that speech is among the ten best speeches in that round. Other information from the table above are clear. A speech should never go above 83 or below 67. I have rarely seen a debater in Asians scoring 80 or above (Not that these tournaments do not have great debaters, rather they have strictly regulated adjudication standards). Thus when I give a speaker 78, I expect to see him in the Grand Final. A score 76 or 77 will mean a quarter or semi finalist’s quality of speech.

The Margin in the Context of Asian/Australasian Debate

Margin is the difference of the total score of the two teams. All Asians categorises the win/loss of teams into three categories: close, clear and thrashing. A description of these categories and the range of points within these categories are as follows:

Category Points Description

Close/

Marginal

Clear

0.5-4

5-8

A very close debate; only minor differences separating the two teams.

A relatively clear decision, with one team having an obvious advantage.

Thrashing 9-12 A very clear win, with the losing team failing on one or more fundamental aspects of the debate.

Margin reflects a comparison of the two teams in the debate. Whereas the speakers’ score reflect both a relative comparison of the team’s speakers as well as an absolute assessment of the speakers vis-à-vis expected standard in the competition.

It is perfectly possible to come up with a margin of lot more than 12 despite marking the speeches within the range of 67-83. At the end of the debate the adjudicator should decide how much margin is suitable for the debate then adjust the speaker’s score accordingly. To adjust margin it is advisable that the adjudicators bring the low scoring team up instead of bringing the high scoring team down. This avoids victimising the excellent debaters meeting a weak team. But of course a compromise can be drawn when appropriate.

Adjudication Scheme at Worlds (BP style): i) Method as a Subset of Manner: In the world debate format each speech is marked out of 100 of which 50 is for matter and 50 for manner. Method is considered within manner. For example proper organisation of speech can be seen as part of the manner. Method is as important as in any other formats of debates because proper methods make the team/speech highly effective in persuading. However, when it comes to marking it is not a separate category for marks like that in Asians/ Austals. ii) Team Grades and Marks: Each team in the debate is to be given a letter grade between A-E. This grade will be based on the performance of the team as a whole. A team may be graded ‘A’ although one of the debaters individually is graded ‘B’.

12

Following are the grades, marking range for the grades and their meaning (source:

World Parliamentary Debating Rules by Ray D’Cruz):

Grade Marks Meaning

A 180-200 Excellent to flawless. The standard you would expect to see from a team at the Semi Final / Grand Final level of the tournament. The team has many strengths and few, if any, weaknesses.

B 160-179 Above average to very good. The standard you would expect to see from a team at the finals level or in contention to make to the finals. The team has clear strengths and some minor weaknesses.

C

D

E

140-159 Average. The team has strengths and weaknesses in roughly equal proportions.

120-139 Poor to below average. The team has clear problems and some minor strengths.

100-119 Very poor. The team has fundamental weaknesses and few, if any, strengths. iii) Individual Debater Grades and Marks: Each individual debater is also graded and marked using a similar scheme. As mentioned earlier even though a team may be graded ‘A’, an individual member of the team may be given ‘B’ grade. However the total of the two members must reflect the correct grade and marks of the team as a whole. Following are the grades, range of marks for the grades and their meaning:

Grade Marks Meaning

A 90-100 Excellent to flawless. The standard of speech you would expect to see from a speaker at the Semi Final / Grand Final level of the tournament. This speaker has many strengths and few, if any, weaknesses.

B 80-89 Above average to very good. The standard you would expect to see from a speaker at the finals level or in contention to make to the finals. This speaker has clear strengths and some minor weaknesses.

C

D

E

70-79 Average. The speaker has strengths and weaknesses and roughly equal proportions.

60-69 Poor to below average. The speaker has clear problems and some minor strengths.

50-59 Very poor. This speaker has fundamental weaknesses and few, if any, strengths.

13

Adjudication of BP Debate in the Malaysian Context

One interesting point to note is that the marking range for individual speeches at Worlds is 50-

100 whereas at Asians/Australs is 67-83. At Worlds a wide range is needed considering the number of teams and disparity in their performances. Do we need such a wide range at BP debate tournaments in Malaysia? I believe not. Firstly, at the Malaysian tournaments the disparity of performance of the debaters is nowhere as big as that at the worlds. Secondly, having such a wide range will unnecessarily increase the elements of subjectivity. The Malaysian BP debate tournaments like the NVD and others have generally adopted the marking scheme of the Asians/

Australs that is each individual speech is to be marked within 67-83 following the criteria of three

M’s. By adopting this marking range, requirement of letter grades (A-E), perhaps prudently, has been omitted from most of these tournaments. Thus the adjudicators in these tournaments are supposed to rank the teams and provide the marks for each debater as per range (67-83).

Marking Scheme: Where do I start?

I apply a simple method for marking speeches during a debate. I am stating it here for the benefit of those who would like to try it out. First give a score the Prime Minister based on the above explanation of minimum, maximum and average. His score will strongly draw upon the overall expectation from the whole tournament. Then compare all other speeches using the Prime

Minister’s speech as the benchmark. A comparison also should be made among all the speeches so that all the speakers get a score that they deserve not only in comparison with the Prime

Minister but also in comparison with each other.

In my experience with lot of new adjudicators, I have found that when they assess a speaker better than another, they immediately give the better speaker a score substantially higher (2/3 points) than the earlier one. In this situation the difference of score between the two teams might go beyond the margin limit (discussed later). It is advisable to give both the speakers the same score if you are not sure which one is better. And when you are confident that one is better than the other the difference of score among them should not be a huge one, unless it has to be.

When Does the Opposition Have to Provide an Alternative?

Many times I have been asked this question, ‘the opposition only criticised the government and never provided an alternative, is that enough for them to win the debate?’ The answer depends on the topic and progression of the debate. When the debate involves a proposal by the government team to solve certain problem/issues that both teams acknowledge, the opposition has, beside criticising the government’s proposal, the option of providing an alternative. If the opposition chooses to provide alternative, the debate will be mostly about the comparison of the two proposals. Whereas, if the opposition choose only to criticise the government’s proposal and not give an alternative, the following issues should be considered to determine the responsibilities of both the teams:

1)

The government team’s burden was to propose a solution to a problem and therefore for them to win they must prove that their proposal will solve the problem or at least improve the situation,

14

2) By not providing a better alternative, the opposition chooses their burden to be that the government’s proposal will not solve the problem or improve the condition or that the government’s proposal has other dangerous implications and thus should not be accepted.

3) Sometimes the opposition may end up, impliedly, defending the status quo by arguing that by adopting the government’s proposal the situation will be worse.

Thus it is very much possible that an opposition very rightly opposes a model without giving an alternative model of its own. At the end the adjudicators should decide based on the burden of proof under the topic and how the teams have discharged that. If the opposition has successfully negated the government’s proposal without providing an alternative they may still win the debate.

Oral Adjudication and Why the Debaters Complain

Reaching the right verdict is one thing and delivering the verdict in a convincing manner is yet another. I have found, particularly in the context of the Asians, many adjudicators reach the right verdict with perfectly right reasoning, but not able to express their verdict like many others due to language difficulty. I would many times get them to adjudicate important rounds but not make them chair or put them in a position where they have to deliver the adjudication. This is to maintain the confidence of the debaters in the adjudicators’ pool.

In delivering the oral adjudication do not replay the whole debate; teams already know what they have said. Explain the main reason behind the decision. Most of the time the losing team is more interested to know why they lost, than the winning team trying out find out why they won. I prefer to focus on the losing team’s weaknesses and complement the decision with some of the strength of the winning team. ‘To win this debate, given the way the debate progressed, the government/ opposition needed to do … However they failed to …’ is a phrase that I often use in explaining verdicts.

Adjudicators may also highlight the differences between the two teams in terms of strength and weaknesses of the cases, technical strengths and weaknesses or differences in matter, manner and method.

Many times teams complain not because they disagree with the verdict, rather they do not agree with the reasons. Therefore adjudicators should be very careful in giving their reasons for the decision. For example pointing out more weaknesses of the winning team than the losing team will give a wrong impression. An adjudicator should never say that team ‘A’ did not reply to this argument introduced by team ‘B’, unless he is very sure that they actually did not give any reply.

It will be upsetting for the team if they actually gave a reply to that argument even though it could be very short and insufficient. The teams are generally happy if they see that adjudicators actually paid attention to everything that they have said but it was just not enough for them to win the debate instead of them feeling that they said many things but the adjudicator did not understand or did not pay attention to it.

The End Process and Double Checks

Occasionally, adjudicators come up to situation where they think team ‘A’ has won but when they calculate all the marks it is another team that has higher. You have to reconcile. Perhaps the interim marks do not reflect upon the whole debate and it can and should be adjusted if your end

15

impression is different. But one must be careful about changing the interims marks and make sure that the end impression is not just the impression from the last one or two speeches as they are still fresh in mind. Thus adjudicators need to go through the notes and make a thorough reconsideration in the light of the whole debate to reassign the marks. The bottom line is you should not just add up the interim score and make the decision.

In my adjudication practice, after the end of the debate, I make a summary of contentions, counter contentions, rebuttals, strengths and weaknesses in manner, method and POIs for both/all the teams. It allows me to have a clear over view all aspects of the team and it makes sure that I have not ignored anything that should be noted. This summary of each team becomes a useful notes for oral adjudication.

Before finalizing the decision, adjudicators should always double check the winner, margin, individual scores and total, and more importantly run through the notes to make sure they have no oversight of an issue and that they have considered each and every issue in the debate.

The Role of the Chief Adjudicator of a Tournament

Every tournament has a Chief Adjudicator (CA) assisted by 1-3 Deputy Chief Adjudicators

(DCA). The CA is responsible to prepare the debate topics, to oversee the draw allocation, to allocate adjudicators for debates and entertain any complaints on adjudication. The CA is in charge of conducting the training and test for adjudicators in the tournament leading to an objective assessment of the adjudicators skills and experience. This allows the CA to most efficiently allocate the adjudicators during the tournament. The CA should keep in mind the following when performing his/her roles:

An adjudicator should not adjudicate the same team more than once unless otherwise needed.

Adjudicators should define their conflicts during registration. Two kinds of conflicts should be taken into account: i) No adjudicator should be assigned to adjudicate teams from his/her own university, ii) No adjudicator should be assigned to adjudicate teams that are within their conflict of interest (e.g. any biological, emotional relationship with a member of the team etc.)

For the preliminary rounds, single qualified adjudicators are preferable over a panel of inexperienced adjudicators. This should be practiced particularly in the earlier rounds when the assessment of adjudicators is not fully clear. As the rounds progress the CA should have more panels and minimize single adjudicators.

Diversity in the Panels should be sought when possible. Panels should be fairly diverse in terms of their gender, nationality etc. Two adjudicators form the same institution in one panel should also be avoided where possible.

Complaints are not encouraged, but if there is any the CA should not allocate the same adjudicator to judge the team again irrespective of the validity of the complaint. This is because the organizer should give everybody the best possible professional treatment they can afford.

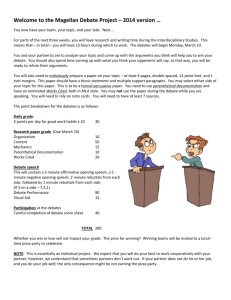

16